Scroll down for how to subscribe, transcript, and more

My guest for Episode #439 of the Lean Blog Interviews Podcast is Elliott Weiss, the Oliver Wight Professor Emeritus of Business Administration, having taught in the Technology and Operations Management area at Darden.

He is the author of numerous articles in the areas of production and operations management and has extensive consulting experience for both manufacturing and service companies in the areas of production scheduling, workflow management, logistics, lean conversions and total productive maintenance.

He's also a co-author of the book The Lean Anthology: A Practical Primer in Continual Improvement.

Before coming to Darden in 1987, Weiss was on the faculty of the Johnson Graduate School of Management at Cornell University. He has held visiting appointments at the Graduate School of Management and the University of Melbourne, Australia, and the Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania.

Elliott's degrees are all from the University of Pennsylvania:

- B.S., B.A., Math & Economics

- MS Operations Research

- MBA

- Ph.D., Operations Research

I reached out to Elliott to discuss his recent writing:

ON THE (BASKET)BALL: WHAT BUSINESS CAN LEARN FROM STEPH CURRY

He was writing about this excellent WSJ article:

Stephen Curry's Scientific Quest for the Perfect Shot

Here is my blog post on the topic, written after we had the conversation here.

Today, we discuss topics and questions including:

- Lean & operations origin story — what sparked your interest in this as a field?

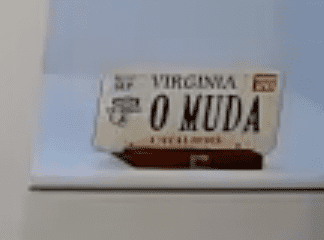

- The vanity plate? 0 MUDA — also had one NOMUDA

- Elimination of variation, enhancement of the wait, expectations management

- Lean applied to teaching? Research?

- Taguchi loss function?

- Is Curry reacting to noise?

- Hoshin Kanri — Application to retirement – mind/body/soul

- Book — “The Lean Anthology” case studies

- Chapter on using SPC charts to monitor blood sugar & diabetes

His license plate:

The podcast is sponsored by Stiles Associates, now in their 30th year of business. They are the go-to Lean recruiting firm serving the manufacturing, private equity, and healthcare industries. Learn more.

This podcast is part of the #LeanCommunicators network.

Video of the Episode:

Thanks for listening or watching!

This podcast is part of the Lean Communicators network — check it out!

Automated Transcript (Not Guaranteed to be Defect Free)

Announcer (2s):

Welcome to the Lean Blog Podcast. Visit our website www.deanblog.org. Now here's your host Mark Graban.

Mark Graban (13s):

Hi, welcome to the podcast. I'm Mark Graban. This is episode 439 it's February 9th, 2022. You're going to hear a lot more about them in a minute, but our guest today is Elliott Weiss. He is a professor emeritus of business administration at the Darden School of Business at the University of Virginia. So to learn more about Elliot and find links to everything we talk about in today's episode, you can look in the show notes or go to leanblog.org/439. As alway, thanks for listening. If this is your first time, please subscribe or follow in your favorite podcast app.

Mark Graban (53s):

Again, our guest is Elliott Weiss. He's the Oliver Wight professor emeritus of business administration, He teaches or was your, your I'll say welcome. I'll read the rest of your bio you're you're now retired. So past tense taught.

Elliott Weiss (1m 10s):

Yes. Although I'm still teaching now and then

Mark Graban (1m 12s):

Oh, okay. Well good. So has taught and we'll we'll hopefully continue teaching students in the technology and operations management area at the Darden Business School at the University of Virginia. Elliot is the author of numerous articles in the areas of production and operations management. He has extensive consulting experience for both manufacturing and service companies and areas, including production scheduling, workflow management, logistics, lean conversions, and total productive management. Before coming to Darden in 1987, Elliott was on the faculty of the Johnson Graduate School of Management at Cornell University. He has a BS and a BA in math and economics and the Ms.

Mark Graban (1m 55s):

And operations research and MBA, and a PhD all from the University of Pennsylvania, correct?

Elliott Weiss (2m 1s):

Yes. Go Quakers.

Mark Graban (2m 3s):

Yes. So I'm a PhD in operations research. So given all of the experiences and the teaching and there's, there's a lot we could dig into today. So Elliot again, thank you. Thank you for being here.

Elliott Weiss (2m 17s):

Thank you for having me, Mark. My pleasure.

Mark Graban (2m 21s):

Yeah, so I, I think it was an opportunity as I ask a lot of guests. I'm, I'm curious to hear your origin story of, you know, why operations research was your, your choice of fields and, and I see artifacts in your office related to lean. So I know that's important to you as well. So what's some of that origin story of how you got turned on to this whole field.

Elliott Weiss (2m 43s):

Sure. Again, mark, thanks for having me today. Way back when I was a math major undergrad University of Pennsylvania, and I hit a wall, I hit a wall in a field called algebra. You're not as good in math. I, this is great. I just couldn't see it anymore, but I always love to solve problems. And so I became more interested in applied math, came in, interested in operations with search the idea here that I could take my mathematical and my problem solving skills and work on them on interesting problems. So I moved over into the business school and got a degree in operations management and then worked actually started my work in healthcare way back when I did queuing models in healthcare for a maternity ward, looking at something called progressive patient care facilities.

Elliott Weiss (3m 39s):

So I became interested in capacity planning. Eventually I became interested in lean because I'm always looking for better ways to do things. So can I do things quicker? Can I do them better? Can I do them cheaper? And I quote here, bill gates, bill gates talks about two types of people. Actually four types of people you're either lazy or hardworking. You're smart, or you're not smart. And he liked the lazy smart people cause they looked for ways to do things better, to do things more efficiently. And I viewed myself as kind of a lazy, smart person.

