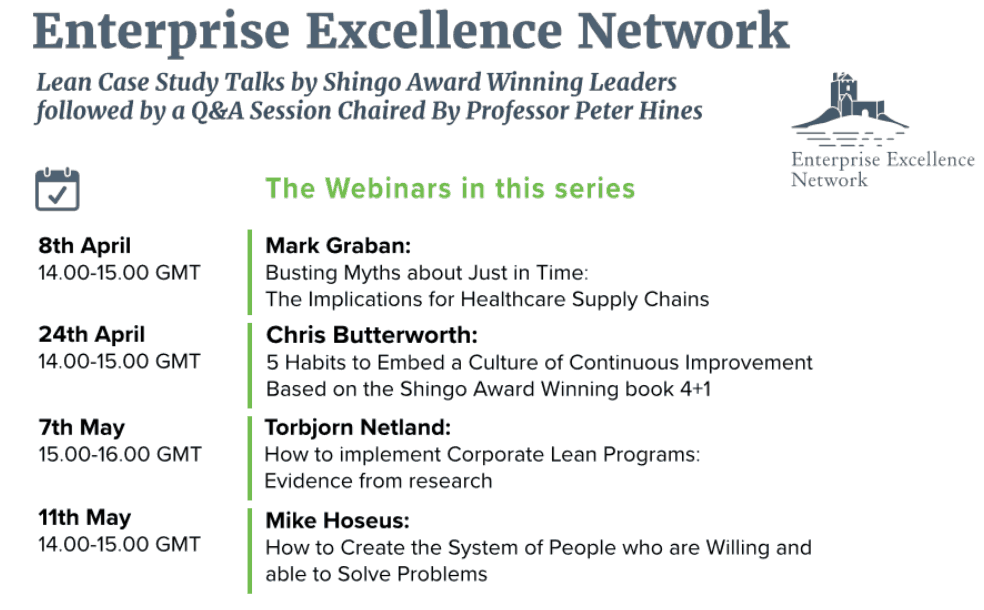

Thanks to Professor Peter Hines and the Enterprise Excellence Network for inviting me to present this webinar. Mine was the first in a series of free webinars that they are hosting in the coming weeks, presented by Chris Butterworth, Torbjorn Netland, and Mike Hoseus.

You can learn more about the webinars via the LinkedIn Group, “Lean Business System” and this post.

They've allowed me to share the recording of the webinar — it's 30 minutes of presentation with Q&A and discussion that follows.

Webinar description:

During the Covid-19 crisis, some have blamed “just in time” or “Lean” for the current (and tragic) shortages of life-saving items like masks and ventilators. JIT has been vilified after nearly every major natural disaster that has disrupted supply chains. Is this fair? In this webinar, Mark Graban, a Shingo award-winning author, will dispel some common myths about just in time and Lean management. He will share a broader context of JIT and Lean, along with practical suggestions that can help organizations in various industries.

Learning Objectives:

- Why JIT is not simply “low inventories”

- How JIT fits into the broader context of the Toyota Production System and Lean

- Why “lowering the water to expose rocks” can be dangerous if not done well

- How Kanban and “supermarket” systems work during the best of times

- How strategic inventories might protect us during bad times (but not the worst of times?)

You can also view the slides, additional resources, and links to content I cited on this page.

Transcript

Emma: Good afternoon or good morning depending on where you are, to the Enterprise Excellence webinar series with Mark Graban on Busting Myths about Just in Time — The Implications for Healthcare Supply Chains. Welcome to everyone.

I'm just going to start off with a few housekeeping rules. As you'll see on your tab, there's a Questions tab. There is a dedicated Q&A session after Mark's presentation, which will last for about 30 minutes. You are welcome throughout the webinar to ask questions using that Questions tab. We will then go through them during the 30-minute Q&A time at the end.

That's pretty much it in terms of the functionality. Now, I'm going to go on and talk about the Enterprise Access Network what we do here. The Enterprise Excellence Network is a professional community that was founded by Professor Peter Hines, and is exclusively for senior Lean leaders in Europe.

