I started my career in manufacturing, so that's just one reason I'm interested in the topics of offshoring (sending manufacturing work overseas) and what's now called “reshoring,” or bringing jobs and factories back to the U.S.

Somebody at A.T. Kearney sent me a link to their recent report on reshoring, with the headline:

Reshoring in Reverse Again

US manufacturers are not exactly coming back in droves. In fact, the 2018 Reshoring Index shows that imports from traditional offshoring countries are at a record high.

When you learn to look at data and workplace metrics through the “Process Behavior Chart” methodology, you learn to be skeptical of text descriptions like “a record high.” Does “a record high” mean that the data point is statistically meaningful? Not always.

Highlighted in the report:

- The largest one-year increase in imports from Asia to the US, a staggering $55 billion dollars (up 8% from 2016), since the economic recovery in 2011.

Again, I'm not sure if an 8% increase is a “signal” in the data or if it's just part of the “noise” in the metric. Did it go down 8% the year before? How much does this number normally fluctuate? That context matters, otherwise we're just reacting to every up and down, which might lead to bad conclusions or decisions (as I write about in my book Measures of Success).

- The Reshoring Index has dropped 27 basis points since rising to a 5 year high in 2016

I'm also not sure if a 27 point drop is signal or noise. I asked the A.T. Kearney rep if they had more data to share and, thankfully, they did.

About the “Reshoring Index”:

To calculate the Index, At Kearney first looks at the import of manufactured goods from the 14 Asian countries that have traditionally been offshore trading partners: China, Taiwan, Malaysia, India, Vietnam, Thailand, Indonesia, Singapore, Philippines, Bangladesh, Pakistan, Hong Kong, Sri Lanka, and Cambodia. Next, we examine US domestic gross output of manufactured goods. Then, calculate the manufacturing import ratio (MIR), which is simply the quotient of dividing the first number by the second. The US Reshoring Index is the year-over-year change in the MIR, expressed in basis points. A positive number indicates net reshoring, which occurs if gross domestic output grew relatively faster than imports from the 14 offshore countries.

So, a drop in the number means LESS reshoring. Is this a meaningful trend, though?

