Today's episode, #380, is very special to me for a number of reasons. For one, it's part of the #RootCauseRacism series that Deondra Wardelle has organized on my blog this week. Secondly, I'm joined by Dr. Randal Pinkett and Dr. Jeffrey Robinson to talk about important issues of race, diversity, and equity in organizations. Together, they are co-authors of the book Black Faces in White Places: 10 Game-Changing Strategies to Achieve Success and Find Greatness and the upcoming book (2021) Black Faces in High Places.

Randal Pinkett, Ph.D. is an entrepreneur, speaker, author, and community servant. Randal is the co-founder, Chairman and CEO of his fifth venture, BCT Partners, a multimillion dollar management, technology and policy consulting firm in Newark, NJ, a partner in Blackwell-BCT, a joint venture with Blackwell Consulting Services, and spokesperson for the Minority Information Technology Consortium. He is a Rhodes Scholar and former college athlete who holds five academic degrees from Rutgers, Oxford and MIT (including the Leaders for Global Operations program). He was also famously the first and only black winner of “The Apprentice,” something we will talk about today.

Jeffrey A. Robinson, Ph.D. is an award winning business school professor, international speaker and entrepreneur. Since 2008, he has been a leading faculty member at Rutgers Business School where he is an assistant professor of management and entrepreneurship and the founding Assistant Director of The Center for Urban Entrepreneurship & Economic Development. The Center is a unique interdisciplinary venue for innovative thinking and research on entrepreneurial activity and economic development in urban environments. He has an MS in Civil Engineering Management from Georgia Tech University and a Ph.D. in Management from Columbia University.

In the episode, we talk about workplace issues related to diversity and inclusion. Should we aspire to a “color blind” world or do we need to recognize and celebrate color? What can we do to turn “white places” into more inclusive places for all? How can the “innovation economy” be made more inclusive, and why is that important?