Elliott Weiss (4m 20s):

I don't, don't like to spend a lot of time on non-value added activities unmuted as we know. So as I learned more and more about lean this idea of a waste reduction, my little sign behind me lean is the relentless pursuit. I don't even have it memorized, endless pursuit of creating value through the strategic elimination of waste. So that's that's for me. Let me look for ways to do that. Now I have four children and in a way it's supposed to curse and a blessing, this, this lean lens I have because I would all, when we're on vacation, we're out together, wherever the restaurant and amusement park, I always point out inefficiencies and things that could be kept cleaned out and they, they personal roll their eyes.

Elliott Weiss (5m 11s):

Whenever I do that and warm warms the father's heart here, my daughter actually became an industrial engineer from university of Michigan and she now does what I do even given all those eye-rolling, it's actually a lot of fun because she ends up teaching me now more than I no longer teach her.

Mark Graban (5m 34s):

Well, there's all sorts of process improvement opportunities in the world. And one thing I think we'll touch on later, you know, when we, you mentioned queuing models. So if you go to an amusement park, plenty of cues, sometimes those are masterfully manage. You go to different restaurants or grocery stores. You see all sorts of opportunities and questions around the structure of the queue and how could this be better? Yeah, it's a curse, right?

Elliott Weiss (6m 1s):

So, and in fact, when I go to Disney world, or when you go to Disney world Disney land, you often can tell the age of an attraction by the type of cue that they have. So one of the favorite attractions for children for kids, young kids is the dump Dumbo ride where you get to ride in this elephant. That's going up and down and up and down. But it's a classic batch process because what you have to do is it runs, it stops. They let all the people off and then the next people get on. So it's this rent, this big setup time. So you gotta run in batches and you wait forever.

Elliott Weiss (6m 43s):

And the kids just love it. I don't get it. But then my favorite ride is a ride called buzz light year. And buzz light year is actually continuous flow through, through the ride because the ride never stops. It's moving and you get to sit on a seat, you got to seat, but when you get up, you get up to the line, you get on a moving walkway. You're the walkway gets, becomes the same speed as the ride. You sit on the ride and then did you ride your chute? Excuse me, for being a little bit crazy here. And then yet at the end of the ride, you stand up, there's a moving walkway and you get off.

Elliott Weiss (7m 25s):

And then there's a little buffer space of empty seats for the next people to get on. So it never stops. There's no setup. You get the Disney likes that because Disney doesn't want you waiting in line because they want you out in the park. So you're buying souvenirs and meals and things like that, and you're not enjoying it. So, so a wonderful, wonderful example for me of line management.

Mark Graban (7m 49s):

Yeah. Well, it's interesting to think of yeah. Continuous flow in entertainment. Like I think of a traditional Ferris wheel, you know, would stop to let you off and let someone else on. And that, so then the, the revolution is a little bit herky jerky where I don't know if you've had a chance to go to one of these newer, really large Ferris wheels like the London eye or there's one in Las Vegas. There's one in Orlando where it's, it's really, truly continuously revolving. And you know, you've got these big pods that are large enough and the speed is slow enough that unless somebody has accessibility mobility issues, of course they'll stop it if need be. But you know, it's, it's like getting off of an elevator and getting back on an elevator where the, the attraction keeps going.

Mark Graban (8m 36s):

So you think that would keep the line at least progressing and moving, moving along. So, but yeah, hopefully you don't get too frustrated and shake your fist at some of these attractions that are well-designed Well, and then just touch on one queuing ideal. Let's see if I remember my queuing theory education, right? If you have a multi-server model, let's say a fast food restaurant, that's got four registers for people taking orders. Is it pretty universally more efficient to have one queue feeding all four servers as opposed to separate queues?

Elliott Weiss (9m 19s):

Never say never, never say always for the most part that that's true. And the idea is you're a, I could be technical part of your audience. I'm sure it's technical that there's a central limit theorem going on here. So there's a reduction of variability, but kind of pooling the resources. So if you're like me and you go to the supermarket, when, when you're in the supermarket, you always get behind the person who is looking for their money. Here has a price check. And meanwhile, the other lines are going faster, but here by having the snake line, the people behind that are not as not affected because I can kind of skip, skip, skip over that.

Mark Graban (10m 5s):

Let's do your best. You do your best to choose the line that you think is going to move along. And sometimes it's that person with a few, a smaller number of items in the cart that then ends up taking longer than the other line. But it's funny to see a mix. Sometimes there's a group of grocery stores in Texas central market and the, the, the main registers have individual cues. The express checkouts have that single queue feeding into like eight express lines, which seems to make it even more Expressy.

Elliott Weiss (10m 36s):

So, so the reason reason for that mark is the following. And I've never, although I've never been in a, on a army base or air force Navy base in their PX, they actually have a single line for all of the supermarkets. But the key issue there is for that self-help one, the time for me to go from the front of the line to the next one is short. Whereas with my cart, it's a long way to go to the next, the next checkout counter. And given the, that the card is three or four feet long, that single line going through snaking through the supermarket gives the impression to being exceeding.

Elliott Weiss (11m 26s):

I have another example for you though, of lean in the supermarket. And I use this for as an example for Smith for a single minute exchange. And I, and if I could plug my book at this time, lean thought is actually a story in that book as well. So think of your you're in the supermarket and you're behind the person and the person in front of that person has just finished checking out. And the clerk says that's going to be $187 and 30 cents. And at that point, the person in front of you takes out their checkbook and starts writing the check. So they're the beginning of writing.

