By Joseph E. Swartz (in honor of my father, James B. Swartz)

“He could have added fortune to fame, but caring for neither, he found happiness and honor in being helpful to the world.”[i]

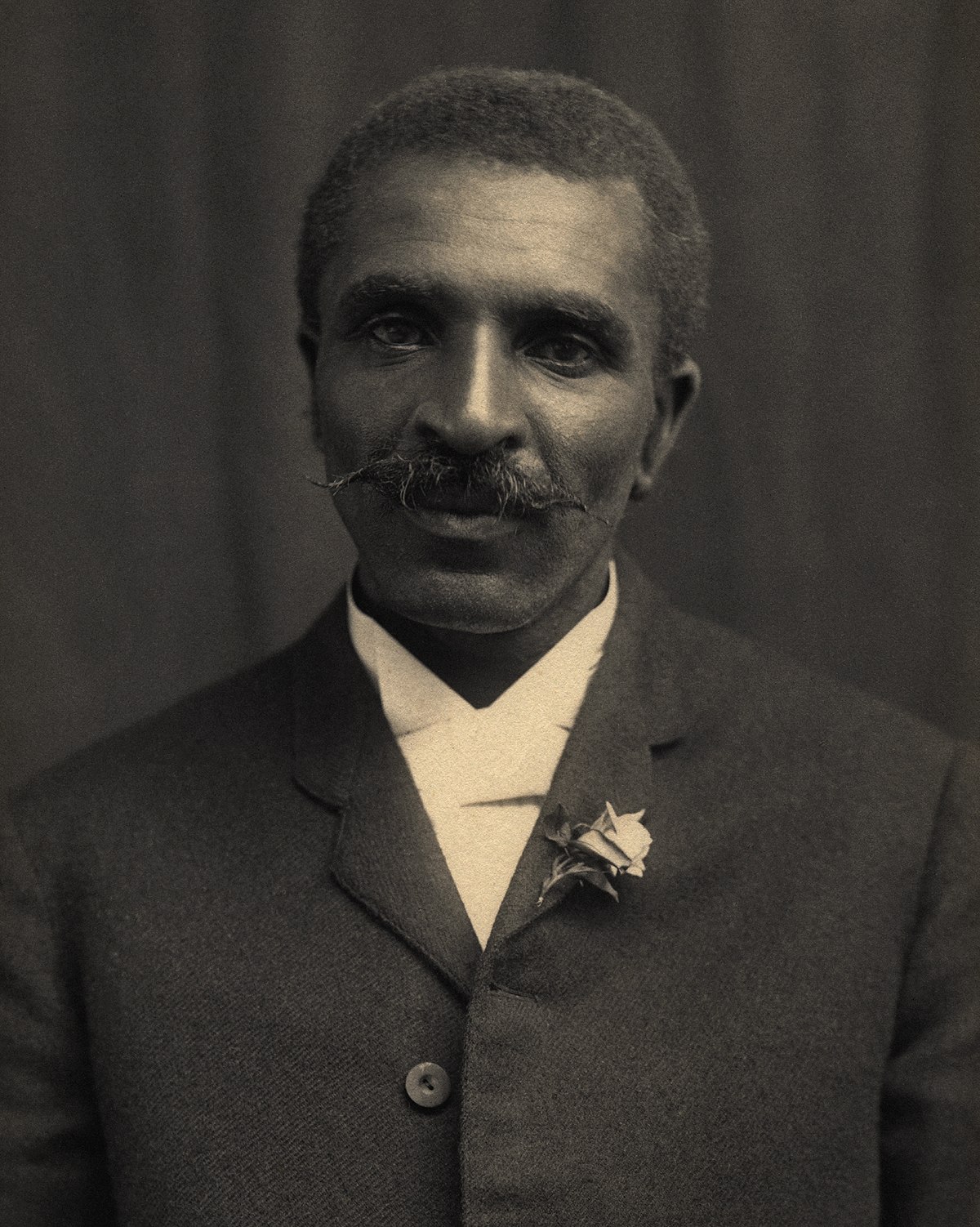

George Washington Carver's epitaph.

When I was 12 years old, my father moved my mother, my siblings, and me from a small town in the Midwest to Tuskegee, Alabama. We found ourselves in a strange world. We were culturally the minority. Everyone in town was African-American, except us, one other white family, and one Hispanic family. Our father taught us that we needed to learn and respect the local culture.

A sweet 77-year old lady lived in the woods not far behind our house. We knew her as Mrs. Kelly. Her full name was Hattie West Simmons Kelly.[ii] We learned that she had been a graduate student and teaching assistant to George Washington Carver (1864-1943) and was later Dean of Women at Tuskegee Institute (now Tuskegee University)[iii]. She told us stories about “Mr. Carver” that were enthralling. As an impressionable 12-year old, I took in every word.