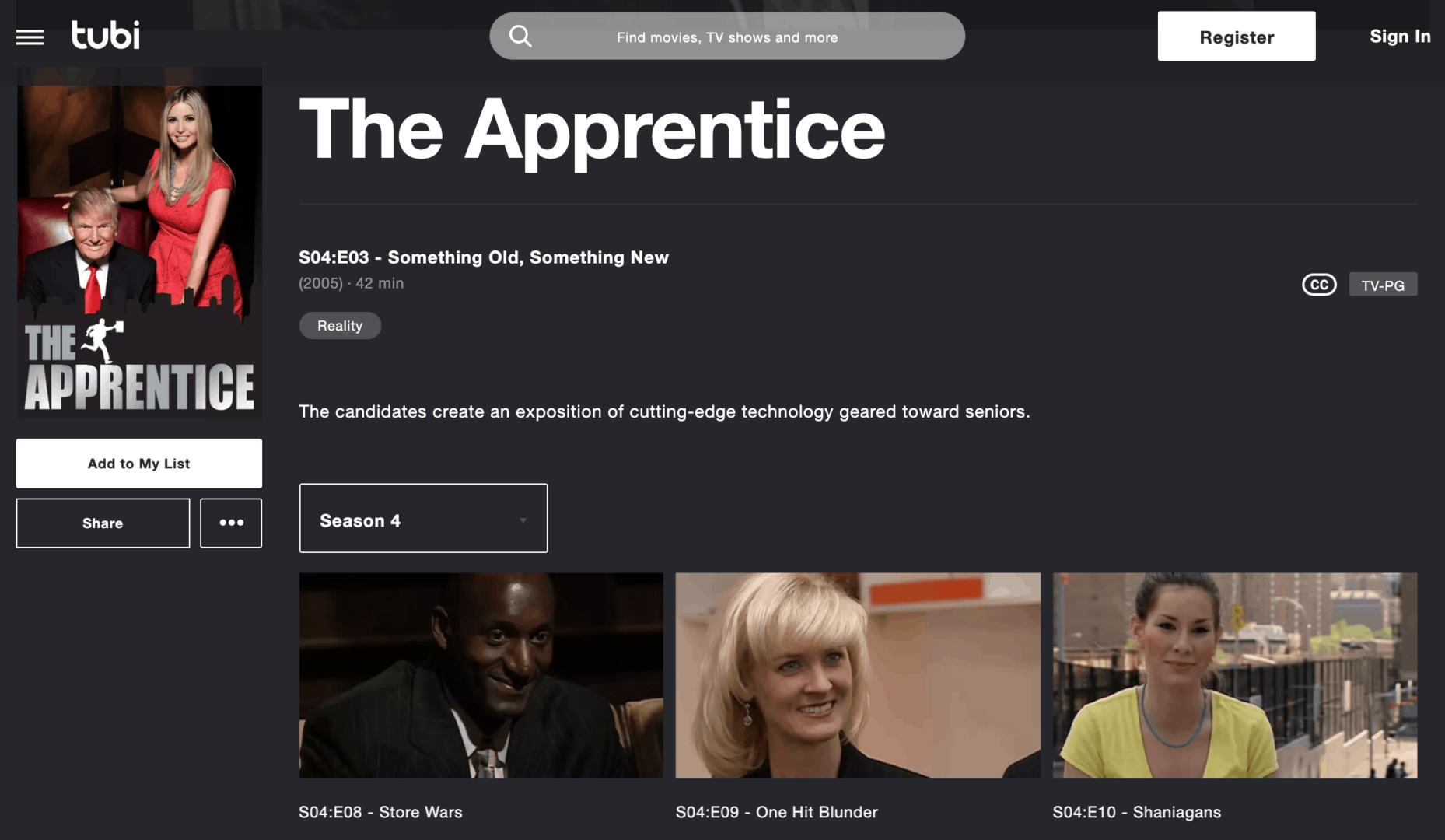

You'll also hear Randal talk about recently re-watching his season of The Apprentice online with his daughter. You can watch a separate 8-minute clip (an excerpt from the full interview) if you are particularly interested in his reflections about winning and being asked to share his win with the runner up. What did Randal learn while working in the Trump Organization?

I hope you enjoy the conversation, whether you listen or watch (or read the transcript below).

Streaming Audio Player:

Video Podcast:

Here is the section where we discuss The Apprentice in an 8-minute excerpt:

For a link to this episode, refer people to www.leanblog.org/380.

Topics and Questions:

- Is American “color blind?” Do you desire a color blind world?

- What's your reaction when white people say “I don't see color”?

- Why is it problematic when organizations recruit and hire based on “cultural fit” in Silicon Valley or elsewhere?

- Thinking of the title… “Black faces in White Places,” please share a story about being “a company's Jackie Robinson” and why that's a difficult burden to bear, as you say.

- Can you talk about the pressure to fit in to the predominant culture versus the need to stay true to your own identity?

- What does it mean to be “color brave” instead of color blind?

- Why is it important to call out and celebrate instances of “the first Black person to __________” or “the first Black woman to _________” in headlines and on LinkedIn?

- What advice would you have for white people to hep turn “white places” into more inclusive places?

- Randal — you were, quite famously, the first (and only) Black winner of The Apprentice. Why were you treated differently, being asked to share your title with the runner up, Rebecca Jarvis, a white woman?

Transcript:

Mark Graban: Again, we are joined today by Dr. Randal Pinkett and Dr. Jeffrey Robinson. Thank you both so much for being here.

Dr. Randal Pinkett: Thank you, Mark.

Dr. Jeffrey Robinson: Thanks for having us.

Mark: We have a lot I'd like to explore today. The two of you, of course, as the authors of your book, Black Faces in White Places. I was wondering at first if I can ask each of you to explore a little bit, question around — as you discussed in the book — is America colorblind? I find a lot of people particularly white people like to say things like, “I don't see color.” Is America colorblind at this point?

Dr. Pinkett: I'll take the first swing at the plate here and say that America is absolutely not colorblind.

Let's be unequivocally clear, it is not.

The issue is that many people are duped into believing that color blindness is somehow aspirational.

As if that's where they should aspire to be or if they've arrived there, that they're in a good place and now they need not go anywhere else. Whereas, we would argue that not only do we want you to see color because of its beauty, because of the diversity, because of the celebration of color.

We don't want you to also fall victim to the ancillary conclusions one might draw, if you really believe color blindness is the goal. You mean, you might believe that the workplace is a meritocracy. That everyone is treated fairly, that we only hire the best and brightest, that everyone has equal opportunity to succeed.

Then I ask you to look at the data. The data will tell you that at managerial levels, executive levels, C-suite boards, African Americans are grossly underrepresented, which means somebody is seeing color, because people are being denied opportunity based on their color.

Whether that is explicit that you are intentionally discriminatory or prejudice and the like or implicit, meaning it is your well intention, but your actions belie your intentions and the impact is otherwise. Either way, the end result is the same.

Mark: Jeff?

Dr. Robinson: I'd only add one or two things to that. I mean, every research study that looks into these things just shows the preponderance of evidence, as the lawyers like to say that there is bias in many different systems. I mean, all institutions.

Of course, we've focused a lot of our work on the business world, and thinking about how the business world is impacted by these implicitus. Not implicitus, I'm like explicit bias. There's a real strength in diversity.

To be colorblind doesn't allow us as a society to appreciate and respect the peoples who are coming to the table.

Then there's an authenticity we can all bring when we know that our diversity is a strength.

Mark: When you mentioned look at the data and you look at outcomes, which are measurable, undeniable, the question then traces back to the causes of inequity in outcomes. What are your thoughts on organizations today?

