This is a repost from my blog post about a talk I gave in 2018…

I always enjoy the KaiNexus User Conference (now called KaiNexicon starting this year) and they ask me to give a talk each year.

Last year, I gave a talk called “When Being Right is the Wrong Strategy for Change” and KaiNexus recently shared a nicely-shot video of that talk on YouTube. So. I'm sharing along with a transcript I had done, annotated with some slides and links. You can also read a shorter summary via the KaiNexus blog.

tl;dl summary: Mark Graban's blog post and video, “When Being Right is the Wrong Strategy for Change,” discusses the ineffectiveness of insisting on being right as a strategy for driving change. He emphasizes shifting from a directive approach to a more collaborative one, using “Motivational Interviewing” techniques. Graban argues that understanding individual motivations and engaging in empathetic dialogue is more effective than merely directing actions. This approach aligns with Lean thinking, focusing on respect and understanding the perspectives of those involved in the change process.

Here is the video:

Podcast

This is also episode #275 of the Lean Blog Audio podcast.

Transcript

[music]

Mark Graban: My theme here may be a bit provocative is the idea when being right is the wrong strategy for change. Now, I feel compelled to say, when being KaiRight is KaiWrong, no, we're going to do that for two things.

[laughter]

Mark: I have to be careful. I'm standing up here on this platform. When I talk about change management, I don't want to be the guy who's standing here saying, “I'm right,” because that might be the wrong strategy for getting you to think about change management and engaging others in a little bit different way.

I want to stand up here from the spirit of sharing some things that I feel like I've been fortunate to learn. There's some things I've been exposed to outside of the typical realm of lean, engineering, and business school.

I also want to share some lessons I've learned the hard way. I'm not standing up here and saying I'm the world's best change agent. I want to try to share some ideas that maybe give us all thinking about what we can do to be better change agents.

We can continuously improve the way we help people continuously improve.

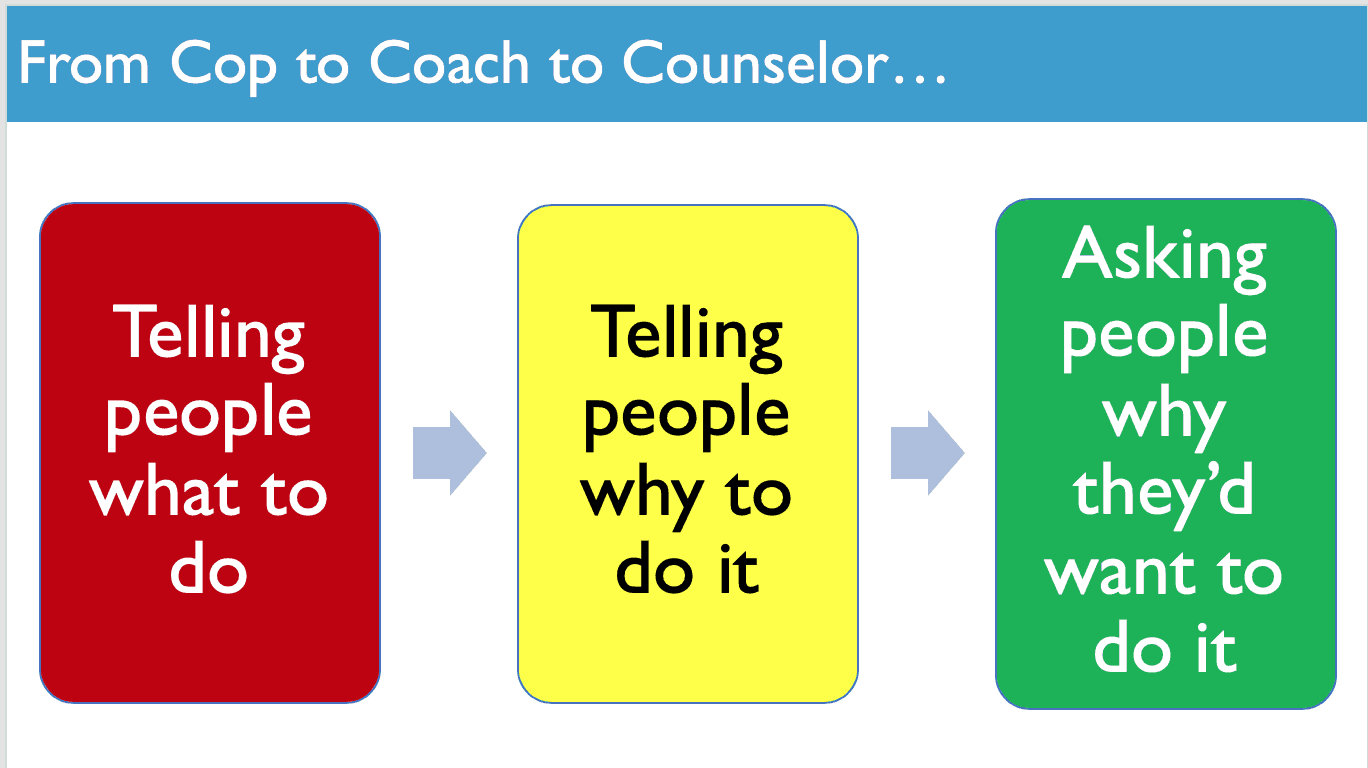

When you think about helping others, when you think of the visual here, the idea of shifting from being a leader who's a cop, who's catching people doing the wrong thing, correcting people, writing people up to being more of a coach. It doesn't mean being so obnoxiously huggy.

