When most organizations talk about Lean, they start with the tools.

When Toyota talks about Lean, they start with people.

On my last trip to Japan, I heard former Toyota leaders repeat a phrase that stuck with me:

“We're not just a car company. We're a people development company.”

It wasn't a slogan–it was a guiding principle you could see in action everywhere we visited.

Hear Mark read this post — subscribe to Lean Blog Audio

Many companies try to copy Lean tools or practices, but they don't have the mindset of a “development company.” Is that why these organizations struggle with Lean and sometimes give up? Can organizations shift from viewing employees as a cost (and a short-term cost, at that) and, instead, view them as a long-term asset that can appreciate over time?

In our very first orientation discussion of the trip, Honsha's Barry McCarthy used the term “development system.” He didn't mean the “Toyota Product Development System.” He meant their people development system. Barry would know because he was a long-time manufacturing and HR manager for Toyota in Australia.

That's Barry on the right, with me and the rest of the Honsha team members who were part of the trip and our learning:

My Podcast with Barry:

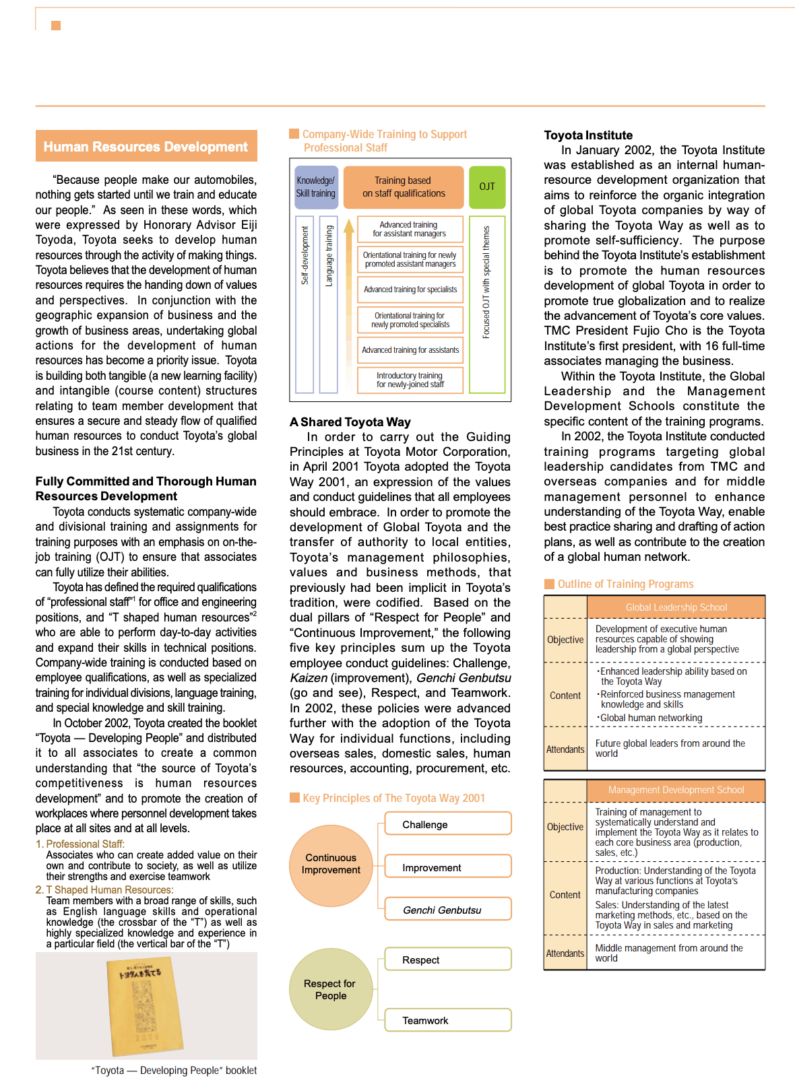

I should say Barry (and others) were part of “HRD” because Toyota calls that department “Human Resources Development,” which says a lot. Here is a Toyota PDF document about HRD.

“Because people make our automobiles, nothing gets started until we train and educate our people.”

