I'm writing this on Tuesday morning in Dublin, Ireland, where I have been since Sunday morning. It's my first visit to the Emerald Aisle and it has been a very nice experience. After previous stops in Zürich and the Netherlands, I was invited to facilitate a “master class” for a Lean healthcare group here in Dublin. I will also have the opportunity to visit my fourth hospital in three countries these past ten days. I'm traveling home to Texas as this post auto publishes on Wednesday morning.

Yesterday, I visited the Guinness Storehouse in Dublin. I like Guinness well enough, but I don't drink it regularly. But, still, it's so strongly associated with Ireland… and my host professor encouraged me to go, so I did.

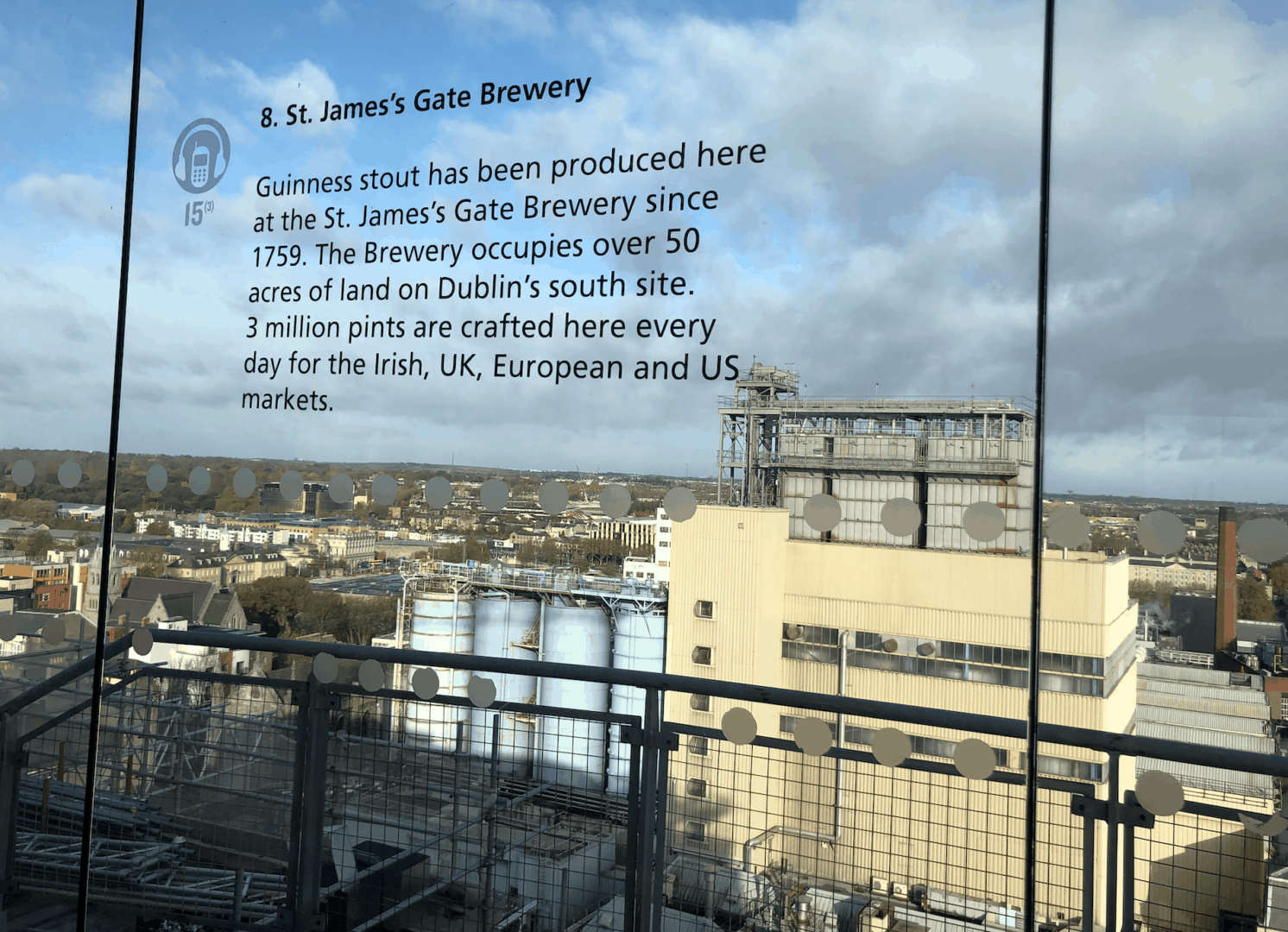

Unfortunately, they don't allow visitors into the factory, for health and safety reasons. I was able to visit a working distillery in Dublin on Sunday (Teeling's), however. Anyway, I walked past the brewery on the way. This is a photo I took from the observation level (aka, bar) at the end of the tour:

