Episode #305 of the Lean Blog Interviews Podcast features a recorded talk by Mark Graban for a medical conference in Turkey. In this session, Mark explores the dual pillars of the Toyota Way–Respect for People and Continuous Improvement–and their vital role in healthcare organizations.

Respect for People means more than being nice. It includes ensuring staff have what they need to succeed, avoiding overburden, designing systems that prevent mistakes, and engaging people in meaningful improvement. Mark emphasizes that leaders must look at systems instead of blaming individuals, and create environments where people can thrive and learn.

The second pillar, Continuous Improvement (kaizen), is about engaging everyone, everywhere, every day. Mark shares practical stories and examples of how small, daily improvements–driven by frontline staff–can reduce frustration, improve quality, and strengthen patient safety. He also highlights the importance of leaders coaching, supporting, and celebrating improvements to sustain momentum.

Together, these two principles provide the cultural foundation for Lean in healthcare. Without respect, continuous improvement fizzles. Without improvement, respect remains empty words. This talk provides a clear, practical lens on why both are needed for lasting transformation.

I was recently asked to do a recorded video presentation for a medical conference in Turkey. I spoke about the dual pillars of “The Toyota Way“:

- Respect for People

- Continuous Improvement

The video is about 20 minutes, split about half and half on each of those interrelated topics. I'm coming to you from a hotel room, somewhat tired after a day of consulting.

Here is the video, with the slides and a transcript to follow. Soon, I might edit together the slides and the video.

Even if you don't have time to watch the video, please consider subscribing to my YouTube channel.

I'm also sharing the audio as Episode #305 of my podcast. Learn more about how to subscribe here.

For a link to this episode, refer people to www.leanblog.org/305.

Video:

Slides:

Here are the slides that I was talking from:

Transcript:

Mark Graban: Hi, my name is Mark Graban. I am the author of the book Lean Hospitals, and I'm a co-author of the books Healthcare Kaizen and The Executive Guide to Healthcare Kaizen.

It's my honor and privilege to be presenting to you today, via this recorded video, and I'm looking forward to the live question and answer session that will follow.

Today I want to talk about some of the foundational and important ideas about Lean… how it applies in healthcare, or in any setting.

We can define Lean in a number of ways. The Lean Enterprise Institute defines Lean as a set of concepts, principles, and tools. It's a way of thinking that's used to create and deliver the most value from the customer's perspective. In healthcare, we would generally refer to the patient.

The customer's perspective defines value. “We want to deliver the most value,” as LEI says, “while consuming the fewest resources, and by engaging people in continuous problem solving.”

Dr. John Toussaint, who was the CEO at ThedaCare, a health system in Wisconsin, one of the early innovators of Lean in healthcare, says that Lean is built on three bedrock concepts.

- One, respect for people.

- Two, scientific method to seek perfection.

- Three, a clear purpose to align systems, strategy, and performance to yield customer value as a result.

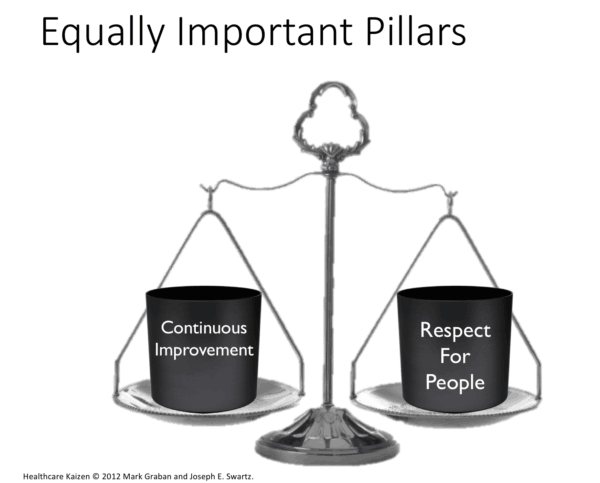

If we look back to, arguably, the origins of Lean, we look at the Toyota Production System, or what Toyota would call the Toyota Way. When you visit a Toyota facility, their visitor center is likely to have signs and banners proclaiming that the Toyota Way is both continuous improvement and respect for people. Toyota publications have referred to these as “equally important pillars.”