The network provides benchmarking events, and so we have provided in the past quarterly networking events at bespoke and benchmark host sites, including Abbott Diagnostics and Halsey, companies that are really representing Enterprise Excellence. These Enterprise Excellence webinar series are, during these difficult times, as a way of keeping people connected.

This is the first one of the series, which is delivered by Mark Graban. I'm going to hand over to Professor Peter Hines just to give you a bit of background on himself.

Professor Peter Hines: Hello, and welcome to the webinar. For me, I think Emma worked to find the worst photo of me. Anyway, there it is. I'm going to be hosting this webinar, and Mark will be giving the talk. I'll compare your questions. As Emma said, if you want to put those in the question box, then I'll pick those up at the end of the session.

With that, I'm going to hand on to Mark. Mark, I think we've known each other for about 11 years. We happened to sit next to each other at a conference dinner in Nashville in 2009 at the Shingo Conference when we were both the receiving publication award there. I think we both found out a little bit about ourselves.

As we were just chatting beforehand, I don't think we said let's do a webinar together 11 years' time, but we see [laughs] something doing that. Those of you familiar with Mark, Mark's work is very well known, particularly in the healthcare sector.

This webinar came out of a posting he made on LinkedIn talking about “Just-in-Time” and in healthcare, which is obviously very personal to the moment. With that, I'll hand over to Mark, and then we'll take some questions in about half an hour.

Mark Graban: Thank you, Peter and Emma. I appreciate the invitation. Thank you to everybody who has tuned in to watch. Today, I want to share some thoughts maybe around Busting Some Myths about Just in Time and The Implications, maybe not just only for healthcare supply chains but also for people in other industries.

I started my career in manufacturing. I spent 10 years really focused on manufacturing. I thought that was going to be my career. Now, I've ended up working primarily in healthcare for 15 years. The slides and different links that I'll reference in my talk links to books, videos, and articles can all be found on my website. There's a page markgraban.com/jitmyths. I'll put that up again at the end.

This is the first webinar that I've done in this era. You might call it the era of no haircuts, or in my case last Saturday, it was the first home haircut that I ever received. Thanks to my wife. We might get to see that later during the Q&A session. I think that's called the teaser to maybe get you to stay tuned.

But hopefully, the thoughts that I'm sharing are much more important issues than haircuts, will keep your attention over these next 30 minutes because this era of the coronavirus and COVID-19 is an era of increased, if not, unbearable stress on the healthcare systems in different countries. I'm sure we're all quite aware of headlines from different countries.

Here in the US, severe shortages. In Canada, there are worries of shortages ahead of the expected COVID-19 search. In England, sad to see a headline. Similarly, things are happening here in the US of NHS workers having to wear plastic bags as protection because they don't have enough gowns.

How do we meet these needs? How do we plan better for the next time? How do we react now? There was a great episode of “The Planet Money Podcast” that I listened to last weekend about this race, this reaction to make ventilators. There are a lot of interesting admirable efforts going on right now.

As the host said at the end of the episode, “We're perhaps facing the greatest supply and demand mismatch in our lifetime.” As Lean thinkers and practitioners, we're thinking about the goal is matching supply and demand. That might be difficult in normal times, but what about unusual times like today?

I've heard some referred to the pandemic as a proverbial black swan. If you know the phrase made popular by Nassim Taleb, a black swan is a rare, unforeseeable, unpredictable, unimaginable event. Taleb said in the video that I watched that 911, for example, was a black swan, even though some warned about that threat.

He said in that video that what's going on right now is not a black swan. It is a white swan. It was predictable. It was a matter of not if but when? A lot of the effects we're seeing are in his view, preventable.

He said fairly bluntly, “There's no excuse for companies or governments to not be prepared for this” The people that say, “We couldn't have seen this coming,” you didn't have to be as smart and as accomplished as Bill Gates to see this coming.

There's a “TED” talk that he gave in 2015 that has been making the rounds more recently where he warned that a virus like the 1918 Influenza Pandemic, which spread very quickly in our modern world, so it was unprecedented. It's maybe unprecedented in our lifetime. The last pandemic was just over a century ago.

