Ah, it's another year of the Academy Awards. And that means, not surprisingly, another year with news articles that don't show much understanding of performance measures over time.

You might have read a very similar post in the past… because I've written very similar posts (like this one updated in 2021), and I wrote about this in my book, Measures of Success.

I'm going to pick on the New York Times (with a free article link):

‘Barbenheimer,' and an Early Start, Boost Oscar Ratings to 4-Year High

It's a true statement. It's factually correct to say TV ratings in the U.S. were a “4-year high.” Is that worth celebrating? The context around the data… and what we learn from having more than four data points matters greatly. That's a lesson for the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, ABC television, or any business.

“ABC's telecast of the 96th Academy Awards on Sunday drew 19.5 million viewers, hitting a four-year viewership high, according to Nielsen. The live TV audience was up from last year's 18.8 million, the third consecutive year that Oscar viewership has grown.”

It's true that the number of viewers was higher than last year. One could do the math, as these articles do — it's a 3.7% increase from 2023.

That's true, but is it statistically meaningful. What conclusions should you draw, if any?

It's true that ratings have increased for a third consecutive year. That makes this year, yes, a four-year high.

True, but meaningful?

Here's a chart that I drew showing these last four years:

The chart reminds me of this scene from the Simpsons where Disco Stu looks at projections for disco record sales:

“If these trends continue…”

Oscars viewership isn't showing an exponential increase like Disco Stu's cherry-picked numbers. It seems to be approaching an asymptotic limit of about 20 million viewers. Should the Academy and ABC be happy about that?

As usual, the Times' article tries to explore reasons why ratings might be higher, including:

- Starting the broadcast an hour earlier

- Popular movies being nominated (and history shows ratings are higher in these years)

- People being happy with Jimmy Kimmel hosting for a fourth time (see this blog post about hosts and ratings)

The Times also shares data that it factually correct… but possibly not meaningful:

- The 2024 Oscars was the most-watched major awards show since February 2020

- The Grammys' viewership was up 34% compared to last year (so the Academy and ABC should be upset at their comparative performance?)

- The Golden Globes' ratings were up 50% year on year

- The Tonys' ratings were up about 10%

- The Super Bowl “beat ratings records”

So are the Oscars part of a positive trend about live event viewing? Or are the Oscars underperforming against other live event viewing growth?

Context matters.

The Oscars are not at an all-time ratings record. Far from it!

The Times explores the history and context a bit. But not as much as I would.

“In 2021, for a stripped-down pandemic Oscars held in a Los Angeles train station, only 10.4 million people tuned in. Viewership rose in 2022 to 16.6 million people, in part because of the bizarre spectacle of Will Smith slapping Chris Rock.”

Why would viewership rise BECAUSE of the Will Smith slap? Did people tune in after hearing about that on social media or something? It's not like the slap was advertised in advance… that's a strange attempt at cause-and-effect analysis.

“Still, there is no question that TV viewing habits have changed. Before 2018, the Oscars telecast had never dropped below 32 million viewers.”

Ooh, that's good context. To recap, the 2024 numbers were 19.5 million. That's huge DECREASE from 2018. Doing the math, it's a 41% decrease since 2017 (32.9 million viewers).

