tl;dr summary: In this post, I recount my experiences as an Industrial Engineer at GM's Livonia Engine Plant in 1996. The post discusses the harmful management practices of prioritizing quantity over quality and blaming workers for quality issues. This approach led to a downward spiral in quality, as illustrated through real memos and personal observations from my time at the plant.

My first job out of college was as an Industrial Engineer at the General Motors Livonia Engine Plant. Blogging didn't exist then (I didn't even have email or internet access at work), or I might have started my writing career then. Oh, the stories. I've shared some of them on this blog over time.

I've blogged about papers from the Don Ephlin files, a former UAW national leader. I have my own small collection of documents and artifacts from my days at GM that I thought I should keep in a folder. I still have that folder today.

A few of these memos tell the story of a quality and productivity death spiral that eventually led to our plant manager being replaced. And, by “replaced,” I don't mean fired or given an early retirement. He was, at least in title, PROMOTED to a role at GM Powertrain headquarters.

Thankfully, the new plant manager, Larry Spiegel, was one of the original “NUMMI commandos,” and he made a huge difference to the plant and to me, personally.

The Old Plant Manager, The Old Style

Under my first plant manager, Jack, there wasn't a “culture of quality.” There certainly wasn't a “culture of continuous improvement.”

Unlike Larry, Jack didn't really “go to the gemba” as a Lean leader does. If he did leave the office area, it was because some machine had broken down and had been down for a long time. So, he'd go out and stand and stare and glare and cross his arms. That wasn't really constructive or helpful. He certainly wasn't leading root cause analysis discussions. He was saying, basically, “Come on, hurry hurry, time is money.” He wasn't being a servant leader.

He was the type of imperial, autocratic “king-leader” that's supposedly now gone at current-day GM, as I've blogged about before.

It's one choice about how to lead, that top-down command-and-control style. At least GM wasn't pretending that this old style of leadership was somehow “Lean.” It wasn't “Fake Lean” or “L.A.M.E.” – it wasn't Lean at all.

We couldn't even SAY the word Lean or anything about Toyota in that environment. GM had a phrase they used – “Competitive Manufacturing.”

We did have some internal consultants hired by GM Powertrain headquarters. The consultants sent to use came from other auto suppliers who were ostensibly there to help… but the plant manager and other leaders didn't want their help. That's another story.

Our plant leaders at the time had the old habit of blaming the UAW workers for everything. I guess sometimes they would blame the engineers or low-level managers. They weren't buying into the W. Edwards Deming approach (Deming had passed away two years earlier and any attempts to embrace Deming methods in that plant died with him, apparently… something I blogged about for The Deming Institute.

Quality is Job 1? Or Quantity?

Ford had an old ad slogan in 1980s that said “Quality is Job 1.” I don't think Dr. Deming would have cared for that slogan, even though he taught Ford that quality should come first. Forget slogans – what matters is the way executives and managers behave – does that create a quality culture or not? We can ask that question in healthcare today… is patient safety job 1? Is patient safety really “always a top priority?“

At GM, the slogan was more like “Quantity is Job 1.”

The message from management, the metrics… most everything was focused on making the daily production numbers. Don't let inventory levels drop too low. Don't you dare shut down the Cadillac or Oldsmobile plants that were our customers. It was all about Quantity. Quantity, quantity, quantity.

There was, of course, a Quality Department. But, as Deming said, quality doesn't come from a quality department. At times, the people in Quality were more likely viewed as the enemy of quantity. They were those annoying nerds who slowed production.

Battles Between Workers and Management Over Quality

I worked as an Industrial Engineer supporting some machining lines (including engine blocks). The hourly workers (and the Quality Department) would get into battles with production supervisors and plant leadership.

The block machining line had a quality plan that stated, as I recall, that a part should be taken off the part roughly every 30 minutes for quality checks. I think they stopped the line, pulled a part down using a hoist, and checked key dimensions using gauges.

The UAW workers would often complain that management told them to skip the quality checks and to keep the line running when inventory levels were low.