In healthcare, people hug. When I got into healthcare, that freaked me out. You don't hug at work. You get sent to HR. You get sent to the HR cop, I guess. [laughs] No offense to HR people who are here.

Shifting that mindset of saying, “Well, I'm going to be supportive and help coach others up instead of knocking them down when they're doing the wrong thing.” I think that's an important progression.

A lot of us would say, “We're coaches.” It sounds nicer than saying consultant. There's maybe another step we can take and this is something I've challenged myself over the last couple of years. How can I go from being a cop to a coach to maybe being more of a counselor?

I'm not a licensed therapist. I don't pretend to be one. There are some lessons we can learn from this profession. To maybe shift from the old command and control environment mindset of “Well, I'm going to tell people what to do,” or the irony of “I'm going to tell you to submit ideas.”

Wait a minute, are we engaging people in continuous improvement in a very command and control way? That might be something to pause and think about.

Telling people what to do may just result in compliance. “I did it because you told me to.” I'm preaching to the choir in this room that we aim higher than that. We want people to be intrinsically involved, motivated and excited to choose to participate in continuous improvement.

We're looking for compliance or are we looking for real change that's a choice?

In the Lean realm, we love asking “why?”. This is part of the progression of shifting from telling people what to do to focusing on the why. Starting from why focusing on motivations, goals and reasons.

I think sometimes we fall into a trap of telling people why. We don't just say, “You need to put 10 ideas into KaiNexus.” We might say, “You need to put 10 ideas in KaiNexus because it will make your job easier,” or something like that.

There are lessons from the realm of psychology and counseling that make it fairly well proven that a more effective strategy is asking people why they would want to do something. Because one of your employees might not care about making their job easier. You telling them, “You should participate in KaiNexus,” and because it makes your job easier, may have zero connection to them as individual.

Another employee might really resonate with that but different people are going to have their different motivations for participating. Engage people into a discussion of saying, “Hey, Clint, why do you think it's important to participate in continuous improvement?” It's a more effective strategy for engaging people and leading to action which is I think what we want as leaders and change agents.

We can ask why. I hear a lot of questions that start with why. Why aren't more leaders embracing Lean management? Sometimes the fingers are being pointed in a different direction. Why aren't employees speaking up with ideas? Ethan Burris who's joining us tomorrow. He's done a lot of great research at UT about why employees choose to not use their employee voice.

I'm sure he's going to share a lot of great things with us. Why are some employees not using KaiNexus? That's something some of you might be struggling with or wondering about.

Related to my new book, you might ask, “Why aren't some people using control charts? Why aren't people using statistical methods to analyze their metrics?” We do this. Within KaiNexus we use the…Has anyone else used the KaiNexus control chart functionality? I hope, please, some of you. All right, some of you do.

I might say this is the right way to do metrics. That runs the risk of creating pushback. If I'm so convinced in my rightness, it's a natural reaction for someone to say, “Well, no. I'm not going to do that because you told me to. I'm not necessarily going to do that because you're standing on a platform.”

We're to help people internalize decisions so they make choices about change. When answering any of these questions — Why aren't people doing these things? Why aren't people doing what I would like them to do? Is it because they're dumb? No. Is it because they don't care? Probably not.

It's this trap where we talk about the idea of your greatest strength can also be your greatest weakness. Learning new things, being excited about those new things, and then not just being convinced about your rightness, maybe actually being right, can be the biggest impediment to getting others to go along.

Being right doesn't mean that others will automatically follow.

As an engineer, I say — other people say this too — I hear people describe themselves as recovering engineers. What do you mean? Engineering schools really focused on calculating the right answer.

You emphasize teamwork, projects, and things, but there's this level of certainty that doesn't necessarily apply in the workplace. We focus not so much on coming up with the right thing to do, but also think about how we engage others.

I love this quote, and I use it a lot. The late Peter Scholtes:

“People don't resist change. They resist being changed.”

There is a lot of really solid psychology behind this. When people are being resistant, we shouldn't blame them. We might, maybe, step back or look in the mirror and ask, “Does that mean people are being resistant to my idea?”