Elliott Weiss (12m 7s):

The check is a setup time, regardless of what the amount was. It takes the same amount of time and regardless of how, how big the order was. So why can't I change that to an external setup time? And I always get, sorry, I always get internal and external, mixed up the words aren't intuitive to me, but let me set it up while the cork is running up and running the checking through the items, then fill out the amount. So I've reduced the setup time,

Mark Graban (12m 41s):

Right? Yeah, I think that's correct. Yeah. The external, that would be external up time, you know, I think in that scenario, but yeah, if, if, if so I try not to get in line behind someone who's writing a check. Cause that does seem like a slower cycle time. But yeah, I don't know. The store would almost have an interest in brown if everyone was paying by check, you know, rounding the prices to numbers that were easier to write out long hand, just to write 100 instead of 104, I don't know, but they don't want to give away the $4. Nevermind.

Elliott Weiss (13m 15s):

Another example of that, I have lots of examples of this. There's a, a, a fast food restaurant chain in Southwest Virginia and Northeast Tennessee called Pal's sudden service pal. Yes. Friends. And what they do is when you pay, if you pay with cash, they have drive through only if you give them coins, they don't even bother counting it. They just throw it in, you know, so if they're off a couple of cents or whatever, it doesn't matter. And they, the other thing that they do is they take the order and they don't take payment when they take the order that they take payment.

Elliott Weiss (13m 57s):

When you actually pick up the food and they'll have the coins ready for you, that they think that they anticipate again, trying to reduce some of the cycle time. And they're so effective that they actually get a car through the drive through one every 17 seconds. Oh my gosh.

Mark Graban (14m 16s):

Wow. That is sudden.

Elliott Weiss (14m 20s):

And the guy who runs it, he says, you know, we're not a, we're not a services, we're a manufacturing business. So they have a limited menu. They have they've five S the service station where they're making, you know, the mustard and the ketchup and the hamburgers. So it's really a great example.

Mark Graban (14m 41s):

Yeah. And, you know, people, people listening might say, well, you know, the, the lean principles or lean philosophy would say, well, we shouldn't have acute, but that is a reality of many service settings. And there are lessons I would encourage people to, to, to learn about queuing theory and incorporate that. I mean, one, I think very visible example of managing a queue, the fast food restaurants, two of them that come to mind Chick-fil-A in, in and out. Well, both actually, instead of having the fixed distance between the ordering box and the window, when the queue is longer, they'll, they'll put people outside and they'll actually kind of do kind of a mobile ordering.

Mark Graban (15m 25s):

I assume they're trying to match the, the, the, the time, the flow time of how long it's going to take to prepare the food and how long it's going to take the vehicle to then get to the window. And they seem to manage that pretty dynamically.

Elliott Weiss (15m 38s):

The other thing they might might be doing there is there's a whole science of waiting, waiting lines and active waiting is, seems shorter than inactive waiting. So here, the idea being that I think that I'm getting served already. So the service encounter has started becomes, becomes important here. So I actually have a model for, for this,

Mark Graban (16m 7s):

Sorry, before the model, when that, so there's this phrase that I love balking the queue. Like if somebody has an interaction earlier on, they're probably more, they're probably less likely to Bock the queue and give up if they've already ordered as opposed to waiting to order. So that's, that seems like smart business to

Elliott Weiss (16m 26s):

That's exactly. Right. So two, two things here. First, let's go back to lean and think of a manufacturing process with Kanban. So you have combat, so you have this inventory was essentially a queue, and I need that queue because I need that queue to buffer variability, whether it's set up time, whether it's a defect, whether it's, well, I don't have not every manufacturing process. Every time takes exactly the amount of time. So some are faster, some are slower. So I use this queue to keep my bottleneck fed. So, yeah. So I need, need that queue when I can't remove the variability completely.

Elliott Weiss (17m 6s):

So, so the model, I have a, it's called three ease. So three words that begin with E there's elimination enhancement and managing expectations. So first thing I do is try to eliminate eliminate the variability. So can I schedule things so I can go to the barbershop where I don't know how many people are coming and how many are going to be there, or I could schedule an appointment and presumably that'll reduce, reduce the queue. We could enhance the wait. So this is the idea of somebody playing a piano in the bank for people who still go to banks or the classic story of a waiting for an elevator.

Elliott Weiss (17m 54s):

So people were complaining about the wait for this elevator and apartment building. It's going to cost a fortune to add another elevator. What do they do? They put a mirror elevator lobby, because now all of a sudden there's an occupied. One of the little psychological rules is occupied. Time seems shorter than unoccupied time. So I'm occupied, you know, fixing my shirt, my tie, looking at myself. So it's there, or I manage expectations. So again, back to Disney world, and Disney is like the master of align management. There's always signs that say, this is how much longer to the ride. And they always overestimate what it is again, because the idea here is expected.

Elliott Weiss (18m 40s):

Weight is seem shorter than unexpectedly. Explain, wait.

Mark Graban (18m 45s):

And Disney does a lot to try to entertain people during the wait. So back to your

Elliott Weiss (18m 51s):

Enhancement. That's exactly right.

Mark Graban (18m 52s):

And the, and they lost people that actually actually schedule times on some of the rides. I believe that there's some like premium ticketing. I haven't been to Disney in a long.

Elliott Weiss (19m 2s):

Yeah. So there's something called a fast pass where I can go and schedule actually, you know, another great example of this was I saw this first in Harry Potter land. Whereas again, there, there, you have little hearts that you said in tools like the buzz light year, you can choose to go with your friends and ride. So three or four sitting there. But when I do three, when I, if it holds four, but only three people arrive, I have all this empty capacity. So if I don't care who I'm sitting with, I could get in a shorter line and be a partner with those three, be the fourth person again to, I have this bottleneck clump, the ride.

Elliott Weiss (19m 48s):

I have a long line having empty seats on the bottleneck. Oh my gosh, it's horrible. How can I fill that up? We'll fill that up by having these lo or having the customers who don't care, who they sit with. Fill that up.

