Scroll down for how to subscribe, transcript, and more

My guest for Episode #521 of the Lean Blog Interviews Podcast is José R. Ferro, PhD, a Senior Advisor with the Lean Enterprise Institute and the Founder and President of the Lean Institute Brasil.

By founding Lean Institute Brasil in 1999 to disseminate the principles and practices of lean thinking to Brazilian companies, Ferro helped catalyze a global movement to establish lean institutes in other countries, which ultimately grew into the Lean Global Network, chartered in 2007.

In the late eighties, he was a visiting scholar in MIT's International Motor Vehicle Research Program (IMVP), which introduced the term “lean” to describe Toyota's revolutionary management system.

Ferro received PhD and master's degrees in business administration, Getulio Vargas Foundation, and production engineering from the University of São Paulo in São Carlos.

His new book, Daily Management to Execute Strategy: Solving problems and developing people every day, is available now.

In today's episode, José will share practical insights on how to integrate daily management with strategy, the critical role of psychological safety in fostering problem-solving and improvement, and lessons learned from decades of leadership and Lean practice.

So, stay tuned for an engaging conversation about Lean, leadership, and creating cultures that thrive on continuous learning and improvement!

Questions, Notes, and Highlights:

- José's Lean Origin Story: How did you first encounter Toyota-related practices, even before the term “Lean” was coined?

- Initial Impressions: What was your perspective on Lean's balance between efficiency and a humane approach in its early days?

- Brazil's Lean Journey: How did the opening of markets in the 1990s influence Lean adoption in Brazil across industries?

- Daily Management Framework: How do you define daily management, and what are its key elements?

- Challenges of Implementation: Why is there often a gap between technical Lean tools and the social aspects like leadership and problem-solving?

- The Book's Framework: Can you explain the three foundational blocks of daily management from your book?

- Leadership's Role: What's the leader's role in connecting strategy to daily execution?

- Psychological Safety: Why is psychological safety so foundational, and how does it coexist with challenging environments?

- Problem-Solving Integration: How can organizations better connect daily huddles with deeper problem-solving efforts?

- Examples in Practice: Can you share real-world examples of organizations successfully applying your daily management framework?

- Future Vision: Where do you see opportunities for Lean to grow in Brazil or globally, especially in non-traditional sectors?

The podcast is brought to you by Stiles Associates, the premier executive search firm specializing in the placement of Lean Transformation executives. With a track record of success spanning over 30 years, it's been the trusted partner for the manufacturing, private equity, and healthcare sectors. Learn more.

This podcast is part of the #LeanCommunicators network.

Full Video of the Episode:

Thanks for listening or watching!

This podcast is part of the Lean Communicators network — check it out!

Automated Transcript (Not Guaranteed to be Defect Free)

Hi, welcome to the podcast. I'm your host, Mark Graban. Our guest today is José Ferro. He is a senior advisor with the Lean Enterprise Institute, and he's also founder and president of the Lean Institute Brazil. He founded the Lean Institute Brazil in 1999 to disseminate the principles and practices of Lean thinking to Brazilian companies. He's helped catalyze a global movement to establish Lean Institutes in other countries, which ultimately grew into the Lean Global Network, officially chartered in 2007.

In the late 1980s, José was a visiting scholar in MIT's International Motor Vehicle Research Program, the group that introduced the term “Lean” to describe Toyota's revolutionary management system. Jim Womack and Dan Jones and others who were involved in that program, of course. José received Ph.D. and master's degrees in business administration and production engineering from the University of São Paulo in São Carlos. So, José, welcome to the podcast. How are you doing?

José Ferro: Hi. I'm doing fine. Thank you for inviting me, Mark. It's a pleasure talking to you and the people that listen to your message.

Mark Graban: Yeah, I'm glad that you're here. I'm glad I was able to see you in person in September in São Paulo. I want to give thanks to the Lean Institute Brazil for inviting me to give a talk at the healthcare conference. And so it was great.

José Ferro: That was a pleasure. It was a pleasure having you, Mark, in the healthcare event. We are trying to influence healthcare in Brazil. It's a very vital sector for society.

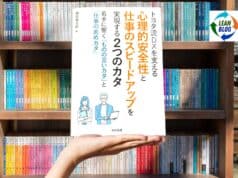

Mark Graban: Yeah, there's a lot of enthusiasm and participation with Lean in Brazil's healthcare sector. We'll come back and talk about that. We'll talk more about José's new book. I'm going to hold up here. Thank you to LEI for sending me a copy. Daily Management to Execute Strategy: Solving Problems and Developing People Every Day, co-authored by José. And we'll talk more about the book, but it's available now, translated from the original, originally published in Portuguese, right?

