When we have really sticky, complicated problems (like the widespread healthcare patient safety and quality problems), I think it's interesting to think about problems in the following terms… for a particular problem, which is true?

- It can't be solved (in general)

- That organization can't solve it (don't know how?)

- They won't solve it

- They don't need to solve it

When we look at patient safety, there are many examples that show improvement is possible. So, it comes down to a question of “can't, won't, or don't need to?”

In the Lean approach, asking “why?” happens a lot. Why should we improve? Why is that problem occurring? We might ask why five times (or many times).

We can also ask, “Why not?” in a way that triggers and encourages improvement, innovation, and a break from “the way we've always done it.”

It's tempting for people to say, “We haven't been able to solve that problem before… therefore, it's unsolvable and we shouldn't feel bad about it.”

It's not solvable? Why not?

It's a challenge… but that's good.

Toyota says their continuous improvement culture is based on principles including “Challenge, Kaizen and Genchi Genbutsu.”

In a recent talk that I gave, I shared some examples of organizations that said “why not?” in response to challenges.

If we believe safety is important, we need to ask more “why not?” questions, perhaps.

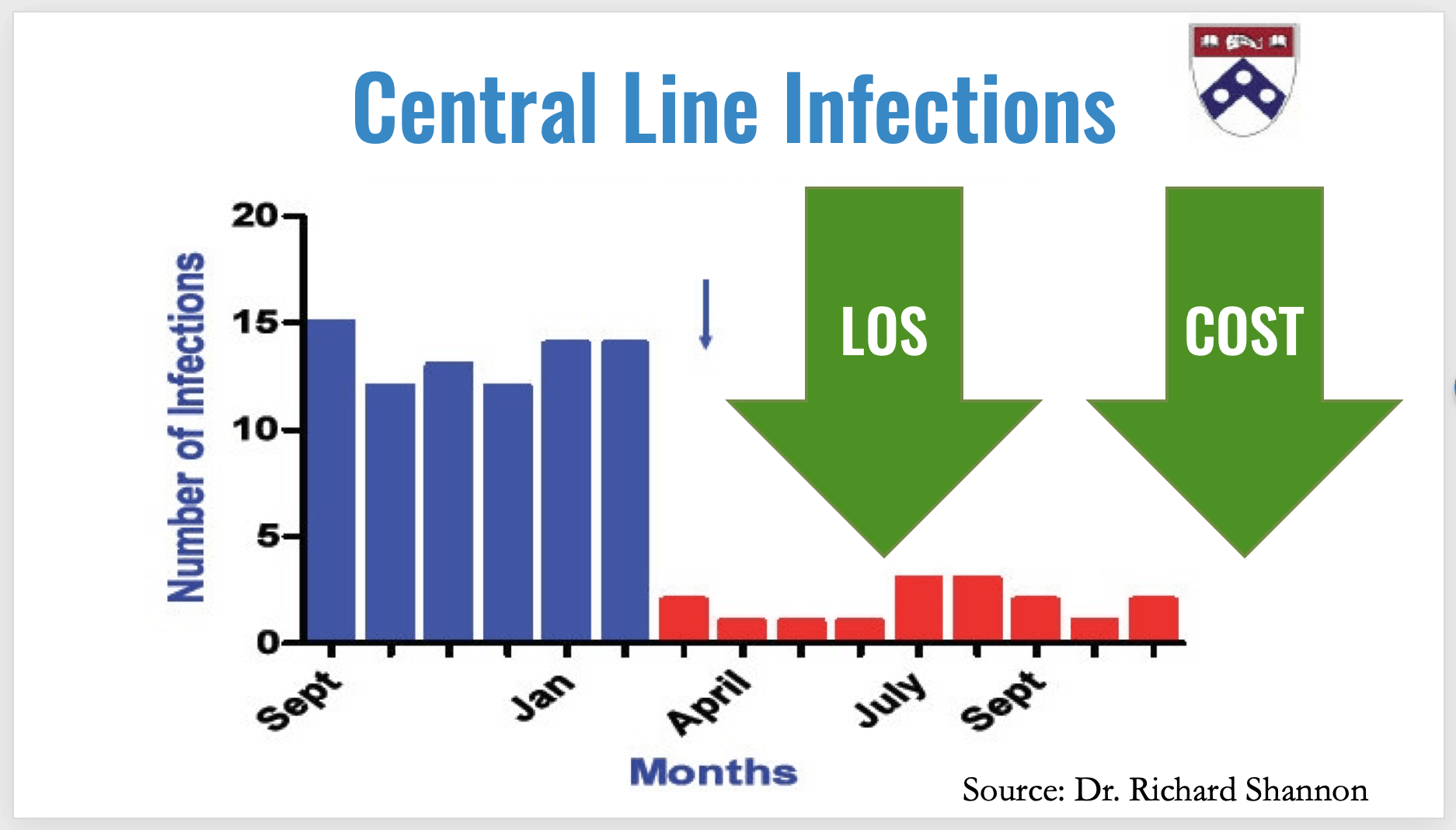

Why not reduce CLABSI (Central Line Associated Blood Stream Infections) rates? It's possible, as Dr. Rick Shannon has demonstrated many times (hear my podcast with him). When the number of infections went down, so did the average length of stay… cost went down too.

So, other organizations could ask “why not?” or “why can't we do this too?”

As you can see in this YouTube video, Park Nicollet asked “why not bring all cancer treatment to the patient?” There are good reasons why they can't bring radiation treatment to the patient, but they figured out how to bring everything else to them.

One “why not?” challenge was involved having to fit an exam table and a reclining chair into each private patient treatment room. The rooms would have then been too large to make the model work.

“Why not have a recliner that goes flat and also raises up to become a proper exam table?”

Instead of letting the challenge be a barrier, they figured it out. They invented a chair that could also be an exam table. Problem solved. Challenge defeated.

I found some other “why nots?” when I visited Sweden a few years back. In the name of improving patient flow and outcomes for heart attack patients, they asked, “Why not have the EKG done in the ambulance?”

They also asked, “Why not send the EKG electronically so we can review it before the patient arrives?”

They also asked, “Why not send some patients directly to the cath lab if the EKG results indicate that?”

They figured that all out.