Has explicit bias been pushed underneath the surface and replaced with more implicit bias in terms of people have learned not to say overtly racist things? Does that then lead to a more hidden or insidious form of bias?

Dr. Robinson: It certainly can. The classic examples are in recruiting. You're talking about who you're going to hire. There's been several studies that have just done the name associations.

Biases that come straight out of what our impressions or our thoughts are about a particular person's name. “Oh, that person must be of that ethnic background.” Then what happens in the back of the person's mind is, “Oh, is that somebody I want to work with? Maybe not.”

Again, the other evidence is that where people live. We often live in very segregated neighborhoods — or said differently — we live in neighborhoods with people just like us. Whatever, just like us is? Whatever that means to you?

You bring to the table some of these biases when we look at resumes, when we are recruiting, where we go to recruit, how we ask questions, how we interact with people in terms of microaggressions. All of that factors into it.

A lot of the work that Randal and I and others are doing is to try to re-engineer that for companies, help them to see those biases and to uncover them, because they just reinforce that, what we have set in society.

These are not patterns you want to replicate, but then we see them and we continue to see it, and then we see tragic things that happen, like on George Floyd and other things. These are the kinds of insidious patterns we're trying to break.

Mark: Randal, you were nodding pretty vigorously. What would you like to add?

Dr. Pinkett: Nothing to add. I think Jeff spoke perfectly to the question.

Mark: As a follow-up, you talk about recruiting. It's similar to some companies in, let's say for example, Silicon Valley, have come to realize that the idea of hiring for what they would call cultural fit ends up being a really bad idea for different reasons in terms of hiring people who are like you, people who come from the same background as you.

Can either of you talk about that dynamic, and why it's important for companies to try to break some of that cycle, or how they can go about that?

Dr. Pinkett: Yeah, there's a social psychological principle called homophily, and homophily is the idea that we are naturally drawn to people who are like us. It's human. It's natural.

There's not anything necessarily wrong with that tendency. You think of the old adage, birds of a feather flock together, but it does become problematic when we have an inability to connect with people who aren't like us. That's when it becomes problematic.

In corporations, and we've seen this in our work at BCT, certain departments, certain roles, certain functions, certain levels begin to get stereotyped for people with certain profiles, certain schools, certain ethnicities, certain genders. You can get into engineering, versus executive suite, versus managers, versus finance.

The list goes on, and how we can get caught in these patterns of association, of who is a good, to your point, Mark, which I thought is a good one, who is the right cultural fit. Very subjective, very easy to overlook those who traditionally may not fit the stereotype.

That's why we advocate more formal measures of ensuring that there's diversity of perspective, and diversity of who's being considered.

We talk about diverse panels for interviews, that you have people who can look at candidates from different angles, different perspectives, but also having diverse panels of who's being interviewed, so that we can ensure that no one is being overlooked and no one is falling victim to what can be akin to groupthink when we think of who's qualified and who's not.

Mark: In the book, Black Faces in White Places, one thing that struck me, as a white face, is the privilege if not the luxury of thinking of places. It's very rare, I am thinking of professional circumstances when I have been the only white face in the room.

In the book, you talk about the burden of being a company's Jackie Robinson, the first black person in a certain role, or first black person in the organization. Can maybe each of you share a story about that to help us understand that perspective?

Dr. Robinson: To be the only one or the first one, I can think of several situations where in 2020, the Wharton School of Business has its first woman as dean, who's also an African American, also the first African American. It's 2020. [laughs]

There are certainly other schools in the upper echelon and business schools that haven't even achieved that yet, and 2020, they're the first person.

I know Dr. Erika James very well, and I know the interesting thing about who she is and what she's able to accomplish. I know she's a fantastic candidate. This is not her first deanship.

I also know that when we talk to people who have been in these similar situations and we reflect on our own experience we think about these four dimensions of people we call the “black faces in white places” experience.

Some of it has to do with your identity, the, “Who am I in this situation, and how do I position myself?” It's about meritocracy. It's wondering the question, “Are people looking at me, and are they going to give me the benefit of the doubt like they would everybody else, or are they going to give me and judge me on my merits?”

It's about this colorblindness we were talking about before, whether society or the people you're interacting with is going to be colorblind, or are they going to be really color-brave, to steal a phrase from Mellody Hobson.

Then, there's opportunity, “Where are my opportunities? Do I have the same opportunities as everybody else?” It's an interesting dynamic where you are thinking about these things and maybe not even articulating them, but you're thinking about it. While you're doing that, you're also trying to achieve the goals you have for your professional life.

It's a lot of work, a lot of mental work that goes on often to be the first one or the one of a few in a situation like that.

Dr. Pinkett: I may tell a story other than my own, because I think it's actually more powerful than my own, but I will say that part of the impetus for the book Black Faces in White Places was that Jeffrey's experience and my experience is that we've been black faces in white places for the majority of our lives.

