Actually being a patient in the emergency department is a learning experience, to say the least. I've done that twice in the past twelve months (two cases of really bad stomach flu with high fever). I don't recommend this if you can avoid it.

What I do recommend is an interactive learning experience called “Friday Night at the ER.“

I was invited to sit in as a guest for a daylong session as a guest of Kay Hall, who is a trained facilitator for this experience. I met Kay years ago and, knowing her Lean experience, I trusted her recommendation that FNER was working checking out.

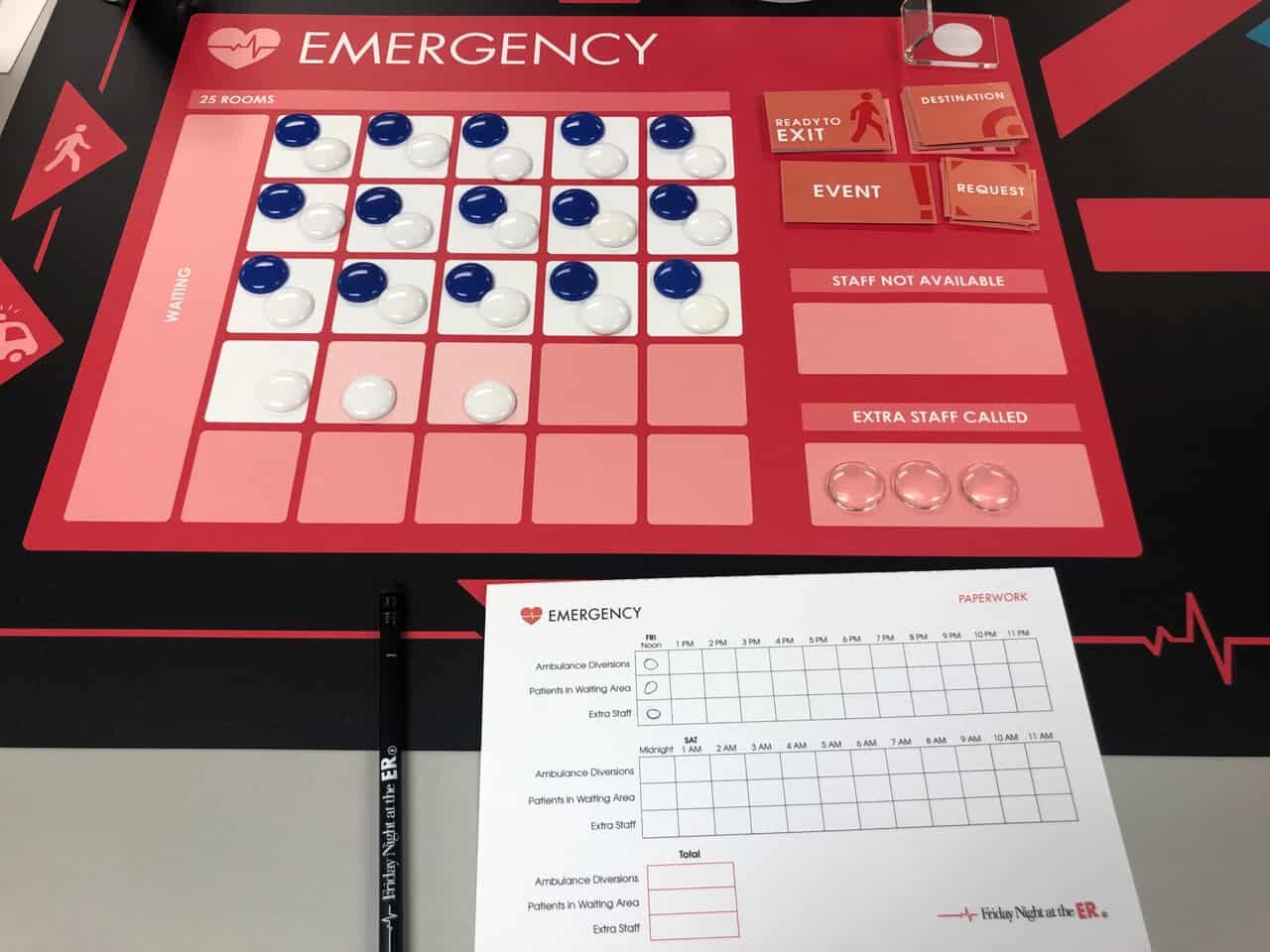

I'd call FNER a “tabletop simulation.” Picture a group of healthcare professionals and leaders around the table with a large hands-on simulation mat and pieces in front of you.