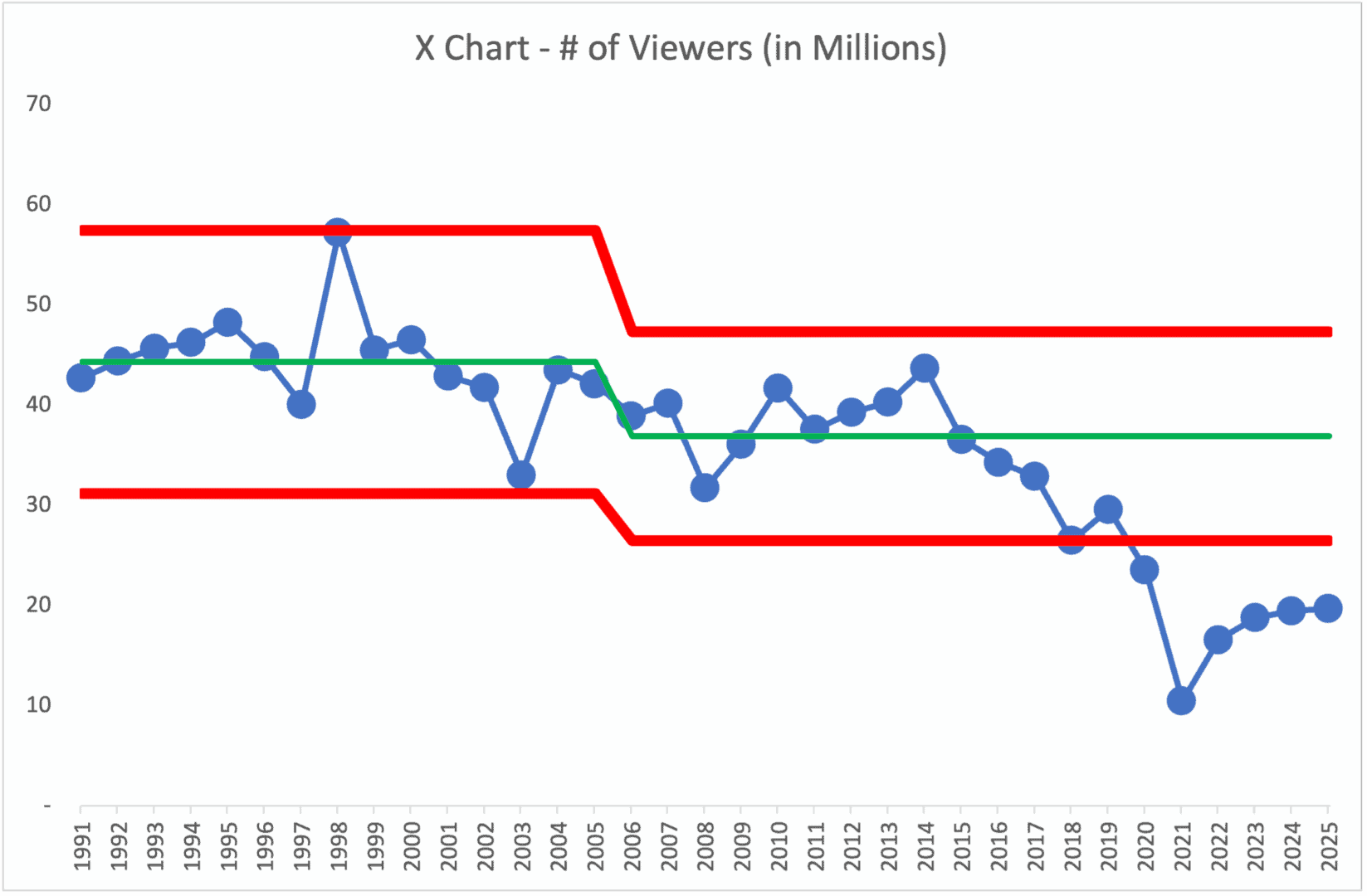

As I like to do, I've updated the Process Behavior Chart that shows the number of viewers since 1991… also updated for 2025 numbers (19.7 million viewers):

Let's ignore, for now, the Process Behavior Chart (PBC) methodology. We almost don't need that complexity to analyze the Oscars' ratings. Just look at the blue dots and lines — the actual viewership numbers.

Oh my goodness, that's a horrible downward trend over time. I mean, at least it stopped falling… but the long-term trend is bad and the long-term causes are probably easier to explain.

From Measures of Success, starting with this annotated PBC that goes up to 2018:

“[The chart] tells us the number of viewers is not a predictable system over this entire time frame, including 2018. We would not be able to predict future viewership numbers since this chart doesn't reflect a single system over time. The system has changed.

We see multiple signals in the X Chart. There is also one Rule 1 signal in the MR chart, not shown, that corresponds with the first X Chart signal.

The year 1998 is above the Upper Limit (Rule 1). This suggests there is a “special cause” that caused the system to be different that year, even though the results were not sustained. The special cause for the unusually high viewership is commonly thought to be the popularity of the movie Titanic, which had 14 nominations that year. The MR Chart has a similar signal at the same time.

There are also eight consecutive data points below the baseline average, a Rule 2 signal. We also see a cluster of three consecutive points that are closer to the Lower Limit than they are to the average (Rule 3).

The year 2018 again falls below the calculated lower limit (Rule 1). The Academy would be correct to look for an explanation or a “special cause.” Asking about any other single below-average year would likely be a waste of time.

But, the Academy missed an opportunity to start asking “What has changed?” in 2013, when the eighth consecutive below-average data point was found. What led to a downward shift in viewer numbers?

If the number of viewers was fluctuating around an average, then it's unlikely to randomly have eight consecutive points above or below the average. The eighth data point (not the sixth or the seventh) is a signal that something has changed, although it's possible the system changed at the time of the first below-average data point (in 2006).

What is the cause of such a shift? A 2012 Hollywood Reporter article points to the now-disgraced Harvey Weinstein pushing smaller-budget “indie” films for awards when those films were far less popular (think the opposite effect of the movie Titanic). It seems to suggest that one possible countermeasure for the Academy would be to just nominate the most popular films of the year, but artistic integrity would, hopefully, prevent them from doing that.

The article blamed “the exploding cable TV universe” for the decline in ratings. A systemic change like that could explain the signal of eight consecutive points below the average — and the longer-term trend. The number of TV channels seems to only be increasing. That trend isn't going away.

Other supposed explanations for ups and downs in the chart include:

- Moving the telecast from Monday to Sunday

- Viewers getting used to it being on Sunday

- The hit show Survivor was on at the same time

- 9/11

- Other world events

- New producers

- Different hosts

As a reader of this book, you realize that every metric is going to have variation. You'd know not to try to explain every up and down. With viewership numbers fluctuating around an average, the Academy could end up in a cycle where they name a new celebrity host and see ratings go up. So, they'd bring the host back again and see ratings decline. The Academy might conclude that the public has tired of the host, leading them to hire somebody else.

