For a long time, I've been an advocate for the parallels between Lean and an approach called “Just Culture.” See previous blog posts on this topic. Here's a good overview of Just Culture, which says, in part:

“A just culture recognizes that individual practitioners should not be held accountable for system failings over which they have no control. A just culture also recognizes that many individual or active errors represent predictable interactions between human operators and the system in which they work.

However, in contrast to a culture that touts no blame as its governing principle, a just culture does not tolerate conscious disregard of clear risks to patients or gross misconduct, such as falsifying a record, performing professional duties while intoxicated, etc.”

Leaders in a Lean culture also don't blame individuals for system failings “over which they have no control.”

Can CEOs, however, be held accountable for the culture in their organizations since they DO have control over their behaviors, the tone they set, and the example they set for others?

I can see parallels in situations where a CEO says they “endorse” or “support” something like Lean or Just Culture.

But, support isn't enough if there isn't action. Is the CEO leading by example? Is the CEO saying one thing and doing another?

You'll never make progress with Lean or Just Culture if the CEO says they support it, but then go blaming and firing individuals who are involved in systemic errors.

Neither Lean or Just Culture can take root in a culture of fear.

So, how are organizations doing on this front?

A recent blog post from Physician's Weekly explores this and I'd like to build upon it:

HOW ARE HOSPITALS DOING WITH “JUST CULTURE”?

The post cites a journal article (requires paid access):

“An Assessment of the Impact of Just Culture on Quality and Safety in US Hospitals“

457 hospitals (presumably American) were surveyed.

“In all, 211 of 270 respondents (79%) indicated that their hospital has adopted Just Culture.”

But what does “adopted” mean? When people ask me how many hospitals have “adopted” or “implemented” Lean, I can only answer, “I have no idea.” It's not binary. You might say you are “implementing” or “practicing” Lean. Adopting Just Culture and changing a culture isn't like flipping a light switch. It takes time. Is there really a consistent Just Culture in those 211 hospitals, or is it their goal or vision? Or is it wishful thinking?

“More than half believe that it has had a positive impact.”

They believe or they know? How would they know? By what measures?

Just Culture implementation and its degree of impact are associated with somewhat better peer review process, but not with objective measures of hospital performance.

So does that mean that Just Culture doesn't work? Or that organizations just haven't been practicing it diligently or long enough to see an impact yet? Do the hospital performance measures lag?

What about the process and culture that is supposed to lead to better results?

“Widespread adoption of Just Culture has not reduced reluctance to report or the culture of blame it targets.”

Well, there's a real Catch-22. If “widespread adoption” (again, what does “adoption” mean?) hasn't reduced the culture of fear or the culture of blame, then has it actually been adopted?

It sounds like it hasn't.

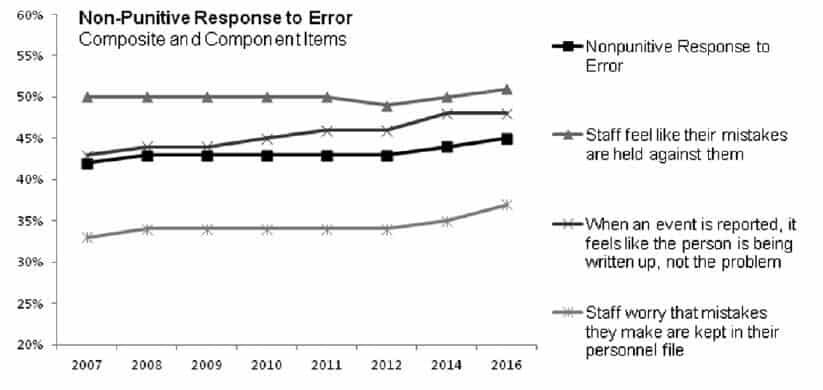

The Physician's Weekly post shared a chart from the journal article that shows progress (or a lack thereof) over the past decade.