Eiji Toyoda, quoted in the Toyota PDF

The document adds:

“Toyota seeks to develop human resources through the activity of making things.”

Toyota document

The document also says:

“In October 2002, Toyota created the booklet “Toyota — Developing People” and distributed it to all associates to create a common understanding that “the source of Toyota's competitiveness is human resources development” and to promote the creation of workplaces where

Toyota documentpersonnel development takes place at all sites and at all levels.“

This kept coming up over and over during the week. The very best organizations that we visited got the praise of being a “development company.”

On the unfortunate flip side, how many organizations around the world are using employees instead of developing them?

Why do hospitals send nurses home early instead of investing in them and developing them through training and continuous improvement activities? Shouldn't hospitals be “development organizations?” Do the best-performing and most-improving health systems merit that label?

I've often heard that Toyota places this priority on the outcomes of improvement activity, like “kaizen“:

First, people development. Second, the improvement itself.

I've heard it said that an improvement effort that results in learning, but not

During the week, Barry talked about the sad process of Toyota shutting down its manufacturing plants in Australia. Before you criticize Toyota for that, realize that the other automakers had also pulled out of Australia, deciding it was more cost-effective to import cars than it was to build them there. With the industry hollowed out, Toyota alone couldn't support the base of suppliers… they decided to leave too.

Barry talked about Toyota's commitment to developing people up to the very end. They wanted the last car ever built to be the best one they ever made. That meant, of course, treating employees more than “fairly” — it meant treating them well.

Toyota paid for career development for new careers — including people who were going to become healthcare providers and at least one who was going to become a commercial pilot. Toyota wasn't just kicking people to the curb (or however that would be colorfully said down under).

Here is an article about one plant closure:

Oh, what a feeling for 2700 axed Toyota workers

Toyota says more than 2200 employees have taken part in its job skills training program, which will continue for six months after manufacturing stops.

“Many employees have taken the opportunity to develop their skills to start their own small business, in areas as varied as nutrition, landscaping, brewing and photography,” the company said in a statement.

The article also talks about a Toyota supplier where, unfortunately, the employees weren't getting much advance notice about their futures. It sounded like they might just get fired with minimal notice. Was that not a “development company?”

Toyota would certainly have an interest in their suppliers also being development companies, since that means they would perform better for Toyota over the long term. We visited some Toyota suppliers in Japan who definitely seemed like development companies.

Barry also talked about how not all Japanese companies are “people development” companies. I've learned in previous trips that Lean is not the default culture or mode of operating in Japan. When people say “this would be easier if we were Japanese,” I don't think that's really true. Toyota has worked really hard to create this culture that many try to emulate as a “Lean culture.”

I've written about this, as has Katie Anderson:

As a final resource on HRD at Toyota, here is a journal article written by Jeff Liker and Mike Hoseus:

Human Resource development in Toyota culture

You can download the full PDF.