Before we think about Lean tools and other methods, it's important to step back and ask if our workplace environment in healthcare is a respectful environment. Is it respectful of everybody who participates in that system?

Respect for People

Arguably, the Lean approach to improvement and management should and must respect and support staff. This includes ensuring people have what they need to do their work, not putting people in the middle of a broken process.

A Lean environment doesn't drive cost-cutting through layoffs. We don't overburden people. We make sure we have the proper staffing levels. We give help and support when needed. We allow people to do meaningful work.

Respect for people also means not blaming people when they commit errors or mistakes that are caused by the system.

Respect means listening and engaging people in improvement because Toyota or any successful Lean healthcare organization would remind us that Lean and the Toyota Production System is not just about tools and methods. It's about how we manage. It's about an organizational culture that's built upon a philosophy.

Toyota describes this as an integrated system. We might see problems if we try to copy one part of an integrated system.

Toyota leaders today, not just in the past, in history, would describe the Toyota Production System philosophy as having four parts. First is putting the customer first. In healthcare, we would say putting the patient first.

Providing customers with what they want, when they want, in the amount they want it. In healthcare, we might not want care. We might need care, but I think that the general idea is the same — placing the patient first, and making sure that they get the care that they need or want when they need it, where they need it, and with the right quality level.

The second point of the Lean or Toyota philosophy is that people are the most valuable resource. That we must deeply respect them, engage them, and develop people in the course of our improvement work.

The goal of improvement is not just to improve performance, to improve metrics. Toyota would often say that the primary goal of improvement activity, or kaizen, is to develop people first and to help meet our goals second.

This third part of the philosophy is, again, continuous improvement, or kaizen. Engaging everyone, each, in every day.

The fourth part of that philosophy is having a focus on the place where the work is done, or the Japanese word for this is the “gemba.” If there's a situation where we have to do some problem solving, we should go to where the work is done and work with people to solve problems.

As Toyota leaders would say:

“Go and see, ask why, and show respect.”

Let's not try to guess about causes to problems or guess what solutions would be in an office or in a conference room. We want to go and engage the people who are in the middle of doing the work.

I want to share some other thoughts about what is meant by respect. Toyota describes their system as the Toyota Production System. Earlier names for their approach and methodology included things like the “Respect for Humanity System.”

It's very telling that they call it this, the Respect for Humanity System. Unfortunately, sometimes in healthcare settings, we see patients who aren't being treated with respect. We see nurses or hospital staff who might not be treated with respect.

Respect, it's not just a matter of being nice. Showing respect sometimes means that we challenge people. We challenge them to do better because we believe in them. We set challenging goals, but then, as leaders, we provide support to help them achieve those goals.

Respect for people means respecting each individual and their own contribution to the organization regardless of their level of education or their job title. Respect means that leaders help people improve, but we don't improve for them. We don't throw ideas at them. Instead, we coach.

It's sometimes said in this approach, when we're trying to help people solve problems we don't want to rob them of the ability to learn and improve on their own. When we give people answers we're stealing a development opportunity from them.

Respect for people. As Toyota originally called it, Respect for Humanity. That also connects to the idea of our human nature and showing respect for that. Recognizing our humanity, and realizing that we're all imperfect and prone to error, which is why we use the Lean method of error proofing or mistake proofing.

We don't just ask people to be careful. We don't ask them to be perfect. We realize that's not possible, so we want to make sure we design a process that ensures quality and safety — designing a process.

Designing that process is really the role of leaders. Leaders have an obligation to create an environment in which people can be successful. Respect means not blaming people when systemic errors or problems occur.

I recently worked with a doctor who had a patient come into a walk-in primary care clinic. There were a number of things that they did to help diagnose and treat the patient, but it was a Saturday. Staffing levels were low.

The doctor admitted and realized after the fact that he forgot to give an aspirin to the patient, which would be considered part of their medical protocol. Instead of blaming himself or the organization blaming him, I give this doctor a lot of credit that he thought about how to create checklists and protocols that could be used in the future to prevent a similar error like that from occurring.