The Storehouse provides a pretty good education about beermaking and the process. Making beer is pretty much the same as whiskey making, up until the point when brewers add hops to their “wort.” Whiskey is basically distilled beer, of course (minus hops).

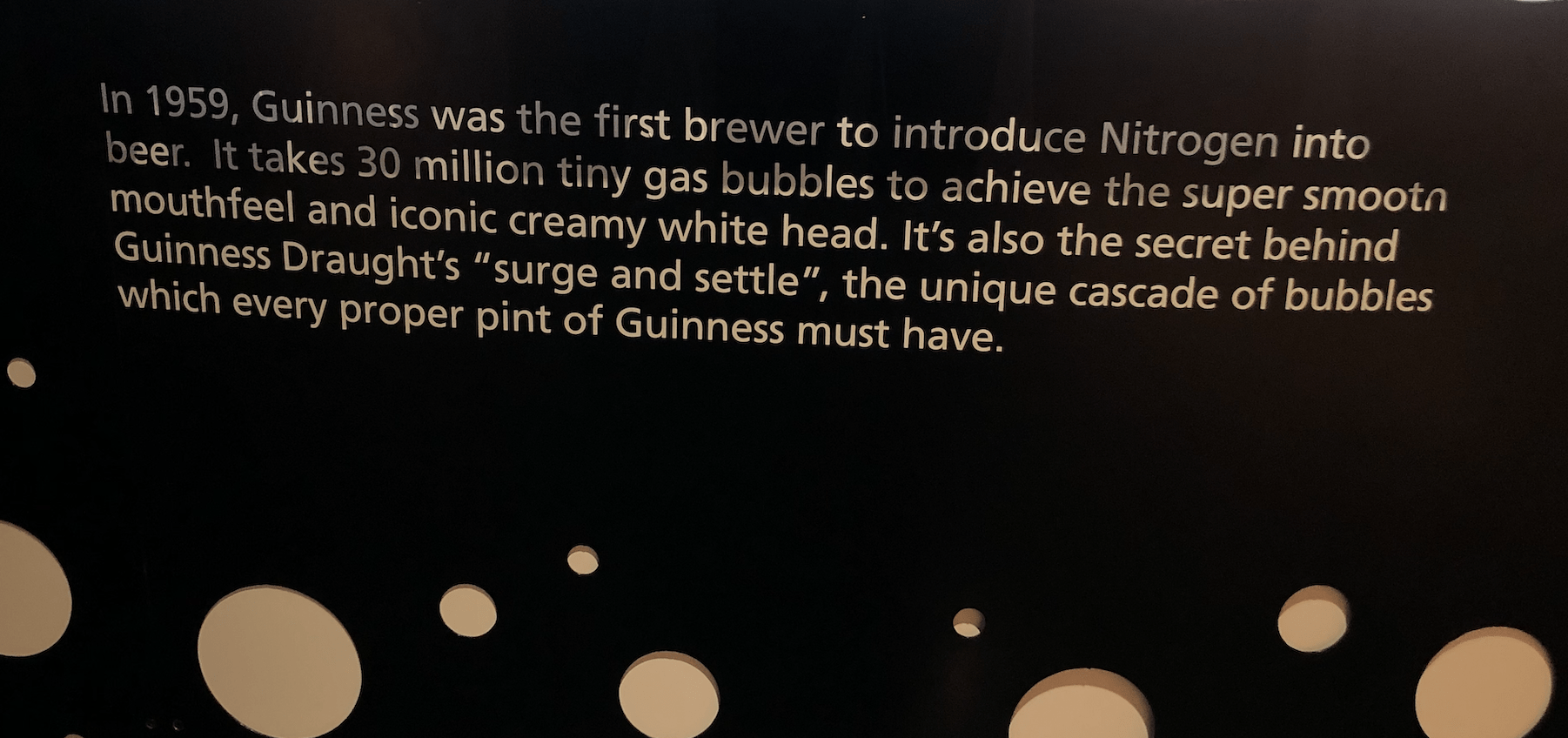

If you've had a Guinness (the main stout that they are most closely associated with), you know that the creamy mouthfeel comes from nitrogen gas (not carbon dioxide). If you've had a “nitro cold brew” coffee at Starbucks or elsewhere, you've experienced the mouthfeel of the drink and you've seen the cool way the bubbles move around in the glass after pouring (more about that later).