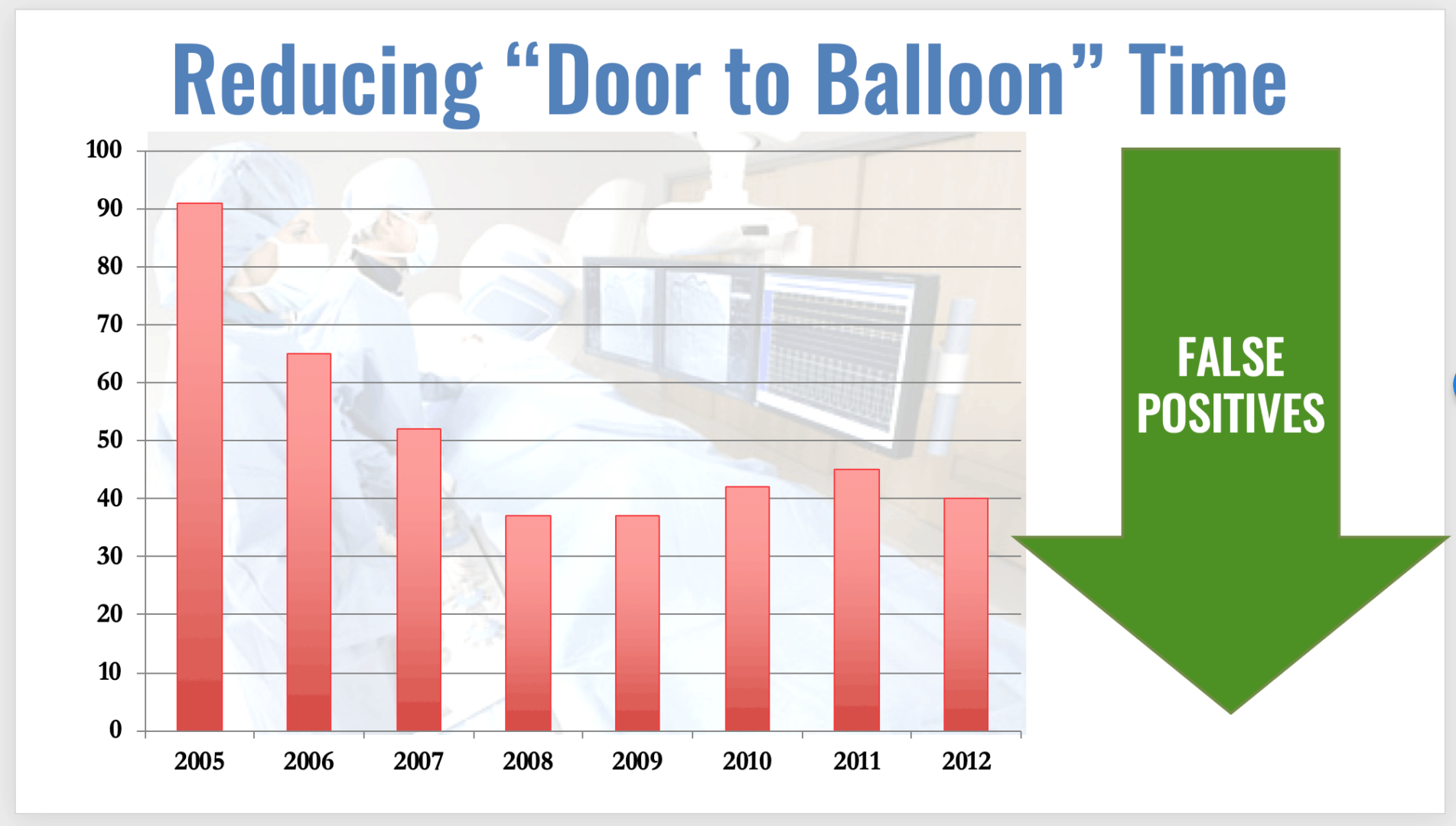

When ThedaCare reduced their “door to balloon” time for heart attack patients, they asked things like, “Why not let the E.R. docs read the EKG instead of waiting for a cardiologist at 2 am?” Oh, they're perhaps not trained as well? Why not train them so they can do it?

ThedaCare saw reductions in those times and a reduction in “false positive” rates, meaning quality had also gone up.

Back to the hospital in Sweden, they were facing delays in aspects of inpatient cardiac care, as I blogged about then.

“At St. Göran, the cardiology unit was sending patients to a centralized department for ultrasound testing and for stress testing. It was “a team-based decision” to put a small unit of capacity right in the cardiology space. They now, with Lean thinking, have their own ultrasound machine and a treadmill. They did this to avoid patient movement and delay.”

Why not?

Based on that experience, the unit started to question the delays incurred in sending patients from cardiology to get pacemakers implanted in the operating rooms (a centralized department, as in every hospital). The centralized unit creates scheduling complexity — an increase in emergency patients or a delay in outpatient cases might hamper flow of patients from the cardiology unit.

“So the team decided to build a dedicated and specialized small operating room in the cardiology unit. They now do pacemaker implantation right there — a shorter, more simplified patient flow.”

Which is more powerful? “We've never done it that way” or “why not?”