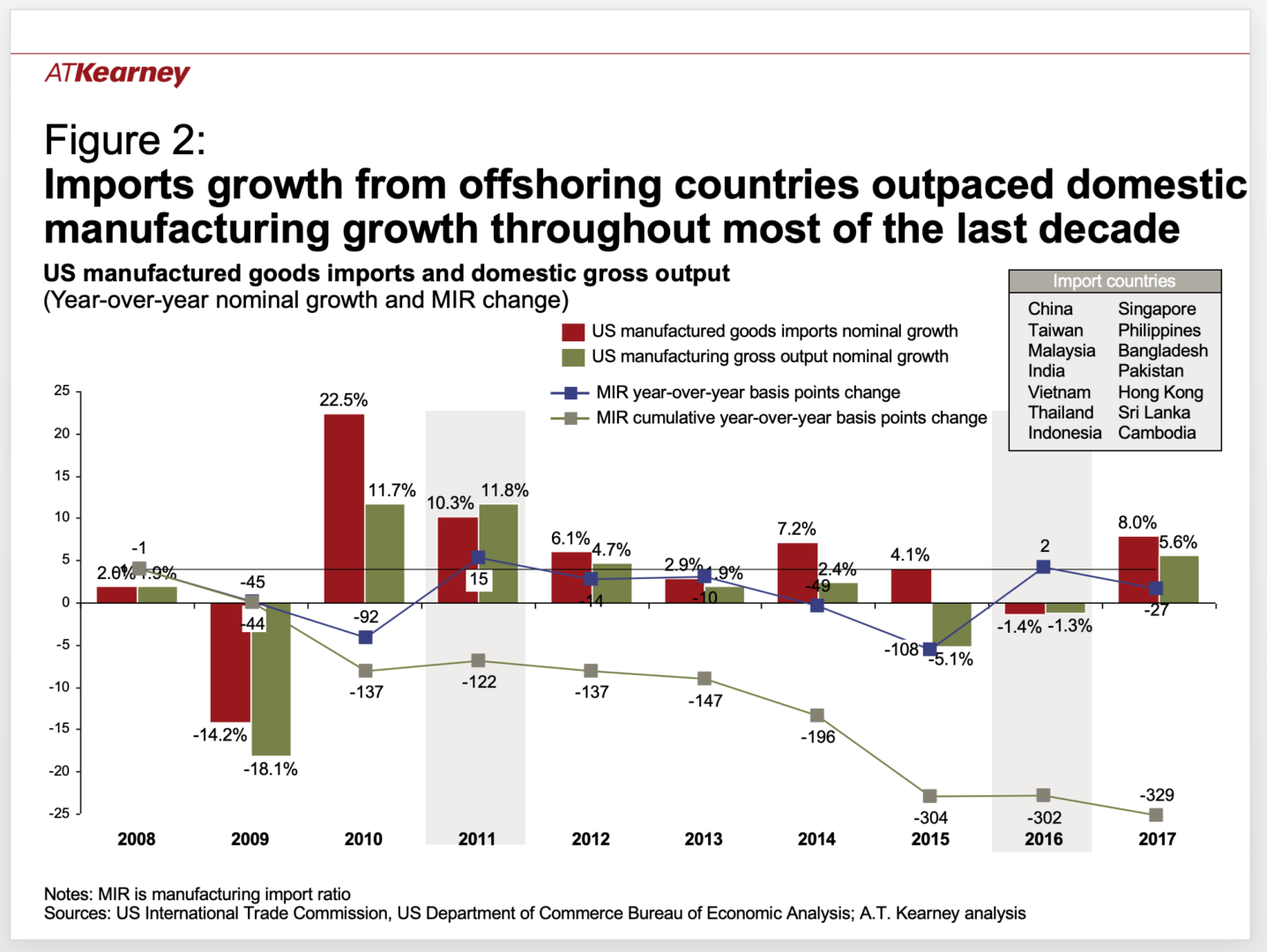

The chart from A.T. Kearney has a bit too much going on:

The blue dots and that line chart represent the reshoring index. Now, we can see better context. The number is up and down. I'm not sure the Y-axis is lined up properly, either. But, if I extract the data points, I can draw a Process Behavior Chart that is easier to digest.