I often heard management complain that the quality specifications set by Quality and Product Development were silly and unrealistic. Manufacturing didn't respect the specs, so they rationalized and made excuses for not following the quality plan.

I don't remember situations where a UAW worker was skipping quality checks because they were lazy or didn't want to work. They cared about quality. They had (or wanted to have) pride in their work, as Deming talked about. But, they got beaten down by what Dr. Deming called “the forces of destruction.“

I also have very vivid memories of an argument between a production worker (backed by the process engineer) and management about stopping the machines to do the planned tool changes. Doing so was, of course, part of the quality plan.

It was time to do the planned tool change, but management would say, “Keep the line running.”

Sure enough, because the tooling wasn't changed at the planned interval, it failed catastrophically not long after. This, ironically, created far more downtime and a longer, slower repair than a standard tool change would have taken.

Not focusing on Quality sure hurt the quest for Quantity.

The Downward Spiral Begins, April 1996

I'll embed snippets of the first two memos as images to tell the story and comment, but you can download them both as a PDF file here.

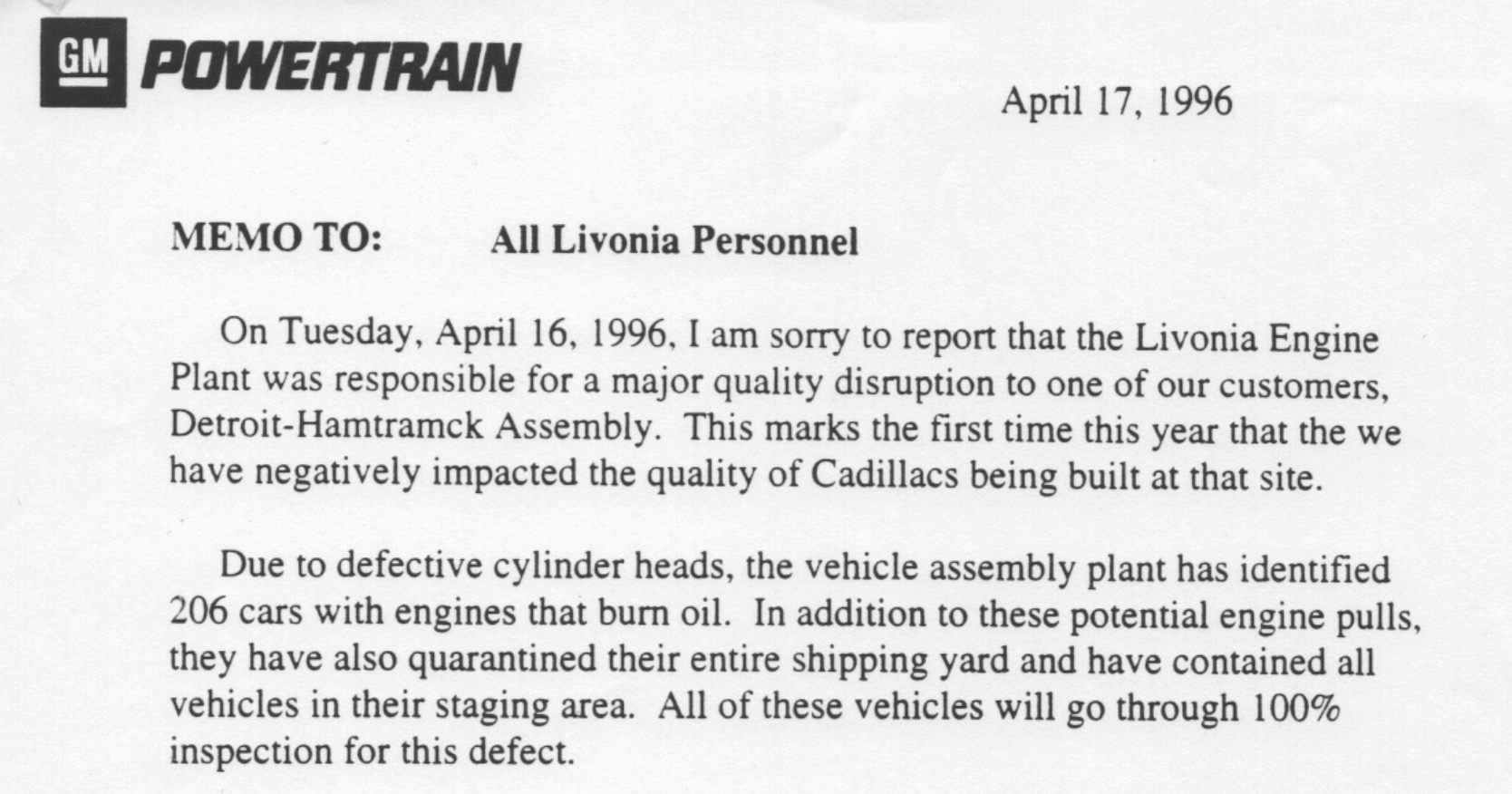

The first memo to all employees went out on April 17, 1996.

It was sent by Bob, the #2 leader in the plant, with the formal title of “plant superintendent.”

Long story short, some defective engines got to the Cadillac plant that burned oil. That's bad.

The Cadillac plant first started the car at the very end of the line when they were ready to drive it off. This served as the first functional “hot test” of the assembled engine that had been built at my plant, some 20 miles away.

Somebody in GM had gotten the idea we were supposed to “build in quality” (which sounds like a Deming or Lean principle), so our relatively new assembly line didn't include the old practice of hot testing the engines at the end of the line.

Because we didn't have a culture of quality and didn't have rock-solid processes, that created risk (even Toyota conducts “final inspection” at the end of automotive assembly).

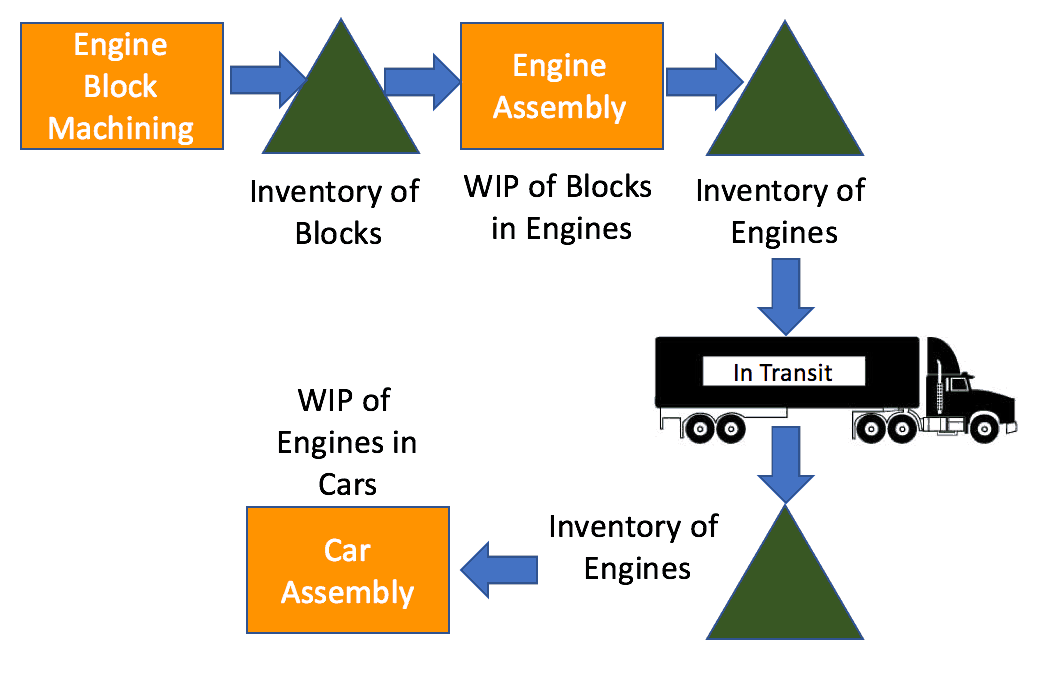

The risk: Every engine that had been put into a Cadillac on the final assembly line, every completed engine in inventory between our assembly line and theirs was potentially a bad engine… and more.

