Scroll down for how to subscribe, transcript, and more

Joining us for Episode #474 of the Lean Blog Interviews Podcast is Norbert Majerus. He has his own firm now but previously worked for Goodyear, joining the company in 1978 in his home country of Luxembourg. He moved to Akron in 1983 and worked disciplines in the Goodyear innovation centers in both locations, retiring in 2018.

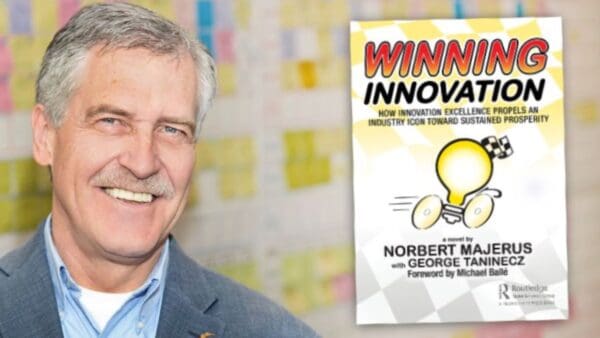

His first book (2016) Lean-Driven Innovation: Powering Product Development at The Goodyear Tire & Rubber Company was a Shingo Award recipient. His latest book is Winning Innovation: How Innovation Excellence Propels an Industry Icon Toward Sustained Prosperity.

In today's episode, we discuss Lean and innovation — how they co-exist, how Lean Product Development drives innovation, and how to truly engage people by leading with humility and respecting people.

Questions, Notes, and Highlights:

- What's your Lean origin story?

- Goodyear had tried Lean a few times in MFG – didn't work well — WHY?

- This was before Billy Taylor – they worked together 5 years

- Growing up on a farm — Toyota is said to be a company of farmers… how did Lean resonate with you?

- Lean is Lean? – doing this in unusual places, it's all the same

- Definitions? Innovation vs. improvement?

- Make sure we don't stifle creativity (we can all be creative, as Norm Bodek always said)

- Toyota and The Innovator's Dilemma

- Akio Toyoda stepping aside as CEO — a new push for EVs there?

- Can combine lean and innovation

- How best to connect “Respect for people” and “rapid problem solving and experimentation” for product development and innovation? Humility…

- Can you be innovative enough for long enough withOUT those lean culture concepts?

- Your new book is in a Business novel format – why write it this way?

- Norbert's website

The podcast is sponsored by Stiles Associates, now in its 30th year of business. They are the go-to Lean recruiting firm serving the manufacturing, private equity, and healthcare industries. Learn more.

This podcast is part of the #LeanCommunicators network.

Video of the Episode:

Thanks for listening or watching!

This podcast is part of the Lean Communicators network — check it out!

Automated Transcript (Not Guaranteed to be Defect Free)

Announcer (1s):

Welcome to the Lean Blog podcast. Visit our website www.leanblog.org. Now, here's your host, Mark Graban.

Mark Graban (12s):

Hi, it's Mark Graban here. Welcome to episode 474 of the podcast. It's May 3rd, 2023. Our guest today is Norbert Majerus. We're gonna learn more about him in a minute. We're gonna be talking about lean and innovation. So to learn more about Norbert his books and more, look for links in the show notes. Or you can go to leanblog.org/474. Hi everybody, welcome back to Lean Blog interviews. Our guest today is Norbert Majerus. He has his own consulting firm now, but he previously worked 40 years for Goodyear. He joined the company in 1978 in his home country of Luxembourg.

Mark Graban (54s):

He moved to Akron, Ohio in 1983 and worked with Goodyear Innovation Centers in both countries, retiring in 2018. His first book was released in 2016. It was titled Lean Driven Innovation, powering Product Development at the Goodyear Tire and Rubber Company. It was a recipient of the Shingo publication award, and his latest book, I'll Hold it up here for those who are watching, is Winning Innovation, how Innovation Excellence Propels an Industry icon towards sustained Prosperity. So congratulations on the shingle recognition and congratulations on Thank you. The second book.

Mark Graban (1m 34s):

How are you, Norbert?

Norbert Majerus (1m 35s):

Good. Pretty good. And thanks for inviting me to share my ideas here on your podcast. Yeah, appreciate that.

Mark Graban (1m 43s):

Yeah, thank you for being here. There's a lot to explore about innovation and lean and, and, and talking about the two books. But you know, first off, Nore as we, we like to do here, you know, everyone's got a unique story of how they were first introduced to Lean this or Toyota that. So what, you know, what would you say is your origin story related to all of this?

Norbert Majerus (2m 5s):

Well, I, at, I am a Six Sigma master black belt, and I have to say that I really enjoyed Six Sigma work. It's very scientific and, and we got a lot outta it. If you do it right, you can really, you get it really enjoyed. It can dig into deep problems and hide behind your computer. You don't have to worry about people too much and really enjoyed that. And then we got a new vice president and, and he said, yeah, I like what you do with, he said, but with Six Sigma, I said, but I, I wanna really push lean harder for product development and see.