I was seated at a position around the board, ready to play, with this view of my part of the board:

There were others around the table, ready to run their own part of a hospital… surgery, ICU, and a stepdown unit. The four of us were going to work as a team to try to survive a simulated busy Friday night in the hospital. It's not just the emergency room we were simulating… it was multiple intertwined “value streams” of patient care, if you will. The game could be called “Friday Night at the Hospital.”

Here's one picture that shows part of the broader game and the flows between departments. Patients can enter through the ER or as direct admits to different units. Patients can flow out of departments into others, or they can be discharged to go home, of course.

Once we started playing, I got so into the game that I forgot to take more pictures (or I should say I was too busy).

I've long been a fan of learning exercises like this, since being exposed to the “MIT Beer Game” when in grad school there 20 years ago. You can play the beer game online, but there's something to be said for a tactile, group experience. It's better than sitting in front of a browser alone. The beer game teaches system dynamics principles in a fun, interactive way that you'll never forget.

For a few years, I've been certified to facilitate a group-based change management simulation experience (“ExperienceChange“) that's a hybrid… it's a computer-based interactive simulation, but it's done together with a group of people who are physically at the same table. You get the elements of group dynamics and having to work together on the team, with the teamwork and collaboration challenges that might come with it. You don't just learn and concepts in the game, games like this can be a great team-building exercise, as well.

FNER is a completely physical game. From their description, it teaches:

I think Lean connects to all of these concepts really well, or the game can be connected to Lean. But, it's not strictly designed to “teach Lean” and it can be used outside of organizations that practice Lean, of course.

One of the key decisions that you make throughout the game is about staffing levels. Each department has a capacity in terms of the number of beds. You can call in staff from home (which, as in the real world, isn't immediate) and you can send staff home early. At a bigger picture level, the group playing the game has to make strategic decisions about how to collaborate and whether or not we accept the backlog of waiting patients as being “normal” or if we decide to do something about it.

Similar to The Beer Game, there are cards that you flip for each hour that tell you how many patients are arriving and how many patients need to move to other departments. There are also some wild card events, such as a staff member getting sick and having to go home, etc.

The game is scored using what you might call a “balanced scorecard,” of sorts. It measures quality, cost, and efficiency. There are staffing costs and there are scores for quality (Being understaffed and causing delays hurts quality and safety). The E.R. being on diversion hurts quality (and costs you revenue).

The group I was playing with consisted of myself (an engineer with an MBA) and people with clinical backgrounds.

Without the constraints (or tyranny) of budgets or policies that would prevent us from doing the right thing, we decided our strategy was “putting patients first” — except we meant it (it wasn't just a slogan).

We decided that patients waiting was the worst thing that could happen. We made sure we were slightly overstaffed, the best we could. The cost of extra staff was not as bad as the cost of lost revenue and bad patient care. Again, our goal was zero patient delays.

Many hospitals (if not most) have a primary goal of keeping every caregiver and every resource busy. But, I thought healthcare was supposed to be different than manufacturing and other industries?

Playing the game also reminds me of the old Toyota idea (from Taiichi Ohno, I believe) that asks which you find more bothersome:

- Seeing idle resources (people, equipment, rooms) or

- Seeing patients not flowing

The waste of idle resources is usually much more visible than is the waste of poor flow. This leads many leaders then focusing on creating a system that keeps everybody busy. But is that really the goal of a business or a hospital?

Keeping resources 100% busy (or near to it) is really bad for flow, quality, and service, whether you're running a bank, an MRI, a call center, or a factory. I know this as an industrial engineer and my appreciation for “Factory Physics,” queuing theory, and “Little's Law.”