See this diagram with all the places defective engines could be in the flow / value stream.

The memo that was sent out after the smoking engines were found began like this:

To their credit, GM was good at taking measures to “contain” or “quarantine” a quality “spill” like this. They didn't hide, cover up or deny that there was a problem. Unlike healthcare, it wasn't possible to hide or cover up the problem, actually.

Doing a good “containment” is a necessary first step when you have defects being created (and healthcare sometimes needs to do a better job of this — protect the customer THEN do root cause analysis). Containment often means extra inspection and sorting. If you made bad parts (which is bad), sending them to the customer is worse.

The memo emphasized not only that quality problems are bad, but constraining production is bad. Well, duh. There's that “quantity first” mindset popping up. Of course, a factory has to ship products to make money. You have to ship GOOD products.

Ironically, taking steps to put quantity before quality in the short term causes problems with production quantity over time.

Here comes a bunch of empty words about quality. Believing quality standards are high and doing what it takes every day to ensure quality aren't the same.

Here's the juicy irony… remember, I said that management didn't let the workers follow the quality plans. So, after a big quality spill, management does what? They blamed the workers for not following the plan! You can't make this stuff up.

I saw many times when management didn't prioritize personal safety, either. These are all empty words.

A direct parallel to a hospital today would be a scenario where:

- Management and the quality group say that surgical teams MUST do pre-surgical time out and the “universal protocol”

- Management then pressures surgeons to skip those timeouts because they want more procedures taking place

- The surgeons shrug their shoulders (maybe they didn't want to do them anyway)

- Something really bad happens (wrong side surgery)

- Hospital executives send an angry memo reminding everyone to do timeouts!

The memo ends with more empty words:

GM and the plant's management shouldn't have needed an incident like that to teach them what to do regarding quality.

Of course “quality is not automatic.” We all know that. Management wasn't letting people do what was necessary for quality.

“We must all do our part” is like the phrase that Deming pooh-poohed: “Quality is everybody's responsibility.” Sure, everyone has a part to play, but quality starts at the top. The tone is set by senior leaders. I saw management directly interfering with good quality practices.

The results and this catastrophe were predictable. It was a matter of time.

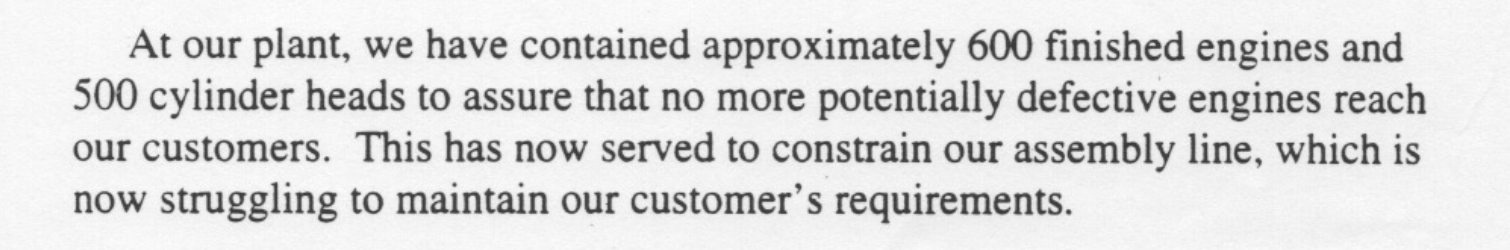

Memo #2: Quality Chimes In

Just three days later, on April 20th, a leader in the quality group wrote a memo written TO the plant superintendent but was circulated to all. I think it was a passive-aggressive way of making a point:

It began:

Plant management never said in writing, of course, that employees should use out of spec parts or not follow the plan. But pressure to do so was there.

The memo about following the plan… that was probably more about “CYA” than anything.

Looking at the first sentence of this next section, I'm not sure what “doing what we're supposed to do for quality” means spring cleaning, unless the quality manager was suggested we clean out upper management.