Norbert Majerus (2m 54s):

And I said, no, no way. I said that I'm happy, I'm doing no way. And, but he didn't give up and I'm glad he didn't. And so he kept asking me a few more times, and then I was at the point I knew if I say no this time, he will not ask me again. And that's when I said yes. But there was one thing that I learned here. He really was committed to it. He wouldn't have asked me three times, and if he hadn't been extremely serious supporting lean in the Innovation Center. And as I said, it was, for me, it was a risk, it was something new that there, not a lot of people have been successful with it, but I'm really glad I did because it worked really, really well.

Norbert Majerus (3m 44s):

And, and why not? I mean, and we didn't have to invent anything new, by the way, it the same lean that thinking same lean principles, same lean people management that you would use in other areas. They worked fine for us. So yeah.

Mark Graban (4m 3s):

Was was that vice president new to Goodyear? Did they come in as an outsider, do you

Norbert Majerus (4m 8s):

Know? No, no. He actually came, he actually came from Luxembourg too, so we could speak on native language. His name is Jean Clark. I quote him a lot in, in my book. And he had been in Latin America, actually in Peru, and he learned lean there and especially in assimilation, and that he's a good thinker. He said, well, when he came in back to product development, why would this not work in the innovation center? And I, I really, I'm glad he have that.

Norbert Majerus (4m 48s):

It does work really, really well.

Mark Graban (4m 52s):

So why, why do, do you remember why you said no at first or why you were hesitant? I mean, was it a matter of all Six Sigma worked well enough for you? Or what, what what were you thinking then? Well,

Norbert Majerus (5m 5s):

I'm an engineer. Okay. And I, maybe I went into engineering because I didn't like to work with people. At least that, that did cross my mind. And I was happy if people left me alone with my computer. And the, so the, I I worked some really nice project with Six Sigma and really successful for on, on a global basis for the company. And why, why stop a good thing that, that was my first one. Number two, the company had tried lean a few times in manufacturing and it was not successful at all.

Norbert Majerus (5m 47s):

So I'm thinking by myself, man, that has such a negative, now connotation now that the experience isn't good. So why would I leave something that is a lot of fun to do something that, eh, it may not even work. Yeah. So those, that that was my main thinking. Yeah.

Mark Graban (6m 7s):

Well, I mean, that makes sense. I mean, even if we think of, you know, good lean problem solving models, if Lean was being presented as a solution, it's fair to ask, well, what's, what's the problem? What problem are we trying to solve? It sounds like you thought things were going well, right? Yeah, yeah. Now were you applying And I really, I mean, I did some green belt training. I'm not a six Sigma trained person. We don't talk about that a lot here, but it gives us an opportunity, you know, for me to ask, were you using Design for Six Sigma in that product development context?

Norbert Majerus (6m 45s):

Yeah, it, we were, that was one of my projects, yes. And it was about, and like, well, I don't wanna bore people with, with too many details here, but it, it was about performance of all over the United States in cold areas and in, in very hot states and so on. That was leading to a design for Six Sigma. But another very successful project was JD Power. A lot of people are familiar with JD Power and JD Power did a tire survey every year, and Goodyear was always coming in last in that survey.

Norbert Majerus (7m 29s):

And even though we had at that time the major market share, and there were questions asked, and the, our president at that time, Bob Keegan, met David Power in, in Detroit. And it was like, well, why is studio never winning it? And Bob Keegan says, well, I mean, that's not a good survey. My people tell me that, that it's not a very scientific survey. And so then Bob Keegan, then David Power says, well, that's what all the losers are, say. And of course, that Support, support and JD Power actually gave me many years worth of data.

Norbert Majerus (8m 14s):

So I had a very big database and I could do real statistics with it that like, I had enough data to come to, to hear conclusions. And then I went back to JD Power and I showed them, and I showed them some of the weaknesses and some of the good things, and they asked me for my recommendation, and I made the recommendation. And the next year we won the JD. Also have to say they did accept recommendation six Sigma can really work for you if you understand it and do it right. So,

Mark Graban (8m 51s):

So am I hearing you right that it was really a change to the JD Power methodology as opposed to change and how the tires were designed and manufactured?

Norbert Majerus (9m 1s):

Yeah. Well, of course it was more a change to their methodology because if we really, we did redesign the tires, okay. So don't get me wrong, but that would be four, five years until they appear in the, in the survey. And I didn't have time to wait that long. So, so I had a recommendation and it was a very good recommendation. It, it made the, the award much more appropriate, much better. And they accepted it. But I also knew when I made the recommendation what the results were, please, hey, yeah.