Again, instead of judging them for not going along, we can, maybe, turn that around and ask for what can we do to better engage them. There's a provocative question that comes from the field of counseling. Do we as leaders or change agents…do we want to be right or do we want to help others change?

I've struggled with this. I've reflected on this. I can sit down behind the keyboard, Mr. Blogger, internationally recognized. Somebody in Toronto once said, “Hey, are you Mark Graban?”

[laughter]

Mark: I'm like, “Internationally recognized!” Do we want to be right? I've written blog posts where I look back and say, “Boy, I was writing that. I was on fire. I was on a rant. I was right.”

Did that article really do anything to create positive change in the world? It feels good to write something or say something that says, “Boy, I'm right.” [laughs] I'd like to see more change in the world than just sitting back and feeling satisfied about I was right.

I was real fortunate at a conference a few years ago. I met a licensed social worker. I was at the Lean Startup Conference. There was a social worker who was starting a non-profit startup. It was a speed networking chance encounter.

We started talking, “What do you do?” “What do you do?” We talked about Lean and trying to help people change. She said, “I think you'd be interested in this book about counseling.” I've never read a book about counseling. I've never read a psychology textbook.

There's a comparison that teed up, traditional counseling. Addiction therapy is often built around the idea of telling the patient or the client that they're wrong, “You need to stop doing such and such. You need to start doing this.” That creates an equal and opposite reaction of pushback.

Counselors have learned they can't fall back on being correct. Telling somebody they should stop doing something doesn't really impart new information to the person that that counselor's trying to help.

This is the challenge of an addiction. Think of something maybe a little bit more benign. My dentist or the dental hygienist will tell me, “You need to floss more.” I've heard that three times a year for as long as I can remember. They are right that I should floss more, but that doesn't necessarily help me change.

There are lessons around the idea we can't make others change. We can create conditions and have conversations that allow others to choose to change. That's where this more modern approach to addiction counseling, called motivational interviewing, actually has a lot of great applications in a workplace if we're trying to help others change.

We recognize that change is a process. It's not like flipping a light switch. It's a process we can help people work through. One of the key methods in motivational interviewing would be for a dentist or a hygienist to ask a question like, “Hi Mark. What are some reasons for flossing every day?” I would say, “Well, my gums will be healthier. I'll have less plaque buildup.”

These are things I know, but it didn't mean I was flossing every day. This process of asking questions and drawing out from the person you're trying to help is proven as I articulate these reasons for change, that activates the part of your brain that makes action more likely.

There is this interesting difference between being the expert who's right and telling someone what to do, versus asking them about their motivations. Hence the name, motivational interviewing. The core book that that social worker recommended to me is quite readable as far as psychology goes.

It was more readable than I thought it would be. Motivational interviewing is a collaborative — that's a key word — goal-oriented style of communication, with particular attention to the language of change. Why do people choose not to change? It's important to frame it that way.

It's not that they're not choosing to go along with you, they're choosing to keep doing things the way they're doing it.