At Franciscan St. Francis Health, the NICU faced the sad challenge of a baby getting a pressure ulcer on the back of their head. They asked, “Why not create a mattress cover that could be designed in a way that allowed it to be changed without moving the baby completely off of that super-heavy special mattress?” They solved that challenge. Why not?

One final challenge I think about is empty hand sanitizer dispensers… something I find way too often.

Making the hand sanitizer readily available…. which type of problem is this?

- It can't be solved (in general)

- That organization can't solve it (don't know how?)

- They won't solve it

- They don't need to solve it

I refuse to think that can't be solved. So, which situation is it?

Why not solve that? Why not find a more creative way?

As I've proposed before…

Facing important challenges (and making progress) isn't easy… but it's got to feel better than being self-defeating about what can't be done.

What inspiring “why not?” situations have you seen in healthcare?

What do you think? Please scroll down (or click) to post a comment. Or please share the post with your thoughts on LinkedIn – and follow me or connect with me there.

Did you like this post? Make sure you don't miss a post or podcast — Subscribe to get notified about posts via email daily or weekly.

Check out my latest book, The Mistakes That Make Us: Cultivating a Culture of Learning and Innovation:

LinkedIn Discussion:

I particularly like Brian Buck’s comment about the phrase “how might we….?” I agree that’s a better phrase…

I’ve blogged about that before:

https://www.leanblog.org/2017/06/power-might-____________/