Mark Graban (20m 7s):

I, I be curious when you're talking about people occupying themselves, whether it's a mirror or nowadays, almost everybody is carrying around a phone as a, keep yourself occupied device. I'd be curious if there's research, you know, if people are less dissatisfied with cues, because they're using that time to look at Facebook or to play a game or to do something, I

Elliott Weiss (20m 31s):

I'd be curious if I were still an active researcher, it might be a project I've worked on.

Mark Graban (20m 37s):

Yeah. But then you have the, the dynamic of, let's say you're in the drive through line at Starbucks and people are occupying themselves with their phone and they don't notice if the queue is advanced

Elliott Weiss (20m 48s):

Happens.

Mark Graban (20m 49s):

So well, speaking of cars and, and wanting to make sure I didn't forget asking me about one of the other artifacts in your office, for those who are just listening to the podcast, won't see this, there's a vanity plate behind you. I'll, I'll let you explain re re read the plate. And I'd love to hear the story behind it.

Elliott Weiss (21m 5s):

The plate says zero Moda. And actually my that's no longer in the car. Cause I sold that car. The other car has one that says no Moda. And so my life is about zero mood or no mood. I'm trying to get rid of as much waste as possible. So we got those vanity plates. Now my wife, when she hears me talk about a reduction of Moda and particularly something like five S so when I taught five S our MBA program, I often gave the students a project. They had to go 5s something. And she says to me, you know, you can talk about that all you want, but never show anybody our basement, Because it's one of these things mark, you and I were talking about earlier, before the podcast, the difference between knowing and doing so, I know I should 5s that, but doing it is something completely different.

Mark Graban (22m 4s):

Well, recently there was a big, long profile of Larry cult. Who's now the CEO at GE. He had been at Dana her for a long time, great lean company. And in that profile, I blogged about it really good article. But in the article, he made reference to something about not doing lean at home. And like, at some point you've got to just draw the line. Now I've heard, sometimes people get in trouble where there was so many of the families trying to quote unquote 5s, somebody else's domain. Right? So like in my home, I do a lot of the cooking. I do most of the cooking. So if my wife were to come in and organize things, I would be, it would be disorienting.

Mark Graban (22m 50s):

And if somebody were, if your wife were to come and rearrange your desk there, and there are important lessons there about, don't do this to somebody, make sure you engage them and make sure the motivation is there. Elliot, if you don't have the motivation to find faster basements, opiate.

Elliott Weiss (23m 7s):

Yeah. But you, you bring up a good, good point here, mark. And indeed it kind of mirrors my career. As I reflect back on it, I started out as a numbers guy. I was a mathematical model, two big mathematical program, queuing models, scheduling models. And as you said, my degree was operations research. As I evolved, I now do operations management, not industrial engineering theory stuff. And what we like to say, or what I like to say is it's the people stupid. It's not the people. It's the people stupid that what counts is how I am, how I apply this, how I implemented.

Elliott Weiss (23m 52s):

It's all about change management. You know this as well as anybody, it's not the best model. In fact, go, go back to Larry copes. I quote a lot. And I quote him incorrectly. He, he either said lean is a common sense, vigorously applied, or he said, lean is common sense, rigorously applied. So I say lean is common sense, vigorously and rigorously applying, but a colleague of mine, fellow by name Austin, English. So he gives me a quote from mark Twain and he says, mark Twain said, common sense. Ain't common until someone points, right?

Elliott Weiss (24m 35s):

So it all, it all goes, you know, there's leadership. And I guess there is something called followership, but how do I get people engaged in this? Because otherwise I'm doing something to them. So as opposed to them doing it for themselves, you know, you're, you're a consultant. You're your biggest job is asking the right questions so that people can figure things out for themselves. Rather than you tell that to them. At the Darden school, we do the case methods, Socratic method. It's the same thing. I have to figure out the questions to ask so that they can discover something that's meaningful to them.

Mark Graban (25m 13s):

Well, and I think that's also increasingly the leadership style and organizations of, of, of leaders not coming in and having the answers, but asking questions, listening, facilitating, guiding it's, it's, that's a different approach, not just for those of us who are outside consultants.

Elliott Weiss (25m 32s):

So, so mark, let me ask you a question, because the hardest thing for me is when I quote unquote know the answer, and I really just want to tell somebody the answer and no, but I, I got to pull back and pull back and say, no, I can't. W w what do you do in that situation?

Mark Graban (25m 53s):

It's, it's tough. You got, you know, get better at controlling the impulse to blurt out the answer, or, you know, I've had opportunity. Well, I would say I started my career very much as a numbers guy. I think, you know, my, my interest in people in business led me to industrial engineering, as opposed to other other branches of engineering. But I working in healthcare, I've had opportunity to be exposed to ideas that come from counseling and psychology. And I've interviewed some people, some experts about this on the podcast.

Mark Graban (26m 32s):

There's a field of counseling, a style of counseling called motivational interviewing. And the one thing they teach in that approach is as, as a counselor, as a coach, as a parent or whatever, you have to stifle what they call the writing reflex, you know, R I G H T I N G. So if we were to ever feel bad or beat ourselves up for that way, I think it's helpful to remind ourselves. It is very much a human nature reflex to try to be helpful. And, and one way to be helpful is to tell someone, I'm going to just tell you it be easier to, if I just tell you, it'll be safer if I just tell you, and, and that stifles development, and yeah.

Mark Graban (27m 15s):

So you just have to try to kind of try to fight that urge and remind yourself, ask questions.