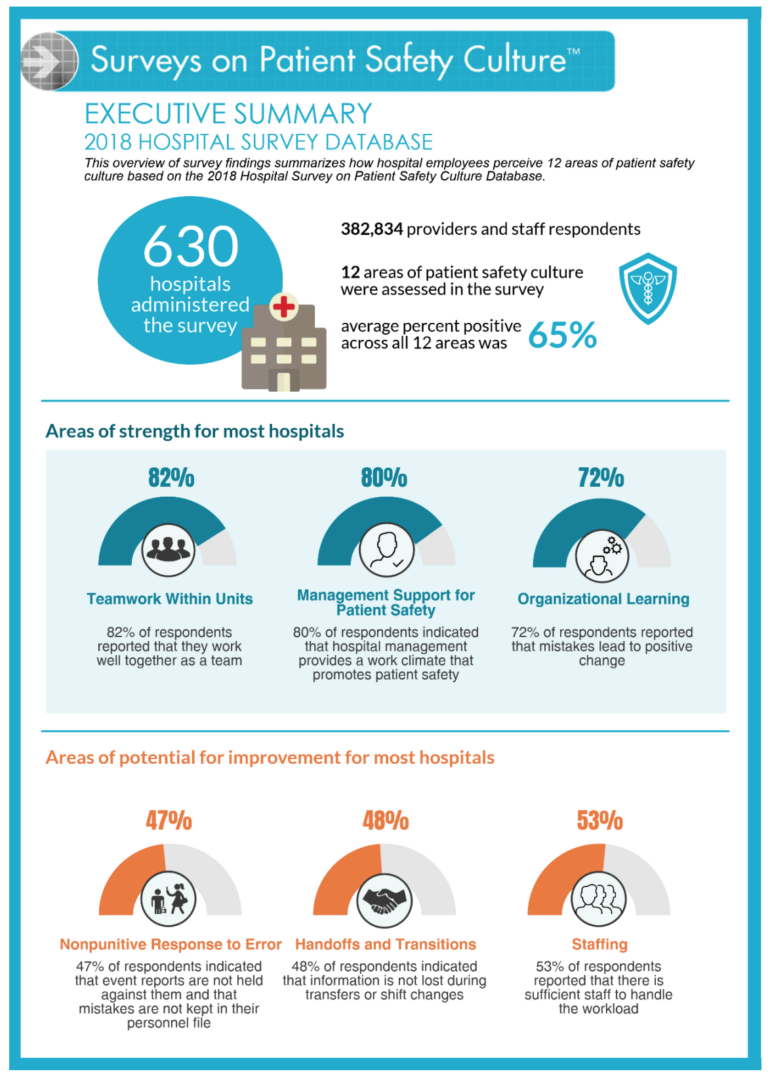

Here is the AHRQ survey data and information about it. Here is a link to 2018 results.

Using the methods of “process behavior charts” (see my book Measures of Success), it looks like there isn't much of a change in any of those process metrics.

Nonpunitive response to error: We'd want to see that going up. The first data point (about 42%) is lower than the last data point (about 44%), but it's hard to argue that's a significant change.

Staff feel like their mistakes are held against them: We'd want to see this measure going down and it's actually flat or it's just fluctuating around an average. So, no progress there.

When an event is reported, it feels like the person is being written up, not the problem: We'd want this to be going down and, if anything, it has increased slightly (but there's not enough data points to prove that there's a shift in performance there – looking for eight data points above an old average).

Staff worry that mistakes they make are kept in their personnel file: We'd want this to be going down… it appears not to be.

Well, that's discouraging.

It appears that the AHRQ survey looks across a broad set of hospitals, not just those adopting “Just Culture.”

So, the nonpunitive response to error rate is up just a bit to 47%? That still means HALF of healthcare professionals think there's a punitive response to errors.

The old habit of “naming, blaming, and shaming” is hard to break.

While Just Culture, like Lean, is sound theory… and the approaches work, in practice, when really embraced with the right style of leadership… that doesn't mean that everybody is going to adopt it. Or it means that some want to adopt it, but they're stuck or they don't know how to get there.

The use of “Lean tools” won't fix these cultural challenges. Heck, Lean tools might not even be effective in a blaming, punitive culture. How can we ask people to identify waste and quality/safety risks, if they have reasons to fear doing so?

That's one reason that I, and many others, have focused on the need for real executive engagement (not just support or lip service) and the need for culture change.

Here's an AHRQ webinar (more info) on Just Culture and patient safety:

How can we make more progress on these fronts?