Respect for people means when something goes wrong that we look at systems and processes in error proofing, instead of just blaming or punishing somebody for making an honest mistake.

Respect means not blaming people. It means not asking them to do too much, to do more work than can possibly done in a time frame, because overburden or asking people to rush will inevitably lead to errors and possibly harm to patients.

Respect means, again, not being easy on people. It doesn't mean making excuses for people, but it means recognizing our human nature and working together with them to help them succeed.

Part of that success is the idea that, because we respect people, we work to actively engage everybody in the organization in improvement. That is the second half of my talk here, about kaizen, or continuous improvement.

Kaizen – Continuous Improvement

Now I'd like to talk about kaizen. Kaizen is a Japanese word. It has two characters, kai and zen, it basically translates in reverse, where zen can mean good and kai means change.

The context of kaizen generally means continuous improvement, something that is practiced on an ongoing basis. It's part of the culture.

We've talked about the idea of creating a culture of continuous improvement as a goal. This is a goal that many organizations have, but unfortunately a lot of times people don't know how to make this a reality.

They might have a mission statement that says, “We aim to engage everybody in continuous improvement.” We desire to have a culture of continuous improvement, but how do we make that happen?

I've been fortunate to work with organizations in many countries, helping them get started in creating that culture of continuous improvement. That means engaging people in improvement.

It means talking to them on a daily basis, asking them to point out problems or opportunities for improvement, and asking them what their ideas are. Again, instead of just giving them answers, we want to be respectful in the way we engage people in improvement.

One of the early books about kaizen was written by Masaaki Imai, a Japanese man who studied Toyota and learned from Taiichi Ohno and other leaders from Toyota. He defines kaizen as the idea and the practice of everybody improving everywhere in every day.

This means many, many small improvements. It doesn't mean everybody does a large project every week, but it means we incorporate the ongoing improvement activities into our daily work.

Imai talks about four goals of kaizen. I've seen this work and apply in many healthcare settings. That we focus on this order.

First off, making things easier, making our work easier, which is different than asking people to work harder. When we help people eliminate waste and eliminate barriers to improvement they can accomplish more.

They can be less frustrated. They can be less tired, which leads to fewer employee injuries and reduces risk of error greatly.

We focus on making work easier, not because we're lazy, but because we want to use the limited time that we have in a given day to adding value. We want to dedicate that time to patient care instead of searching for equipment, searching for medication, searching for people, searching for the patient, even. We want to make work easier.

We want to make things work better. We want to improve quality. We want to improve the outcomes of our work. I've found people in healthcare are very excited to engage in that challenge.

We'd like to make things work faster, so we think easier, better, faster, but making things work faster, again, doesn't mean that we want people to do their work more quickly. It means that we eliminate delays. We eliminate interruptions, which allows us to complete the work more quickly and with more care, more caution, better quality.

The fourth priority is the idea of making things cheaper, reducing costs, without hurting quality.

To summarize, those four goals are easier, better, faster, cheaper, in that order. When we've seen organizations embrace this style of improvement, it's really powerful.

The co-author of my Healthcare Kaizen book, Joe Swartz, has been their director of improvement at a hospital in Indianapolis called Franciscan Health. They've been working the last 10 years to create a culture of continuous improvement.

They've implemented 25,000 or 30,000 improvements. They save a couple million dollars a year.

More importantly, that level of staff engagement, working towards getting everybody involved in improvement increases staff engagement and satisfaction, which helps increase patient satisfaction. It improves safety, quality, and other factors that are important in the hospital.

I've posted videos on my blog and YouTube with nurses, pharmacists, staff, and leaders from Franciscan talking about why kaizen is powerful to them. In one video the nurses say that the culture there at the Franciscan Health System is having staff input into everything.

They, meaning management, want staff figuring out how to fix things. What can we do to make our job easier? This is really important. “They,” again, management, “allow us to implement things to see if it will work.”

Everything involved with kaizen is built around cycles of improvement, cycles of learning. You can call PDCA, plan, do, check, act, or PDSA, plan, do, study, adjust. It's an iterative, incremental improvement cycle.

