This is an article that I originally published on LinkedIn back in 2015. Has the error proofing been improved since then, between credit card websites and apps?

“Lean” is a business philosophy and management system that is most associated with building cars (the Toyota Production System, or TPS). Variants of Lean methodologies are used in various industries including healthcare, startups, government, and financial services. If we pay attention, it's not hard to find examples of Lean methods and mindsets in our everyday lives – or a lack thereof.

The idea of mistake proofing, sometimes called error proofing or “poka yoke” (in Japanese), is a core concept in the Lean approach. Mistake proofing has its roots in the early days of Toyota, when their core product was weaving looms, as pictured below at the Toyota Technology Museum.

Sakichi Toyoda invented a loom that stopped automatically when a break was detected in the thread. Stopping automatically meant less waste, as less defective cloth was produced, and it meant huge productivity gains, as one employee could oversee 30 or 50 machines instead of having to stand and stare at a single loom, watching for a break. That's just one example of how, with Lean, quality and productivity are two sides of the same coin.

This idea of built-in quality, or “jidoka,” is one of the two foundations of TPS (see their corporate website). And, the sale of that weaving loom patent helped fund Toyota's later entry into the auto industry, led by Sakichi's son, Kiichiro.

In modern-day Lean, mistake proofing can be technology or a device that physically prevents an error from occurring.

For example, your car's gas tank is mistake proofed, in that it's impossible to put diesel fuel in a vehicle that takes unleaded gas. The diesel pump nozzle is too large to insert into the gas tank opening. It is possible to put unleaded gas into a diesel vehicle, since that doesn't damage the engine as badly (according to my father, the automotive engineer). That's smart design that doesn't rely on drivers being careful to avoid a mixup. If the unleaded and diesel nozzles were the same size, we all know that mistakes would occur all the time and many regular engines would be damaged by diesel fuel.

Mistake proofing is not just a device; it's also a mindset. That mindset recognizes that humans make mistakes. Instead of lecturing people to be careful (or to somehow not get fatigued or distracted), Lean leaders make sure systems are designed to be robust – to prevent errors or to mitigate the effects of human error.

As Sir Liam Donaldson, former chief medical officer for the British National Health Service says:

“Human error is inevitable. We can never eliminate it.” We can eliminate problems in the system that make it more likely to happen.”

So how that does that relate to paying your credit card online?

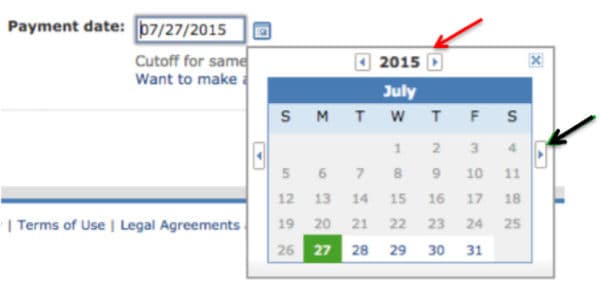

I went online to pay one of my personal credit cards the other day. On the screen where you select the payment amount and the date, you see the following interface if you click on the calendar icon:

The payment date was something like August 17th. There's a mistake waiting to happen on that website. If you don't look closely and end up clicking the first right arrow icon that you see as you look down (the one I'm pointing to with the red arrow), you'd change the month to July 2016 when most users would, at most, want to set the month as August 2015 to pay on time. You'd want to click the black arrow to advance to August 2015.

I've never made that particular mistake, scheduling a payment for 12 months into the future. About 15 years ago, however, I made an big error with online bill pay where I attempted to pay my cable company something like $10611 instead of $106.11 because I missed entering a decimal point. I didn't have that much in my checking account, so that created a huge mess that took a lot of effort to unwind. Oh, I long for the days of a $100 cable bill. But, I digress.

Taking steps to change my process to minimize errors, I started entering only whole number amounts for bills. For example, I'd round up to $107 to pay a bill of $106.11, carrying over a small balance for the next month. Currently, my recurring bills all go to my credit card, which saves me time and reduces the number of opportunities I'd have to make an error.

I wonder how often a credit card customer mistakenly schedules a payment for the next year? How many angry calls does that credit card company get each month from people who get hit with a late fee that results from scheduling the payment incorrectly?

I can hear some of you now. You're saying, “People should pay attention and slow down. I'm careful. I would never make that mistake.” You might think that, but the error is still possible, if not likely, even if you use the error prone interface every month. The Lean philosophy would drive us to design a system that makes errors less likely, if not impossible, because we recognize that humans aren't perfect and we can't expect them to be.

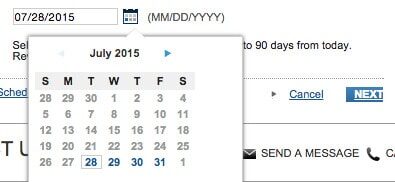

I checked my other two credit card companies and, sure enough, their interface is different… and better. I'd call them error proofed. One looks like this:

First off, this credit card company makes it easier for the user by defaulting to show the current month and the next month. That's it. There's no click required to advance months. It's impossible to mis-click to the wrong year or even to a future 2015 month that would result in a late payment.