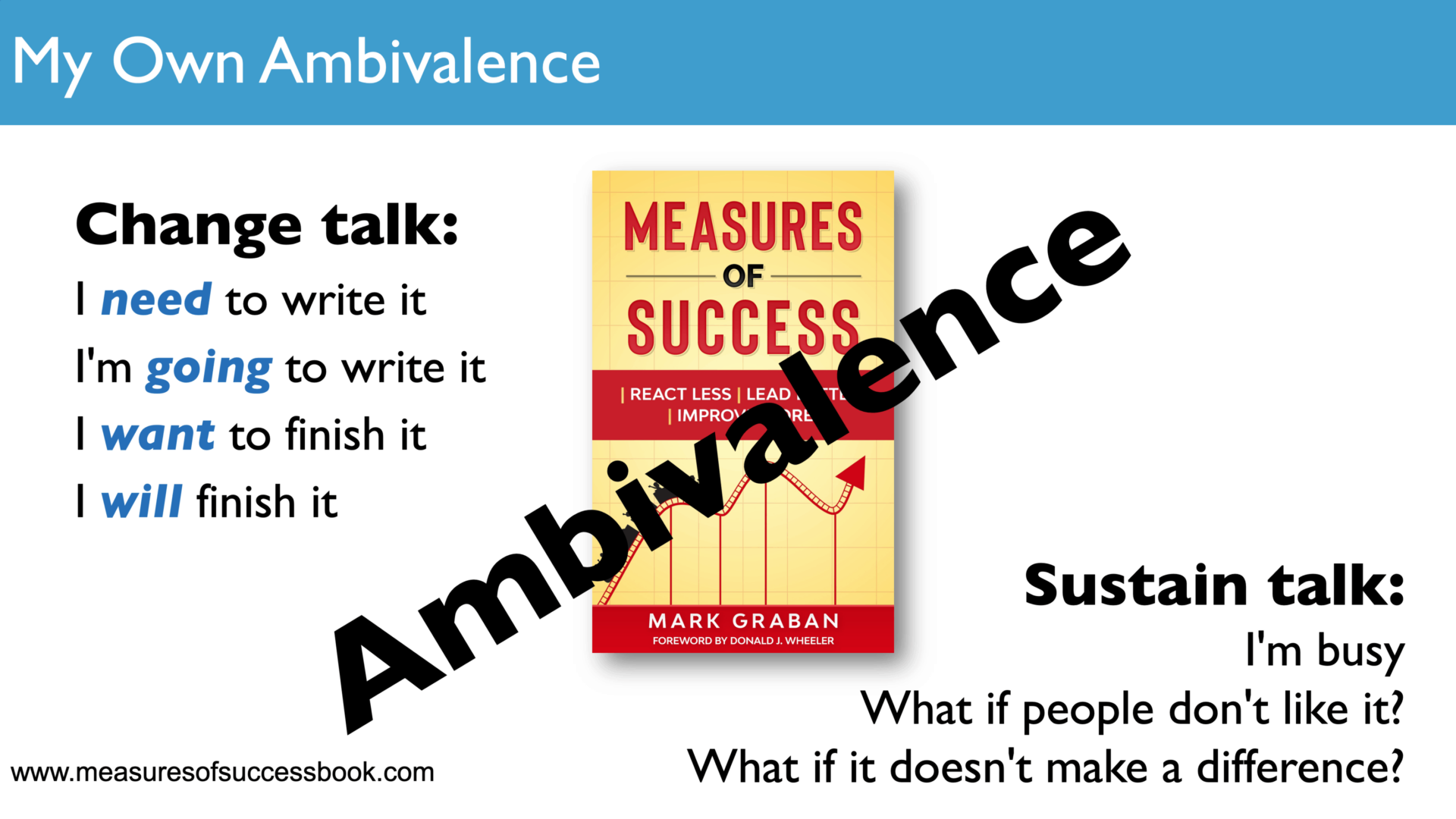

In motivational interviewing, we talk about change talk. Talk that is indicative of change and progress, versus sustain talk.

I'll share some examples here. When the sustain talk outweighs the change talk, people tend to stay where they are.

Motivational interviewing is designed to strengthen someone's personal motivation for and commitment to a goal. Within this, it's not just a matter of tools and tactics. There is a spirit which reminds me of Lean, you can say there is a spirit of Lean. This idea that you are collaborating between the practitioner and the client, which is different than putting yourself up on a pedestal as the expert.

I realize I'm saying that up on a pedestal. Evoking the client's ideas about change, emphasizing the autonomy of the client, that I respect your right to not make that change. I can sit behind a keyboard as a blogger and complain about executives who aren't embracing Lean in healthcare. Does that really help?