Growing up in predominantly white neighborhoods, going to predominantly white public schools. Going to Rutgers University, we were a handful of African Americans in the engineering school, and then for him, Columbia, Georgia Tech for me, MIT, Oxford, the list goes on.

I remember when Jeff and I were involved with the National Society of Black Engineers, Jeff ran the national convention and one of the speakers we brought in was Dr. Mae Jemison, who was the first African American woman to go into outer space, also an engineer.

She told the story about how when she was young, she would tell people that she had this dream of going into outer space, and they would tell her,

“What makes you think that they're going to let a brown girl go into outer space?”

The beauty of her story was, getting back to this idea of being modern-day Jackie Robinsons, was that she never listened to the naysayers. That's the flip-side of being underrepresented, is that you may not see examples or role models who have blazed the trail, and so you're it. [laughs] You're the one to set the example.

While that's challenging, it also in some ways is very empowering, because it allows others to be inspired. I know her remarks that day inspired me to say, “Well, if that brown girl from the '60s could go into outer space in the '80s, then I need to make sure I step up my game for the '90s into the new millennium.”

Mark: Jeff, could you elaborate a little bit more on, you used the phrase color-brave, and help contrast that to being colorblind?

Dr. Robinson: Yeah. Mellody Hobson from Ariel Capital made this phrase in a TED Talk that she was talking about, and she pointed out what you did earlier, which is, to be colorblind doesn't help the situation. That just ignores what's out there, and it ignores a lot of things.

To be color-brave has to do with thinking about how all of these colors could come together, valuing the tapestry, the rainbow, whatever metaphor you want to use and fit in there, but it is how you will acknowledge and respect and engage with the wonderful colors that are in front of you.

Randal talks about this one a lot. Maybe he should add some more to that.

Dr. Pinkett: It's an inspiring TED Talk. I just produced my own video, “Candid Conversations with a Black Business Man,” which is on YouTube, and I reference Mellody's TED Talk in that video. To me, the big takeaway is not shying away from bold conversations about race.

I've found in this moment, the post-George Floyd era, as it were, that I find black people have become more emboldened, but I have found whites have become more reserved, afraid of engaging in conversation for fear of saying the wrong thing, or being labeled a racist, or being judged, or putting their foot in their mouth. The list goes on.

I want to call out Mark and just applaud you for reaching out to us to have this conversation. I don't know whether it was a comfortable place for you to go or not, but I commend you for going there regardless, to have this dialogue.

Mark: I'm in the midst of facing those fears and trying to work through them. [laughs] I think we often want to treat people fairly, but that doesn't mean glossing over differences in culture.

In the book, you talk about, something for me to explore, the pressure to fit into a predominant culture, which is a white culture, while still staying true to your own identity.

As a white person, I think there's always that fear of like, if it's celebrating difference, runs the risk of like, “Oh, my gosh, I don't want to say something that's a stereotype or something that's offensive.” Can you talk a little bit more about that dynamic of staying true to yourself versus working to fit in or changing the culture?

Dr. Pinkett: Yeah. The book, as you know, is the work product of our lived experience, but also having interviewed dozens of other African Americans who have succeeded in their respective fields, corporate America, entrepreneurship, faith-based, nonprofit, education, and asked them,

“How did you make it to the top and not lose a sense of who you are?”

There's these 10, what we call game-changing strategies that are cumulative. Each strategy builds upon the next, meaning that strategy one is what we found to be the most foundational, the most foremost, the most fundamental strategy of all 10, and you just touched on it, Mark.

It is about establishing a strong identity and purpose, and the idea here is, when you are underrepresented and you don't see reflections of yourself and you see the predominant culture around you, the proclivity can be to adopt the culture, the norms of the majority.

You're the only African American, you act like white. You're the only woman, you act more male. You're the only immigrant, you try and adopt American mores.

Our argument is, if you want to succeed, rather than seek to assimilate, although we all have to manage our ability to get in where we fit in, but rather know that holding onto who you are, your identity, and knowing what direction you're going, your purpose, are going to give you the best shot at success because your identity is what grounds you. It's your anchor.

Your purpose is your compass.

It guides you, that when stereotypes come, or low expectations come, even racism or discrimination comes, without knowing who you are and where you're going, you're like a leaf in the wind.

They say you can't do it, you believe them. They try to deny you, you allow it to happen. You aren't grounded or guided from a sense of purposefulness and strength that can help you to overcome those challenges, and most importantly, 20, 30 years in your career, you can still look in the mirror and be proud of the person that you see.

Dr. Robinson: Here's how it intersects a lot with corporations in corporate America. The coping strategy of many people of color, black people included, is to bring a facade to work. You bring a version of yourself to work, and that's the one that is interacting with your colleagues.