Elliott Weiss (27m 21s):

So some stories there. So I have one son who's now in a master's program in a couples counseling, psychological thing, and often get together as a family. And he'll start asking questions. And it's like, I feel like I'm being analyzed. I really don't like it. Then my daughter who's, I said was the industrial engineer. He does this stuff for living. We did a take your dad to work one day. She, she works in healthcare and we went around. And so we're talking with the head of surgery, the head of the ER, talking about their problems. And the end of the day they, she says to me, you know, dad, you're not supposed to tell them the answers because I was in academic mode trying to show how much, how smart I was and saying, well, did you ever think about this?

Elliott Weiss (28m 13s):

Do you ever think about this? Or, you know, this is what you ought to be doing here. And she said that that's not what we do. We're we're coaching. It's like, oh, geez. She was so right. But it's hard for me to do

Mark Graban (28m 27s):

So. I, it, it is hard. Sometimes the coach needs a coach to, to point out, Hey, give me honest about this, or yeah. One of the ask, one other question is kind of reflecting on, on your career and being driven to try to eliminate waste. I mean, did you find ways to apply lean principles either to your teaching or to research methods? Like, you know, thinking of the work you do as a professor?

Elliott Weiss (28m 59s):

So the answer's yes. The thing that both I, and all my colleagues hate the most is grading. The grading is just, you know, it's one of these things where Jesus had seen it almost be parade or optimal. I hate grading my students getting grades. Why didn't we do it? It must add value for somewhere, someone

Mark Graban (29m 26s):

Who is the customer of the grade point average.

Elliott Weiss (29m 30s):

So, you know, I might have a, a semester where I'm teaching two sections of, well, I just, my very last one was teaching two sections of our Ember program, 75 people each. So 150 gray exams to grade, and I have two weeks to grade them. It's like, if there's a big batch of stuff. So the question is, how can I lean that out? And what I found, what I could do is I also go for single piece flow there. So single piece flow, meaning as the exams came in, I would grade them. So I don't have to do one 50 at once. Now. It turns out that a third of them come in the last day anyway, because it's not like they're sitting with a blue book and I'll do an at the same time.

Elliott Weiss (30m 17s):

So I still have that big batch, but it makes it much, much more palatable for me. The other thing I did mark was I had a Kanban board for all my projects. So each day, and the Kanban board was something like had five or six different sections. One section was ideas. So these are things I wanted to work, work on. And then I had something called doing stage one, doing stage two, waiting for response and finished. So as I would work on projects, the little cards would move along and I could see where I was working or what I was working on, what needed to be done.

Elliott Weiss (31m 0s):

I wouldn't start a new project until an old project was finished. So I didn't want, you know, the whole idea be con Kanban behind the board is give me a visual representation and limit the amount of work in process. So that would help me limit the work, the process. The other thing it did was it enabled me to go to co-authors for example, and say, Hey, this is overdue. You promised me this January 10th, here it is January 14th. Where is it? So that was empowering for me. And what, what I, if I did it well, every morning I would go in and have a three minute standup meeting with myself, kind of look at the board.

Elliott Weiss (31m 46s):

What am I going to work on today? What's the, what are the due dates? What's the important, important stuff. So it helped me PRI prioritize things.

Mark Graban (31m 55s):

Yeah, well, there are opportunities for improvement in any, any setting. And so that brings me finally to, well, not the final thing we'll talk about, but finally, the, the, the one thing that we originally intended to talk about is more from the realm of sports and Steph Curry from the golden state warriors I had read. And I'll, I'll link to this in the show notes. Maybe some of our morning reading routines are similar, but there was an article in the wall street journal about how Steph Curry was trying to perfect his shot. And then Elliot had written about this and sent me a link to what he wrote. And I thought, Hey, let's, let's talk about that.

Mark Graban (32m 36s):

And other things in a podcast. So we've, we've had a lot of the other things talk, but D D so w what Elliot wrote is what business can learn from Steph Curry. And then there was a subheading not far into it, continuous improvement and the perfect swish. Okay. Can I ask you to kind of touch on some of the key points of how Steph Curry is working to improve?

Elliott Weiss (33m 2s):

Sure, sure. So, yeah, mark, we both read that same article, which is what motivated my peace and your reading your stuff. Well, I see your book measures for success in the back there. You know, we talk a lot about not reacting to noise and looking for assignable causes, looking at accuracy and precision. And as I read the original article, I said, this is exactly what Steph Curry's doing. So the quote that I think he asked in that article was he wants to swish the swish.

Elliott Weiss (33m 42s):

So there's again for the technical people in the audience to go, it goes way back to Gucci and to goosey to Gucci's loss function way back when the idea here is it's more than just good or bad there's degrees of goodness and degrees of badness. So I could be within spec and get my three points, which is what the Curry's doing aiming for, but it can be off center. And what Carrie is trying to do is say, no, I want to be precise and accurate, get it right in the middle every single time. So we, we talk about action based on data, facts and analysis.

Elliott Weiss (34m 23s):

So given the current science data collection, what they can do with him is when he's practicing, he gets a, there's a speaker that goes on that tells them how far off center he is, so he can adjust his shot to get more and more centered, get more and more consistent. And the word we we use is get, make his process more robust. So by robust, if he's tight and in the center, if he's off one way or the other, he may be what we would call out of control in a data sense, but he's not out of spec. So his capability process capability is really high going back to our six Sigma training.

Elliott Weiss (35m 8s):

So really what he's discovered that he doesn't know is he's discovered his six Sigma analysis. And again, this idea, boy, I re more robust my process. Again, meaning that the Mo even in the, even when there's lots of variability around whether now a field goal kicker would be different, we would worry about Augusta wind or rain or something like that. He's indoors, but maybe the air conditioner's blowing one way, or he talks in the article about being tired at the end of the game or the fan noise distracting him. So what he wants is even of that affects his shot.

Elliott Weiss (35m 52s):

Still still goes in a hyper Seattle.