As Bill Gates said, “We've actually invested very little in the system to stop an epidemic. We're not ready for the next epidemic.” We haven't stopped it. We haven't prevented it. The question then is, are we ready? Did we expect to be ready in different ways?

In my research and gathering of materials for the session here, I find a “Wall Street Journal” article. The headline is alarming. “Just-in-time inventories make US vulnerable in a pandemic. Low stockpiles hospitals boost efficiency,” I don't think I would use the phrase boost efficiency. It might be more like cuts cost. “But leave no extras for flu outbreak, yet alone, a pandemic of this nature.”

This is an article from 14 years ago. We should have seen this coming. As it said in the article, “The University of Utah like many big hospitals carries a 30 days' supply of drugs.” Part of it is because it would be too costly or wasteful to stockpile more. That's a judgment decision.

What about the waste of not having enough? Drugs, supplies, equipment, staff, or rooms? Classic inventory planning theory and practice has often traded off the cost of inventory with the cost of stock outs, and in something as important as health care. People continually point out that patients are not cars that a yes, that's absolutely true.

Patients are more important. We should perhaps err on the side of protecting ourselves and our patients. As I wrote in my book, Lean Hospitals, “When the cost of stockouts is high,” — and this could mean the human cost — “we have to err on the side of excess inventory.” The question is how much? How do we accomplish that? How do we plan and react to a pandemic?

I've never had a hospital client say to me that, “Our goal is to eliminate all of our pharmaceutical inventory.” More likely the problem statement that they're working on is preventing stock outs, even in normal times. This is a problem in organizations before Lean. I'm not sure the association between just-in-time inventories and our current situation is correlation, yet alone causation.

In this article, they said, “At that time, 77 other drugs are in short supply because of manufacturing, and other glitches, such as shut down factories.” As I said at the time, “The supply chain is horribly thin.” That was true in normal times. Even if we wanted to magically pile up stockpiles of inventory, is that possible with our supply chain?

Is it fair to ask anybody in any industry to suddenly absorb a 20x spike in demand? There was a blogpost written by a doctor that went through some of the math here, that if a hospital goes from 10 infectious patients a day that require special PPE and protections for staff, and you suddenly go to 200 of them, the need for masks goes from 10,000 a month to 200,000 per month.

If you're an academic medical center, you would probably need two to three times this number. That might actually be a 60x spike in demand. Can any system, just-in-time or just-in-case or whatever, absorb a 60x spike in demand? This is a very difficult thing to ask.

The radio program in the US Marketplace had very interesting piece a few weeks back. The title here, again, points to just-in-time. It says, “The just-in-time manufacturing model is challenged by COVID-19.” They said at issue here is a model — and I take issue with this — that focuses on low cost and low inventory.

I may be preaching to the choir here, but I said, “Wait a minute. Lean focuses on flow and other factors. It's not anybody can do low cost and unreasonably low inventory without bringing Lean or just-in-time into the equation.” Cost cutters can do this.

There's a model where all parts arrive at the plant just in time. I'm like, “Well, what does that mean even in manufacturing. It's not like parts arrive on a truck one at a time.” There's some element of thatching. There's some element of inventory, even in a Toyota plant, and in any other very Lean organization.

One myth that still spreads in the media and in different industries is a myth that says just-in-time means low inventory, or even worse, a myth that says just-in-time means zero inventories.

What does Toyota say about just-in-time? We can go to their corporate website based in Japan. It's in English. They talk about the Toyota production system as being, for one, about just-in-time. You can see they describe it as making what is need, when it's needed, and in the amount needed.

There is nothing here about saying, “We should cut corners on inventory,” or, “That the goal is low inventory.” The goal is what is needed, when it's needed, in the amount needed. That's critically important in healthcare.

If you look at Taiichi Ohno's classic book, he says, “Just-in-time means that there's a flow process.” If we have batchy, long, slow supply chains, is that really a flow process? Ohno says, “A company establishing this flow throughout can approach zero inventory.”

There are too many cases of organizations that have put the proverbial cart for the horse. They've gone for low inventory without establishing flow.