That's not a very authentic approach. It doesn't bring your authentic self into the workplace, and so there's two ways to look at this. Some people will say, “OK, well, that's just how it is in a corporation. I've got to bring my mask of the corporation, and then I'm going to act a certain way and interact a certain way.”

No doubt every company has its culture, and there's some adaptation, and perhaps everybody does this to a certain extent.

I would argue that many people of color do it more than everybody else because their authentic self, their culture that they bring from their life often is either in conflict, or in some cases, just not rewarded, just not acknowledged, just not thought of as being part of the executive presence or whatever it is that people say these days.

There's a lot of thought work that goes into that, and while you're trying to figure that out, you're also supposed to do your job. What other work places have figure out is, “Can we allow our employees to bring their authentic self, or as much as they feel comfortable with?”

They find that when people are able to bring their authentic self, they can relax and perform in the higher levels because they're not doing a lot of this extra work to think and rethink how they're going to say something. That's a new way of thinking.

The corporation of the '70s and '80s was, “You suit up, you come in, and you take on the persona of whatever the company man or woman is.” What we're seeing, and hoping, in some cases, in 2020, is that companies have started to see that that forcing people to conform in those cases has detrimental effects in long term.

Mark: I admit that until recently, I had not thought much about the phrase white privilege, or the relativity of that.

I think, as you're describing it, the privilege or the luxury of not being distracted from my own work and attempts at progressing in my career by those thoughts of, “Am I being given a fair shot because of the color of my skin? Am I fitting in? Do people feel like I belong here?”

I'm just thinking back to college when I was doing an internship at one of the automakers outside of Detroit. One of the other engineering interns, who was black, he told a couple of us — the rest of us were white, so he was very much a black face in a white place — over lunch telling us a story about how he cut off his dreadlocks before he came and interviewed for the job because he feared that that wouldn't be seen as professional.

This was over 25 years ago, but I can't imagine that's gone away.

Dr. Robinson: Yeah, certainly in some places it hasn't. That's an example, the whole discussion of hair for men, but for the longest time, it was a conversation focused on women in the workplace, especially women of color, “What hairdo do I bring to work?” and then people keep focusing a lot more attention on you because of your hair or your appearance.

There are people who've written about this for sure, talking about how they have to navigate a completely different situation, from the time you leave your home to getting to work, and, “How do I look, and how does this look fit into the corporate norm?”

Back to white privilege, white privilege is, “Well, I don't even have to think about that. I just go in and be who I am,” but the fact is, who you are is reflected in everything around you inside of the company, or for that matter, society.

That means that you don't have to worry about hair, or how you look, or how people are going to perceive you if you contradict them, or other things. That's the way that things are, so it's everybody else that has to come into that.

That's why in this moment in 2020, we are all focusing more attention on, what does inclusion mean?

How do we reduce the levels of white privilege in our companies, so that we can engage everyone in their authentic place and get the highest performance in order for us to achieve our goals?

Mark: You mentioned earlier, Jeff, you talked about the dynamic of someone being the first black man to reach a certain position, or the first black woman.

I wanted to ask a question about something I see as a disturbing pattern on LinkedIn, where for one, I'll see a headline, and my reaction is, “Well, good. Great. Congratulations. It's about time.”

You see, “The first black woman hired as such and such,” and then the inevitable triggering of other white people who jump in with comments, varying degrees of rudeness, like, “Well, why does that matter? Shouldn't it just say, ‘So and so got hired'? Just use her name,” and, “Why do we have to point that out?”

Do you have thoughts on why that's necessary to call out and celebrate when somebody is the first to reach a certain position? Even seven… How many years since Jackie Robinson in baseball, there were still these firsts. Why is that worth calling out and celebrating?

Dr. Robinson: That's a great point, and certainly it goes back to that conversation about colorblindness. Some people don't want to see color, and so it offends them in some way that we're acknowledging that somebody is the first.

When Randal, and I've talked to him about this before, part of it is certainly about signaling to the public, “Hey, we are an inclusive company,” but there's a part of me that also says, “Why did it take so long? It's 2020.” [laughs] Randal, I know you like this subject. Go ahead.

Dr. Pinkett: [laughs] I hasten to echo your comments, Jeffrey. It is absolutely rooted and connected to the myth of colorblindness.

It is important, we believe, to celebrate and to highlight these accomplishments because of the exact example I gave earlier from Dr. Mae Jemison, that these are both signs of progress and signs of hope, signs that we've made progress in our society, like when we celebrated Barack Obama's election.

I was proud in that moment to see that every news outlet that I turned to, regardless of their partisanship, celebrated the moment, of what it meant for our country.

In an equal measure, because there are still hurdles we haven't overcome, there are still barriers that remain standing, and there are proverbial glass ceilings that have yet to be shattered, the struggle continues.