Through those stories, George (as I will call him) became my childhood hero. Mo Rocca, of the show Henry Ford's Innovation Nation, called George one of our great American heroes. George was the first African American to receive a master's degree in agriculture and was known as one of the greatest American agricultural scientists. Some know him as the “peanut scientist.” He was so much more. He was great to me first because he was a great and honorable man.

Respected All People

Through the stories told by Mrs. Kelly, I earned respect for George, and through him, respect for all people because he deeply respected and honored all people. He refused to participate in discussions around racial issues because he saw them as divisive. He was more concerned about the common good of all people – from the poorest to the richest. He frequently visited with poor farmers and sharecroppers to understand their challenges. He was called before the US House of Representatives in 1921 to give a ten-minute speech on the subject of tariffs. He so enlightened and entertained the House that they kept extending the time for another hour and thirty five minutes.

A Humble Leader

Mrs. Kelley said if you saw George out walking you might mistake him for a homeless man, as he often didn't pay close attention to his clothes. He could have gotten rich by selling his product ideas, yet he refused to accept any money for his ideas and inventions because he believed they came from God. He would ask God questions about the plants he was studying and God would answer him. He wasn't interested in money; he was only interested in showing possibilities.

Purpose-Driven – To Be of the Greatest Good

George was on a quest to be of the greatest good to all of mankind, and especially that ‘furthest down' man by helping them with their basic needs such as food.[iv] He wanted to preserve the small family farm, and saw science and technology as the way.

A Problem Solver

In the 1920's, the boll weevil, a beetle, wiped out 75% of the cotton crop in the United States. In the early 1900's, cotton was king, and it was the main crop for the southern tenant farmer or sharecroppers. But cotton was being decimated by the beetle. Small farms were affected the most as they didn't have the resources to battle the beetle. However, what these farmers didn't know was that cotton used up the nitrogen in the soil. Reliance on one crop caused overproduction of a commodity item that declined in price over time but not in cost to produce. The problem was exacerbated since constant cotton planting depleted nutrients from the soil, which left the later crops weak and susceptible to disease and bugs. Some year's entire crops were destroyed by boll weevils. The farmer was forced to cut down more forest to produce more crops, increasingly using parts of the hillier land which resulting in quicker soil erosion, resulting in more work on less productive land, and less and less profit. For many, cotton was costing more to grow than it was selling for.

George recognized that the root cause of the problem was that cotton depleted the soil of nitrogen and other nutrients. George recognized that the sharecroppers couldn't afford fertilizers and pesticides. He determined that they needed a crop that they could produce in nutrient poor and rocky soil, to both feed their families and also sell at a profit, and also restore the lost nutrients. George hypothesized that other plants could return the missing nutrients to the soils. George found that peanuts, beans, pecan nuts, cowpeas, and sweet potatoes pulled nitrogen from the air and returned it to the soil, and therefore improved soil that was depleted by cotton. Additionally, they were not susceptible to the boll weevil.

Recognizing the problem, the government began subsidizing agricultural research at universities. The USDA started supporting dozens of other agricultural research programs throughout the country, including George's program at Tuskegee Institute. However, the research attracted big business sponsored seed, fertilizers, and farm equipment that only large plantation owners could afford. Only George's program sought to target the common man, targeting organic farming on depleted soil, using common seeds, a horse and a plow. George had learned that without fertilizers, adding nutrients back to the soil required adding organic wastes and crop rotation. However, to convince the small farmer to switch to other crops required convincing them that it would be worth their while.

There was not a big market for peanuts and sweet potatoes. So, he had to figure out how to create one. So, George devoted himself to discovering wide uses for the peanut. In his lab, he broke apart the components of peanuts and sweet potatoes. Then by recombining the components he created useful by-products.

He found over three hundred useful by-products of the peanut, including peanut butter, peanut milk, peanut oil, flour, candy, ice cream, shampoo, glue, wood stain, ink, breakfast foods, margarine, washing powder, bleach, shoe polish, metal polish, axle grease, cattle feeds, plastic, shampoo, soap, shaving cream, etc.

He found over one hundred useful by-products of the sweet potato (flour, syrup, starch, molasses, glue, vinegar, alcohol, synthetic rubber, shoe blacking, a coffee-like drink, etc.) For the pecan nut he made more than sixty useful by-products.

All total, he developed several hundred industrial uses for peanuts, sweet potatoes, and soybeans and developed a new type of cotton known as Carver's hybrid.[v] He helped develop new markets for peanuts, sweet potato, and soybeans.