Mark Graban (9m 37s):

I mean that's

Norbert Majerus (9m 37s):

Real science apply to, to what, what, what they pay me to do at work, so,

Mark Graban (9m 46s):

Sure, sure. Now, you mentioned earlier this idea of Six Sigma was effective if you do it right. We could say the same thing about lean. I'm curious, I mean, you might not have been in the middle of this, but did you hear explanations for why, when you say Goodyear had tried lean in manufacturing, it didn't work Well, do you know, was it a matter of not doing it right? Not trying long enough? What, what did you hear? I

Norbert Majerus (10m 17s):

Mean, it's a very clear answer. I didn't understand it when I went to that plant the first time. But plant, they hired the best that they could get to the, with their knowledge about, about lead. The, the process they implemented was absolutely awesome. I I, I looked at it, I said, man, this is fantastic, but it didn't work. And you know why it didn't work. They did not engage the people. I didn't know it at that time. It was just like, Hey, do this, do this, do this and do that. And it was, it was a little bit of teaching, but it was just enough teaching that the people understood what they were supposed to do.

Norbert Majerus (11m 2s):

But it was not that, that was it. And there was one person who didn't even speak English very well. They needed a translator to, obviously came from Japan, had learned from the absolute best. And I, as I said, absolutely amazing what they knew what they did, but later I understood it didn't work because they didn't engage the people. They should have taught the people in the plant, work with the people in the plant, get them, let them deploy it and let them run it and so on, and coach them along.

Norbert Majerus (11m 43s):

That was the, the piece that was missing. And then I went back to other areas where it was also tried and didn't work so well, and exactly the same thing. Yeah. It was kinda, Hey, do this rather than how can we help you be successful with

Mark Graban (11m 60s):

This? Yeah. Yeah. I mean, you know, you, you mentioned earlier things including lean as a way to manage that this is consistent, whether it's healthcare even, or, or different types of environments. But, you know, I, I have seen and been around lean initiatives where it was basically some expert telling people how to rearrange all the equipment.

Norbert Majerus (12m 21s):

That's exactly, that's,

Mark Graban (12m 22s):

But that, that, that was, you know, what they did was probably correct, but insufficient, like you said, if the people didn't understand, if they barely understood why things were being arranged and rearranging equipment doesn't mean you're managing any differently.

Norbert Majerus (12m 37s):

Well, it did work for a while, really well, and it did, it worked as long as they were there managing it, but eventually it got over their head. There were four people, it got over their head and there was no owning if the system, nobody owned it. And the minute they left okay, a few months later, there wasn't much left of it. Of it. Yeah. And it, it, it, it didn't sustain itself. Absolutely not. Yeah.

Mark Graban (13m 9s):

Yeah. I mean, if you'll indulge me a quick General Motors story from 1995, you know, I came into a plant where somebody had designed, you had copied a design for a lean department, we're making cutting metal for engine blocks. And it was designed, but the idea of, okay, well it's going to flow, uptime's gonna be high. We are not going to buffer everywhere, meaning pull parts off, pull inventory off. It wasn't designed for that. But then before long, the people trying to run that new design, they have their old habits of saying, anytime a machine was down, we are gonna pull parts off and have piles of inventory everywhere. And they weren't doing the things, they weren't doing the preventive maintenance that would've kept the machines running.

Mark Graban (13m 53s):

And to me that was a very clear lesson in a mismatch between Yeah. How an area's designed to be quote unquote lean. But if you're not gonna run it that way, it could be even worse. It could perform worse than it was back, you know, previous generation.

Norbert Majerus (14m 11s):

Yeah. The other thing, by the way, that brings up another thought that was a big piece of it too. They put, they put lean on top of an MRP system. The, the, the factory was run by a computer and the accountants and everybody was counting on that system, and they needed it to keep running like that. Now you get your planning system from the computer and you wanna plug in the system on top of it. That only works again, if you engage everybody. And in this case, it would not have been only the factory workers to be engaged, but also the, the leadership, the all the different functions involved from purchasing to, to, to, to planning to, to finance.

Norbert Majerus (15m 1s):

And everybody had to really rethink that approach and become part of it, and then work together to make this work and integrate the pull into the MRP system. So

Mark Graban (15m 15s):

Yeah. Yeah, that's another great example of a mismatch in, you know, sort of adopting one practice being outta sync with other ways. Now, you know, when you talk about the first attempts with lean at Goodyear and not engaging people like this seems clearly before the time when Billy Taylor was rising through the ranks, because lean, it sounds like Goodyear because of Billy and others eventually figured it out. And Billy, I know is huge on engaging people. Did you ever, did you meet him and work with Billy?

Norbert Majerus (15m 44s):

Oh yeah, I, well, Billy, yes. We, we did, we spent about five years at least at Good Year working together where Billy, it didn't happen overnight either. So, but I have to give Billy great credit when he got the shingle award that everybody had actually asked, what is this? And they didn't even know what it was. And, and he had gotten the, the, the, the shingle award there. I mean, that was, and then Billy, you have to understand, he, he had to run many plan, but the plant that I'm talking about was one of Billy's plans, but not when this all the, the initiative was deployed there.

Norbert Majerus (16m 30s):

He, in her, he was put in charge of that plant later.

Mark Graban (16m 34s):

Okay.

Norbert Majerus (16m 35s):

Didn't happen on his shift.