I want to know that University of Pennsylvania hired a black woman as their dean for their business school because now I know University of Pennsylvania has sent a message to me that in that moment, and through that measure, they are more inclusive, more diverse, more equitable, and more a sense of belonging by my estimation than they were before. It's a sign of progress and a sign of hope.

Mark: Randal, when you talk about being the first, I was going to ask this, so I'll go ahead and segue to it, you were, I think, quite famously the first and only, as it turned out, black winner on “The Apprentice,” and you were treated very differently as the winner.

I invite you to tell the story, if you don't mind, about what happened, and some of the dynamics of why you were treated differently than the other winners.

Dr. Pinkett: I should mention that this is, it's fresh on my mind because my daughter found the episodes of the show online, and we ended up watching the entire season together, which was a fascinating way of reliving the experience through the eyes of someone who wasn't even born when it happened.

[laughter]

Dr. Robinson: That's right.

Mark: Wow. You probably haven't watched it yourself in a very long time.

Dr. Pinkett: Not from end to end. I've seen snippets, but not from the beginning to the very end. I really enjoyed the journey, but to your question, there were seven seasons of The Apprentice, six where there were white winners, and then one where I was the winner. I'm the only person of any color to have won on The Apprentice.

I was season four, so I was right in the middle of the run of The Apprentice. After I was hired, and for those who are listening and watching who aren't familiar with the show, it's 18 business people who compete every week on a task.

There's a losing team, someone is fired, all the way down to the final two, live television. Jeff was in the audience, Lincoln Center, 14 million people.

I was hired in that moment, and without getting into too much detail of my performance against my adversaries, which was not equally matched, moments after being hired, I was asked,

“Randal, do you want to share the title with the white female runner-up?”

My thoughts then are quite proudly my thoughts now. It was insulting. It was a moment where people asked…

Let me cut ahead. My response was,

“If there's going to be a winner tonight, it's going to only be one, and it's going to be me.”

That was my response. I know that because I just watched the episode recently.

[laughter]

Dr. Pinkett: People kept asking, “Well, why didn't you share, Randal? Why didn't you do the magnanimous thing and share?”

My response is, “No, no, no, no, no. Not why didn't I share. Why did he ask the question in the first place? If there were three whites before me who were not asked to share, and there were three whites after me, who were not asked to share, why am I being asked to share? So the question is not on me, the question is on him.”

I would argue that in 2020, we had the benefit of hindsight being 2020, no pun intended, 2020, that it was only a harbinger, my estimation of things to come from the man who would now occupy the White House, that he didn't want to see me as the sole and single winner. My message that night is my message today, my message to my daughter.

I said this to her in that moment and she's watching and say, “Why did you do it?” I said,

“Let me tell you what. Know this. When you've earned the victory, don't be afraid to claim the victory and I claim what I rightfully earned.”

Mark: Those were the rules of the game. My wife and I watched every episode of that season. We were cheering for you. I claim MIT connections and I had only met you briefly at school, but that was a powerful connection and we're rooting for you.

Thinking back to, along the way, that moment was surprising but were there biases or mistreatment, prejudice that came out along the way during those different weeks of those competitions, or in boardroom moments?

Dr. Pinkett: It's a great question. The mechanics of the filming of The Apprentice is that we actually have very little contact with Donald during the filming because he's largely there to announce the task, go away, come back tell you who won, go away.

Only if you lose do you see him again in the boardroom. As the winner, I didn't see him much in the boardroom. I didn't have much substantive contact with Donald during the filming of the show. The answer to that questions is actually no.

Although I did hear the rumors leading up to the finale that he was considering asking me to share, or that he might consider a double hiring. Jeff knows because we prepared — he and I and our executive team at BCT — for the various scenarios, including close to the one that unfolded.

Then I worked for the Trump Organization after I won and there I began to see a different side.

To our whole conversation, I was the only person of color in any executive capacity for my entire year in the Trump Organization.

Donald at the time had some order of 30 companies under his umbrella, many which are now gone and defunct.

I met many of the executives who run those companies, mostly white men. It said something to me about does or does not Donald values diversity, as he valued equity, as he valued inclusion, as the guy who he has to share, does he value me? I can only draw the conclusion from his pattern then and now but the answer was no.

Mark: It's interesting to think about that being a prize. I'm sure it was education that…

Dr. Robinson: [laughs]

Mark: … was maybe not what you were hoping to get when you first applied to be on the show.

Dr. Robinson: The prize was education. Yeah. [laughs]

Dr. Pinkett: I have no regrets. I had a great run on the show. It opened does. People hear me talk critically about Donald as if I'm not appreciative of what The Apprentice has done for me. Quite the contrary, I am quite appreciative of what The Apprentice has done for me.

We wouldn't be having this conversation were it not for The Apprentice. I have to be true to myself and say that I can be appreciative of the door that was open, but also be critical of the person who opened the door. That's the juxtaposition that I find myself.

