Professors Robert H. Hayes and William J. Abernathy have harsh words about a common, if not typical style of American management:

“…an overdependence on analytical detachment – what they call ”managerial remote control.”

They say it is an approach that exalts financial analysis, not line operations. It rewards executives who see their company primarily as a competing set of rates of return, who manage by numbers and computer printouts.

Further, they say, it is a seductive doctrine that promises the bright student a quick path to the top and that piles its rewards on executives who force through impressive short-term performance, at indeterminate cost to long-term health.

Fearing any dip in today's profits, American companies keep research and technology on short rations, skimping the investment critically needed to insure competitiveness tomorrow.”

These are warnings about:

- Prioritizing financial analysis over an operations focus

- Emphasized and rewarding short-term performance over long-term perspectives

Is that from a recent article that I've read? Yet another article about Boeing's troubles?

No. It's a 1982 article in the New York Times. Hat tip to Tom Ehrenfeld for sharing it with me.

The link below should be a free-to-read link even for non-subscribers:

MANAGEMENT GOSPEL GONE WRONG

They were challenging the “management gospel” that was being taught in “top MBA programs.” Such as?

“They teach that American management doctrine has drifted away from basics and neglected the factory floor and the assembly line – the front lines. That neglect and an excessive concern for short-run profits explain much about the failings of American industry, they say.”

American companies made all sorts of excuses at the time for their performance problems, including, per the article:

- “heavy-handed regulation,

- the avarice of labor unions,

- the decline of the work ethic,

- the oil crisis or

- the Japanese.”

When teaching in Switzerland, Hayes laid out some of these reasons (and others) and was stunned to hear that their response was that they had all of those same factors in Europe… but “their productivity was increasing.”

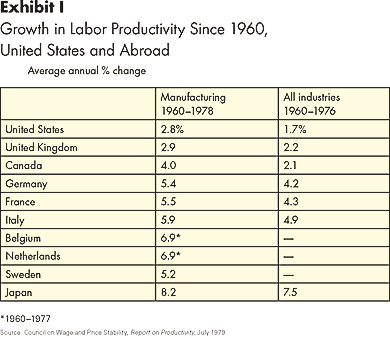

The U.S. wasn't just lagging Japan. They were lagging other countries, as this table from a Hayes and Abernathy article shows:

Hmm… so it was something else. What excuses does Boeing make today?

I'm old enough that Japan was still seen as the primary competitive threat to the U.S. industrial base when I went to MIT in 1997, to study at the “Leaders for Manufacturing” program (now called “Leaders for Global Operations“).

That program, as a dual engineering and MBA program, bucked the MBA trends by being a proudly operations-focused education for people who wanted “Big M” career paths in manufacturing companies. Big M meant all of the functions of a manufacturing company, including product development, not just the factory floor.

I remember reading some of Bob Hayes' work in our studies, primarily the Hayes and Wheelwright model.

Learning from Japan

Even in 1982, companies were visiting Japan, but there were already misperceptions about what could be learned.

“Where American business executives argue that the Japanese advantage is largely rooted in factors unique to Japan – lower labor costs, more automated and newer factories, strong government support and a homogeneous culture – Mr. Hayes and Mr. Abernathy say nonsense. They assert that the key difference lies in other factors, which American business could readily match.”

The Japanese factories weren't these mystical “factories of the future,” but more like a “present-day factory doing simple things well.”

What are the factors that companies around the world (or hospitals, even) could match? Per the article:

- “clean workplace,

- preventive maintenance for machinery,

- a desire to make their production process error-free and

- an attitude that ”thinks quality” at every stage in the production process.”

They were generalizing, of course, but the American factories were seen as having:

- “machines are overworked and abused…

- quality is viewed as a barrier to lowered production costs…

- defects are ignored and…

- management and workers are adversaries.”

I lived through all of that at a General Motors plant circa 1995. There are allegations that some of those problems exist at Boeing today.

How many of those four points are still a problem at factories (or hospitals) today??

Hayes describes what could be called “kaizen”-style continuous improvement that respects and engages people:

”We must compete with the Japanese as they do with us: by always putting our best resources and talent to work doing the basic things a little better, every day, over a long period of time. It is that simple – and that difficult,” writes Mr. Hayes.

Here we are, 42 years later… and the challenge remains! The answers are indeed simple, yet difficult!

Here is the Harvard Business Review article that's mentioned in the NYT piece:

Managing Our Way to Economic Decline

In the article, Hayes and Abernathy blame U.S. productivity problems on the “failure of American managers to keep their companies technologically competitive over the long run” and they called for “fundamental shifts in management attitudes and practices.”

I guess management attitudes and practices are a form of technology. Lean and the Toyota Production System are “technology.”

It's something that anybody can do… or hardly anybody?

Hayes and Abernathy are harsh, and they expected this article to be controversial:

“The conclusion is painful but must be faced. Responsibility for this competitive listlessness belongs not just to a set of external conditions but also to the attitudes, preoccupations, and practices of American managers.

By their preference for servicing existing markets rather than creating new ones and by their devotion to short-term returns and “management by the numbers,” many of them have effectively forsworn long-term technological superiority as a competitive weapon.

In consequence, they have abdicated their strategic responsibilities.”

Ouch.

How much of that is still true today?

Please scroll down (or click) to post a comment. Connect with me on LinkedIn.

Let’s work together to build a culture of continuous improvement and psychological safety. If you're a leader looking to create lasting change—not just projects—I help organizations:

- Engage people at all levels in sustainable improvement

- Shift from fear of mistakes to learning from them

- Apply Lean thinking in practical, people-centered ways

Interested in coaching or a keynote talk? Let’s start a conversation.