When we started the new year, many of us make a weight loss resolution (see my article on resolutions via “The Lean Post“).

As I've learned from my work in the business world, measuring something doesn't mean it will improve. But, a measure (like our weight on a scale) is an important component of a scientific approach to improvement. When my weight has increased, it usually happens when I'm traveling a lot or otherwise not weighing myself as often.

When I've been in a phase where I'm looking just to maintain my weight, I've found that weighing myself daily can be helpful. That said, many experts advise against weighing yourself daily because there is a tendency to overreact to each daily up or down. Some suggest weighing yourself weekly to get a better sense of a longer-term trend.

That's one approach. But, I've used a helpful method from the business world called “Process Behavior Charts” to better understand routine fluctuations in my weight, which helps me react — without overreacting — whether I'm weighing myself daily or weekly.

It's a fact of life that every measure, over time, will have variation — it's a matter of how much. How much variation, or “noise,” is normal? When we understand how much a metric tends to vary or fluctuate, we can do a better job of detecting “signals” that say our performance measure (or our weight) has changed enough to be worth reacting to.

If you have a fitness tracker or a smartwatch, look at the chart of your daily resting heart rate. It's not going to show the exact same number every day — mine fluctuates somewhat randomly between 68 and 72. I shouldn't react to or worry about every up and down that's within the typical range.

But, when I was sick with a bad case of stomach flu last August, my resting heart rate spiked to over 120 for a few hours and the average for the day was 78. I didn't need a chart to tell me that something was unusual, but it confirmed the idea that a measure only falls outside of its normal range if something has changed in a significant way — thankfully, that was temporary.

When it comes to weight, when mine is stable my daily number on the scale generally fluctuates within a range of 1.25 pounds above and below my average weight over that timeframe. I've learned not to overreact to relatively small changes over a day or two — and I don't need to radically alter my diet or exercise routine. The normal or routine fluctuation for other people might be different. Since our weight naturally varies a bit during the day, I eliminate that source of variation by weighing myself right after I wake up.