Mark Graban (35m 55s):

If you, if his natural shot, if his natural shot has a tighter variation around center, then he's more robust to some of those effects. You mentioned field goal kickers and thinking first basketball shot, you know, a shot that's off centered can still go in. But I imagine there's a function of the likelihood of being good decreases as you get. Off-center, you're more likely to hit the rim and it's not going to bounce, or what have you, but it was field goal kickers. I've used the goalpost as a way of illustrating the two Gucci loss function, because, you know, in American football, of course, anything that's inside, those goalposts is equally worth three points on a field goal.

Mark Graban (36m 45s):

It would be a different game. If you had now with technology, you could have, you know, sort of laser lines and you could award four points for a field goal that was very close to center, which would change the game and change the approach. But it seems like there might be opportunity, a similar thing for kickers looking at, you know, their, their motion is a repeatable process. And can they reduce the variation in their motion, which would then translate into less variation in either the placement of the football or the placement of the basketball. It seems like there's all kinds of opportunities there.

Elliott Weiss (37m 23s):

Well, I think when you're in football, for what I understand, the there's also, there's more variability there. Cause you have three people involved. You have the person who's hiking, the mall, the person who's holding the ball. And then the kicker, the quote, unquote six Sigma snackers long snappers will have the same number of rotations each time and have the, the laces in exactly the right place consistent. Yeah. So again, we talked about standard work, so what's the standard work that can, can produce that. Now, when I read the Curry article though, I worry. And it goes back to your measures of success.

Elliott Weiss (38m 6s):

Is he overreacting sometimes to what's just general noise. So, you know, he has a release angle and they'll have a amount of force go. We go back, I'm sure you've done the stat upload exercise with the export exercise,

Mark Graban (38m 23s):

The funnel exercise.

Elliott Weiss (38m 26s):

So again, here there's some there's, there's going to be some inherent variability and he gets this sound in the back minus two, plus two off. Yeah. Some of that he shouldn't react, right? Because there was no assignable cost. So the question is, is he actually adding variability by doing that reaction?

Mark Graban (38m 47s):

Well, Deming's lessons from the final experiment would say yes, if, if, if the feedback is like minus two to the left, and then he immediately reacts to, to the right, that increases the variation of dropping marbles from a funnel or the status bolt or whatever thing you might use. I mean, I think back to my days of manufacturing, we would have specifications for engine parts. You know, the size, for example, the diameter of a cylinder bore in the engine block. Well, there was a spec, no smaller than this, no bigger than that. But then there was also a nominal center.

Mark Graban (39m 27s):

And one of the biggest challenges and biggest fights with management is, you know, we would have engineers and frontline workers doing statistical process control on the center, like trying to switch the center of the basket, the center of the spec and something would drift out of control, which was a sign of the process now is maybe on its way to becoming out of spec and management top management at the plant would say, no, don't stop the line. It's still inspect. Those parts are good. Ignoring the idea that they're not equally good. And you know what, what's the, the quote unquote tolerance stack up of these different parts and you think, well, no wonder we were trying to catch up to some of the Japanese competitors that would have had much more focus on not just being in spec, but taking the Steph Curry view of being in the middle and not constantly adjusting the machine of like, oh, this one was, you know, 47 microns bigger than the center line of the spec.

Mark Graban (40m 27s):

That didn't mean adjust it by 47 microns at some point to your point, Elliott. Yeah. Just let the thing run if it's in control and the process capability is good enough.

Elliott Weiss (40m 38s):

So, so for me, again, going back to my teaching, I had a two by two matrix in control out of control in, out of, so what you've just described as something that is out of control, but inspect, and the question is, what do you do with that? I always called that living dangerously. So when it says I'm making good stuff, but I really don't understand this process. So I got, gotta be careful about,

Mark Graban (41m 4s):

And where are we defining quality as well? It passed the gauge, meaning it was good and it could move on versus what's the impact to the customer in the life and the use of that engine. And there, in this case it was Cadillacs, right? So this is supposed to be a premium engine and they, they weren't all perfect out in the field. And I think some of that was certainly due to living dangerously as you call it.

Elliott Weiss (41m 30s):

Yep. Now the other thing of course with Curry is use that as an example of a customer, your requirements change over time. So here you have Curry who's at the top of his game and he's worried about the game changing. So he has to become even better. But one of my students pointed out when he read that article was in fact Curry changed the game. So he was the one who made the, who raised the bar, so to speak. So the other people have to follow him and he knows how to do this. And other people are going to have to learn how to do that if they want to compete

Mark Graban (42m 9s):

Well. And we've talked about, you know, being, you know, mathematically minded people, I mean, you know, analytics and what's been learned in, in recent years, the idea over-generalizing a little bit, but the idea of the only shots you really ever want to take in a basketball game are a three-point shot or a layup or a dunk, because the expected value of those shots is so much higher than the shots in between.

Elliott Weiss (42m 37s):

Exactly. Right now, John Thompson, may he rest in peace? The former coach at Georgetown complained vehemently about that. At least when the three-point shot first came out, it's almost like your laser example for the kicker. He argued, you should get more points for a closer in shot because those are harder to get. And somebody chucking it out from the outside,

Mark Graban (43m 0s):

Like a shot that's more contested.

Elliott Weiss (43m 2s):

Yeah. More contested yet a higher probability of making it once I get it, but harder to work it inside to do that. Yeah.

Mark Graban (43m 11s):

And it's essentially any talking about how the game has changed and the expectations of players. I just pulled up some stats. He's, he's, he's never played in Philly, but Brook Lopez from the NBA seven feet, I think he's probably seven. What is he? He's seven feet tall. So as a center, the expectations, the voice of the customer, his first eight years in the league, he rarely ever took a three point shot, like zero per game or 0.1 per game. And then suddenly in the 2016/2017 season, he started taking five, three point shots. Again, he had to evolve his game and it actually makes them at, you know, probably typically league average percentage.