One thing I learned during the tour was that nitrogen was not added to Guinness until 1959. The stout was first made in the 18th century (see more in this PDF history facts sheet from Guinness).

Michael Ash is given credit for this innovation — he was originally a mathematician at Cambridge University, go figure, before becoming a brewer at Guinness in 1951.

From the display:

“At this time, carbonated draught beer was popular, yet Guinness, unlike most beers, was too lively and couldn't be draughted using CO2 alone. Ash became fascinated with solving this problem and relentlessly pursued a solution. Ash discovered a mix of CO2 and nitrogen… transformed the beer.”

Toyota, of course, talks about the importance of “challenge” and the “relentless pursuit of perfection” (that's also a Lexus marketing tagline).

I'll bring things back to Lean in healthcare. Sometimes, people become fascinated with solving important problems (like patient safety, injuries/harm, and death due to preventable errors). Invoking President John F. Kennedy, we work to solve these problems, not because they easy… but because they are hard (and important).

Many hospitals these days talk about “transformation” efforts — that's a challenge that requires relentless pursuit — perseverance is necessary.

Now, at the end of the tour, you get to go upstairs to a bar that's seemingly the tallest building in the area. It has a fantastic view and it was very sunny that morning (it was a 9:30 AM tour and I was having this pint of Guinness at 10:30 AM or so). I wasn't working that day.

Here's a photo of the bar… after a second tour member arrived (the Storehouse tour is self guided, so we don't end up arriving in big batches, I guess):

The bartender poured a Guinness, following the process that's documented in the Storehouse tour display (click for a larger view):

I'm quite certain she followed the standardized work… but I wasn't auditing her.

The pint looked beautiful to me. But, one of the other bartenders saw it and, from a few feet away, said something like:

“That pint's not perfect…”

He came to check it out. He seemed to be more experienced, and perhaps he was like a Toyota “team leader,” if you will.

He thought the head didn't look right. He checked out the tap, pulling on it to start pouring some into a fresh glass.

“Listen… there's no sound.”

He went to another tap nearby and poured. There was a noticeable hiss that wasn't heard on the other one.

The original bartender poured a pint from that new tap, while the team leader immediately investigated the other one. I'm sure he wanted to resolve that problem before the bar got crowded.

The team leader determined that something was wrong with the tap nozzle. So, he replaced it and it was fixed. That was what I could call a “short-term countermeasure.”

He then went on to say something like, “It must have been dirty.” I don't know if there was further investigation to see why it got dirty… or why it perhaps wasn't cleaned at the end of day Sunday. It might be helpful to look for a longer-term countermeasure — a process improvement that could prevent future problems like this.

I didn't mind… my pint was delayed just a bit and I enjoyed observing all of this.

Here are some photos of what they thought was a “perfect pint.” First is how it looks after the initial pour that is supposed to stop 3/4 of the way up the glass. The second photo is the Guinness before it has fully settled and turned black as the gas settles.

I appreciate the pursuit of perfection and the problem solving that's involved. I can only imagine how many pints are poured at the Guinness Storehouse… it's really difficult to reach a point of perfection. Toyota isn't perfect. But the relentless pursuit is what matters.

Sláinte! Cheers!

What do you think? Please scroll down (or click) to post a comment. Or please share the post with your thoughts on LinkedIn – and follow me or connect with me there.

Did you like this post? Make sure you don't miss a post or podcast — Subscribe to get notified about posts via email daily or weekly.

Check out my latest book, The Mistakes That Make Us: Cultivating a Culture of Learning and Innovation:

Here is the discussion about this on LinkedIn:

Believe it or not, my local Buffalo Wild Wings always pours me a perfect pint.

Nice read. It’s not always easy to find a #PerfectPint , even in Ireland, but especially here in the States…unfortunately.

Sláinte!