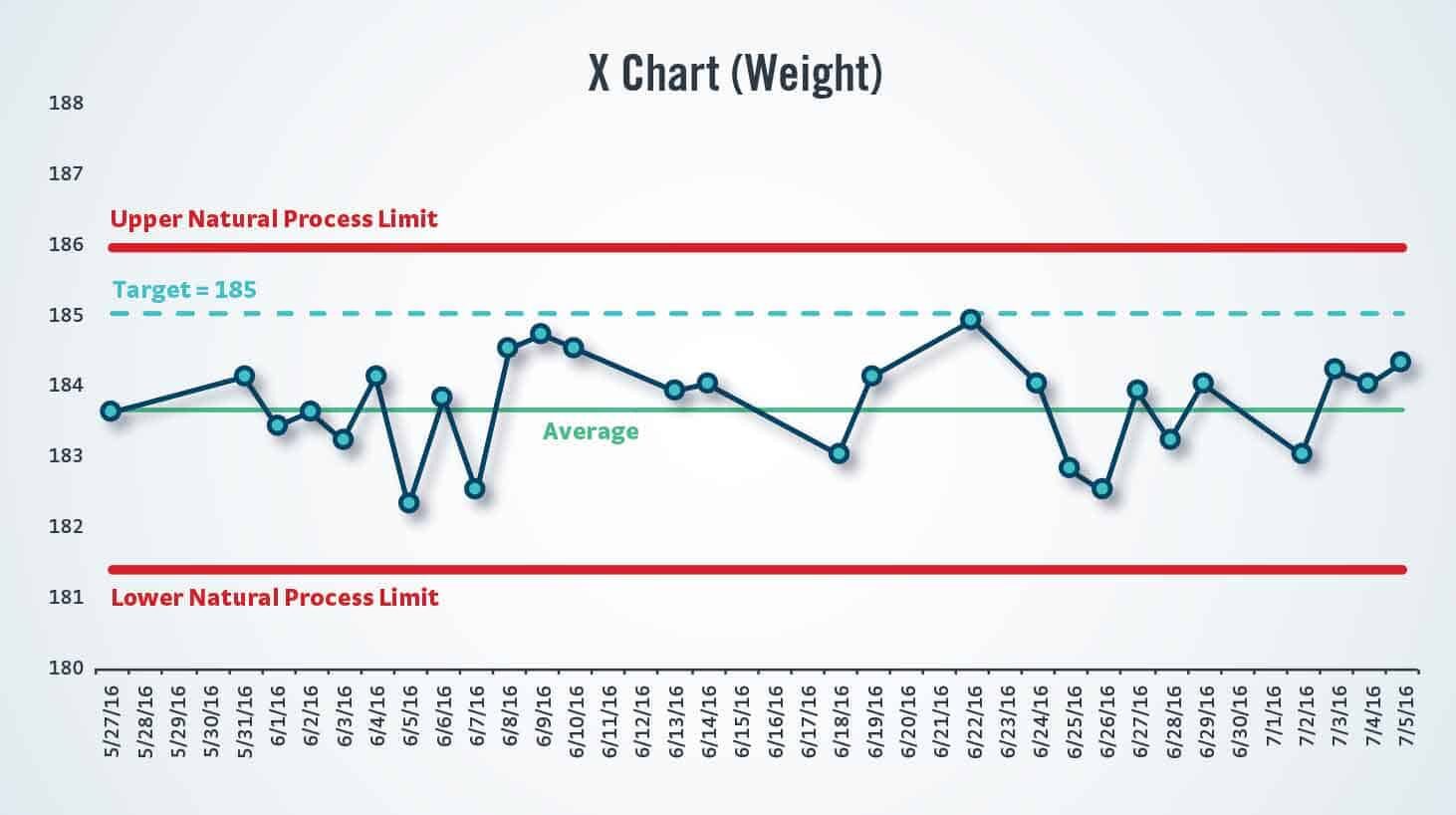

When we use a Process Behavior Chart, we use a period of baseline data to calculate the average and what are called “Natural Process Limits” — two lines that are symmetrical around the average, as shown below (images from my book Measures of Success: React Less, Lead Better, Improve More, now available in paperback:

The statistical theory behind Process Behavior Charts, as I describe in more detail in my book Measures of Success, tells me not to overreact to any single weight number that falls between the lower and upper limits of 181.4 and 185.9. There is no “root cause” to be found for any of those data points within the limits. It's nothing but noise in the data.

But, If I were trying to maintain my weight and it crept up to that upper limit, that would be a time to ask “what changed?” The statistics would say it was unlikely that my weight randomly fluctuated that high and it would be time to consider changes to bring my weight back down.

If I saw eight consecutive scale readings above the average, that's also not going to be random fluctuation. While a single number above the upper limit represents large change, the eight consecutive above-average points represent a sustained changed, even if it's small.

When I was in a period of desired weight loss — when my average weight was above my target weight — I was hoping to see a signal of weight loss instead of mistakenly celebrating fluctuations. When I was losing weight, I was looking for a relatively steady decline (trying to lose one pound a week). I used the Process Behavior Chart to help prove to myself I was making progress, as shown below:

I knew I was making sustained progress when I saw eight consecutive data points below the lower limit. That was soon followed by data points below the lower limit. The statistics and the chart proved that my weight wasn't just fluctuating. But, as my weight shifted downward, the chart and this way of thinking also kept me from freaking out about every small fluctuation upward.

I hope this method helps you separate the signal from the noise in your weight loss challenge — or in your workplace!

Here's a reader tweet:

Reading @MarkGraban new book Measures of Success.

— Don Eitel (@DonEitel) March 23, 2019

I have a certain disdain for metrics due to the ways in which they are routinely abused.

Mark brings the teachings of Deming into clear, simple language with lots of examples.

Highly recommended for leaders and change agents.

Thanks to Don for his tweet!

Please scroll down (or click) to post a comment. Connect with me on LinkedIn.

Let’s build a culture of continuous improvement and psychological safety—together. If you're a leader aiming for lasting change (not just more projects), I help organizations:

- Engage people at all levels in sustainable improvement

- Shift from fear of mistakes to learning from them

- Apply Lean thinking in practical, people-centered ways

Interested in coaching or a keynote talk? Let’s talk.

Join me for a Lean Healthcare Accelerator Trip to Japan! Learn More

I think this is a great example of how to measure things in the workplace. You can’t look at every little fluctuation and overreact to try to fix something that isn’t actually broken. There are normal fluctuations in everything no matter how small they are and you have to figure out what the normal fluctuation is. If something is wrong and you measure it, the results will most likely be dramatically outside of the normal fluctuations. Even if it is slightly outside normal fluctuations doesn’t mean something is wrong. Most of the time you will see a drastic change in what you are measuring.

Using process behavior charts to track weight loss/gain is a great application of lean practices. I have fallen victim many a time to the day to day fluctuations of weight, mistaking them for true signals of gains or losses when they were in fact just noise in the process. This usually leads me to giving up quickly on my weight loss routine on the first notice of an upward fluctuation in weight. By using a lean tool like process behavior charts, you can gain better insight into the trend that your weight fluctuations are following and give more realistic signals of true weight loss or weight gain. This is a much better method of measuring whether your weight gain/loss is being sustained or not.

Matthew — Good point about applying this to other measures. Like Chase said, a small fluctuation might not mean anything is wrong… and it might not be anything to get too excited about. A Process Behavior Chart will filter out the noise so we can find signals when they are there.

This is a great way to track and monitor your progress in any fitness goal, I think a lot of people get discouraged by not seeing progress right away, but this method makes the results a lot more encouraging, and this could also be used for weight targets for lifting, if someone was trying to increase their bench press or squat, they could use this as well, just another way lean thinkers can improve their lives

Comments are closed.