Mark Graban (43m 56s):

But yeah, there's all kinds of lessons there related to our work and our career of you've got to make sure you evolve or otherwise end up irrelevant. There are some tall centers in the NBA who never play anymore because they can't shoot three.

Elliott Weiss (44m 11s):

Well, think of again, you know, I'm a Philadelphia sports fan, so I'm going to go back to our, our, her sass guard or former guard, Ben Simmons, who never learned how to take a shot, you know?

Mark Graban (44m 27s):

Yeah. And that that's for somebody who has so many talents and was drafted so high and is paid so much, it's almost a mental block. It seems so well. And, but I think there's a lot to be learned from, you know, whether it's, you know, the analytics or the continuous improvement or the leadership aspects of sports and, and think about applications back to our workplace. I mean, you've written other articles. It seems like there's a shared interest here and, and trying to extract what, what lessons are interesting points are there from the sports world. Is there anything else that, that comes to mind from recent years related to operations or lean

Elliott Weiss (45m 13s):

And sports and not off the top of my mind, other than going back to what we talked about before and the leadership that's involved, you know, basketball, particularly being a team sport, getting out of these five guys to work together, although at the end of the game, it seems like you want that one person who can take the ball to the basket and score.

Mark Graban (45m 39s):

Yeah. So one of the things, one of the ask you about, I mean, maybe we can do another episode at some point, not to take advantage of your retirement, hopefully increase the time availability, but maybe, maybe you'll be open to that at some point. But speaking of retirement, and speaking of beginning of the year, this is a time when people organizations are often reflecting about the previous year, they're planning ahead. And one thing that, that you teach is Hoshin Kanri or strategy deployment, whatever words we want to use. I, when, when we chatted before the recording, you mentioned that you apply these concepts to looking in, into your retirement.

Mark Graban (46m 22s):

Can, can you tell us about that?

Elliott Weiss (46m 24s):

Sure. So, you know, our mutual friend, Katie Anderson talks about your own personal, personal Hoshin Kanri. So I, I took her a seminar actually, after I retired and I have no personal, I have no professional Hoshin Kanri anymore. So the idea here is could I apply this to my retirement? And the answer was a resounding yes. So the whole idea here is cascading some overarching goal eventually down to some daily actions. So, so I've categorized my goals in three, maybe four categories. I talk about mind, body, and soul.

Elliott Weiss (47m 8s):

So I want activities that keep my mind fresh. So I thank you mark for bringing me here today, because these are the kinds of conversations that, that does that. For me, it has to be good questions and talking about that body. So I'm working try to do some exercises, stay healthy. And so, you know, for the heart more than just me, part of a larger community, and then there's fun. I want to have fun too. That's kind of boring. I'm going to do a strategy or policy deployments on my life. And you know, what a key thing to do. You know, maybe I have fun doing that. So what I try to do is given those long-term goals of developing mind, body, and soul while having fun.

Elliott Weiss (47m 54s):

And I roll those back into monthly or daily activities, try to make sure every day have I exercise every day, have I done something to expand spammed my mind? What am I doing to make sure that I realize I'm part of a larger purpose in life? So there's the soul. So I've, I've been trying to do some personal training and reading more that should be taking some religious study classes online. It's actually been one of the benefits of COVID shame. We had to go through all this, but the fact that all these courses, now I can take from the privacy of my own little office here.

Elliott Weiss (48m 35s):

It's just wonderful. So that's been a great thing for me to do it. So again, it goes back to me and some of the questions you've asked, you know, if I really believe in this lean stuff, but I really believe in continuous improvement. I noticed she ought to be able to apply it in my own personal life. So that's, that's what I'm always looking to do, except for cleaning up my base.

Mark Graban (48m 56s):

I was just going to say it, but yeah, I was going to bring it back to that. I mean, there, there may very well be more benefit to you personally from that strategy deployment, Hoshin, Conrad approach than the basement, unless cleaning up the basement is one of those things that, I mean, does that help with body or you're moving stuff, carrying stuff, maybe throwing some things away or maybe mind and soul when it comes to relations with your wife and her being happy with you or not.

Elliott Weiss (49m 29s):

I'm not going to go there,

Mark Graban (49m 33s):

But I, I think you raised, you raise a really important point there of not just having goals. Right? Cause a lot of people start the year with this resolution that may be focused on a goal without then connecting it to the practical actions. So somebody may have a resolution that says I'm going to lose some weight. Okay. Well, that's, that's just a goal, maybe better for somebody to say I'm going to exercise daily and then connect it to, well, the reason why, because then when you, you don't feel like doing it on a certain day when you can connect back to the purpose, I think that helps in terms of motivation and, and following through.

Mark Graban (50m 17s):

So I think, you know, goals and actions, and like you said, having that tight connection can be really helpful.

Elliott Weiss (50m 24s):

Yeah. And then of course it's easier for me as an individual because I don't have to balance other for the most part, other people's goals and objectives and resource allocations is a lot easier for one person then multiple people, you know, and again, I'm not imposing this on anybody else having negotiate with different divisions of the organization.

Mark Graban (50m 48s):

So I was going to ask, are you getting input from your wife as a key stakeholder to your mind, body and soul success?

Elliott Weiss (50m 56s):

We're, we're a partnership. So yes, we work on this together. We share the personal trainer and she certainly encourages me to do the exercise and the more I do with a body and soul, the less I'm in her hair. So it becomes kind of some positive as well.