Mark Graban (16m 37s):

Yeah. Yeah. So Norbert, I was looking, you know, at your bio and, and and beyond being born and raised in Luxembourg, it says in your bio that you were raised on a farm. And the reason I bring this up is, you know, Toyota is always said to be, you know, a fairly rural company, but they were farmers or come, you know, from farming community. Did I, you know, I'm curious from your perspective growing up on a farm, do you see where some of those mindsets of lean are kind of intuitive to a farmer as opposed to say a hunter?

Norbert Majerus (17m 12s):

Well, the one thing you learn on a farm, you have virtually no, no, no resources. Okay. You, you still have to make things work, and you become extremely resourceful. And, and that is something that the Toyota fathers of lean, I mean, they really had to make it work with what they had in, in Japan at that time to compete with. And I'm not, I'm not surprised that, that that's where they learned it. I mean, you really have no tools. You, you, your, your machine breaks. What are you gonna do?

Norbert Majerus (17m 52s):

You're gonna have to invent or become creative to, to, to keep it working because you have a day of sunshine and you have to get your, your crop in. And I think that resourcefulness and relying on the few resources that make the best outta those few resources is something that I'm not surprised that that's how it grew up. That's how it, that's how they developed that culture, I think. Yeah. Or that piece of the culture.

Mark Graban (18m 23s):

Yeah. And it sounds like with what you went and studied, and you, you probably didn't have any interest in taking over the farm, did you?

Norbert Majerus (18m 33s):

No. Well, that would've been very difficult because it happened to be a very small farm, and you, the farms of that size have no, had no chance at that time to survive in the global environment. I mean, Europe, all of a sudden you used to sell your goods to the people down the street, but now all of a sudden with European Union, now you compete with the p the farmers in France that have, that are hundred times bigger than, or the, the Northern German farm. So that, I mean, there was no, that future would've been very difficult.

Mark Graban (19m 11s):

Ok. Well, good. You've, so I wanted to ask you also, and on one level, you're talking about how lean is lean, but the principles are the same. Yeah. Coming to your books and using the word innovation, and in, in, in some settings we talk about improvement are, how, how big is the distinction between improvement and innovation? How, how do you think of those two words?

Norbert Majerus (19m 36s):

Well, every most improvement you can say is innovation. You, you can look at it that way, but the, the, the stretch that comes in with innovation, if it becomes disruptive and if it becomes disruptive, lean and disruptive don't always go together so well. But the principles, you can apply the same thing thinking even to disruptive innovation. It's just, if you understand the principles, you know, you know how it works. I was at a plant last year for the AME award, and I was amazed how innovative they were.

Norbert Majerus (20m 18s):

I was amazed how innovative the people were on the assembly line with, with the way they solved their problems there. They did not have a marketing strategy to implement the new product. I mean, that's done in the office, but the, their thinking was way out of the box and very creative. And they were also empowered to do those changes. And that's something that I gave the company a lot of credit for, because a lot of companies, they say, well, you can change as long as you don't do anything that, that, that rocks the boat here.

Norbert Majerus (21m 1s):

Right. But these people didn't. It was whatever they came up with, they give them a chance to try it. And it became very, very creative and became very effective, by the way, I stuff that I've not seen in another plan, that level of creativity. So it's not, it, it works everywhere.

Mark Graban (21m 25s):

So, so I mean, I'm, I'm, when you use the word creativity, it makes me think of Norman Bodak who passed away a couple of years ago. This podcast was his idea back in the day. He was, he was very creative. And you know, he emphasized, as you were talking about Norbert, how, how everybody has creativity, people in the factory floor, people in offices, people in the executive suites. We all have the ability to be creative. But a lot of companies stifle that creativity.

Norbert Majerus (21m 59s):

Yes, absolutely. Absolutely.

Mark Graban (22m 1s):

And then they wonder why aren't people being creative?

Norbert Majerus (22m 4s):

Absolutely. And by the way, I'm sorry.

Mark Graban (22m 7s):

No, go ahead. Go ahead.

Norbert Majerus (22m 8s):

Yeah. Was, that was one of the first books that I've ever read about. It really inspired me, by the way. Now give another experience with you. I, I came to, and I had done some creative work with, with airplane Tires, ok. Probably the last place where you, where you should take a risk. And I, I find myself in a meeting where the director, I didn't even know I up in the meeting and, but the, the, the meeting only had one purpose. The, the director wanted to make it very clear that that stuff like that will not be done on his shift.

Norbert Majerus (22m 53s):

And, and I got that message very, very clearly. And so did everybody else in the, in the, who was in the meeting got the message and people talked to each other and everybody that was very clear, Hey, we're not taking these kind risks. And I'm still, and I'm saying the airplane tires, they look the same now. Then they looked, they looked probably a hundred years ago or 50, 60, 70 years ago, and maybe that was the reason they still looked the, the same today. So that, that fear of, of risk and that fear of rocking the boat or anything is probably the biggest obstacle that, that companies have when it comes to, to innovation.