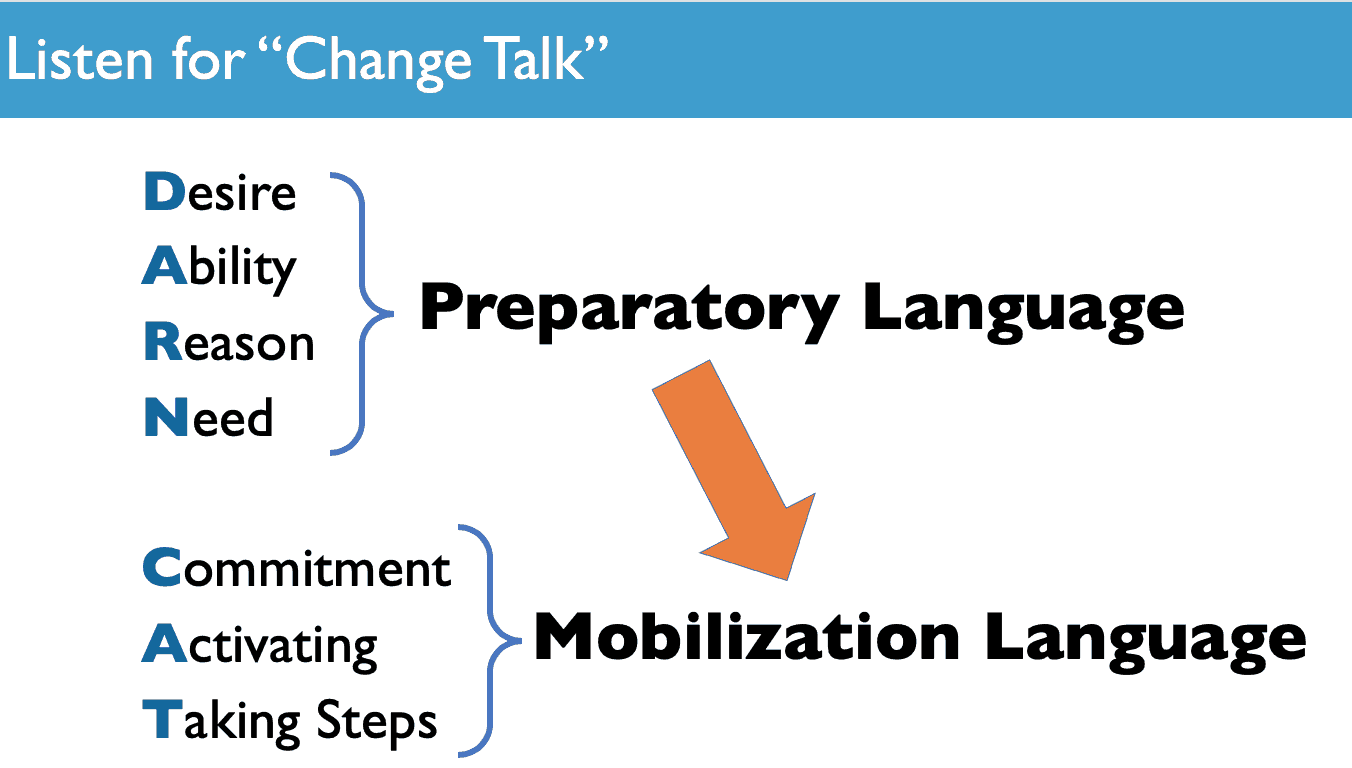

Maybe I need to respect their perspectives and their choices and do so in a way that's compassionate, empathetic. We want to listen for change talk as we're having conversations about change. We can look for what MI calls preparatory language. Desire to change, people talking about their ability to change, reasons for change, needs for change which are even stronger.

Then at some point, that moves into what's called mobilization language, getting closer to action, commitments, activating, which means I'm ready to take action. Then finally, taking steps. There is a mnemonic here, DARN CAT.

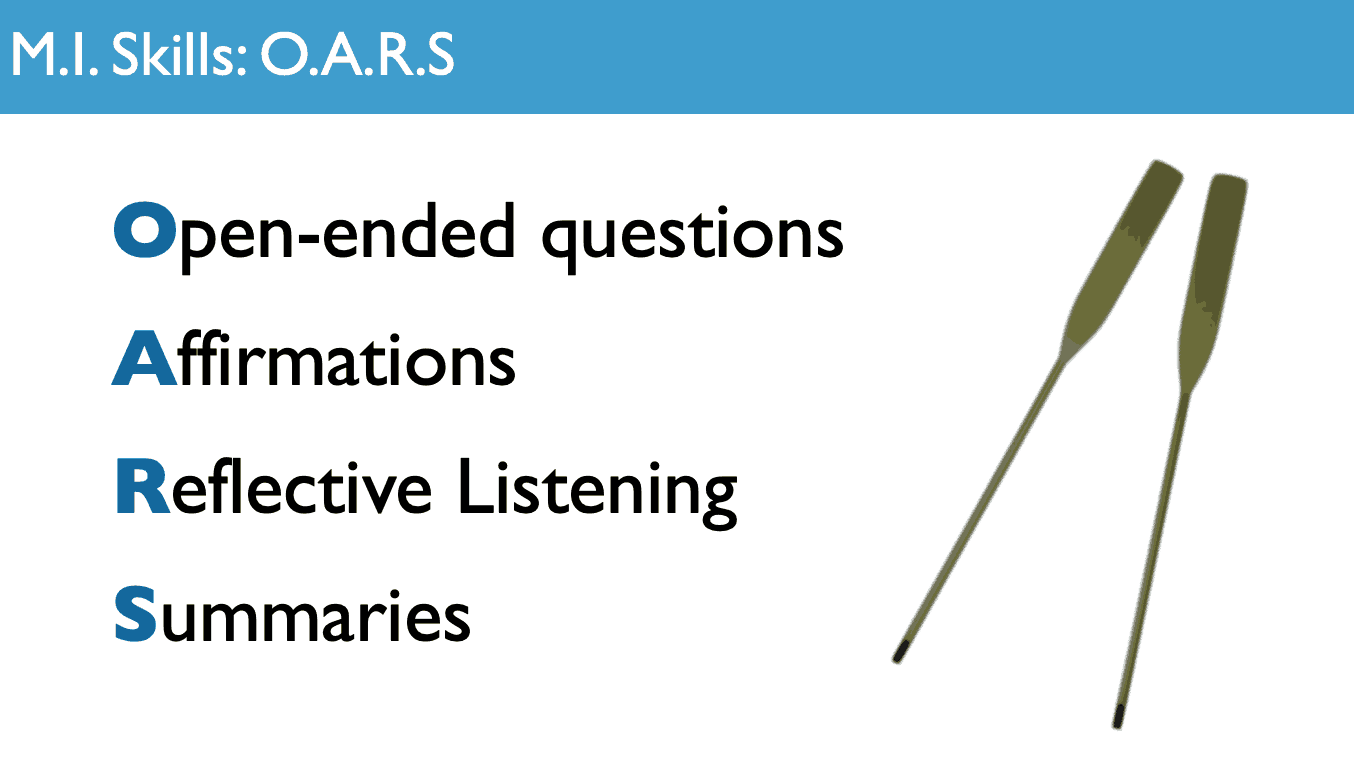

We want to hear more of this change talk and lead conversations in a way that encourages more and more change talk, because again, when that change talk outweighs the sustain talk, that's when people tend to take action toward change. There are skills in motivational interviewing. Here is another mnemonic, OARS, open-ended questions.