Mark Graban (51m 20s):

Well, this has been a lot of fun and I see the book behind you. And it was my defect in my process. I did mean to mention your book upfront during the introductions, a book of really, really interesting and very, very readable case studies and scenarios related to lean. Maybe one thing we could touch on briefly here. And again, I encourage people to go check out the book, The Lean Anthology. There, there was a chapter when I was looking at the table of contents that I really took interest in earlier, you mentioned statistical process control, not overreacting to noise. There's a chapter there about an individual using SPC charts, or you use the terminology.

Mark Graban (52m 4s):

I like process behavior charts that comes from Don Wheeler when, when it comes to monitoring blood sugar and managing diabetes, you know, could, could you, could you sort of share just a couple of perspectives on the application of, you know, a technical method like this or a management method and how that could be applied to someone's health measures and health outcomes?

Elliott Weiss (52m 28s):

Sure. Mark. So, so again here, the idea is with, within any, any process within every process, there's variability and there is a standard variability, regular variability, and then there's assignable causes. What I don't want to do is overreact to this normal variability, the variability that just happens so that when in this chapter was measuring his blood sugar blood sugars can go up and down throughout the day, depending on certain things. And as long as it's within these control limits, press the paper chart, we call them control limits as well.

Elliott Weiss (53m 13s):

Right. But they're based as opposed to physical process control. We're taking sample, we're looking at a run chart of these. So as long as we're in those limits, it's okay. And you're only to react when there's some special costs. Now, if our friend and I think his name in the chapter was Tracy Scott. If he is managing his blood sugar and his doctor has given him a certain range, that's good or bad. So it goes back to our, to Gucci spec limit the spec limits. It's okay for this variability to be out of control. If we're in the spec limits. Cause then I have a really nice tight, tight distribution.

Elliott Weiss (53m 56s):

But when I go out of control now, Hey, what happened? And his game that he played was how do I made it a, almost like a video game? How, what do I do? And my diet and my lifestyle was exercise to, to narrow this variability. So he was turned out to be successful. And then the other way he used the dataset was as he changed his diet, he actually noticed that the variability went down. So, Hey, there were enough data points that indicated that, Hey, this was a process change that created a statistically significant apple change.

Elliott Weiss (54m 37s):

And it was for the good. So then he's going to change his cooking and control limits is going to be even tighter. Now, what do we say? Quality is the only race you lose by finishing. So we're just gonna keep going and try to get a tighter and tighter, but he's also the other, my other sign behind me says, don't let perfect get in the way of better. Yeah. So it's okay for there to be some variability there, there has to be, I can't expect exactly the same blood sugar level, but as we spoke about earlier mark, now the question is how do I get the diabetic to believe this and want to do this? So it becomes a people change process, not a continuous glucose monitoring problem

Mark Graban (55m 22s):

Back to, again, as you put it, the knowing doing gap, whether it's me philosophy my teeth. That was the thing we talked about before we hit recording. I know I'm supposed to floss my teeth every day, but I sometimes fall short of that goal. And I go to the dentist and they reiterate the knowledge when it's more a question of motivation and change. You know, when you talk about, you know, fitness goals or health or weight, I mean, one lesson I've tried to take from a process behavior charts and SPC is that your weight, even if, even if you're at a point where you want your weight to be stable, it's not going to be the exact same number every day, especially if your scale measures tenths of a pound.

Mark Graban (56m 9s):

So there are some you'll read. People will read advice sometimes from wellness experts who will say to avoid over reacting, only weigh yourself once a week. I'm like, well, okay, that would be one strategy. Or you could weigh every morning and just learn how to not overreact. I'm four tenths of a pound heavier than I was yesterday. Not a big deal. I may be 0.7 pounds lighter tomorrow. This happens. And everybody's, body's a system is going to have its own variation based in depends on lifestyle and other things too.

Elliott Weiss (56m 45s):

So, so mark, for the next time we get together, I have a case study on using a three analysis for weight loss. So, and it talks about, about some of these things. Again, there's, there's obviously a difference between knowing and doing

Mark Graban (57m 6s):

It as, as people tend to say in this space and it becomes cliche. It's a journey, right? So good luck to you Elliot on your journey this year and, and beyond. And, and, and, and you know, you've done, there's, let's brainstorm at some point. I mean, I'm sure we could do an entire episode at some point, talking about some of your work and experience in healthcare. Elliot is also the author of a chapter from a book called Lean Tools for Service Business Model Innovation and Healthcare. Between that and other healthcare experiences. I know we could find a lot more to talk about maybe a little bit on sports too.

Elliott Weiss (57m 44s):

That'd be great.

Mark Graban (57m 47s):

So again, our guest today has been Elliott Weiss. You can find his bio page and CB and all of that detail. If you go to ElliottWeiss.com that forwards to the page on the Darden website. And again, I do recommend go check out the book, The Lean Anthology. It was co-authored by you and I don't have your coauthor's name handy,

Elliott Weiss (58m 12s):

Rebecca Goldberg.

Mark Graban (58m 13s):

Okay. So I make sure we give credit to her. So Elliott Weiss, Rebecca Goldberg. Elliot, this has been a lot of fun. Thank you for, thank you for being a guest today.

Elliott Weiss (58m 22s):

Well thank you for having me. It was fun for me as well.

Announcer (58m 25s):

Thanks for listening. This has been the lean blog podcast. For lean news and commentary updated daily, visit www.leanblog.org. If you have any questions or comments about this podcast, email mark leanpodcast@gmail.com.

Please scroll down (or click) to post a comment. Connect with me on LinkedIn.

If you’re working to build a culture where people feel safe to speak up, solve problems, and improve every day, I’d be glad to help. Let’s talk about how to strengthen Psychological Safety and Continuous Improvement in your organization.

[…] You can watch the video, listen to the audio podcast or read the show notes at https://www.leanblog.org/2022/02/prof-elliott-weiss-on-steph-curry-tweaking-his-3-point-shot-and-not… […]