Mark Graban (23m 50s):

Yeah. So, you know, it's funny, it's interesting, Norbert you talk about this phrase disruptive innovation. We think of Clayton Christensen and the academics and the tech companies that are all like, excited about disruptive innovation. But if you are the disrupted now, now this, this be, it becomes scary or, or threatening. Did. And, and so that innovator's dilemma is Christensen. Oh

Norbert Majerus (24m 17s):

Yeah. Interesting

Mark Graban (24m 19s):

Fight. And Christensen called it. I mean, were, were you able to find ways within Goodyear or are you helping organizations now find ways to, to, to get past that trap?

Norbert Majerus (24m 31s):

Oh yes. Oh yes. In fact, the, right now the Tesla Toyota story, where the Toyota is criticized for not being far enough alone on electric vehicles, and I even understand they really, they did a reorganization and, and I also heard that some Tesla advisors are now working for Toyota. And, and that's good, a good, a good thing to do. And a lot of people say, Hey, maybe Toyota isn't what we all thought Toyota is. And I disagree with that because what happened Toyota to Toyota is exactly what Twisters wrote in his book about the innovator's dilemma.

Norbert Majerus (25m 16s):

The companies who are the best at doing what they are doing are the least likely to lead the disruptive innovation. Because Toyota has their process every so many years. They launch a perfect product. Tesla wasn't able to do that. Tesla launched a product and it wasn't so great. And they worked, they learned, and then they launched another one very quickly and they learned again. And they learned again. And, but it is this process that we are talking about here. This, some people call it agile or whatever, is quick experiments to, to learn.

Norbert Majerus (25m 56s):

Because innovation is about learning. The, the first part of it, and those quick learning cycles is actually Eric Ries wrote about that in his book, The Lean Startup. And that is a totally new aspect. The, the Lean startup, the, the Agile and all these tools developed by the computer industry, they did find its place into most companies now. And those are wonderful tools to overcome this, this, what you call it, this, to, to manage this risk that a lot of these bigger companies see.

Norbert Majerus (26m 38s):

The other problem, of course, and Christensen insist that very clearly, it's very difficult to do it as a big company. And a lot of big companies, what they try to do, they buy a, a smaller company to make them successful in a smaller market, or they spin off a company. Johnson & Johnson has done that very well, that there are ways to do it. And for me, it all comes back to the culture. It obviously wasn't in the Toyota culture, that piece, but I believe that it can be in most people's culture, companies can learn that. I worked for one that knew how to do it.

Norbert Majerus (27m 19s):

I taught, worked, know a lot of other companies like 3M, and I had the chance to go to Google once and really learn a lot about how they do it, company, this can be done. And I'm sure Toyota is on the way to learn it. And it, it, it certainly can be done. There's enough research only talking about twists and alone. There's a lot of research there that shows companies and teaches them how to do it. So I'm encouraging everybody to, to to to not only go for a lean culture, but for go for, but I call a lean culture of innovation.

Norbert Majerus (27m 59s):

You can combine those two, right? They're not, the one does not do any harm to the other. You can really run those in perfect synergy.

Mark Graban (28m 10s):

Yeah. So I mean, you know, thinking of Toyota again, I mean, you know, arguably Toyota did very innovative things with the Prius and hybrid technologies. They can innovate. But you know, I think back to Eric Ries and Steve Blank in these, you know, lean startup type methodologies, there's always the questions of, you know, can we build something and should we build something? And you know, Akio Toyoda as CEO, you know, was it, it made many comments publicly about, you know, not believing that an all electric strategy is really the right way to go. And he would, he's criticized for that.

Mark Graban (28m 51s):

And he's out of, he's, he is, you know, not go doing what most of the other major automakers are doing. But now that he's stepping aside as CEO, he made some comments recently about how his replacement is probably the better person to lead that charge, right? So it comes back to more of, you know, strategic intent. Where where are you directing the innovation? What does that seem fair to say?

Norbert Majerus (29m 18s):

Yeah, that is correct. But the innovation, you don't direct the innovation. The market directs the innovation. Fair enough. But when Toyota, the Prius and all those cars, they still went to the gas station to get gas. Ok. The Tesla cannot go to the gas station to get gas, even though here in Florida, you can now drive up when there are Tesla charging stations there. But that is the big difference. The other thing that, that place here is what's called the, the chasm in the innovation. Okay? The electric vehicle only came that far because the battery wasn't ready. Now you can say, okay, we just get out of it now.

Norbert Majerus (29m 59s):

Or you say, Hey, we keep this going because the battery, in case the battery develops, we have it and we can launch it. And that was a big kicker. And I think that was an, maybe you, you call it luck, maybe it's intuition, maybe it's foresight. That is something that good innovator says. And obviously Elon Musk had that foresight to, and the battery came to his aid. And, and so a big piece of it, again, it comes back to understanding innovation, all what is to it. Yeah. Including in this case that he took a break waiting for the, for the battery to come along.