Please scroll down (or click) to post a comment. Connect with me on LinkedIn.

Let’s work together to build a culture of continuous improvement and psychological safety. If you're a leader looking to create lasting change—not just projects—I help organizations:

- Engage people at all levels in sustainable improvement

- Shift from fear of mistakes to learning from them

- Apply Lean thinking in practical, people-centered ways

Interested in coaching or a keynote talk? Let’s start a conversation.

I know an organization where employees who are named in two or more risk management reports get called in by HR for disciplinary investigation.

It’s a system that’s supposed to ENCOURAGE people to report systemic risks. Somebody being involved (and named) in a systemic error doesn’t mean they did anything wrong.

I don’t know how the organization doesn’t see how getting HR involved wouldn’t discourage reporting… unless the actual goal of executives is to discourage troublesome reporting. But that’s certainly not a path to better safety.

It is quite clear that the vast majority of senior leaders are not interested in organizational transformation (or personal transformation) to things such as Lean or “Just Culture.” They seek to preserve traditions, including hierarchical power structures and associated behaviors, which leaders see as perks – benefits that one is entitled to – not as personal defects or organizational (system) failings. Your question, “How can we make more progress on these fronts?,” can only be answered by recognizing the totality leaders’ perspective (economic, social, political, and historical) and then devising new methods and means to influence them. Thus far, we have been trying to influence them from our perspective, which has proven to be largely ineffective. So that has to be recognized as a prerequisite to changes in the methods and means of influence.

I posted the comments below on a previous thread on creating an accountable and blame free environment —

Make sure your team get the praise for success and you carry the ‘can’ for any failures. Your team must have an accountable, but ‘blame free’ environment to operate in. This rule is one element in creating it. Let us not lose the plot here; we should all be concerned when there is a failure/mistake. Our goal is to make sure we learn any lessons that will be useful and ensure the mistake cannot recur. A Japanese proverb captures this thinking; ‘Fix the problem not the blame’. —

The best example of the power of the blame free environment I have seen was when I watched two of my daughters teaching our 12 month old granddaughter to walk. One daughter held her hands and the other stood in front of her with outstretched hands saying “Come on Samantha, clever girl.” Samantha took one step and collapsed into a heap on the floor. My daughters were all over her hugging her and saying, “Clever girl.” As a trained manager I tried to intervene and create some consequences for Samantha’s failure. The girls had to hold me back as I tried to beat the crap out of her with a piece of 4×4. My girls then repeated the procedure again with little improvement. What was interesting to observe as I sat tied to my chair, was that in the face of this complete failure the team’s morale remained very high. Within 30 minutes Samantha was staggering round the room going from chair to chair. Had my daughter allowed me to apply my professional management skills to the situation, I think Samantha would have crawled for the rest of her life. Make sure you don’t do this to your people and undermine their confidence. —

“It is a bad sign in any army/organisation when scapegoats are habitually sought out and brought to sacrifice for every conceivable mistake. It usually shows something wrong in the highest command. It completely inhibits the willingness of junior commanders to make decisions; for they will always try to get chapter and verse for everything they do, finishing up more often than not with a miserable piece of casuistry instead of the decision which would spell release.” Field Marshal Erwin Rommel.

A final thought on the helpful nature of problems and mistakes.

We must not see problems and mistakes as obstructions to our progress, but as a valuable source of instruction on how to proceed more effectively.

When dealing with patients we must apply source inspection principles to ensure that a mistaken action cannot produce a defective treatment for the patient.

Thanks, Sid. “Just Culture” isn’t completely “blame free.” It helps us separate systemic errors from certain intentional acts. In the case of some intentional acts, blame and punishment might be appropriate. But, it seems to fall in the ballpark of Dr. Deming’s estimate that said roughly 94% of problems are due to the system, not “bad apples.”

Most organizations err too much on the side of blaming individuals for systemic problems, which is “unjust.”

I would submit that this whole blog and comments be viewed from the perspective of CONTEXT and SUB CONTEXT.. That context being EFFECTIVENESS and EFFICIENCY. Now a very interesting might just emerge as to just what that has been posted is context and what is sub context…just saying