Dr. Deming might have used the term “tampering” to describe that scramble for possible solutions. He'd say that tampering with a predictable system would generally increase variation in the system and the metric. Instead of making thoughtful changes based on knowledge of the system, the Academy might be trying random changes that just lead to more random fluctuation, which then causes them to draw the wrong conclusions about what works and what doesn't.

Getting back to the PBC, I redrew the Process Behavior Chart to show where a shift seemed to occur in 2006, shown below. If we are discovering an emergent shift in the process, we might essentially be guessing when the new process began. An educated guess for when a shift below the old system's average began is the first data point below the old average.

The new average for the new system, with a baseline of 2006 to 2018, is 36.9 million viewers, with Lower and Upper Limits of 26.5 and 47.3, as shown below:

The number of viewers used to fluctuate around an average of 42.27 million viewers. The old system was predictable in that the number of viewers would have been expected to fall between the limits of 30.5 and 54.07 million viewers. We would have expected that system to remain predictable until something changed in the system — whether that's a one-time event (Titanic) or a technology shift (hundreds of TV channels).

The year 2018 appears to be right on the cusp of being a special cause (Rule 1). It's right on the Lower Limit line. The calculated Lower Limit is 26.50 and, with rounding, the number of viewers was reported as 26.5. Instead of worrying about whether it's precisely above or below the limit, we can treat it as a special cause, accepting the small risk that the data point is noise instead of a signal. It would most likely be appropriate for the Academy to ask “Why were ratings low in 2018?”

Again, the Academy missed a chance to ask something like “What changed in 2006 or so that caused the average viewership to drop to an average of 36.9 million viewers?” They could have detected this shift in 2013, when they would have seen the eighth consecutive point below the old average.

What is the special cause of that sustained shift downward? If the Academy could have identified what changed, it's possible they could have taken countermeasures to address it. On the other hand, if the special cause was a broader societal or technological trend, they probably couldn't take action. We'll never go back to a day of having just seven or eight channels available.

Since 2018 was the fourth consecutive year below the newest average, it's possible this is the beginning of another shift (some say it's due to the rise of Netflix this time). But, the four data points alone are not a signal.

If we have four more years below 37.4 million viewers, or if the number falls below 26.5 in 2019 (or any other future year), we'd see a signal worth investigating.

And that signal did appear in 2020… I can't imagine a future where ratings for The Oscars increase in a statistically meaningful way.

2025 Numbers

As the updated chart shows earlier in this post, viewership was up slightly from 19.5 million to 19.7 million viewers.

5 Reasons the 2025 Oscars Saw a Slight Ratings Increase Over 2024 ‘Barbenheimer' Showdown

It seems silly to come up with “5 reasons” why there was such a small change in the metric. They're making the mistake of explaining noise. They could have cited the weather or some other random factor.

Conclusion: Context, Caution, and Clarity

The Academy Awards might be up year-over-year in viewership, but headlines celebrating a “four-year high” miss the bigger picture–especially when the broader trend tells a different story.

We can't make good decisions from noise. And we certainly shouldn't celebrate random fluctuations as if they're meaningful improvements. As viewers, executives, or data-minded professionals, we should be wary of drawing conclusions from small sample sizes or cherry-picked comparisons.

What's far more useful than spinning narratives around this year's tiny bump is recognizing when a system has fundamentally changed–and asking the right questions early enough to respond.

The lesson here extends far beyond Hollywood.

Whether you're running a factory, a hospital, or a global awards show, the real work is in understanding the system behind the numbers–not reacting emotionally to every uptick or downturn.

If you want to better understand how to separate signal from noise in your own organization, check out my book Measures of Success–and explore how you can apply Process Behavior Charts in your daily management systems.

And if you're interested in learning these lessons in a hands-on, practical way, join me at an upcoming workshop or learning experience. We'll do more than just admire charts–we'll learn how to run our systems better.

Explore upcoming workshops and learning experiences

Please scroll down (or click) to post a comment. Connect with me on LinkedIn.

Let’s work together to build a culture of continuous improvement and psychological safety. If you're a leader looking to create lasting change—not just projects—I help organizations:

- Engage people at all levels in sustainable improvement

- Shift from fear of mistakes to learning from them

- Apply Lean thinking in practical, people-centered ways

Interested in coaching or a keynote talk? Let’s start a conversation.

[…] based on the large point-to-point variation in the data over time. Unlike other TV ratings (like The Oscars), there doesn’t appear to be a definitive downward trend over […]

I cant believe one of your main reasons was not the large left swing of actors and Hollywood overall over the last 15 years or so. If you swing so far one way or the other (left or right) you will lose views from about 1/2 of the population. We want to see actors act and musicians play music, not hear a 10 minute speech about why their world view is right.

Hollywood has been considered “liberal” for many decades or as long as I can remember. That was a frequent topic of Rush Limbaugh’s in the 1990s.

This article says Hollywood became “liberal” in the 1970s.

2025 ratings were, at first, said to be down a bit… but now that streaming stats are involved, ratings are up about 1% over 2024. So, it’s meaningless to even discuss “why?”

LINK