Mark Graban (30m 45s):

Yeah. Well, and that, and that seems to be part of the challenge with innovation and the innovators dilemma, that the technology at first doesn't seem good enough to replace the old, I mean, General Motors was the first ele the ev one, you know, in the nineties, the first electric vehicle on the market, if I remember right, it only had a range of something like 50 miles. It certainly wasn't 300 miles plus. Okay. And Kodak was an early developer, if not the first developer of digital cameras.

Mark Graban (31m 25s):

And I'll tell you, when I, I did an internship at Kodak in 1998, the digital cameras were either extremely expensive for professionals, like $15,000, or they were toys that were really terrible. Like they, they really, the, the, the consumer digital cameras were very low resolution. And, and, and Kodak, I mean, they, they got caught behind the curve. And if they hadn't been really crushed by digital cameras, they would've been crushed by phones because, you know, the digital camera makers got caught up in different innovations. Right.

Norbert Majerus (32m 5s):

Well, Kodak actually, 1974 had the first working digital camera. And I have a picture of it because the person who developed it gave me the picture. Yeah. So they had the technology and, but then again, Bob Keegan joined Goodyear in the, in the nineties, and he was the vice president of the films division. And he wa he said, if you make 80% net profit on film, why would you even think about it? Right,

Mark Graban (32m 35s):

Right.

Norbert Majerus (32m 35s):

Doing anything else. And but he was already, he left Kodak when, when the writing was on the wall then. Yeah.

Mark Graban (32m 44s):

Yeah. And then, you know, one other comment, I mean, I don't wanna take too deep of a dive into Tesla, but back to your point about the ability to combine, you know, if you will, lean manufacturing with innovative products, my understanding as an outsider of, you know, part of the Tesla history is, you know, maybe a different innovator's trap where it's, it's said that Elon thought, well, of course I can create a better way to manufacture the cars. I don't need to learn from Toyota and the others who've come before me. And there's, you know, a long history there where it seems like, you know, to Toyota was an investor. It seemed like Toyota was trying to help. And then they ended up, you know, sort of parting ways.

Mark Graban (33m 25s):

And I mean, it's just, it's interesting. A lot of Tesla's problems have been on the production side. Yes. How much it's the unknowable thought experiment of how much more successful would they have been with, you know, the, the, the Toyota manufacturing model. Absolutely. That had lived, that had lived in that factory, you know, that's, that had gone from GM old thinking to new me Toyota thinking yes. To now Tesla. Hmm. Which is not Toyota thinking. So it's just

Norbert Majerus (33m 55s):

Interesting. Well, yeah. Everything that is knowledge, everything that is learned, everything that is best practices out there, I think you have to, to learn that or you going, or you'll be behind there. There's no doubt, there's no doubt about that. If there is. But if there is a best way to manufacture, cause and that is lean, that is the Toyota manufacturing system, then there's no reason not to do it. Because you can learn it, it's out there. You, you, you can learn it. And, but the same way, by the way, you can learn innovation, you can learn lean innovation, same way. I mean, there are best practices that you can learn from, and I'm sure Toyota will pick those up.

Mark Graban (34m 35s):

Yeah. It seems like, you know, there's a couple pieces here and you know, you emphasize these both in the book, there's the rapid problem solving and experimentation, whether we call that designed for Six Sigma or lean product development or agile product development. And then there's the piece, you know, it comes from Toyota language respect for people.

Norbert Majerus (34m 54s):

Yep.

Mark Graban (34m 55s):

So in, in, in your experience, you know, how, how do those two concepts best fit together when it comes to product development and innovation?

Norbert Majerus (35m 4s):

The, as I said, I, I went into engineering because I was uncomfortable dealing with people. But I have to say today that after I learned lean, I mean the, the, the typical management philosophy of, of lean, like the respect for people, the humble leadership and all those things, I, I really, this was an eye opener for me. I had gone to many classes, leadership classes, all kinds of, and yeah, ok. There was always a little bit that stuck.

Norbert Majerus (35m 44s):

But I have to tell you, the, the, the, the lean education was real eye-opener for me today. I would say I wish I had learned that earlier in my career. I would have had a totally different career. I'm not saying I'm an expert on people, but I'm comfortable, I'm very comfortable around people because that is the way I would've loved to do it. It wasn't the standard, it wasn't the encouraged, I would've loved to do it that way. That's really helping you with innovation. And I, I tell you the, it, it engaging the people is, is the best thing you can do to make them creative, to make them innovative, to, to, to, to encourage them to, to think out of the box.

Norbert Majerus (36m 30s):

And the the other thing that I, the, the, the humility, you, you don't give them solutions. You just help them find the best solutions that is as fundamental to creativity as anything you can, you can do. So for me, that is a really, really a great way of managing an innovation organization. And also, for example, I went through several of those innovation organizations where you are separate. I, that was my first experience, the skunkworks approach.

Norbert Majerus (37m 10s):

That was my first experience. And a lot of companies have an innovation office. They have an, that's not the way to do it. People ha it, it doesn't work that way. It only works when people work together. When they collaborate from the first minute of the idea, the, the, you get input from everybody and you build this thing together. Everything else takes too long. Nothing else you that, again, I learned that in Lee and it works fabulous when you apply it to, to innovation, whether you develop a new process or a new service or a new product, whatever.