We hear a lot about this in Lean coaching. We want to lead by asking questions. We want to ask Socratic questions, and that's good. Motivational interviewing helps expand upon that. We can actually make statements that are helpful that aren't open-ended questions.

There is a time and a place for giving affirmations, giving reflections, building upon what someone has said through supportive statements and providing summaries of what you're hearing. People might say, “Yeah, but those people are just being resistant. You can spare me the psychology mumbo-jumbo. Those people, they hate change.”

They're being resistant. Motivational interviewing teaches us…This is the book I'd actually recommend as a first read “Motivational Interviewing For Leadership.” A book about applications in the workplace.

That resistance is too often a term that seems to treat a normal part of the change process as something pathological, without thinking about how we as leaders might be contributing to that issue.

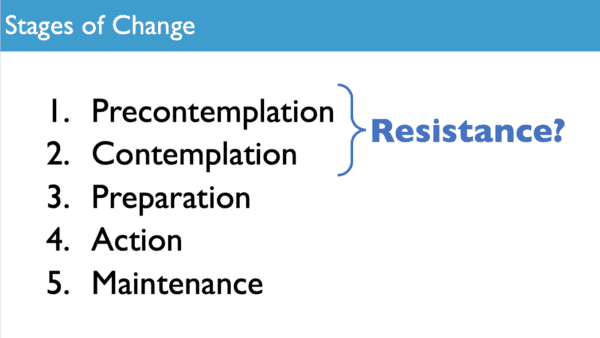

One of the key takeaways is to stop blaming others for being stuck in the process of change. There are stages of change. Change is a process, it's not an event.

Some of these things we might describe as resistance are a part of a process that we all naturally work through. My thought process of deciding I am going to floss before bed every day, or I am going to floss after every meal. There is that pre-contemplation. There is I'm not even aware of there being an issue.

There is contemplation, preparation, action, and then maintenance, which you might call sustainment. Instead of using the word resistance, motivationally interviewing provides a different word that might be a little bit more helpful. This word ambivalence. Is this just a softer way of saying the same thing?

Dillon's not resistant to change, he's just ambivalent. I think there is an important point there of realizing when someone is in that change process, when they're not yet taking action, they're on, as the psychologists say, they're on both sides of the fence. They want to change but they also have reasons not to.

The more we push and shove and try to force them to change, the more that other person is going to push back. It's a natural instinct.

If I were to say, “Adam, get up and move to a table in the back of the room.” You're looking at me like, “What? No. I'm not going to do that,” and you're right to do that. I didn't even try to pretend or articulate a reason for change. “Adam, what are your motivations for moving to the back of the room?”

This is not about making people do what we want them to do. This is not about manipulating people using clever psychological tactics. This is about engaging people and helping them move forward in changes that are in their best interest.

Just because a change is in someone's best interest doesn't mean it's easy to change. This is why people get caught in addictions. It's logical and rational that somebody should stop this addictive behavior, but it's difficult for people to do that.

In the workplace, there is a former Toyota leader, Ron Oslin who uses and trademarked an interesting phrase. He said,

“Leaders are people who aren't resistant to change. They are addicted to the status quo.”

What do we mean by addicted? The one clinical definition of addiction is actions that we take, even though we know they're harmful. But people feel trapped in that anyway.

I'd certainly point you to Ron. I've taken a day-long class with Ron. The Lean Enterprise Institute posted a webinar that Ron did. Again, he's a former Toyota leader who talks about how they taught these methods to managers at Toyota to help employees work through the change process.

When I heard him say that about a year ago, that was his big epiphany. I had never heard anybody from Toyota talk about this, the idea of counseling. Not just being a coach, but acting more like a counselor. When I think of my own ambivalence, change talk might include, and we'll struggle with this over the next two days, I need to stop playing with my phone. I should pay attention.

I want to be more respectful to people, but then, not in this exact setting, there might be sustain talk, “Well, I'm not needed in this meeting, anyway.” I might rationalize or excuse the bad behavior.

If I'm trying to help myself or if somebody is trying to help me with this, instead of just telling me or scolding me, “Put the phone away,” which might lead to some compliance, we'd have a conversation about, “Mark, what are your motivations for not playing with your phone so much when you should be paying attention?” That's a conversation.