He experimented and proved his hypothesis and then taught his new techniques to farmers who would listen. To get the word out, he published research bulletins. He wanted to create a pull for the by-products of the plants, so he targeted three groups of people: farmers, housewives, and teachers. They contained simple cultivation instructions for the farmers, history and plant science for the teachers, and recipes for the housewives. Unlike other research bulletins, his were written at a level low enough to be readable to these target markets. He avoided scientific language, or carefully explained it whenever he felt he had to introduce it. He created hand drawn illustrations to help explain to those who could not read well.

He is now considered the father of the $65 million peanut industry of the Southern states.

By not listed; restored by <a href=”//commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/User:Adam_Cuerden” title=”User:Adam Cuerden”>Adam Cuerden</a> – Tuskegee University Archives/Museum, Public Domain, Link

Knew the Value of Hard Work

Mrs. Kelly said George regularly worked through the night in his lab – so focused on his quest that he would forget to eat his dinner. He would frequently work, eat, and sleep in his laboratory for days in a row. Mrs. Kelly would take Dr. Carver meals and would sometimes find him sleeping at his desk.

Taught Scientific Experimentation

He taught his students to experiment. Each student was allocated a small plot of land in which to grow a garden. George expected them to get their hands dirty, and plant many of the plants he taught them about. He, then, wanted them to do the experiments on those plants that he taught them about. He also taught other professors at Tuskegee to experiment for companies. One example was experimenting with types of ink for Parker Pen Company. He felt that experimentation was the best way to learn, as only then students would see for themselves.

Disgust of Waste

Moses was George's adoptive father until he was 12. Moses influenced George to have a disgust of ‘wastefulness.' This would later drive him to figure out how to make everything a farmer has useful, such as using southern clay for dies and paint. Mrs. Kelly said George would save everything. You would often see him stop at a trash can and dig things out that he would later use in his art or his crocheting or needlework. He taught that plants were created by God for our use, and that every plant had a purpose. Mrs. Kelly said she grew up feeling that nothing should be thrown away, because George demonstrated how to reuse everything. He found hundreds of ways to use the peanut and how to use every single part of various plants. What made George unique is that he figured out ways to use a number of things that people never thought to use. He showed how peanut hulls, which had been wasted for centuries, could be utilized.[vi] He believed that nature produces no waste. “Waste, he declared is man-made, because of the failure to understand the unity of the universe.”[vii] “Both waste and shortages occur when man ignores the whole and attempts to conquer, rather than utilize natural forces.”[viii]

Taught His Students to Think for Themselves

Mrs. Kelly said that when students asked George a question, he would turn it around and ask them what they thought the answer was. If the answer wasn't quite right, he would say, “go look it up.” He had a saying,

“Figure it out for yourself, my lad. You've all that the greatest of men have had, two arms, two hands, two legs, two eyes and a brain to use if you would be wise. With this equipment they all began, so start for the top and say, ‘I can.' …“[ix]

Knew the Value of Continuous Life-Long Learning

Mrs. Kelly said George was interested in learning about anything and everything. He was a recognized artist. Four of his paintings won honorable mention at the World Exposition in Chicago. He wrote poetry, sang, did needlework, and played various musical instruments for local dances. He was an author of numerous books and articles.

System Thinker

He believed that everything is interconnected in a system, and “any action must be considered in the light of its overall long-term consequences, not just its immediate benefits.”[x] Analysts of his work have said that he made no significant breakthroughs in science. Few of his ideas were original, and he borrowed heavily from other research. Most of his work was considered simple. What he did do is he integrated and applied all the knowledge he had learned during a lifetime, combining several branches of science. Because of his approach, he influenced the people, the markets, and the world like no other agricultural researcher. He once commented,

“When you can do the common things of life in an uncommon way you'll command the attention of the world.”[xi]

Suffered Greatly

The Efficiency Magazine of London England said, of all living men, he had the worst start and the best finish.[xii] He was born into slavery, and knew neither his blood mother, nor his father. George was a sickly child, suffering from frequent severe bouts of whooping cough and tubercular or pneumococcal infections. He later wrote that his body was in ‘constant warfare between life and death.‘[xiii] The illness was so severe that he could barely talk when he was young, and until his death suffered from frequent chest congestion and loss of voice. He lived in poverty most of his life. Later in life, he continually referred to himself as, “a poor defenseless orphan.”[xiv]