Kaizen can be applied to the hundreds, if not thousands, of small problems that we would face in our organization. Kaizen might also be described as an event — something that takes anywhere from two to five days. A small project where we bring people together to work on improvement — or it might have large strategic kaizen that are driven by executives and senior leaders.

Whether it's large kaizen, medium kaizen, or small kaizen, it should all represent PDSA cycles. When we are implementing a small change in a department, it might be easy to quickly test an idea, study the effect, make adjustments if needed.

A large kaizen, such as building a new hospital, doesn't allow for cycles of iterations, so that's why Lean healthcare, Lean hospital design now usually includes the idea of building prototypes or mockups that allow people to test the design, iterate, and improve it before it gets completely built.

The idea of kaizen has been something that healthcare leaders have advocated for – for almost three decades now. In 1989 Dr. Don Berwick, who's quite well known for his work with the Institute for Healthcare Improvement, published an article in “The New England Journal of Medicine” titled “Continuous Improvement as an Ideal in Health Care.”

He described kaizen as the continuous search for opportunities for all process to get better. That leaders can't just observe problems. They need to work with people to improve the way the work is done.

Some hospitals borrowed the idea from Toyota that says, essentially, we all have two jobs — to do work and to improve the way the work is done. Improvement work is not limited to specialists. It's something that we want to engage everybody in.

That process for doing so is pretty simple. We work as leaders to engage staff in finding problems or opportunities for improvement, and then we discuss them within the team. Maybe we have to discuss them with another department. It depends on the situation.

We find and then discuss the ideas or opportunities, and then we implement or test the idea. We might have to iterate and go back and try something else, but then once we've found something that is, indeed, an improvement, we then document and share the idea. We find, discuss, implement, document, and share.

What can we do as leaders? The culture of continuous improvement is really quite dependent on the behaviors of managers and leaders.

One thing that we can do is ask for kaizen. We can ask people to speak up and create an environment where it's safe to do so. To point out problems, to speak up about ideas, but then we also need to help create time for people to work on improvement.

We can't just ask them to speak up and have the ideas sit in a suggestion box, or on a board, or in software. We need to work with them to turn those ideas into action.

Another thing we can do is to lead by example. If leaders want a culture of continuous improvement, they can participate. They can get involved by implementing kaizen improvements about their own work.

They can coach, mentor, and lead others, which means going to the gemba, as I mentioned earlier. Going out into the workplace. Coaching people through cycles of PDSA, we can help teach and coach people around root cause problem solving when that's necessary.

Probably the most important thing, to continue the momentum of these improvement efforts is to recognize people and to celebrate kaizen activity. Again, when we find opportunities, discuss them, implement them.

We don't stop there. We document and share what was done for a number of reasons. One is to give recognition to the people who've put their passion, creativity, and effort into kaizen. We want to make them feel good about what they've done, which encourages them to participate in more improvement.

Then, as we share the kaizen improvements, we're spreading good ideas. We're inspiring others. We're magnifying the impact of the ideas that those people have.

To summarize, kaizen sounds simple. It's deceptively simple. We can engage people in improvement, but maintaining that requires a lot of energy, a lot of persistence, and a lot of dedication on the part of managers.

My hope for you is that if you don't already have this culture of continuous improvement in your organization, to step back and think not only about Lean tools, Lean projects, and Lean methods, but to think about this culture and this philosophy.

How do we demonstrate respect to our people every day? Part of the way we do that is engaging them in continuous improvement.

With that, I want to thank you for the opportunity that you've given me to share some thoughts and remarks with you today.

Please scroll down (or click) to post a comment. Connect with me on LinkedIn.

Let’s build a culture of continuous improvement and psychological safety—together. If you're a leader aiming for lasting change (not just more projects), I help organizations:

- Engage people at all levels in sustainable improvement

- Shift from fear of mistakes to learning from them

- Apply Lean thinking in practical, people-centered ways

Interested in coaching or a keynote talk? Let’s talk.

Join me for a Lean Healthcare Accelerator Trip to Japan! Learn More