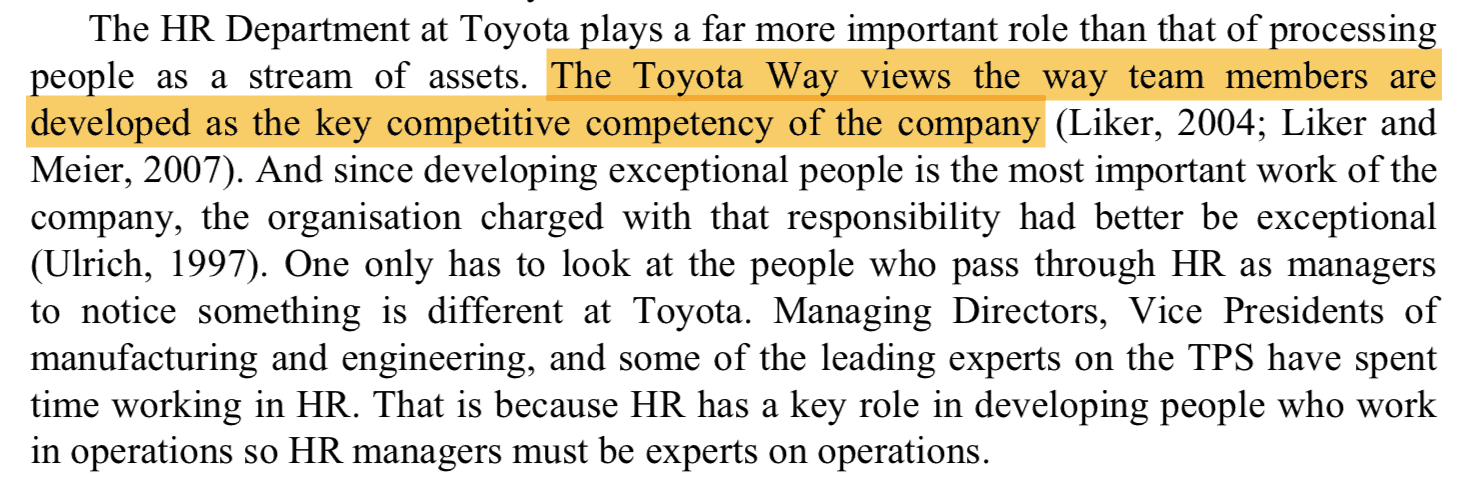

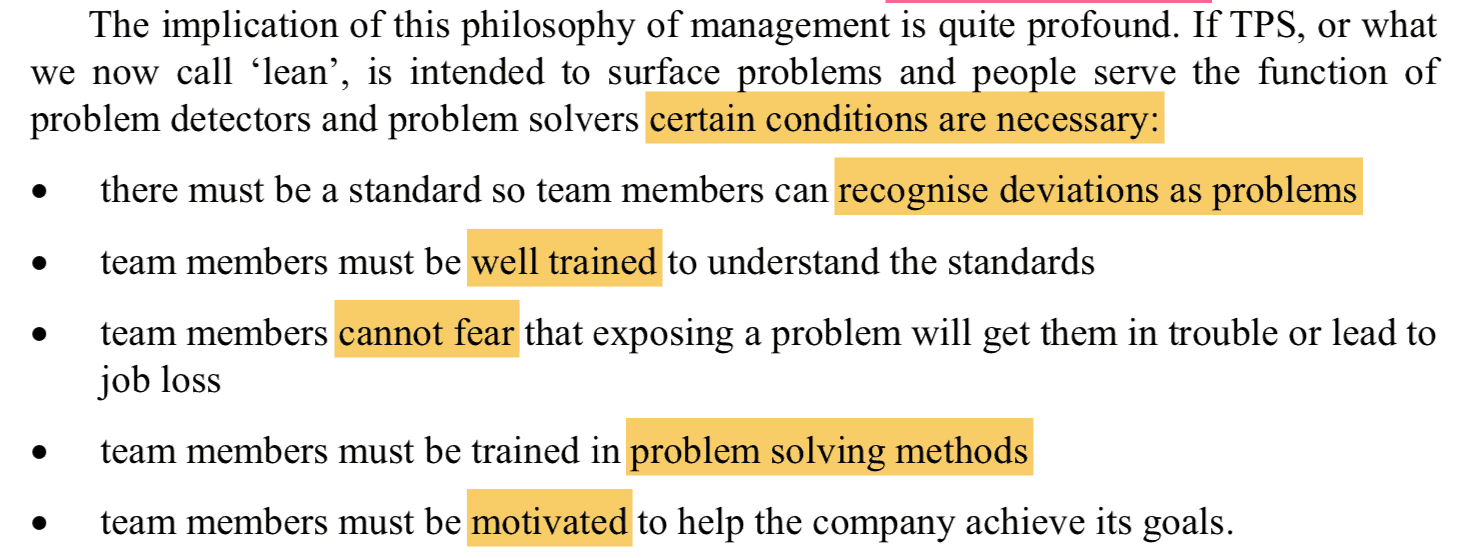

As the HRD name would suggest, that group plays a big role in developing the human resources of the company… not just because it's nice or respectful, but because it's good for Toyota:

Liker and Hoseus write about how many companies try to copy Lean tools or have a program with a handful of improvement experts. What really matters is the culture, as they explain:

A company having a “5S program” or a “Lean Six Sigma program” that doesn't address those cultural factors… why would they expect to get the results that Toyota gets?