Constantly Searched for Better Ways

Because of George's poor health, he was exempted from the more difficult chores around the farm and was pampered by his adoptive parents, Moses and Susan. He had “considerable freedom merely to be a boy.”[xv] Much of his time was spent hiking through the woods searching for plants, rocks, bugs, frogs, and reptiles. He acquired a love of nature, and a need for the solitude of the forest. Every morning, before the sun would rise, he would walk through the woods searching for new discoveries. “Later in life, his predawn ramblings in the woods would become legendary.”[xvi] He learned how to nurse sickly plants back to health, and became known in his neighborhood as the ‘plant doctor.'[xvii]

An Honored Man

Some of the greatest manufacturers in the country consulted him.[xviii] Thomas Edison offered him a six-figure annual salary to come work with him, which would amount to well over a million dollars in today's money. He turned it down. Henry Ford wanted his help and they frequently corresponded and visited each other. In 1942 Henry Ford erected a building in his Greenfield Village in this man's honor. Time magazine called him the ‘Black Leonardo,' a reference to Leonardo da Vinci, a genius in many fields.[xix] Joseph Stalin, the Russian dictator, asked him to come oversee the farms of Russia.

He was one of the first scientists to experiment with synthetics, such as synthetic rubber, which became instrumental to the Allies victory in World War II.[xx] Several US presidents visited him. US President Franklin D. Roosevelt later commented at his death, “

The world of science has lost one of its most eminent figures…the versatility of his genius and his achievement in diverse branches of the arts and sciences were truly amazing. All mankind is the beneficiary of his discoveries in the field of agricultural chemistry.”[xxi]

Nearly every large city in the US has something named after him. He was considered the world's greatest botanist.

A Lean Thinker

George influenced me to set my sight on becoming a scientist that integrates business to help people improve their lives – and I think that is what I have attempted to become. At the time I didn't realize it, but George modeled Lean Thinking to me. He taught me humble leadership, respect for all, problem solving, experimentation, disgust for waste, life-long learning, system thinking, and more. I believe we all need a hero like George.

[i] www.biography.com

[ii] Hattie West Simmons Kelly (1896-1982).

[iii] From conversations with Mrs. Kelly.

[iv] In a letter from George Washington Carver to H.G. Ritchie, Oct. 7, 1938, (Box 39, GWC Papers).

[v]Historycentral.com

[vi] J.A. Rogers, World's Great Men of Color, Volume 2, (Simon & Schuster, New York, 1996), p. 471.

[vii] Linda O. McMurry, George Washington Carver: Scientist & Symbol, (Oxford University Press, New York, 1981), p.309.

[viii] Linda O. McMurry, George Washington Carver: Scientist & Symbol, (Oxford University Press, New York, 1981), p.309.

[ix] George's quote is from a poem called, “Equipment” by Edgar A. Guest. www.tuskegee.edu/support-tu/george-washington-carver/carver-favorite-poem

[x] Linda O. McMurry, George Washington Carver: Scientist & Symbol, (Oxford University Press, New York, 1981), p.309.

[xi] J.A. Rogers, World's Great Men of Color, Volume 2, (Simon & Schuster, New York, 1996), p. 467.

[xii] J.A. Rogers, World's Great Men of Color, Volume 2, (Simon & Schuster, New York, 1996), p. 469.

[xiii] David A. Adler, A Picture Book of George Washington Carver, (Holiday House, New York)

[xiv] Booker T. Washington, My Larger Education (New York, 1911), pp. 225-26.

[xv] Linda O. McMurry, George Washington Carver: Scientist & Symbol, (Oxford University Press, New York, 1981), p. 15.

[xvi] Linda O. McMurry, George Washington Carver: Scientist & Symbol, (Oxford University Press, New York, 1981), p.19.

[xvii] J.A. Rogers, World's Great Men of Color, Volume 2, (Simon & Schuster, New York, 1996), p. 463.

[xviii] Linda O. McMurry, George Washington Carver: Scientist & Symbol, (Oxford University Press, New York, 1981), p. 466.

[xix] David A. Adler, A Picture Book of George Washington Carver, (Holiday House, New York)

[xx] J.A. Rogers, World's Great Men of Color, Volume 2, (Simon & Schuster, New York, 1996), p. 471.

[xxi] J.A. Rogers, World's Great Men of Color, Volume 2, (Simon & Schuster, New York, 1996), p.470.

What do you think? Please scroll down (or click) to post a comment. Or please share the post with your thoughts on LinkedIn – and follow me or connect with me there.

Did you like this post? Make sure you don't miss a post or podcast — Subscribe to get notified about posts via email daily or weekly.

Check out my latest book, The Mistakes That Make Us: Cultivating a Culture of Learning and Innovation:

Very interesting & useful for me !

Thanks