It was a great price, opportunity, platform, however we term it, but I'm also critical of Donald in the same vein as we all have our work to do, Lord knows, Donald has his work to do.

Mark: Jeff, what are your recollections of some of that scenario planning, or trying to anticipate what was going to happen there.

Dr. Robinson: There was a serious effort. We had to play out different scenarios, different situations that could happen, and try to anticipate the reaction. The reality is we knew that if he answered the way that he actually did, there would be some blowback.

There would be some people out there that would not like the fact that he didn't share or whatever. We said, “

OK. Randal, are you willing to take on that heat to stay on principle?”

He was and I'm glad that he was.

There was a robust group of folks out there who were very antagonistic towards Randal in that moment, and then just watching the whole thing happen live is amazing. As you already know, we start the book with the whole conversation about how, as Randal described it, how it all went down.

That became an organizing kind of story for the beginning of our book. It's been a few years since we've written it now. I'll tell you the truth, when we wrote the book I thought, “Oh, we got President Obama in here. Things are getting better.” By the time my children are old enough to read this book, it won't even be that necessary.

[laughter]

Dr. Robinson: Let's just say I was wrong on that one and now we're on to the next book.

[laughter]

Mark: The next book, Black Faces in High Places. Jeff, do you have an estimated release date on that one?

Dr. Robinson: Our estimate is Black History Month 2021, our manuscript is due in November and we're behind right now [laughs] we need to catch up. Knowing the publishing cycle, as I believe we do, we're probably looking at, at best, a late 2020, at best an early 2021 release of the book.

We're really excited about this project. The first book was very well-received and we've gotten a positive feedback. It went paperback and the like. This second book is a continuation of the conversation that we've been having about how you navigate in these environments.

I will contrast the two works to say that the first book is about how do you get to the top, and the second book is how do you stay at the top?

Mark: Thinking about the books, was your target audience, I could see benefit, I imagine the live target was providing advice to, let's say, black students and black people who are early in their career. Then as a white reader, there was perspective sharing that was certainly interesting and helpful.

I was wondering if you could touch on that. Something else I wanted to ask is turning white places into more inclusive places. What can, what should, what do white people need to do? Because that burden falls here.

Part of my discomfort I don't even like to call myself a white person. That doesn't exactly roll off the tongue. Forgive my awkwardness over stumbling through the question there. What are your thoughts there? I was asking about target audience for the book, but then I'd rather question what can we do to help create more inclusive work places?

Dr. Robinson: Which one do you want to take there, Randal? Number one or number two?

[laughter]

Dr. Pinkett: I'll follow you. You can pick and then I'll pick up what's left.

Dr. Robinson: The book certainly has an audience with black professionals from different sectors of the economy. We also know that the book has been useful for whites who read it, or for people of other ethnic backgrounds who read the book. They want to get a perspective.

We wrote a book from a distinctively black perspective from our own experience and experience of others. This certainly has application to others. The principles and thoughts, the strategies, certainly apply to anybody who've been in the situation where they're the one or the only one.

Or they get to a certain — in a new book content — getting to a certain part of the organization, the higher heights and asking themselves the question, “What are my responsibilities? How do I think about getting here and then how do I think about staying here? How do I think about the people who are coming behind me?”

Those are some of the things that I'm sure many people will resonate with. We wrote it with the black community of professionals in mind.

Dr. Pinkett: To the second question of how do we create more inclusive work places, I will distil it into three steps. I'm thinking about organizations in particular, but let me actually contextualize it two ways.

From an individual perspective, it begins with us.

We have to do the work of educating ourselves on issues of equity. Part of that is introspection, raising our awareness of our biases. We talk about cultural competence as being comprised of four components — cultural awareness, cultural knowledge, cultural skills, and cultural encounters.

Building your awareness of your biases, building your knowledge of different culture, building your skills around cross cultural communication, negotiation, conflict resolution, and then challenging yourself to move beyond your comfort zone to have encounters with difference.

You can take it along any line. Different religions, different ideologies, different ethnicities, different cultures, different languages, different political ideologies, etc. That's the individual conversation. The organizational one is about assessment, alignment, and action.

Let's assess where we are. Each organization has a different profile of where it has strengths and where it has limitations. Let's get the evidence to know what we need to measure so we can manage ourselves towards improving like we would any other initiative.

Whether it's marketing, sales, or operation, we get the data to build the case, to build the plan. The assessment to the alignment, the alignment says build a plan that aligns with our organizational identity, mission, vision, values, and our strategic direction so that we can get leadership buy-in, we can get the business case for how this can add value.

We can have alignments across all levels of the organization so that we're galvanized to facilitate transformative cultural change. Then let's take action. Like any other initiative, let's do the training, let's hold the town halls, let's expand our recruiting partnerships, let's analyze our pipeline to figure out where we have attrition, so that we can bolster our efforts.