Join me in Japan for the Lean Healthcare Accelerator Experience

See firsthand how Toyota and leading Japanese organizations develop their people as the foundation for operational excellence. On this immersive trip, we'll go beyond the tools to explore the mindsets, systems, and leadership behaviors that make “people development” a daily reality. You'll return with actionable ideas to build the same culture in your own organization. Learn More.

Please scroll down (or click) to post a comment. Connect with me on LinkedIn.

Let’s build a culture of continuous improvement and psychological safety—together. If you're a leader aiming for lasting change (not just more projects), I help organizations:

- Engage people at all levels in sustainable improvement

- Shift from fear of mistakes to learning from them

- Apply Lean thinking in practical, people-centered ways

Interested in coaching or a keynote talk? Let’s talk.

Join me for a Lean Healthcare Accelerator Trip to Japan! Learn More

In conventional business practice, tangible assets (such capital equipment) are those which will yield a future income. Employees are not capitalizable (nor depreciable), and so they are not understood by owners to be tangible assets. They, as well as Lean itself, are intangible assets. Furthermore, Lean must compete against other types of investment which have a much greater probability of yielding future incomes. Skillful manipulation of income-yielding tangible assets counts for far more than skillful development of human abilities. Unfortunately, people-development companies are seen as anomalies unworthy of emulation.

Here is the discussion on LinkedIn:

Including this comment from Joshua Sanchez:

People forget that Lean is a mindset, not a set of tools. In America, we look for who to blame rather than processes. Great article!

Blame isn’t just an American problem, sadly.

I saw this article from Singapore yesterday:

“18 staff disciplined after “human error” at TTSH put patients at risk of infection”

This sounds like it was an ongoing systemic problem for a period, yet the hospital’s reaction is to impose “warnings and imposed financial penalties against the 18 staff for the lapse.”

They call it “human error” but it sounds like “bad system” to me.

I had a chance to see an advance showing of an upcoming patient safety documentary. One medical expert said because all humans are prone to error, we need to design SYSTEMS that protect patients from error. They said “zero error” is impossible, but we can work toward “zero harm” by having robust systems. I don’t know if the Singapore hospital issue involved poor training, poor visual management, a lack of checklists, poor supervision or what… but those sound like system issues to me.

Studer uses the term “mandatory” for Must Do behaviors like hand hygiene and 5-rights despite the fact that systems can be improved to enable optimized compliance. And it’s incredibly effective. Personal Accountability is still a thing and isn’t entirely mitigated by checklists, training opportunities or technology enablers.

There’s not a healthcare professional in the civilized world that doesn’t know that poor hand hygiene leads to HAI’s. I’m not sure why we’d hesitate to hold staff accountable for opting out of patient safety.

Robert, what’s the connection to this post? Your comment seems like a non sequitor.

Various studies show hand hygiene compliance rates are about 33%. Doesn’t that scream “systemic problem” to you? What are you going to do, fire all of the non-compliant people? Being overburdened timewise, empty hand sanitizer dispensers… these are solvable problems and they go beyond “personal accountability.”

Knowing a bit about Studer (the man and his work), doesn’t “must do” mean “must figure out a way to make happen” instead of “must do or fired?”

Hmmm, just saw this and not sure if my original comment got posted to the wrong thread. But in terms of Studer’s take on “mandatory”, it’s at least as much (if not more) of the latter than it is the former.

From his recommended guidelines; “Have checks in place to validate non-negotiable behavior. Anyone who is not willing to comply should be allowed to leave the organization.”.

System improvement opportunities don’t absolve employees of individual accountability for performance (and particularly patient safety). You get 33% hand hygiene standards rates by tolerating non-compliance.

You’re using passive language… it’s not that “it got posted” to the wrong thread… you might have done so, Robert ;-)

I agree that if something is important (like hand hygiene), then there need to be checks in place. Leaders can’t just assume that things are happening the right way… and then blame frontline staff when the right things don’t happen.