Norbert Majerus (37m 55s):

So for me, the, the basic people management of, of lean does wonderful things for innovation. Yeah.

Mark Graban (38m 4s):

You're, you're making me think of what you described earlier where, you know, kind of forcing people to do certain lean things that might be successful for a while. And, but it doesn't, it doesn't last, it doesn't sustain. I mean it seems like there, there are companies we could point to where without that, that that respect for people without humility, without that level of engagement, they could be innovative for a while. But does that cut, does that catch up to them eventually? If you think of companies where, let's say, you know, pe people word gets around quickly that if you disagree with the, the c e o, you get fired.

Norbert Majerus (38m 44s):

Yes. I had that experience.

Mark Graban (38m 47s):

How long can a company like that continue to be innovative or being in innovative in spite of some of those cultural, I would call them problems.

Norbert Majerus (38m 58s):

The, the innovation in a case like that works when the person who dictates or makes the rules dictates to do the innovation. And I've seen that happen. And you, you, you sell it to the top and from the top comes down, do it. You can be very successful with innovation it, but it takes a long time and it takes an enormous effort because when it comes down from the top as an edict does not mean that everybody will do it and people will prove the top wrong more than prove them. Right. And it, the failure rates are very high that way, but also it takes forever.

Norbert Majerus (39m 43s):

And you can't do that anymore. Today. The changes in the market are, are so quick today, you really, the, the agility is, is really needed to be successful with it. And so people may think it takes longer if you engage people doing it than when you tell them. And that is wrong. Okay. It, it, it's a lot more efficient and faster if you engage people from the beginning. Cause it may be a little bit of more work at the beginning to get started, but once you get going, you go in the right direction and Yeah. And everybody pulls in, everybody the boat in the same direction, you know?

Mark Graban (40m 28s):

Yeah. But you know, you're, you're making me think of even the opportunity perhaps to engage the market, to engage your customer base in the adoption curve for a new technology. Because, you know, a couple of minutes ago, you, you made the good point that of course the market drives the direction the innovation should go. And you know, I, I think I remember Akio Toyoda making comments of, you know, not, not being convinced that everybody wants to buy an electric vehicle. Yeah. Or that, you know, and, and so there's this question of, I mean, you know, you're, you're forecasting years into the future. Toyota could have been right on that regard. They could at some point even catastrophically learn that they were as wrong as the Detroit automakers were wrong back in the day about people wanting big, huge, giant gas guzzlers.

Mark Graban (41m 20s):

You know, so Toyota's read on where the, the market is going. I mean, that, that's, that's a difficult strategic decision. Or then it comes back to the question, let me turn it back to you, of how, how, how agile can they be if they're gonna change direction and say, you know what, we do need to be all in on a electric-only strategy. How fast can they move?

Norbert Majerus (41m 45s):

Yeah. The, we have to go back to Christensen, and again, here on the, the Toyota's customers probably told them very clearly what they want. They want a car that gets better gas mileage, more comfort, and so on and so on and so on. Nobody told them I want an electric vehicle. Cuz people are smarter than that. They know they can't charge that, that that vehicle and and so on. And, and Henry for said, if I had asked the customers, they would've said we won pass the, so it goes back that far.

Norbert Majerus (42m 30s):

Jobs had, every time somebody came with a new idea, he said, show it to me. And somebody showed it to him and he said, how does this demo, how can we use this to convince the customer that this is better? And in order to do that, you just build a rough prototype of something and people say, oh, we didn't know this. And now you are talking, now you have something that you can move and you can move very fast. And that is again, comes in the startup and has been very popular. I used it a lot and it, it, and talking back with my colleagues at Goodyear, that what it always came down to, it was so simple and you show it to somebody and he said, oh, that is a great idea.

Norbert Majerus (43m 22s):

And, and that is the piece that, that was brought along with all these entrepreneurs, these lean startup that were successful with these lean startups. They didn't have money, right. They couldn't do research. The only thing they had is trial and error. And then they made that process very, very efficient. Yeah. And I think that's the, the where a lot of successful innovation is done that way nowadays.

Mark Graban (43m 53s):

Yeah. You know, and I, and I think just maybe one other brief exploration of the ev adoption challenge. So I mean there's maybe this question of convincing, showing customers where they, they should want to be going. But then, you know, there, you know, there, there, there's that whole question of charging and range and that, that might be harder to, that's harder to demo. You can sort of try to explain and Tesla, you know, innovated with their supercharger network to help address that. But yeah, that, that, that consumer behavior, that consumer habit is, can, can be difficult to steer in, in, in that direction.

Mark Graban (44m 33s):

Some are uniquely charismatic and convincing like Steve Jobs.

Norbert Majerus (44m 38s):

Yeah, yeah, yeah. Well let's be clear about that. Tesla did not go to the mass market, by the way. Tesla went to some niches. And one niche was enthusiasts, people who loved the electric vehicles and they used that market to develop the technology to develop everything else. And yes, the batteries helped. If not, they would've had to take a break again until, until the, the, the batteries are at the level. But then what I see right now is how aggressively they develop the charging capacity.