José Ferro: Yes, yes, that's right. And it's been translated to Spanish as well.

Mark Graban: Well, it's going to help spread through the Lean Global Network, right?

José Ferro: Yeah, yeah, that's right.

Mark Graban: We're going to talk about the book. We're going to talk about all sorts of things here today. But you know, José, I like to ask people their Lean origin story. I think maybe we heard a little bit of it in your bio, you know, with the IMVP. But I'd love to hear in your words, how did you first get introduced to things Toyota-related, even maybe before it was called Lean?

José Ferro: Yeah, yeah, it was a discovery for me and of course for a bunch of other people at that time. In the 80s, I was an academic. I was doing research in different areas. I had done a master's thesis about the automobile sector in Brazil, in particular, the auto parts industry. That thesis became a book that was available in Portuguese. Some of the MIT researchers found that out and tried to engage me in the overall global research.

At that time, I wasn't really into the auto industry. I was into other academic issues. Then there was an opportunity to go to MIT to pursue my academic interest in some areas. At that time, I was pretty much involved in organizational culture–it was a new topic in the academic environment. So, I found that very useful to everybody. And at the same time, I met Jim Womack. And Jim said, “Well, why don't you come here? Why don't you translate the materials you have and just be around these guys here?”

That was an exciting moment, Mark, because Jim was able to collect researchers from all over the globe–Japanese, Koreans, Europeans. That was an exciting moment. Bit by bit, I was able to better understand the auto industry and their perspective. Gradually, I got more involved in the work. And I really discovered Lean by accident, by going to the gemba. Of course, the numbers were showing that Toyota had discovered a new approach, a new method, with outstanding results.

But I had, from an academic perspective, different ideas. I was a bit naive about the auto industry. I was in love with some of the Swedish approaches called the sociotechnical approach. They were trying to make work more humane. There was a lot of discussion about the Japanese model. Gradually, I got involved in the research, collecting data about Toyota and others.

My “aha” moment came when I visited a Honda plant, a motorcycle plant, in the middle of the Amazon jungle. Because of government policies, they were trying to industrialize the Amazon region. Honda had a huge motorcycle plant there. When I visited, I saw some of the elements Toyota had developed, and it really struck my attention. I thought, how can you do that in the middle of the jungle with that kind of labor? That was my discovery moment. I joined the team when I saw something absolutely unique, different, and remarkable.

Mark Graban: And I think in that search for a more humane approach to manufacturing, leadership, and workplaces, I think that ideal is found, at least in the Toyota Production System and Lean–not just having a customer focus, but an employee focus hand-in-hand.

José Ferro: Yeah, Mark, I discovered that much later. At that time, I thought Lean was only an efficiency approach–just becoming more efficient. The humanistic approach in Toyota's system, to me at that time, was about quality circles, involving people doing kaizen. It was a very superficial understanding of what the Lean system is, especially the leadership and human approaches.

Understanding how central knowledge creation and engaging all people were took me time–decades, actually–to move from tools and efficiency techniques to a complete management system where knowledge, capability development, and leadership are fundamental. That's why one chapter in my book focuses on execution–how to engage people and lead the daily management process effectively. You can design beautiful boards with the right KPIs, but if you don't engage people or lead properly, you won't succeed.

Mark Graban: Yeah. So I want to dig into the book. I'm curious, José, after your time working with Jim and the IMVP, did you come back to Brazil? Were you in academia during that time before starting the Lean Institute in Brazil?

José Ferro: Yes, I was involved in academia. But because of the research I had written, Mark, some papers became very influential in Brazil. In 1990, exactly when I was coming back to São Paulo–remember, this was before the Internet, before cell phones–communication was much harder. I had written a paper that used a metric called “design age,” one of the metrics from the MIT program, to evaluate how modern an industry was.

At the time, the design age of the Brazilian auto industry was very high, meaning it was producing very old vehicle designs. The Brazilian market was protected, with no imports and only a few multinational companies–Volkswagen, GM, and Fiat–operating here. Japanese, Korean, and other foreign automakers weren't present yet. The cars were expensive, of low quality, and heavily taxed.