I've written about the dangers of 100% utilization before:

Through our strategy of being “slightly overstaffed,” our team was the winner from a financial perspective. We had higher labor costs, but also had higher revenue and fewer penalties for bad patient care.

Our team wondered, “Why isn't that the way every hospital is managed?”

In my experience, the game was highly engaging. Participatory learning is really the best way to go. Working through team dynamics is always interesting. We had agreement over our strategy. It would have created another challenge if our team had people who disagreed with the approach and philosophy.

In a game like this, the lessons about transparency and visibility are clear (and related to Lean concepts). Unlike a real hospital, we had the benefit of being literally seated around the table. This improved our ability to collaborate, make shared decisions, and to avoid suboptimizing our own silo.

Another important takeaway for a real hospital is figuring out how to create that level of visibility, transparency, and collaboration in real time, whether you can physically get people in the same room or not to manage your “value streams.”

I highly recommend this activity and this workshop. Let me know if you'd like me to help facilitate this within your organization, in partnership with the team that created Friday Night at the ER.

You can learn more about FNER through their website, and this articles:

Healthcare Change Agents — Interview with Bette Gardner, CEO and Founder, Breakthrough Learning

I will also be recording a podcast soon with Bette and Jeff Heil, their COO, so I look forward to bringing you that discussion about the company and their simulation.

Edit: Here is the podcast:

What do you think? Please scroll down (or click) to post a comment. Or please share the post with your thoughts on LinkedIn – and follow me or connect with me there.

Did you like this post? Make sure you don't miss a post or podcast — Subscribe to get notified about posts via email daily or weekly.

Check out my latest book, The Mistakes That Make Us: Cultivating a Culture of Learning and Innovation:

Sounds like an interesting simulation. I like the fact that it looks at the broader value stream beyond the ED. But it also sounds like it rewards potentially bad population health management. Patients don’t choose ED’s based on wait time (nor should they per this study https://www.uofmhealth.org/news/archive/201407/sickest-emergency-patients-survival-highest-busiest ). All patients are not equal and treating their wait times as a homogenous metric is dangerous. A plurality or majority of patients in the ED would be more effectively treated in a primary or critical care setting. Making the ED a more convenient option for lower acuity patients actually reduces access for high acuity patients. So unless the FNER sim measures triage effectiveness and door-to-doc time by acuity, it’s not necessarily reflective of real-world ED management. I would rather have the 80% (lower acuity patients) wait longer if I can get the 20% (high acuity patients) in faster, even if it meant my overall average would increase. That would also incentivize better pop health behavior as more low acuity patients would end up choosing a more appropriate level of care.

Still, cool sim.

The simulation isn’t meant to be 100% realistic. It’s a learning exercise.

I was largely responding to your quote;

“Our team wondered, “Why isn’t that the way every hospital is managed?””

There are very valid reasons why every hospital isn’t managed that way. Because you tend not to get better outcomes or higher revenue (especially if it’s even a moderately competitive healthcare market). You tend to get more patients using the ED in the place of primary or urgent care. And that’s bad for population health. It’s even worse for the reduced access for high acuity patients.

Improving efficiency within healthcare isn’t terribly complicated. Improving efficiency in healthcare without compromising the other legs of the Triple Aim IS spectacularly complex. There are far too many “good” lean healthcare initiatives that do the former but without any visibility to the latter. So until Lean practitioners spend less time reinforcing their traditional lean capabilities and more time learning the basics of healthcare (i.e what’s a DRG, how does a hospital actually get paid for what they do, what’s the difference between an NP and an RN, etc) Lean will continue to have an overall net negative impact on real patient outcomes.

But like I said, I think it’s a cool sim.

Maybe the next version of the Sim can include a station on the board for Primary Care and Insurance Availability since those are two aspects of the larger system that affect E.D. volumes.

I wish hospitals were managed in a way that had a slight amount of excess capacity (to the benefit of patient flow and care) instead of focusing on costs as a primary objective. I wonder if anybody has formally studied whether spending more on slight overcapacity leads to more revenue (and other measurable benefits) in a way that means the extra staff pay for themselves.