tl;dr In this post, Mark Graban delves into the origins of a photo he frequently uses to discuss standardized work and workarounds in the Lean methodology. After years of using the image, he finally uncovers its background, attributing it to its original context. This revelation serves as a springboard for a deeper discussion on the importance and challenges of implementing standardized work and identifying workarounds in various settings.

There's been this mystery that's been hanging over my head for about 15 years. It's a mystery that's bothered me and maybe two other people in the world.

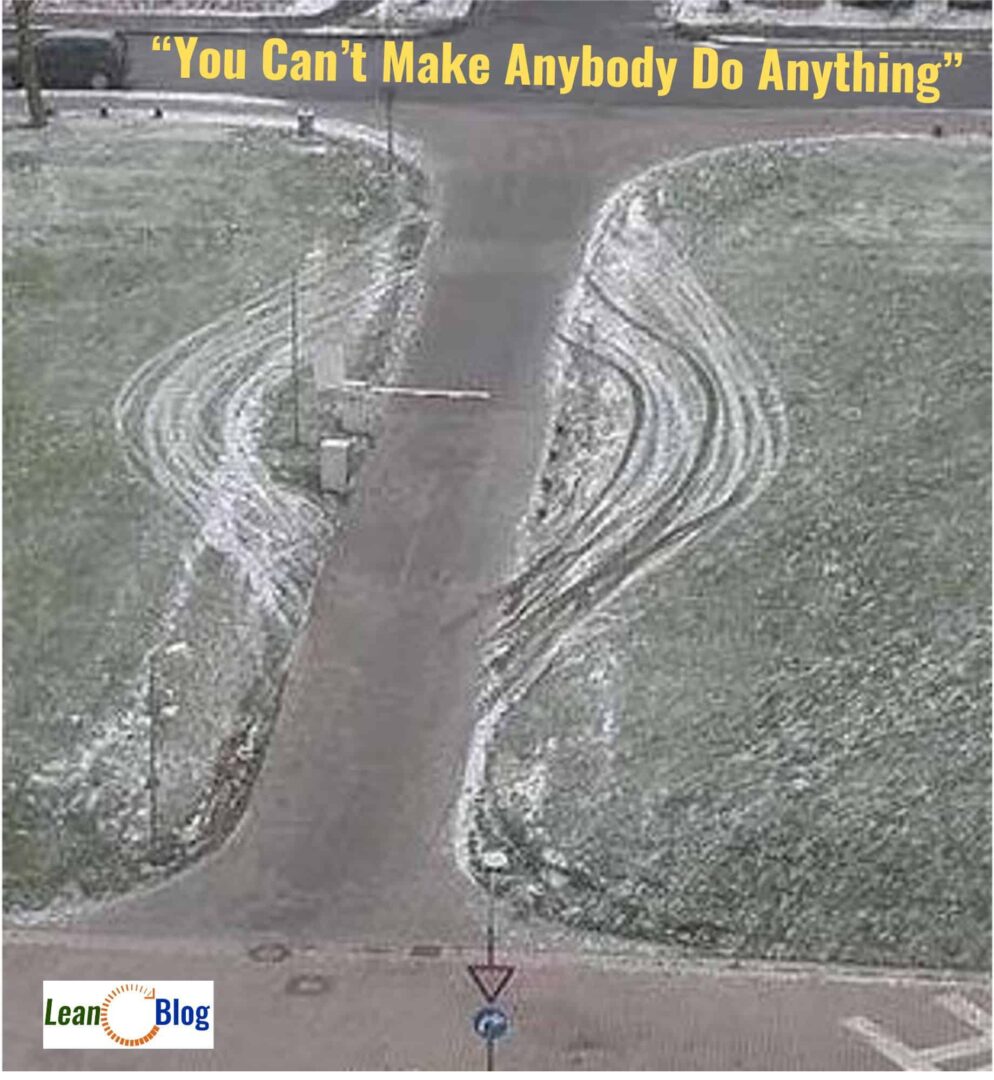

The mystery was the origin of the photo that's highlighted in this post. I was first given this image by a great hospital laboratory director who was a client of mine, as he was leading a Lean transformation in his department within a children's hospital.

This lab director had previously retired from a career in military medicine and was very learned and scholarly, as he was a student of fields including system dynamics and family systems theory (as applied to the workplace). He was a systems thinker and an enlightened servant leader, who Lean came pretty naturally to him, often just providing some common language for expressing concepts he long believed to be true.

Engaging the Team in Redesign and Continuous Improvement

One Toyota principle that he embraced while we were working to redesign the core laboratory was the idea that standardized work should be created by those who did the work. I led a dedicated “Lean Team” that was drawn from laboratory staff. They were the ones who analyzed the current state and they were the ones who proposed a new lab layout that would improve flow and turnaround times dramatically.