In 1990, we had a new president, our first democratically elected president after a long dictatorship. He decided to open the market, and one of the arguments he used was that Brazil was producing outdated cars. My paper provided data that supported this argument. That led to policy changes to open the market and help the auto industry transition to become more competitive.

I helped the government design those policies and worked with companies to adjust strategies. For several years, my work was focused on modernizing the auto industry. It was important work, given the industry's economic impact and its role in employment. But I never felt that was my ultimate mission. The inefficiencies and lack of competitiveness I saw in the auto industry were present across all sectors of Brazilian society, including healthcare. I realized that the transition we were helping the auto industry make was needed in nearly every other sector in Brazil.

Mark Graban: And that realization led you to broader Lean work?

José Ferro: Yes, in the late 90s, when Jim Womack wrote Lean Thinking, I invited him to Brazil. We had a Portuguese translation and even added a local chapter. Jim told me about his vision for the Lean Enterprise Institute–a nonprofit in Cambridge to disseminate Lean knowledge. He had initially believed that The Machine That Changed the World would lead people to adopt Toyota's approach naturally, but he found it wasn't that easy. The knowledge wasn't obvious or intuitive.

I connected with Jim's vision. I had been in academia, but the environment wasn't conducive to the type of practical work I wanted to do. Consulting also wasn't my thing. I wanted to translate Lean ideas into education and knowledge-sharing. That's how the Lean Institute Brazil was born–to spread Lean principles to all industries in Brazil.

Mark Graban: That's incredible. So now, let's dive into your book. How do you define daily management, and what are its key elements?

José Ferro: Most companies have some form of daily management, even if they don't call it that. For example, hospitals in Brazil often hold daily huddles–brief meetings near the gemba to review operations and discuss issues. In software development, you might hear about stand-up meetings. These are helpful for communication but often lack structure.

In our book, we propose a more integrated daily management framework with three blocks: commitment, control, and problem-solving.

The first block, “commitment,” is about linking the organization's strategy to the specific purpose and goals of an area. It's about defining what that team or process needs to deliver and why it exists. Each area in a hospital, for instance, has a unique purpose. The pharmacy's purpose is not the same as radiology or the surgical center. The second block, “control,” focuses on what you're managing and measuring daily–how well you're meeting your targets. The third block is “problem-solving.” Whenever there's a gap or a “red” metric, there needs to be a structured approach to identifying and addressing the root causes.

Mark Graban: That's really insightful. One thing that stood out to me in the book was the emphasis on psychological safety. Why is it such a cornerstone for daily management?

José Ferro: Psychological safety is essential because daily management is, at its core, an educational process. It's about engaging people in understanding their work, identifying problems, and proposing solutions. For that to happen, people need to feel safe to speak up without fear of blame or punishment. This idea goes back to Dr. Deming's principle of eliminating fear.

Psychological safety doesn't mean avoiding challenges or discomfort. On the contrary, it's about creating an environment where people feel safe to take risks, suggest ideas, and address problems openly. Leaders must challenge teams to improve while fostering an atmosphere where learning and experimentation are encouraged.

Mark Graban: I completely agree. I often see organizations where they hold daily huddles but struggle to provide time or resources for deeper problem-solving. They end up discussing the same issues over and over. How does your framework address that?

José Ferro: That's a common issue. Daily huddles are great for quick communication and alignment, but they're not enough for problem-solving. In our framework, problem-solving is its own dedicated block. When a problem arises, the immediate focus is on containment or mitigation, but it must also trigger a deeper root-cause analysis.

We emphasize making the problem-solving process visible and connected to the gemba. Problems shouldn't be outsourced to a separate department or left unresolved indefinitely. The team closest to the issue should take ownership, with support from leaders and resources as needed.

Mark Graban: That makes a lot of sense. José, thank you so much for sharing your insights. There's so much more we could discuss–real-world examples, deeper applications of the framework. I'd love to have you back on the podcast to continue the conversation.

José Ferro: Thank you, Mark. I'd be delighted to return. Next time, we can dive into specific examples of organizations applying these ideas and the results they've achieved.

Mark Graban: That sounds fantastic. Thank you again, José, and congratulations on the book!

Episode Summary

What do you think? Please scroll down (or click) to post a comment. Or please share the post with your thoughts on LinkedIn – and follow me or connect with me there.

Did you like this post? Make sure you don't miss a post or podcast — Subscribe to get notified about posts via email daily or weekly.

Check out my latest book, The Mistakes That Make Us: Cultivating a Culture of Learning and Innovation: