tl;dr: In this post, Mark shares insights from a video featuring Nampachi Hayashi, a senior advisor at Toyota, discussing common misunderstandings about the Toyota Production System (TPS). The blog post aims to clarify misconceptions and provides notes that supplement the video content. It serves as a valuable resource for anyone seeking an authentic understanding of TPS from a credible source within Toyota.

Thanks to Pablo Alvarez Flores, who posted this video on LinkedIn with an invitation for me to share my comments and reactions. There's a lot to dig into, but this post will focus on the theme of misunderstandings.

Nampachi Hayashi – Toyota Production System and The Roots of Lean from Goldratt Consulting Ltd. on Vimeo.

I'm writing this post as I watch the video, which was shared on Vimeo by Goldratt Consulting Ltd. (yes, Goldratt as in The Goal). It's a talk given by Nampachi Hayashi at the “Building on Success 2018 Conference.”

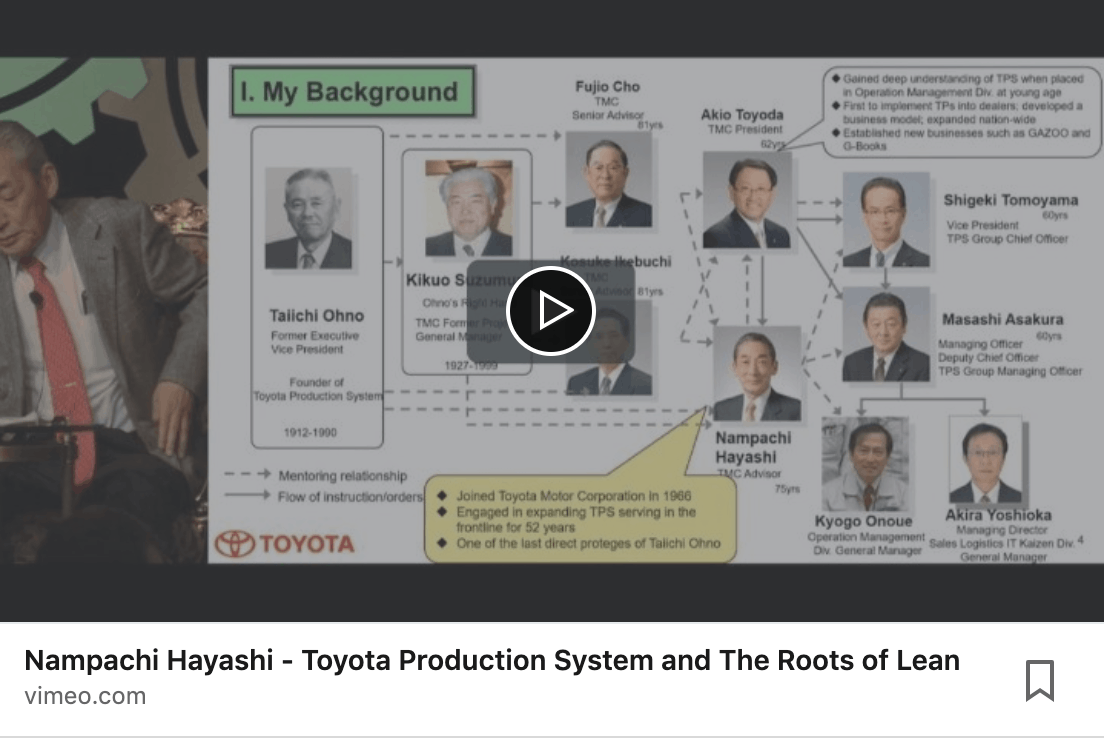

About Mr. Hayashi:

“He served as a senior technical executive of Toyota, and from

2009, has sat on the company's board of directors. Mr. Hayashi is a member of the “Productivity Improvement Citizens Advancement Council” advanced by Japan's Prime Minister Shinzo Abe. Mr. Hayashi is well-known around the world for his humor and liveliness to explain the essence of the Toyota Production System (TPS) as it applies to various industries.”

As Mr. Hayashi shares in the video, he joined Toyota in 1966 and was “engaged in expanding TPS serving in the frontline for 52 years” and was “one of the last direct proteges of Taiichi Ohno.”

Mr. Hayashi was a sensei to Michael Ballé‘s father, as he wrote about here.

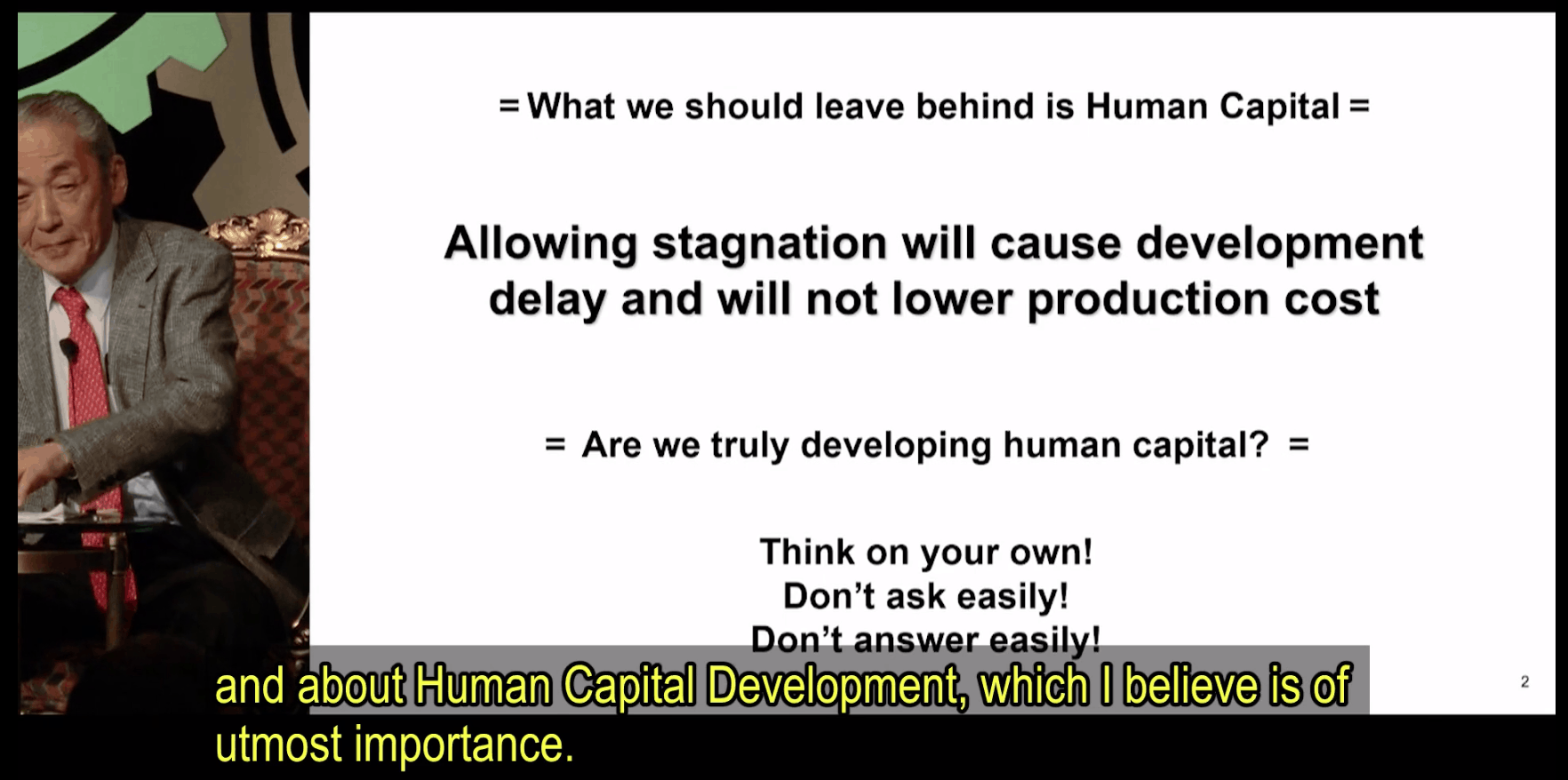

Even before introducing himself, Mr. Hayashi talks about the importance of developing human capital in the organization:

This is a Toyota theme (Human Resource Development) that I learned a lot about on my last trip to Japan (see a post and a podcast about this).

Mr. Hayashi says that current CEO Akio Toyoda “studied the Toyota Production System on-hand under my direction.” He points out that none of the current board members (nor the CEO) had the opportunity to be directly mentored by Mr. Ohno, but “his legacy has been passed on.”

Mr. Hayashi showed a photo with Eli Goldratt and said Goldratt honored Ohno as “my hero” — an interesting intersection of TPS and TOC (the Theory of Constraints).

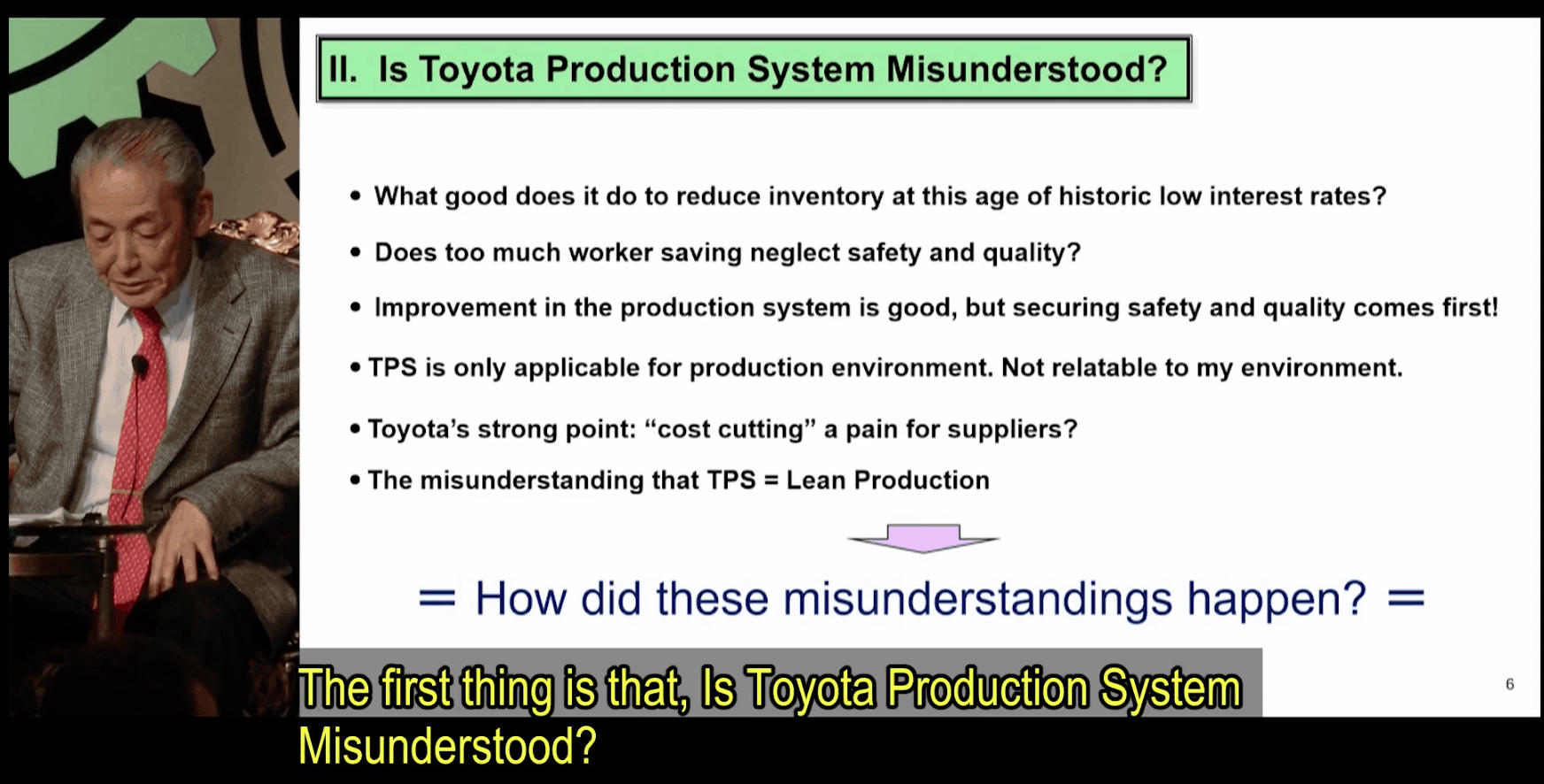

Is Toyota Production System Misunderstood?

He seems to answer his question on the bottom of the slide by asking “how” these misunderstandings happen. I'll add notes below… and some of the subtitle translation language is more clear than the wording of the slides, in some cases:

- “Why reduce inventory in an age of low interest rates?”

- “Do we neglect safety and quality when we have worker savings?”

- “TPS is only applicable for a production environment. It's not relatable to my environment.”

- “The misunderstanding that TPS is an improvement method born in a production plant.”

He introduced those misunderstandings, but I wish he would have elaborated more. Of course, Toyota places a high priority on safety and quality. He didn't address the idea of TPS being used in healthcare or other industries… but he did have a lot of interesting things to say.

Mr. Hayahsi says that TPS was first called various names like “Ohno System,” “Kanban System,” or “Later-process Pull System,” but was unified under the name Toyota Production System “with Mr. Ohno's approval.”

“This was the beginning of the misunderstanding!!”

Mr. Hayashi says the name “should have been TPS = Toyota Process Development System.”

“It is not an improvement method born from gemba. Solely a mechanism for Genka Teigen and Human Capital Development.”

He says Genka Teigen literally translates to “cost reduction.”

Jidoka and Just in Time

Mr. Hayashi talks about the “two pillars that support the TPS:”

- Jiokda (“autonomation,” meaning “intelligent automation”)

- Just in Time

This is not new if you have studied TPS. Here is Toyota's corporate web page about TPS.

“By applying these rigorously, [cost reduction] will be made possible.”

This is in line with what I was taught about built-in quality and improved flow leading to lower cost… as a result. Cost reduction isn't the primary lever that's pulled (as we see attempted in so many Western companies, including hospitals)… it's a result. Simple cost-cutting might not lead to better quality and flow (it's often quite the opposite that happens). But better flow and better quality always leads to lower cost, in my experience.

“And going through this process itself will develop human capital.”

Mr. Hayashi says it's difficult to explain the essence of jidoka so they keep the Japanese word and attempt to explain it.

He says there are two goals of jidoka:

- “to build good quality into each process”

- “not make the operator an assistant to the machine”

Back to the lower cost that results… in an interesting twist, after saying “Genka Teigen” literally translates to mean “cost reduction,” he says, “Toyota's Genka Teigen is NOT Cost Reduction.” It doesn't mean “to buy things cheaper.” It's defined as “to make things cheaper.”

He adds:

“There is no magic method. Rather, a total management system is needed that develops human ability to its fullest capacity to best enhance creativity and fruitfulness, to utilize facilities and machines well, and to eliminate all waste.”

Mr. Hayashi mentioned Mr. Ohno and the idea that Toyota works with suppliers to help them produce at a lower cost so the supplier can make more money. Compare that to the traditional “Big 3” approach of just demanding lower prices from suppliers.

He says:

“Quality is the basis of the Toyota Production System.”

He elaborates to say it means “good product at low cost in timely manner.” Compare that to the common misunderstanding that thinks TPS is only about cost (or only about efficiency or speed). “Quality must be built in during each process” and that's accomplished when work “automatically stops when problems occur.” And, because production stops “when the work is done” (when demand is met), then “less workers are required.”

I also like his phrasing about Just in Time… shorter distances and smaller batches mean less lead time. He adds:

“Large Lot is the Villain that Lengthens Lead Time”

Hence the need to reduce setup times instead of just trying to forecast sales more accurately at longer lead times. Better flow, of course, helps support better quality.

Making me Think About Healthcare

Mr. Hayashi adds two points that make me think about healthcare.

- Customer first: “customer will not come unless we provide quality products”

- My comment: patients too often come to hospitals with the assumption that quality is good (or equally good) when that's not always the case. Better quality might not be rewarded in healthcare the same way the market rewards quality in the auto industry.

- “Tight financial situation does not allow any defects”

- My comment: in healthcare, the defects are too often hidden or get reimbursed anyway, meaning there's often less of a financial incentive to reduce defects (but there should be a moral reason to do so, since healthcare says they are different).

Is your organization willing to be motivated by a rallying cry of “zero defects” (or perhaps “zero harm” for healthcare), as Mr. Hayashi talks about?

In the video, which I will probably continue blogging about, Mr. Hayashi does not seem to directly answer his question about where misunderstandings come from. What are your thoughts on this?

Does your organization have misunderstandings or incomplete understandings about TPS or Lean? What can we do about this?

Please scroll down (or click) to post a comment. Connect with me on LinkedIn.

Let’s build a culture of continuous improvement and psychological safety—together. If you're a leader aiming for lasting change (not just more projects), I help organizations:

- Engage people at all levels in sustainable improvement

- Shift from fear of mistakes to learning from them

- Apply Lean thinking in practical, people-centered ways

Interested in coaching or a keynote talk? Let’s talk.

Join me for a Lean Healthcare Accelerator Trip to Japan! Learn More

The most significant thing is in Slide 6: “The misunderstanding that TPS = Lean Production.” I am one of several people who pointed out this fact (e.g. https://bobemiliani.com/is-lean-the-same-as-tps/) and was attacked and stigmatized.

Womack and Jones should correct that misunderstanding, provide relevant details as to exactly how that misunderstanding came about, and explain why it remains uncorrected after more than three decades. Also, slide 7 says “[TPS] is solely a mechanism for genka teigen and human capital development.”

If TPS is a mechanism, it is not a strategy, so what makes Lean a strategy (see https://bobemiliani.com/book-review-the-lean-strategy/)? Ballé et al. should explain that, also in detail and clear up any misunderstandings. It has long been my view that Lean movement leaders have taken advantage of the misunderstandings to their benefit and to the detriment of Lean practitioners.

Bob – Mr. Hayashi didn’t elaborate (and I wish he would have), but the subtitle says, “The misunderstanding that TPS is an improvement method born in a production plant.”

Arguably, he’s taking issue with the “production” label, not the “lean” label. He takes issue, again, with the word “production” when he says TPS should have been the Toyota Process Development System.

Toyota’s own website doesn’t take issue with the term “lean manufacturing.”

Mark – When I asked Mr. Nakao about Lean, he said: “I don’t know what that is.” Clearly not the same. Also, de-emphasis of “production” appears to me to be an ex post facto rationalization. In Toyota’s web site, the words “referred to” does not suggest sameness.

Mr. Nakao is not Toyota and he’s not their spokesman. The Toyota website suggests more sameness with Lean than, say, Six Sigma or other methodologies that are clearly not the same as TPS.

Mark – Nakao-san worked at Taiho Kogyo, a wholly owned subsidiary of Toyota (eventually becoming plant manager). He was a charter member of Toyota Jishuken and Ohno’s assistant at one time. As with Nakao, Mr. Hayashi is not a Toyota’s spokesman. Both are long retired.

Mr. Hayashi said he graduated from college in 1966 and worked for Toyota 52 years. Fact check: that’s not “long retired.”

This great video took me back to the late 1980’s when I first started learning about TPS when I was a Divisional VP. That was many years before the term “Lean” became popular around 1996. Unfortunately, much has been lost since that time.

One very important concept that has all but disappeared is the key role that “Lead Time” plays in making TPS (or Lean) work. But Hayashi stresses the importance of Lead Time throughout the first half of his presentation. That was music to my ears. Here are a few quotes from Hayashi’s presentation:

– “Lead Time decides the level of Just-In-Time”

– “Short Lead Time becomes a weapon to differentiate”

– “Shortening the Lead Time is nothing but a mechanism to progress the improvement in Human Development”

An underlying principle behind TPS/Lean is the systemic creation of the shortest possible lead time for the continuous flow of materials and information in order to generate the highest quality and lowest cost. Yes, high quality and low cost are the “result” of reducing Lead Time. And Lead Time is reduced by improving flow by removing waste (or “stagnation” according to Hayashi). And that can’t be done without the full participation and continuous learning of the people closest to the gemba.

I thought Hayashi outlined these concepts very well.

Yes, those are really important points. We can also think about this in healthcare… the shortest possible treatment lead time for the continuous flow of patients, materials, and information… to generate the highest quality and lowest cost care.

Here is a story from the new book “The Lean Sensei” by Michael Ballé, et. al.:

Hi Mark,

I hope you’re doing well. From our recent Jun Agile Denver Kanban CoP monthly meetup that I facilitate, a link was provided to your post and this very helpful video by Mr. Hayashi. As you mentioned above, there are some statements from the slides that are a bit hard to understand even with the accompanying subtitles.

Two in particular I’ve captured below (from around the 00:57:00 mark) I’d like to run by you and see if my interpretations make sense or if you had a different take.

1) Entrust means to give authority while taking responsibility. Based on my Toyota Kata reading I interpreted this to be along the lines of to give the authority to those you’re coaching to make changes, etc., while you take responsibility for the results, if they didn’t learn, you didn’t coach. Does this match somewhat to what you think he is saying?

2) It is important to have the “humbleness” to think on your own. Not sure on this one, but is he meaning let others think on their own, for themselves, the moment you give a challenge to them? If not, what is your take on this one?

Thanks!

Take care,

Frank

Hi Frank – Thanks for reading and commenting!

Good questions… I don’t want to try to answer on his behalf, but I would think “humbleness” would mean being humble and not thinking you have all the answers as a leader… which means getting input from the employees you are coaching.

I think one can delegate some authority without giving away responsibility for the system, as you also said. I don’t think a CEO or plant manager can delegate responsibility for employee safety (nor can a hospital CEO delegate responsibility for patient safety), but they can delegate decision making (retaining the right to coach and give input).

Great post

It seems that Hiyashi-san has passed away:

LINK

My deepest condolences to his family, friends, and former colleagues…

Comments are closed.