I was fortunate that early in my career, literally a Japanese sensei that I was fortunate to learn from. We were at a client, a manufacturing organization that had somehow decided that they should eliminate all of their inventories, and now they were struggling to meet customer demand.

The sensei said, and I thought this was quite reasonable,

“Job one is meeting customer demand. Job two is low inventory.”

We have to make sure we don't get those priorities out of sync. It's meeting customer demand without excess inventory. The amount of inventory required to meet that demand depends on not just our production system design but our supply chain design and execution.

Going back to Ohno, he described just-in-time as an ideal state. He said,

“Obviously, it's extremely difficult to apply this in every process in an orderly way. Every link in the just-in-time chain must be connected and synchronized.”

Again, I would argue in healthcare, we have not had that.

The idea that low inventory or just-in-time would be easy or achievable is something Ohno might have used this phrase that he used in the book that just-in-time seemed to contain an element of fantasy. Something made us think it would be difficult, but not impossible to accomplish.

I think where organizations have gotten in trouble is when they have though just-in-time is easy. “We'll just get rid of the inventory,” but that doesn't work.

You might be familiar of the old analogy or parable about lowering the water to expose the rocks. You look at a group here. The person in the boat is smiling because I'm sure they're looking downstream. While it might be a challenge, they probably expect to survive.

In the introduction to the book by Ohno, Norman Bodek wrote,

“Lowering the water level in the river to expose all the rocks enables them (people) to chip away at all the problems.”

Again, this takes time. This takes effort. We may lower the water and we may expose some rocks, but we need a river that we can actually navigate and survive.

In a more modern book, The Toyota Way Fieldbook, the author says,

“As long as the rocks, like problems, are covered with water, like inventory, it's smooth sailing. But if the water level is lower, the ship can be quickly demolished by running into the rocks.”

We don't want to see a stream ahead that looks like this, where our boat is only going to crash.

As we're trying to lower the water more gradually, expose rocks that require problem-solving capabilities, not just low inventory. As we ease into that, we can find advice from Shigeo Shingo in his classic book. This was shared on LinkedIn recently by my friend, Sami Bahri, who's been called the World's First Lean Dentist.

Shingo talks about using something called a cushion stock system. Shingo is not making this unreasonable, easy leap to immediate just-in-time that we run trials that are going to be problems. He didn't think it unreasonable to borrow from that cushion stock to protect against unforeseen problems, so this balance of, again, lowering the water without crashing the boat, or the company, or the hospital.

There is a further myth that equates that TPS is only just-in-time. Some people and some publications, like the Wall Street Journal, use just-in-time as a synonym for Lean or the Toyota Production System. If we go back to the Toyota website again, they talk about the equal pillars of not just just-in-time, but jidoka.

The Toyota website explains this, and I quite often point people to the Toyota website. Jidoka can be translated as automation with a human touch. What this means is it's about built-in quality. When a problem occurs, the equipment stops immediately, preventing defective products from being produced.

The Toyota was innovative back in the day before they built cars when their products was weaving looms. Here's a picture from the Toyota Technology Museum in Nagoya. There's automatic stop-motion loom. You can see in this picture here what's called a broken warp. That is basically defective cloth.

The innovation with Jidoka was that instead of one person, one machine having to constantly inspect for breakages, the machine stops automatically. That's not as good as preventing the breakage, but at least stopping immediately is a pretty good strategy.

Lean is not just just-in-time. TPS is not just just-in-time. The Toyota Way talks about continuous improvement and respect for people. I think in health care, respect for people means respecting the patients and respecting staff by doing all that we can to not put them in an unsafe situation.

Toyota describes what they call an Integrated System. The Toyota Production System — they would argue, I would agree — is a system. There's a myth out there unfortunately that gets people in trouble, that says you can adopt one piece of a system and expect to get the same results from the system.

Ohno in his book says,

“A company cannot simply ask a supplier to adopt the system because adopting just-in-time means completely overhauling the existing production system.”

This might also mean completely overhauling the existing supply chain.

Where do hospitals get masks and gowns, and ventilators? What's the supply chain for producing, if you will, respiratory therapists and pulmonologist, and ICU nurses?