When I think about writing my book. I struggled with this. I had change talk. “I need to write a book. I'm going to write it. I want to finish it. I will finish it.” That's change talk, but then there was also sustain talk, “Well, but I'm busy.” There's some fear, “What if I write it and people don't like it?”

The best way to alleviate that fear is to not publish the book and not take that chance, so I was caught in personal ambivalence. Even though I thought writing a book was a good, positive thing to do, we can't stop. One thing that was really helpful to me was not a licensed counselor per se, but a book coach.

As coaches, you have an appreciation for how a coach can help you and not just being the coach to others. One thing my book coach recommended and she hoped, with the writing process and motivation, she was someone I could talk to about fears and uncertainties about the book.

One thing she suggested to her authors, which reminds me of motivational interviewing, and this might seem corny as all get up… Jeff, don't judge me for my corniness. I created this document. I printed it out and I put it on my desk, this daily pledge. I'm not going to read the whole thing. I didn't just print this out and post it on the wall, because then it becomes wallpaper that we ignore and tune out.

But going through the process of saying these words out loud is a great lesson for motivational interviewing. This idea of not to change thoughts, but to change talk, that there's something in the connections of our brains when we say things out loud that are change talk, that activates our brain in a way that pushes us forward.

That's really helpful. This was helpful, of giving those reminders, talking about motivations and commitments that I was just making to myself to try to hold myself accountable. These ideas are helpful, thinking of your own motivations and ambivalence, but in the workplace it's more likely that we're trying to help others get past their own ambivalence.

One of the things we have to be careful about is what motivational interviewing calls the righting reflex and try to ignore or not fall into that trap. Motivational interviewing calls it the “righting reflex” is the desire to fix what seems wrong with people and to set them on a better course, relying in particular on directive.

“Mark, put your phone away.” That's directive. That creates pushback and I don't think it's because I'm uniquely oppositional. It's just as an equal and opposite reaction. You tell someone to do something, their brain immediately goes to why they don't have to or why they don't want to.

Triggering those thoughts may come out as talk about why they don't want to. That sustain talk actually hampers their progress in that change cycle. Rather than beating people up for being resistant, we shouldn't necessarily beat ourselves up for falling into this trap of the righting reflex. It is human nature to tell others what to do.

It's well-intended. You may have that other person's best interests at heart. It's well-intended. You're trying to be helpful, but the trap is it doesn't work or it's far less likely to work than this process of engaging people in their motivations.

A year ago, I was here in Austin at the Lean Coaching Summit and there was a really inspirational group up on the stage from a non-profit called Beyond Emancipation. You remember this group. They help kids who have aged out of a foster care system and are left on their own and they have a lot of struggles and they need a lot of help.

The woman from this organization was reflecting and she said,

“I spent eight years telling foster kids what to do and it was exhausting.”

She didn't frame it necessarily in the context of motivational interviewing, but I thought, “That sounds familiar.” It was well-intended.

There are non-profits full of loving, caring people who are trying to help others. Through their own process, they came to reflect and realize those well-intended behaviors weren't really helping the foster kids change, and that was their mission and their passion.

What does work is evoking people's motivations. I'll share some examples of this briefly. Guiding that conversation in a way and actually doing more listening than talking, you want to increase the amount of change talk that you hear and try to reduce or steer people away from their sustain talk if they're falling into that trap of talking themselves out of changing.

What they learned at Beyond Emancipation is this idea of evoking and drawing out from others. This sounds like Lean thinking to me.

We believe that the person that's closes to the problem is closest to the solution. This is respectful. It's proven to be effective.

I want to share an example from a workplace. There was a hospital manager that I was sent to go coach. This is a trap to be careful about. Somebody has to give you permission to coach them. You need to build some relationship since people are going to have their guard up.

I was asking some open-ended questions. What do you want to talk about? What are you trying to make progress on? She said, “I know I need to do these daily gemba walks and huddles,” and she said, “I'm stuck.” That makes me think of motivational interviewing.

She wasn't being resistant to Lean management practices. She was stuck in a state of ambivalence.

I could have stood there and said, “Well, you need to do that every day. This is proven to be effective, doing these daily gemba walks.” Telling, expert mode. That's probably not going to be helpful. It feels good. It's tempting. It's an instinct.

I heard change talk. She would say things like, “I need to do those huddles every day,” and so I might give an affirmation that says, “You're really trying. This means a lot to you.”

That's not an open-ended question, but it's a helpful statement that keeps her talking and maybe triggers more change talk, as opposed to the sustain talk, “I know I need to do this, but it's really hard to make time.”

We look for that change talk. If they're saying things like, “I want to do daily huddles.” “I could start doing daily huddles.” “If I do that, we'll improve more. There is a good reason.” If that leader is saying things like these, that leader is more likely to be getting closer to action. “I've got to engage my people more.”