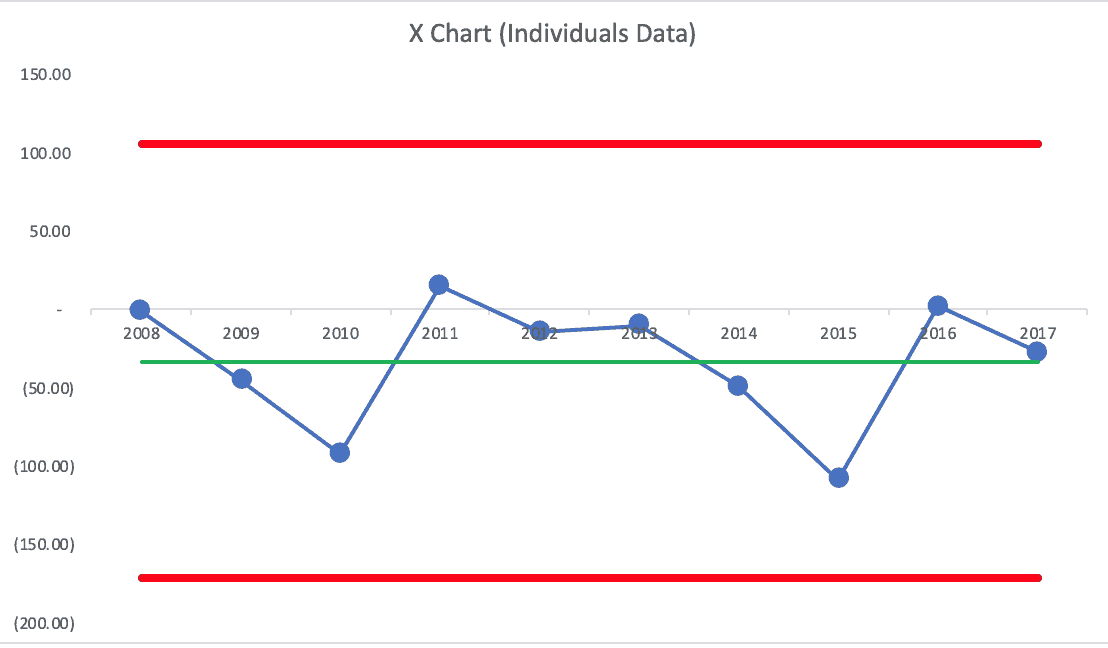

With the ten data points, from 2008 to 2017, I can calculate an average and the “Natural Process Behavior Limits” for the metric (see my spreadsheet). Here is the “X Chart”:

This chart tells us that the average “Reshoring Index” over those years was -32.9, meaning that there's still a net offshoring effect. The number was positive in 2011 and 2016, meaning there was net reshoring those years. But, was that ever a “trend” to begin with?

The Natural Process Behavior Limits are calculated based on the amount of “routine variation” in the system — how much does the number normally fluctuate from year to year? That's important context.

It appears to be what we'd call a “predictable system.” None of those data points is the result of a “special cause” that's worth investigating, explaining, or reacting to. The drop in the index for 2017 followed an increase in 2016. This number is fluctuating. There's no real need for headlines or press releases about it going up or down. Those changes aren't significant and the Process Behavior Chart shows us that.

Because it's a predictable system, we can predict that the 2018 number will fall between the Lower Limit of -171 and the Upper Limit of 105. The 2018 number is predictable unless something has changed significantly in the system (and I don't mean for this to veer into the political realm with talk of tariffs, etc.).

This Process Behavior Chart methodology isn't that complicated. It's really powerful. We can:

- Ask for additional data points if somebody makes a two-data point comparison

- Ask for additional data points if somebody says “this is the highest number in X years”

- Plot the dots (#PlotTheDots) and see what the voice of the process is telling you

- Stop overreacting to noise in the metric

I do think the A.T. Kearney report drew some accurate conclusions:

“The 2017 Reshoring Index shows that reshoring continues to be a drop in the bucket, and US manufacturers are not exactly coming back in droves.”

The overall negative index over the last ten years tells me that reshoring isn't really happening.

They also wrote:

“When we launched the Reshoring Index in 2014, much of the evidence for reshoring was anecdotal, often highlighting no more than a handful of high-profile cases, and the conclusions seemed to reflect wishful thinking or political agendas more than hard facts.”

We see this a lot in workplaces. Somebody has a PowerPoint slide that “proves” there is an improvement, but it's based on a comparison of two data points or a dubious linear trend line. Often, it's “wishful thinking” more so than an attempt at misleading anybody intentionally.

But, the Process Behavior Chart methodology is a way of looking at “hard facts” — putting data in context and hearing the real “voice of the process” instead of what we want to hear.

That's why I wrote Measures of Success: React Less, Lead Better, Improve More. I hope you'll check it out. I'll probably release the Kindle edition through the Amazon store next week. If you can't wait, you can buy and read today in PDF and other formats through Leanpub.com.

Please scroll down (or click) to post a comment. Connect with me on LinkedIn.

Let’s work together to build a culture of continuous improvement and psychological safety. If you're a leader looking to create lasting change—not just projects—I help organizations:

- Engage people at all levels in sustainable improvement

- Shift from fear of mistakes to learning from them

- Apply Lean thinking in practical, people-centered ways

Interested in coaching or a keynote talk? Let’s start a conversation.