There was a very recent TED Talk. This was not predicting anything, but a doctor who gave a talk titled, “Why COVID-19 is hitting us now? How to prepare for the next outbreak?” In the video, she said, — think this statement a fact — “COVID-19 has also revealed some real weaknesses in our global health supply chains.”

She says then,

“Just-in-time ordering Lean systems are great when things are going well, but in a time of crisis, what it means is that we don't have any reserves.”

I think we should step back and ask, is that really true? Should we have reserves? I think, yes. What's reasonable versus what's a once in 100 year pandemic, though? That's a more difficult question to talk to.

The doctor said, “If a hospital or a country runs out of face mask or personal protective equipment, there's no big warehouse full of boxes that we can go to get more,” but there was supposed to be, [laughs] at least here in the United States. We have literally had something called a “Strategic National Stockpile.”

There was supposed to be a big warehouse or it's actually 12 warehouses in secret locations throughout the United States. There was supposed to be this strategic stockpile, but was it enough? That's the question.

The doctor again says, “You have to order more from the supplier. You have to wait. You have to wait. It's coming from China.” That's a supply chain issue, because Lean and just-in-time, this would be another myth, I guess.

It's a myth that just-in-time means, “Ship all your production to China, because that's a low labor cost country.” That's not Lean thinking at all. Toyota works to eliminate the time lap. When they built a plant in San Antonio, San Antonio, Texas is not in the midst of automotive industry's supply chains.

Toyota brought a lot of suppliers to the area and many of them are in literally a wing of the building that is rented out to suppliers. To help create the conditions where just-in-time was possible, Toyota made very different decisions than many other manufacturers of medical supplies have made.

If we go back to Marketplace, their headline maybe more accurately could have said, instead of pointing to just-in-time, “China offshoring manufacturing model, challenged by COVID-19.” Or the headline might have said, “Poorly managed strategic stockpile strategy, challenged by COVID-19”.

There was a news article about hospitals in Minnesota. There's a long history of a contentious relationship with the union, so that's part of the context here. Struggling, and the Nurses Association model was blaming this “Lean Model of Functioning.” It's strictly a cost-cutting measure. No.

There's nothing on the Toyota production system page, the Toyota corporate website that talks about cost-cutting. I'm not sure if the word “cost” even appears, because low-cost and low inventory is an end result of meeting customer demand with great flow.

Somebody from a hospital group said, “Even after going ‘Lean,' hospitals do keep excess inventory on hand. For mass casualty events like a tornado or a terrorist attack, but not for once in 100-year pandemic.” Again, I think one of these myths here is that Lean is all about cost-cut. That's not true.

Hospitals have a long tradition of harmful and dysfunctional cost-cutting before they ever learned about the word “Lean” or the phrase “just-in-time.” What could we do in situations like this, even with a once in 100 years pandemic? Three possible strategies perhaps.

One is lots and lots of inventory. A second strategy would be speed in our supply chain. A responsive supply chain that helps address changes in demand. Again, a 60x spike is really difficult to deal with. We can think about inventory, we can think about speed, we can also think about the idea of shaping demand, and this is where the idea of flattening the curve comes in.

It's why we're washing our hands, not touching our face. We're staying home not just when sick, we're staying home in general. Maybe now we're covering our mouths even if we are asymptomatic. We can try to spread out or lower demand for healthcare services.

Let's look at the first strategy. Was there enough inventories stockpiled? One article I read said, “Data showed hospitals believed that they were well-equipped, only to see their stocks depleted in a matter of days.” Inventory planning requires forecasting. The forecasts were probably not good enough here in this case.

Would this have been possible that hospital that now needs 200,000 masks a month at $2.50 per mask that would have been over $1.5 million to stockpile three months at that usage rate? Masks are not very large, so storing 630,000 of them requires really only a 600-square-foot warehouse, and a warehouse is cheap.

If we look at the balance here, the cost of inventory is much higher than the cost of warehousing space. Again, people tried the stockpile strategy, but we're nearly running out. Nearly 12 million or more have been taken from the stockpile, and now, it's almost empty. The Federal Emergency Management Agency recently ordered 180 million masks.