Then there's mobilization. “I'm going to do this.” “I'm ready to start.” “I'm taking action.” Then there might be trouble with maintenance. There might be trouble with doing it every day.

Trying to keep out of the expert trap and the righting reflex, we want to encourage more change talk to shift that balance. When someone is stuck, there are a couple of really helpful questions.

I asked, this comes straight from motivational interviewing,

“On a scale of 0 to 10, with 10 being most important and zero being not at all important, how important is it for you to do those daily gemba walks and huddles?”

She might say, “Oh, six.” Classic stuck-in-the-middle. She knows it's important. She wants to do it. She needs to do it, but she's not always doing it.

Here is the follow-up question that's critical,

“Why did you say six instead of zero?” or “Why did you say six instead of three?”

You're always anchoring it back on the lower number. Here's the magic trick that happens. I shouldn't call it a magic trick. The important thing that happens is that follow-up question triggers change talk.

“Why did you say six instead of three?” “Well, because my people are really counting on me.” “We set an expectation that we should do those daily huddles…” She is articulating more and more change talk.

If you've asked, “Why did you say six instead of ten?” now you're triggering talk of barriers, obstacles, reasons not, excuses. You're inadvertently triggering sustain talk, which is proven to not help someone move up that curve of commitment.

Then there's the second question,

“On a scale of 0 to 10, how confident are you that you can make that change?”

These two things are important, commitment and confidence.

You may have somebody who's really highly committed to doing huddles. Maybe they say, “Well, my confidence is at two,” because maybe they're afraid they're not doing it right. That makes them afraid to go out, fail, struggle, or be embarrassed in front of their employees.

Asking that same follow-up question of, “Well, why do you say two instead of zero?” They'll give you little snippets of the positive, the change talk. You can build upon that by asking follow-up questions, open-ended questions, affirmations, reflections, summaries.

“Yeah, I don't feel confident. I don't feel very confident. I feel a two.” Then you can ask questions that try to continue that other person's process of talking themselves into change.

This idea, again, that being right doesn't mean others will go along with us. We talked about this yesterday in our change management workshop in a little bit different context. Organizations that struggle because they have the right solution, or the right idea, but people aren't buying into it. Or, some people aren't buying into it.

Instead of labeling them as bad people, we need to invest time and have those conversations. There is a lean expression that fits here, the idea of, “You need to go slow to go fast.”

Engaging people, evoking their motivations for change, helping them plan what they are going to do, that takes more time. Like the idea of going out and doing those huddles, gemba walks, and engaging people to speak up and implement their own ideas. That's more time consuming as well.

We can tell leaders, and here's the trap I try to avoid myself, to tell people they need to go and engage others. Maybe I should be engaging that leader in helping her come to the conclusion that she's going to go out and engage others.

Make sure we're not forcing bottom-up improvement in an implied top-down way. Again, that's human nature. We can try to fight human nature.

Do we want to be right, or do we want to help others change?

Again, as I've tried to share here, this is something I've reflected on, if not beaten myself up over at times of things I did in the past that maybe weren't helpful. It felt good in the moment. Maybe I'm addicted to telling others what they should do, beyond it being an instinct.

If we reframe resistance, talk about ambivalence, not expect that resistance could go away at the flick of a light switch, and think about ambivalence in moving people along, we can start conversations about change. We can practice. We can practice asking these questions. We can practice asking about people's motivations and get better at this as we go.

I'm trying to practice some of these methods and techniques, incorporating it into my own coaching and work with organizations. I'm going to make an offer. If you are feeling stuck, professionally about something you need to do, should be doing, want to be doing, but you feel like you're in that state of ambivalence where you see both sides, “I want to change, but I'm struggling with it.”

If you're on both sides of the fence, I'd be willing to do a phone call, a Web meeting, a video chat, or something where we can talk through this. In the spirit of trying to help you help yourself through this change process, maybe that might be mutually beneficial. There's a way you can schedule time with me online.

With that, I hope this is thought-provoking. That it wasn't off-putting in terms of telling you, you need to stop telling.

[laughter]

Mark: I was all too aware of that irony in that possible trap. Please forgive me for that because these are ideas I'm excited about. You have that tendency to go, “Hey, hey, Jeff, come to this workshop with me. Come watch this webinar.” You're like, “What, man? No, come on. I don't want to go.”

We'll talk about motivations some other time. Anyway, I hope this has been helpful. Thank you again for letting me talk.

[applause]

[music]

Please scroll down (or click) to post a comment. Connect with me on LinkedIn.

Let’s build a culture of continuous improvement and psychological safety—together. If you're a leader aiming for lasting change (not just more projects), I help organizations:

- Engage people at all levels in sustainable improvement

- Shift from fear of mistakes to learning from them

- Apply Lean thinking in practical, people-centered ways

Interested in coaching or a keynote talk? Let’s talk.

Join me for a Lean Healthcare Accelerator Trip to Japan! Learn More