The flip side of “tolerating non-compliance” is “not creating a system in which success is easy / possible.” If people are overworked (which is often the case), that’s a systemic problem, as are empty hand sanitizer dispensers, which I easily find all the time. It’s not just a matter of “personal accountability.” If you’re in a desert, can I hold you accountable for not drinking enough water?

Also this from Studer….. “Are there consequences for non-compliance, up to and including termination? I hate it when it comes to this, but we know that some staff members will not change their behavior unless you tell them the consequences and they know you mean it.”

Again, I think we have to look to see if employees “will not” or “cannot” follow hand hygiene practices.

Hah, it’s on me. It was in response to your previous comment. Not the original post

Totally agree with building system enablers, but accountability still matters. I was at gemba with a lean director at a large hospital. I noticed a piece of equipment staged in front of a hand-washing station. So I asked her about their hand hygiene initiative. Her quote (or pretty close to it) was, “we tried to do that a couple years ago, but it didn’t stick”.

They didn’t have a process problem. They had a people problem.

“It didn’t stick.” Why leap to blaming the front-line staff (if that’s what you mean by “people”)? That scenario sounds like a management problem. Management are people too.

What does “accountability” mean to you?

At far too many organizations (meaning most of them), the word means blaming workers for things that are out of their control.

How is hand hygiene beyond an employees control in almost any quasi-modern healthcare facility? Again, totally agree that we can enable that thru better design. But every patient exam room has a hand washing station. Virtually every unit I’ve ever seen has multiple hand sanitizing stations. There’s not a clinician in the modern world who can’t tell you the 5 points of hand hygiene. So it absolutely is more of a “will not comply” than can not comply” dynamic.

HAI’s kill people. Those rates can be virtually eliminated with proper hand hygiene. Heck, those rates can be virtually eliminated with proper hand hygiene using expired hand sanitizer. Hand hygiene isn’t put out anyone’s control. It’s a choice. And tolerated non-compliance kills people.

Accountability to me means being held personally responsible for required behaviors which are in my control

The debate then is how much is “under my control.” Are the nurses in your hospital expected to literally do 85 minutes of work each hour, as I’ve seen before? As long as that’s the case, I’m not going to judge people for skipping some required tasks when their job design makes it impossible to do everything properly.

Typically not a lot of correlation between patient volume and HAC rates. Pretty strong correlation between hand hygiene and HAC rates. The hospital with the highest HAI rate (they could cut their rate in half and still be worse than average) here in Australia isn’t in a high volume metro area. It’s in Townsville. Good hospitals practice good hygiene despite of how busy they may be.

Actual hand-washing isn’t required before/after a significant majority of nurse/patient interactions. Hand sanitizing is. Takes a few seconds. Saves lives. I’m pretty sure most, if not all , of the nurses on my Quality team will say the same thing. OR suites get busy too. Surgical teams should still be accountable for timeouts. Busy nurses should still be accountable for BBE (which takes no time at all).

Again, totally agree that there is a lot we can do on the process/management system side to enable higher compliance. But compliance to mandatory behaviors (especially hand hygiene and timeouts) is still a choice.

Yes, I realize hand sanitizing doesn’t take long. But, when the closest dispenser or two is empty, there’s a system problem. Now we’ve made the nurse’s work more difficult. “But I’m not going to touch the patient when I go in,” the nurse rationalizes. They often end up touching the patient anyway.

I’m not surprised that there isn’t a correlation between “patient volume” and HAC rates. Because American hospitals will often ruthlessly cut staff to match volume. They’re probably equally overworked as patient volume scales. Of course, a truly Lean organization isn’t understaffed… they allow for a bit of overstaffing to allow for better quality, improvement work, training, and just not being so damned stressed and pressed for time.

You keep pointing to individual “choice” but I think you had it right when you said “Good hospitals practice good hand hygiene” — that sounds like there are systemic factors at play.

If a hospital’s hand hygiene compliance rate is 33%, that’s not due to empty hand sanitizer dispensers. And “good hospitals” are more about leadership both embodying and enforcing mandatory behaviours. The only system factor involved in that is whether or not leadership tolerates behaviour that absolutely kills people.