We had production workers and engineers wanting to “get with it” before but to no avail.

By “resources,” did he mean plant executives? Maybe not. He should have.

The memo says the plant manager signed an agreement saying we would hold to specifications. We should have had a copy of that agreement out on the shop floor to show the plant manager when people were being told to violate the quality plan.

Quality continues to remind management about how the quality processes are supposed to work:

Specs and what was acceptable to ship wasn't supposed to be determined by “equipment or employees [having] problems,” and that includes management having problems. Low inventory and the risk of shutting down the Cadillac plan wasn't supposed to mean quality standards could slip.

There was supposed to be, I guess, a “check and balance” between the “quantity first” management crowd and those who cared about quality. But, the balance was out of whack. Management got to decide “keep it running,” even if quality protested.

Of course, our plant's management wouldn't want our suppliers (other parts of GM or outside companies) to cut corners on quality. But they would do that if quantity was jeopardized.

The last paragraph sounds like a cry for help from a quality department that wasn't being acknowledged or respected:

And it ends with a quote:

I often felt like respect for our senior leaders wasn't owed… and it wasn't being earned through their disrespect for quality and the customer.

What Happened Next?

So, what do you think happened after this quality problem and the resulting memos?

I'll share more of the story in a future post:

How does this compare to today's hospitals and how they respond to a major patient safety incident? How should hospitals and health systems respond? What parallels could we draw? What lessons could we learn?

What do you think? Please scroll down (or click) to post a comment. Or please share the post with your thoughts on LinkedIn – and follow me or connect with me there.

Did you like this post? Make sure you don't miss a post or podcast — Subscribe to get notified about posts via email daily or weekly.

Check out my latest book, The Mistakes That Make Us: Cultivating a Culture of Learning and Innovation:

Quality is built in by the people on the front lines. Bad quality is driven from the top down, usually by pushing for things the system is not capable of.

People can only perform within the bounds of the design of the system. Pressuring GM workers for better quality didn’t work any better than a VP at Tesla sending a memo to workers telling them to prove the “haters” wrong. Tesla employees can only perform as well as the system design. Different decade, similar problem, it seems.

https://www.vanityfair.com/news/2018/03/elon-musk-wants-volunteer-employees-to-help-prove-teslas-haters-wrong

How many Model 3’s can they build? That’s not 100% in control of workers. The system is designed to get the results it’s getting.

There was a big spike in production the last few weeks of the last quarter. I hope quality and safety didn’t suffer, as a result.

It’s a quality cliffhanger… I can’t wait to hear what happened next! Stories like these make me grateful to have a leadership team that cares about shipping a good product, not just shipping anything we can check off. It is incredibly frustrating to be asked to scramble for containment on the same problem over and over again in manufacturing – I can’t imagine how demoralizing it must be in a healthcare setting when the defects are happening directly to people you see face-to-face.

Thanks, Kate. I might publish the 2nd part of this story next week.

Scrambling for containment isn’t the best long-term solution… but that’s something I wish healthcare did better. It’s far too common that a problem occurs (a proverbial “fire”) and that fire appears to be put out… but the embers are still hot and the fire starts again. So, containing the fire from spreading and recurring right away is a good start.

Then, we can hope to do some root cause analysis and corrective actions that truly improve the system, preventing future fires.

Here is Part 2 of the story… more of the same:

https://www.leanblog.org/2018/04/part-2-20-years-ago-at-gm-the-quality-death-spiral-continues/

See comments via LinkedIn:

My dad was at Ford in the Deming-era, although he didn’t work in manufacturing. I have asked him about the “Quality is Job One” commercials, which I remember well as a kid. He said, in his typical way, “Well, it wasn’t true when they started saying it, but towards the end, I think we started to believe it!”

Dad was very fond of Don Petersen, who famously met with Deming on a monthly basis. (Again, he wasn’t a factory guy at all, and still had these impressions). He didn’t care for later Ford CEOs — clearly the Deming influence didn’t last.