But transforming the lab for the sake of better performance wasn't just a matter of physical changes to the space. It was as much about changing the way work was done (standardized work), the way work was managed, and the way work was improved.

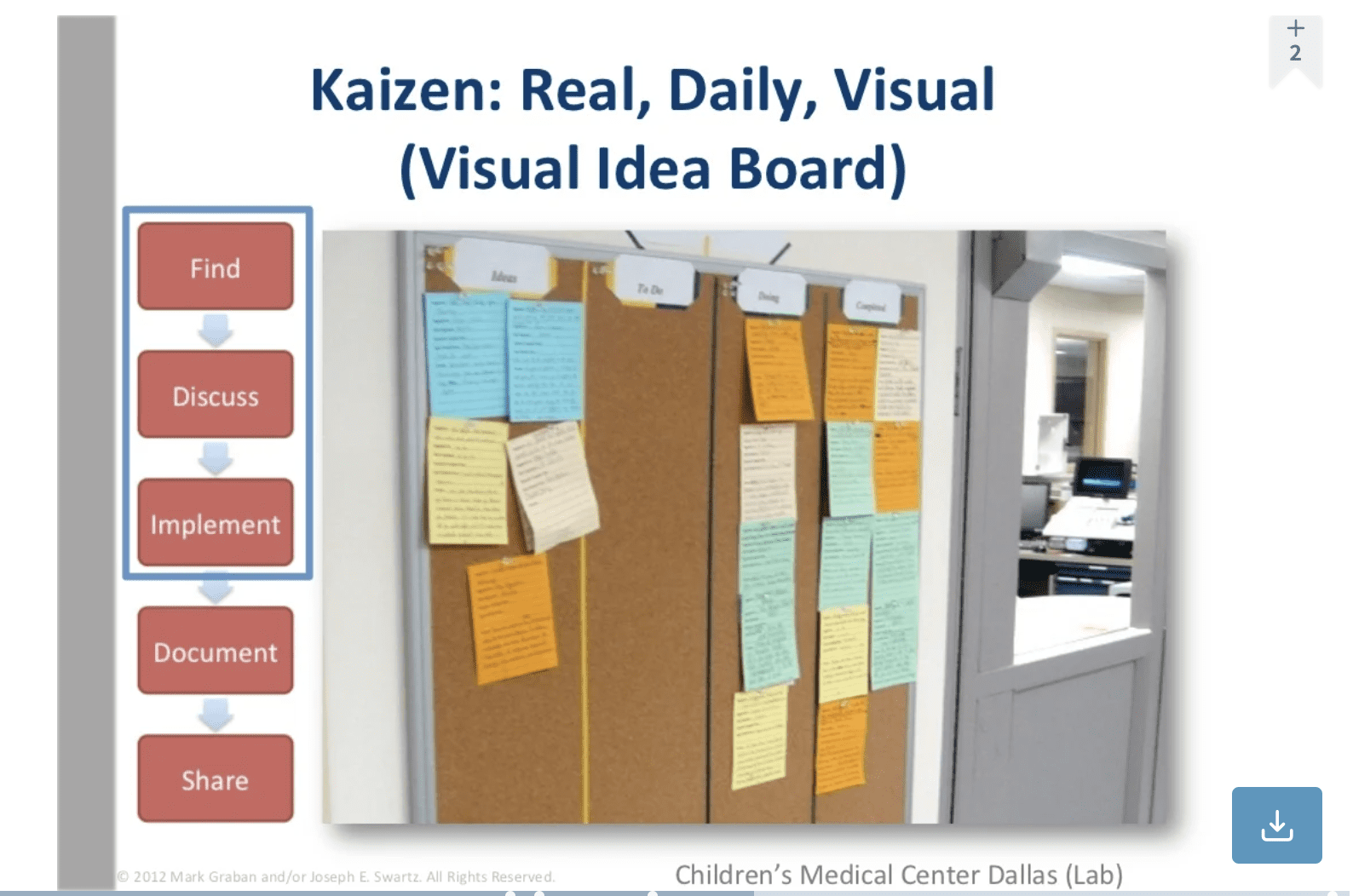

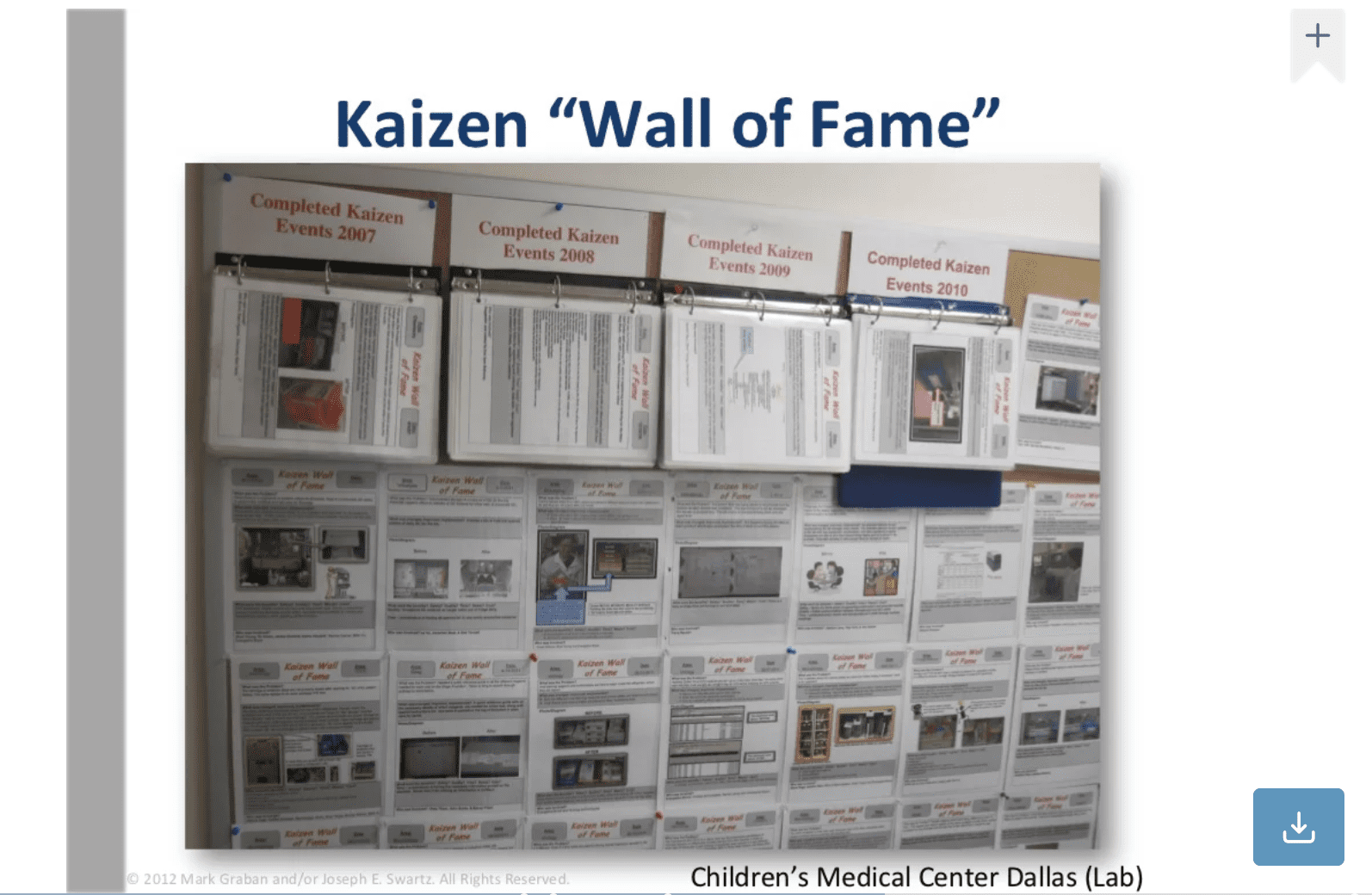

They became one of the best “Kaizen” style continuous cultures that I've ever seen in healthcare (and one of their Kaizen boards can be seen here in Slide 29 of this presentation that I gave and their recognition and sharing “wall of fame” can be seen in Slide 35. You can also learn more about this in my Healthcare Kaizen book series.

But, back, to the mystery image after these photos:

Managing Standardized Work

When the lab director, Jim, and I would talk about standardized work, we'd talk about:

- Writing standardized work documents

- Training employees on using the standardized work

- Supervising the standardized work

- Improving the standardized work

It was, to me, a properly holistic view of a standardized work system.

When it came to supervising standardized work, Jim wanted employees in the lab to internalize WHY work should be done a certain way. To me, that illustrated the “Respect for People” principle as well as anything.

He believed in making it EASY for people to do the right thing, which mean having the right support systems in place to make sure they had the right materials and supplies available, among other things.

Jim didn't want supervisors to be policing the workforce, looking for “violations” of standardized work. He wanted supervisors and managers to be supportive coaches. I agreed with him on all of that.