Hand hygiene stats are pretty interesting when you break them down. Typically non-compliance isn’t evenly distributed. A significant majority of clinicians comply 100% of the time. A minority is typically responsible via high individual non-compliance rates. That usually holds true across an entire hospital as well as in specific wards. So the system is capable of delivering compliance. I’ve been in hospitals in close to 3rd world conditions that figured out ways to make hand hygiene work.

What would Toyota do if a handful of workers repeatedly were too busy to wear safety equipment (while others were) or risking the lives of the people around them?

Lean is not about “enforcing” — it’s about making it easy and default for people to do the right thing the right way.

I don’t buy the Toyota analogy. For one, they always have PPE available. Secondly, job design is good so workers have time. And, I’m convinced that if there WERE a shortage of PPE, then they’d stop the line and not let people work in an unsafe condition. If somebody is CHOOSING to not wear PPE, management would absolutely address that. It’s a CHOICE to wear safety glasses on your head.

It’s not a choice to be an overworked nurse in a hospital. Their only choice is to file complaints with a regulator or a union about short staffing and quality problems.

If the average rates are 33%, then a “significant majority” being at 100% would mean the overall numbers would be over 50%. Your proposed math doesn’t add up. If you have studies and data, please cite or share them. Otherwise, it seems like you’re making up numbers and blaming nurses, so please just stop.

In the hospital where you work, do you have an aggressive program to root out and fire nurses who are choosing to not perform hand hygiene 100% of the time? What are your hospital’s numbers?

And also, you keep making the case that it’s a systemic issue, not a “bad nurses” issue.

“I’ve been in hospitals in close to 3rd world conditions that figured out ways to make hand hygiene work.”

That must mean the HOSPITAL has a better system. It’s not that the hospital has better nurses who care more about “not killing people.”

Here is an an example of a hospital that built a “tollgate” that literally put a barrier across the door unless hand sanitizer was used. For a number of reasons, this didn’t last long. But it was said to be effective.

https://www.leanblog.org/2009/02/error-proofing-handwashing/

That helped with situations where busy staff forgot to do HH. We’re human. We forget. That’s not the same as intent.

Robert:

As a nurse of 25 years in Texas and connected with nurses in every state of the US, leadership doesn’t care about hand hygiene compliance (they say they do… but they don’t). They care about productivity, throughout, turnaround times.

You speak of 3rd world countries making hand hygiene work. My question is.. are those countries as money driven as the US? Is their goal quality care or exceeding budget and getting bonuses? The US hospitals (was he large majority) are money driven and truly do not care when the nurses speak of barriers they come up against to effective hand hygiene.

The hospitals with the highest HAI rates is the US have a couple things in common. None of them are among the top 25 busiest in the country and they each got dinged with a 3-5% reimbursement penalty from CMS. Busy is not a barrier to hand hygiene for the hospitals with the highest patient volumes. It’s not hard to make a reasonably compelling business case that hand hygiene makes as much financial sense as it does clinical sense. Driving efficiency isn’t mutually exclusive from optimizing patient safety. Some of the best ED’s in the US are also the busiest.

I’m not an apologist for bad leadership. But part of good leadership is holding people accountable for universally-accepted patient safety processes like hand hygiene and timeouts. Totally stipulated that things can always be done to enable those things more effectively. But also totally acknowledging that some people won’t do it anyhow.

Performance management is part of a management system. Accountability is part of a management system. If I walk into a busy production floor without safety glasses, odds are pretty high that someone will let me know within about 30 seconds. If I walked into a hospital ward and started touching stuff, a hospital with effective performance management will immediately call that out. Hospitals that tolerate non-compliance won’t.

And you keep using the “busy” justification. Again, not a lot of correlation between “busy” and hand hygiene compliance. Busy ED’s tend to be safe ED’s. High volume ED’s tend to have better outcomes and lower HAC rates. So lots of busy hospitals and clinicians have figured this out without automatic barriers, RFID monitors at hand washing stations, etc. They just don’t tolerate non-compliance. It really is that easy.

Robert

No where in my comment to I even mention “busy”. You missed the point. You shot back a response that was irrelevant to my comment.

Deena – I’ve been the one talking about nurses being busy if not overloaded with work. I think he was replying to me.