That would have been a $450-million stockpile, which might have been possible. It would have been possible probably. It would have been expensive, but compared to the cost of not having the masks we might have chosen to do so. I did the math of a different number 28 million masks.

Let's multiply this by six. It might require 1 million square feet of warehouse space, and a typical Amazon fulfillment center is about that size. Again, I think this would have been achievable. Again, it's a lot of money. It's a lot of space, but it's doable.

Now, we'd have to make sure we rotate that stock and avoid problems because there's maybe a different myth. Maybe not amongst Lean thinkers that inventory is risk free. We've seen recently, even if you were to pull supplies from safety stock or emergency stock, surgical gowns were contaminated because of manufacturing problems. 9.1 million of them, unusable.

As ventilators have been shipped from the strategic stockpile, the one hitch, thousands do not work. If we have equipment we need to do a proper maintenance. Maybe, we need to cycle the ventilators out into use to keep them working and running, even something as simple as face masks, and dry rot. Because I think in this case, the expiration date was… Yes, it says here, “10 years ago.”

If piling up inventory is not a sufficient or ideal strategy, we think about the movie “Top Gun” — “I feel the need, the need for speed.” Instead of bringing supplies on a literal slow boat from China, can we have supply chains that are faster like a speedboat, not just fast but agile?

It's not just a boat that can go in a straight line, but a supply chain that is a boat that can change directions quickly. I think that's part of the history with Toyota Supply Chain. After the earthquake and the tsunami, there were problems, and people blamed just in time.

In 1997, there was a brake parts plant fire that destroyed their capacity to produce an important valve for Toyota vehicles, because of Toyota's “just-in-time inventory” ran out in just one day.

This could have devastated Toyota supply line, but fortunately, one of the suppliers was able to retool and start manufacturing after just two days. To me, that's agility. Some of those points Toyota's relationships with their suppliers that allow that fast response. There's a lot of agility taking place right now.

Existing ventilator companies are working really hard and, hopefully, using Lean methods to ramp up production. They can add hours. They can add shifts. They can work 24/7. They probably need to space out their people properly. But, there's a certain limit to how much each manufacturer can ramp up, especially when they point to their own supply chain issues.

We have other companies stepping in that never made ventilators before Tesla has been designing a ventilator that's powered by their car technology. General Motors and other automakers are partnering up with medical device companies to work together to ramp up ventilation. Again, it's not just the assembly. It's the supply chain abilities that companies like GM have.

In the UK, Dyson, very quickly designed and is planning the manufacturer ventilators. It's great to see this type of agility. Agility might also mean in this day and age, moving supply to where it's needed. Thankfully, the COVID-19 wave is not hitting all countries, all cities, or all states at the same time.

There are cases and situations right now where Upstate New York, Rochester, Syracuse can send ventilators to New York City where they are much more greatly needed right now. We might move supply from state to state or from strategic stockpiles to where it's needed now.

Keeping in mind where it's needed next week or next month, might be someplace different so we can have agility in supply chain design or agility in our ability to react to shortfalls. The final thing I want to cover here in this gets a little bit more practical, how to that even in good times in normal situations. I think there's a myth that kanban means no inventory.

Coming back to Mr. Ohno he talks about the “supermarket system” that was adopted in the machine shop around 1953. A supermarket system is a strategically designed store of inventory, because one piece flow is not yet possible. Now, there are limits to prevent inventory from going to infinity, or to some number that's larger than what's needed.

Toyota put in a lot of effort to make this work. They call this the Kanban system. Back when I worked in manufacturing, I saw very Lean organizations, auto suppliers that would use a supermarket, because they couldn't do one piece flow for example, various molding machines to various assembly cells.

They couldn't do one piece flow. They couldn't do one container flow. Even if they were working on reducing the change overtimes on the molding machines, there was some batch size greater than one that was necessary. The thing that buffers the flow is called a supermarket.

Assembly cells may use a tubing Kanban system to pull from the supermarket as needed. Then, the supermarket may use kanban cards that go back to molding machines that get sequenced and leveled for the production plan that refills the supermarket. This might not be ideal, but it may exist even for a very long time within an organization. We would describe as Lean.