The Mystery Image and How I Learned About It

One day, Jim showed me this image and said something like, “You know, you can't really make anybody do anything.”

What Jim meant was that if employees are only following the standardized work because they FEAR getting in trouble… that's not sustainable. It's not sustainable because you can't be watching people like a hawk 24/7.

Jim wasn't bad mouthing the employees. He didn't think people were being “non-compliant.”

So back to this image — and I never thought to ask him the origin of it.

You see the road or driveway that has an access gate and its arm coming down to block the road.

But what's happening? Because of the snow on the grass, it's very visually apparent that people are just driving around the gate!

You can't make people use the access gate if they have an alternative that's easier.

So what should a Lean leader do when we see people driving around the gate? We should ask why. Why are people driving around the gate? We should assume people would be fine with doing the right thing if the right thing (staying on the road) were easy.

We should ask questions. We should go and see and investigate and talk to people. Here, with a photo, we can only speculate.

- Why are people driving around the gate?

- Is the gate broken?

- What makes the gate go up?

- If there are access cards or transponders, are they broken or too hard to get?

- Does the gate open too slowly?

- Does the gate work only work properly during certain hours, but people need to get through before or after those times?

We should think about our own workplace the same way. If we see “workarounds” (similar to the literal “drivearounds” that we see in the photo), we should ask questions and not blame people for employing a workaround. We need to understand what problem made the workaround necessary and we should eliminate that underlying cause.

Many of our workplace workarounds (especially in healthcare) don't leave such an obvious trail after the fact. We might need to work harder to see the workarounds in the moment. We should encourage people to speak up about the need for workarounds instead of just suffering through.

The Origin of the Photo — Discovered!

I had always wondered about where that picture was taken. From the road signs (and the snow) it might in Europe, since these clearly aren't American-style signs.

It wasn't that imporant of a mystery to me, as the image was still useful in presentations and when coaching leaders and prompting conversation.

I was really surprised to get an email out of blue back in July from Pedro Tenório, an MBA student in Brazil. I believe that he saw the image as part of some recorded “Lean Healthcare” education that I did for PUCRS Online.

He wrote this (and said it was OK to share with his name):

“Context and setting for the people driving around the gate:

I took a screenshot of the presentation, reverse image searched and found a wider picture:

It was apparently some kind of parking lot. Then I looked at the traffic signs and snow, and started searching for some snowy place: Europe? North America?

After a while, I've found it:

It's the University of Bielefeld (Germany).

They since have put some kind of post to avoid people driving around.”

Wow!

This image apparently gets used a lot by others, especially in the context of “driving around security gates” (or for analogies that people might create).

Here is a screenshot that shows the exact same location (taken from the opposite end of the driveway):

In Google Maps, you can move around and interact with the view (and I still don't know how Pedro found this within Google Maps, which is amazing).

When you zoom out in Google Maps, it looks like the gate is designed to allow people out to the street. The gate (as I'm guessing from the “Do Not Enter sign”) seems to be designed to keep people from getting in where they're supposed to be going out.

And that's probably why people were driving around the gate — they wanted to go the “wrong way” on a one-way driveway. I'm guessing that the gate opens automatically when you're trying to use it properly, to leave.

That's a question I had never thought to ask: “Is it a one-way driveway?” That's what happens when we don't “go and see” (in person or via Google Maps).

Now that we understand that it's a one-way driveway, we could ask questions like:

- Why are people wanting or needing to enter there?

- Are the correct entrances not convenient enough?

Or, you could start asking, “How do we prevent people from going wrong way?”

Countermeasures could include fences, but they chose these concrete posts (which are probably less expensive and easier to put in place).

So, that solves the mystery — or mysteries — of where the photo came from and why people were driving around the gate.

Thanks again, Pedro!

I sent him a Kindle copy of my book Measures of Success as a thank you.

Please scroll down (or click) to post a comment. Connect with me on LinkedIn.

Let’s work together to build a culture of continuous improvement and psychological safety. If you're a leader looking to create lasting change—not just projects—I help organizations:

- Engage people at all levels in sustainable improvement

- Shift from fear of mistakes to learning from them

- Apply Lean thinking in practical, people-centered ways

Interested in coaching or a keynote talk? Let’s start a conversation.

![When Was the Last Time a Leader Around You Admitted They Were Wrong? [Poll]](https://www.leanblog.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/07/Lean-Blog-Post-Cover-Image-2025-07-01T212509.843-238x178.jpg)

How can we make sure that while we encourage open communication and understanding why things are done, we also keep clear rules and processes to ensure everything runs smoothly and safely?