Norbert Majerus (45m 21s):

Cause that's what you need to go to the masses now. And that will happen. And I think they're very good at that. And that is also something that prioritization of the most critical thing at the, at the right time that a lot of companies don't know. And I could tell you dozens of stories from Goodyear about that, that hey, this will only work if, and I, there's, it's very clear Tesla would go to the mass market if the critical mass of charging stations is available and they know them. That's what they push right now. And that's the entry into the, into the mass, into the mass market.

Norbert Majerus (46m 5s):

And then of course if the, if the station's out there and they share them and Tesla's very good at the sharing, they may share 'em with Toyota vehicles or other vehicles, which then of course helps them. Yeah.

Mark Graban (46m 19s):

And I'm, I know that, you know, between the two books, a lot of stories either directly about Goodyear or maybe inspired by Goodyear and, and other companies. So again, the most recent book winning Innovation, it's, it's available now nor Madris who's been joining us here today. So this, this book is a, a business novel format. I'm curious if you can tell us a little bit, you know, the, the thought process around, you know, doing it in that format. Yeah,

Norbert Majerus (46m 48s):

That is very easy to answer. The, the more I learned about innovation, the more I about lean to start with, it's all about people. Okay. And the, if you talk about people, it's not just engineering and it's not all left brain. It, it's, it, it, there's a lot of right brain considerations that you have to bring in. There are emotions, there are frustrations, there is anger, there is all those kind of things. And I thought for a long time, how can I bring these in and, and make sure that people understand that part of a lead transformation.

Norbert Majerus (47m 38s):

And in those stories, I could put them in there. They come out and it's, it's real people doing it. And it, it gives people the courage, Hey, yes, I'm not the only one here. This happens to other people too, and there's a way to get around it and there's a way to deal with it. That was the, the main reason that I, I tried to, to set it up, to set it up like that. The most of the stories in the book really happened. They happened at work, but I couldn't put, I couldn't put the name the real to them or whatever, but most of them really happened like that at work.

Norbert Majerus (48m 22s):

So if they happened in my environment at work, they would happen to other people in their environment. And it's that idea that I wanted to, to communicate. I know it's a stretch and I purposely did not at the end say, okay, now you heard the stories and here I know the principles. I thought that was disrespectful to people. I want people to think. And if they think and they understand, I think they can come up with those principles on their own. I'm convinced. Yeah.

Mark Graban (48m 56s):

Have you, I mean, I mean the book's been out long enough, you getting feedback from early readers that they are taking away the principles that you expected them to. Or sometimes maybe they come up with an insight that's even that's different,

Norbert Majerus (49m 8s):

Better. Some people, the most important comment is I just read the book to the end. I wanted to know how the love story. Good, that makes you to the end. We got, we got what we wanted it, I got last week, there's actually, this is about a small company, the owner of the company, and I actually got the call from a gentleman, he owns his own company. He said, man, this is the great book. He said, I see myself doing this whole thing and I see how I can do things differently. Of course that, but many people should see themselves in it.

Norbert Majerus (49m 51s):

I'm actually in the book three times. I'm in there as a young engineer who cannot sell his ideas. I'm in there as a, as a leading a major transformation. And I'm in there as how I wish I would've been able to run an organization. So.

Mark Graban (50m 15s):

Well, Norbert, thank you for, for sharing your, your experiences and your insights in the books. Thank you for I, you know, doing the same thing today. I feel like we're just scratching the surface of all the, we could discuss and all the things that you could share with us. So I will put in the show notes, of course links to Nova's website, the book, the new book, winning Innovation, how Innovation Excellence Propels an Industry Icon towards Sustained Prosperity. There will be links also in the show notes to some other articles that, that Norbert has written for the Lean Enterprise Institute and, and others. So you can keep learning from Norbert.

Mark Graban (50m 57s):

But thank you to the listeners for joining us for this hour. And, and Norbert thank you for being here with us today.

Norbert Majerus (51m 3s):

Thanks for giving me the opportunity.

Mark Graban (51m 5s):

Well, thanks again to Norbert for being a great guest today and for the conversation. To learn more about him, his books, his website, and more, look for links in the show notes or go to lean blog.org/474.

Announcer (51m 18s):

Thanks for listening. This has been the Lean Blog podcast. For lean news and commentary updated daily, visit www.leanblog.org. If you have any questions or comments about this podcast, email Mark leanpodcast@gmail.com.

Please scroll down (or click) to post a comment. Connect with me on LinkedIn.

Let’s build a culture of continuous improvement and psychological safety—together. If you're a leader aiming for lasting change (not just more projects), I help organizations:

- Engage people at all levels in sustainable improvement

- Shift from fear of mistakes to learning from them

- Apply Lean thinking in practical, people-centered ways

Interested in coaching or a keynote talk? Let’s talk.

Join me for a Lean Healthcare Accelerator Trip to Japan! Learn More