Let's just take action to feedback to where we started, just the evidence so that we're measuring ourselves, and you can appreciate this, Mark, because I know where you come from, continuous improvement. I know you've talked about that more than once in this program — continuous improvement.

Mark: [laughs] With improvement, often comes talk of innovation and Jeff I want to ask you a little bit about your work at Rutgers Business School, and try to help the innovation economy, helping that be more inclusive. Is there also a real business case?

Dr. Robinson: Oh, yes. I'm glad you started that way. There's certainly a social justice imperative to these things.

Let's talk about the economic imperative here. You had to think about this in a micro sense and a macro sense.

In the micro sense, there is inclusive teams, diverse teams, can outperform, can be more creative than teams that just have monochromatic, that are monolithic in some ways. Not only is the group thing that goes on there to get to the more creative solutions.

Either you can make those big full pods, I see all kinds of companies make these major mistakes in terms of how they advertise and market their products, or how they are engaging the people they want to buy the products because they didn't have diverse team engaged in putting together the plan. Those are facts.

There's a lots of research studies that talk about diverse teams, and the value of diverse team in terms of a business case and getting to the best solutions, but especially in creative work, and especially in work where those different perspectives can be valued and utilized. There's a specific case there.

On the macro side of things, you can't maintain the national innovation edge that we have right now in the United States without engaging the energies, the efforts of all the people in the US. As demographics begin to change, if we're only relying upon white males as the sort of generator of innovation, that's going to leave us in really bad place.

What we need to be doing it making sure that innovation includes everybody. That it includes women. That it includes people of color.

That it includes people of different perspectives and brings them to the table, not only to create better products, or better technologies, but also to engage in the long haul in promoting and creating this innovation mentality.

That's the economic case. That's the business case. A lot of my work at Rutgers these days is around thinking about that in tech firms, in venture firms, in the STEM-type line, but certainly in how we fund and support innovation in the country.

Mark: It seems like one other way looking at it, if you're selling products to a very diverse market, having a team that's not diverse is going to create blind spots in what you think you know the market wants in different…

[crosstalk]

Dr. Robinson: That's right. That's absolutely right.

Mark: I really want to thank both of you. I do want to make a point and bring it back to The Apprentice once more for anyone who had accused Randal of not sharing, I had reached out and asked Randal to do a podcast and very immediately he said we should share that with Jeff.

[laughter]

Dr. Robinson: That's right.

Mark: Your character coming through there in terms of, my gosh, willingness to share. I really appreciate letting me ask some questions even if they come from a place of awkwardly trying to figure out, and trying to learn. Thank you for allowing that, and for being guests here today on what I know are very busy schedules.

Our guests have been Dr. Randal Pinkett, and Dr. Jeffrey Robinson. Is there anything else? I can give you the last word if there's any other final thought you want to share with the audience there?

Dr. Pinkett: I will say this, continue the thread that you laid out, and say this is how change occurs. It's through dialog. It's through moving beyond our comfort zone into our growth zone. I say all the time and I'm going to say it now, into that discomfort, Mark, because that means you're growing. That means you're a better person today than the one you were yesterday.

Don't see the discomfort as bad now that you say that you thought it's bad. I'm excited to know that you've challenged yourself to have this conversation. Even if it was at times awkward or difficult to navigate, you flexed your muscle of cultural competence which means it's now stronger.

You can test it out in one-on-ones, and then two-on-ones, and the next thing you know it's a hundred-on-ones where you're able to find your voice in greater measure. To get back to where I started with one of your early questions talking about the moment now where white people may be more iridescent, we need your voices now more than ever.

I think you not just for the invitation, but thank you for your voice and for engaging in this dialog, and moving us all from our comfort zone into our growth zone. Thank you, Mark.

Mark: Thanks. In my defense, I could be plenty awkward talking just about anything.

[laughter]

Mark: I don't worry about that reflecting badly on all MIT graduates who I know are white people.

Dr. Pinkett: Equal opportunity here.

[laughter]

Mark: Jeff, is there anything else that you would…?

Dr. Robinson: No. Randal said it well. We thank you for having us on the show.

Mark: Thank you very much. Take care.

Dr. Robinson: Thank you.

Thanks for listening! Please rate and review the podcast in your favorite podcast app.

Please scroll down (or click) to post a comment. Connect with me on LinkedIn.

Let’s build a culture of continuous improvement and psychological safety—together. If you're a leader aiming for lasting change (not just more projects), I help organizations:

- Engage people at all levels in sustainable improvement

- Shift from fear of mistakes to learning from them

- Apply Lean thinking in practical, people-centered ways

Interested in coaching or a keynote talk? Let’s talk.

Join me for a Lean Healthcare Accelerator Trip to Japan! Learn More