In hospitals, we might have kanban flow where a laboratory bench pulls supplies from a stockroom using a two-bin Kanban system. Then, when inventory gets down to a certain level, a kanban card may trigger a purchase from a supplier or a distributor, that distributor… There could be more legs in this chain.

Supermarkets and kanbans can work well when we have stable production or stable demand. If you look at something called a Reorder Point Kanban, in theory, in a perfect world, here's how it would work. Inventory would go down, and then right as it hits zero, more inventory would arrive, and we would see a sawtooth pattern over time.

Now, we can't wait until we get to zero to panic and order more. We set something called a reorder point, and then we determine a real order quantity. One of the important things here is to look at the lead time for getting more. The reorder point is basically the expected demand over that replenishment lead time.

If it takes two hours to get more supply from a stockroom, our reorder point can be relatively low. If it takes two months to get more supply from China, our reorder point would have to be higher. Now, in real life, demand is never completely perfectly flat.

There may be times, unfortunately, where we would have run out before more inventory arrived, or it may have taken them longer to get that supply that we ordered. When there's demand variation, or where there's lead time variation, we build in something called safety stock. That safety stock protects us against high demand or slow delivery.

There are judgment calls here. How much do we want to lower the water to expose rocks in our supply chain? If the risk of running out is life or death, my recommendation would be to err on the side of more safety stock.

There are certain supplies that might not be life or death, and we would treat those differently. Our reorder point becomes our demand over the expected lead time plus some level of safety stock.

In general, how would we determine kanban quantities? We'd asked, “What's the usage rate? What's the lead time to get more?” Then, most importantly, is there any usage variation? The question that I've always used when planning and setting up effective Kanban systems is, what's the worst case usage during the replenishment lead time? Can this be predicted perfectly? No.

Can this always anticipate the 100-year rare pandemic? Maybe not. This is where we need strategic planning. We need foresight. We need a risk analysis, not just an easy devotion to low inventory or an unreasonable devotion to low inventory.

In summary, before we go into Q&A, when times are good, just-in-time rarely means zero inventory. Even in a Lean system, when we have demand variation and the cost of stock outs is high, we need safety stock. Sometimes, we need what might be called emergency stock, but the question now is, whose job is it to store and move it? We don't need every hospital to hold three months of 60x demand.

This is where the idea of cooling variation and this gets into inventory theory. There is good thought between strategic stockpiles, whether that's at a regional or a state, a national, or maybe even a global level. I think another lesson is not just focusing on inventory, but realizing we're well-served by shorter lean times. That's something we might want to rethink in the future.

Lean provides frameworks, not easy answers. One thing I deeply admire about my friend, Dr. Sami Bahri, the dentist, is that he's not only read the books of Ohno, and Shingo, but he didn't try to blindly copy. He put deep thought with his staff and his employees about what do these frameworks and principles mean to us?

I would suggest — the boundaries of this may be a judgment call — do what makes sense, and then study and adjust. I think this experimental mindset, this PDSA approach is really more the core of TPS and Lean, then is low inventory.

With that, I want to thank you. The slides, the links, and the videos, a lot of what I mentioned in my talk can be found at markgraban.com/jitmyths. With that, Peter, hopefully, we have some questions, so you and I can have some discussion…

What do you think? Please scroll down (or click) to post a comment. Or please share the post with your thoughts on LinkedIn – and follow me or connect with me there.

Did you like this post? Make sure you don't miss a post or podcast — Subscribe to get notified about posts via email daily or weekly.

Check out my latest book, The Mistakes That Make Us: Cultivating a Culture of Learning and Innovation:

Mark, Thanks for making this a priority, and doing such a thorough job of providing context. Lean systems should not bear the brunt for shortfalls, as we know scapegoating is job one in many instances currently. It would be tragic to not only suffer a catastrophe like Covid-19, and then also lose the credibility and capabilities of Lean to help solve them.

Thanks, Joe. I wish more organizations appreciated the planning and problem solving aspects of Lean, rather than just chasing low inventory.