Here's another bank's website that's also arguably error proofed:

This site only has one right arrow button, which advances to the next month. The “month advance” arrow is in the same location as the “year advance” arrow in the first example. That's an interesting inconsistency. The site's interface also indicates that it's programmed to not allow a payment to be scheduled more than “90 days from today.” A late payment is possible (and might, at times, be necessary for the customer, I suppose).

Many “Lean Startups” profess to follow Toyota's lead in practices such as root cause analysis (“the 5 whys”) and not blaming individuals for systemic errors. Hospitals have some examples of mistake proofing, such as standardizing anesthesia equipment to reduce the risk of a knob being turned the wrong way. Bar-coded wristbands and medication interaction alerts in Electronic Medical Record systems are examples of attempts at mistake proofing, although both of those methods have their flaws that still allow errors to occur. There are still major untapped opportunities to better mistake proof healthcare delivery.

Can you think of situations in your business, website, or hospital where you ask customers or employees to “be careful” instead of working together to mistake proof the work they do? Do you blame them for simple human error? How can we, instead, utilize mistake proofing, as a method and a mindset, to improve quality, safety, and performance?

Some 2022 Examples

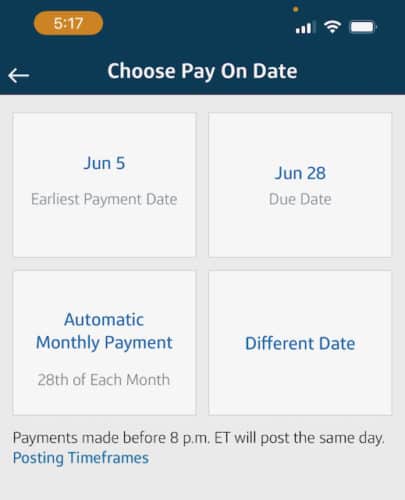

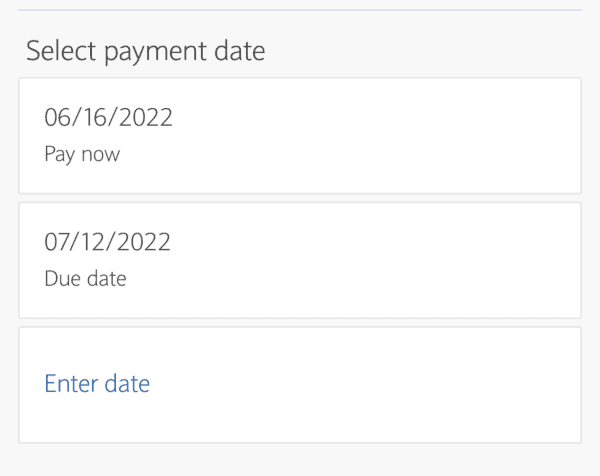

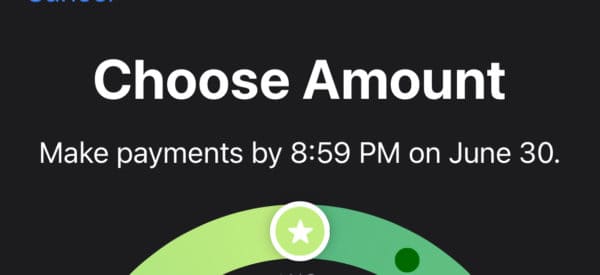

One of my credit cards has a much simpler interface that seems designed to let you pay on the due date instead of tricking you into paying late.

Way to go, Capital One. Nice job.

This is an interface that's good — making it super easy to choose “now” or “due date” or “other.” I bet most people choose “due date”:

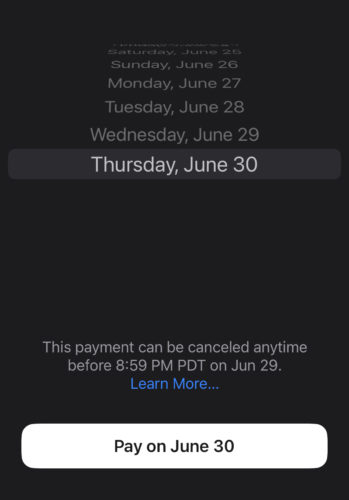

The Apple Card interface is also pretty good in that the scroll wheel stops at the due date and you can't scroll further. Although, that could be more clearly labeled as “due date.”

This is shown after the payment due screen that shows that amount shows the due date:

What do you think? Please scroll down (or click) to post a comment. Or please share the post with your thoughts on LinkedIn – and follow me or connect with me there.

Did you like this post? Make sure you don't miss a post or podcast — Subscribe to get notified about posts via email daily or weekly.

Check out my latest book, The Mistakes That Make Us: Cultivating a Culture of Learning and Innovation: