I leave for Japan in two weeks, so I'm very excited about that. It will be my third trip with Kaizen Institute and I hope you can join us someday in the future. I'll be tweeting and blogging about it while there, especially during the official tour days, February 26 to March 2. I'll also be there a few days before and after. See past blog posts about the trips.

Hear Mark read this post — subscribe to Lean Blog Audio

While we visit Toyota and some other organizations that do a great job with Lean (or the Toyota Production System) and Total Quality Management practices (or some combination of those practices), one key lesson from the trip is that not all Japanese companies are the same.

Not all Japanese companies are the same. “Lean isn't easy” if you're a Japanese company. Toyota has created something special, since “Toyota culture” is not exactly the same as “Japanese culture,” as I've written about:

And see my friend Katie Anderson‘s post about this same topic from her time living in Japan.

Earlier this week, the Wall St. Journal wrote this article: “Companies Everywhere Copied Japanese Manufacturing. Now the Model Is Cracking.”

The subheadline reads “Concepts celebrated in business publications world-wide have been tarnished by a string of scandals.”

From the WSJ:

Kobe Steel Ltd. , Mitsubishi Materials Corp. and Subaru Corp. have all admitted in recent months to manipulating quality inspections, though all say no safety problems emerged. Takata Corp. declared bankruptcy last year after admitting to supplying more than 50 million defective vehicle air bags in the U.S. Mitsubishi Motors Corp.has admitted covering up vehicle faults and falsifying fuel-economy data.

Do scandals involving quality and ethical lapses involving companies including those and Nissan tarnish Lean and the Toyota Production System? No. That's as silly as thinking the Wells Fargo banking scandal tarnishes Silicon Valley (although the Valley does enough to tarnish itself).

Nissan Motor Co. the world's fifth-largest auto maker, disclosed in September that its Japanese factories let unqualified employees perform final quality inspections on some cars, a practice that might date back to the 1990s. During audits, foremen routinely provided trainees with badges from certified inspectors, the company said.

Does Nissan doing that tarnish the Toyota Production System? Of course not.

It's not just a matter of Nissan not being Toyota. The Toyota Production System and The Toyota Way are based on principles. These principles and philosophy aren't invalidated by problems at Toyota and they're certainly not invalidated by problems at other companies.

The Shingo Institute model, used by many organizations around the world, is also principles-based. Sometimes, companies (and the people that make up companies) don't live up to their stated values and principles.

Did the companies mentioned by the WSJ fail to “focus on process” and fail to “assure quality at the source?” It sounds like it. That doesn't invalidate Lean principles any more than me eating a cheeseburger invalidates healthy eating principles.

Daniel T. Jones, co-author of Lean Thinking and other books, wrote about this WSJ article on Linkedin, in part:

It seems like many Japanese firms did not fully understand these lessons – indeed there has always been a big difference between the Toyota's and many other Japanese firms. Indeed Toyota slipped up and the Gemba focus was lost sight of several years ago – and their response was to redouble their efforts to build awareness of the basics…

It sounds like he is saying there are times when Toyota has gotten away from their principles. Again, that doesn't invalidate the principles.

Michel Baudin also blogged about the WSJ article:

Countries Don't Have Production Systems, Companies Do

Back to the WSJ, which often gets things very wrong about Lean, wrote:

Japan's model, celebrated in publications such as Harvard Business Review, hinges largely on the concept of kaizen, often translated as “continuous improvement.” In practice, it means eliminating unnecessary activity, reducing excess inventory and using teamwork to fix problems when they arise.

That's a better definition than the times the WSJ implies Lean is only “just in time” production.

They continue:

It places enormous responsibility on line workers at the factory-floor level, known as the genba, to manage daily operations and generate innovation. Those workers, viewed by many Japanese as craftsmen, have traditionally been guaranteed jobs for life in return for dedication to their company's goals.

There's “enormous responsibility,” but Lean is not about just dumping responsibility on the front line employees. Leaders also have a responsibility to provide a system in which people can be successful, as I've heard former Toyota manager Darril Wilburn say.

The WSJ mentions the “andon cord” as an example of that responsibility, but it's really a two-way street. Workers are expected to pull the cord. Managers are expected to support them.

The problem today is that many Japanese companies can no longer afford the luxury of guaranteed lifetime employment for craftsmen on factory floors. And delegating so much authority to line workers has left companies exposed to fraud and corner-cutting, while giving executives room to shirk responsibility, according to management consultants and corporate lawyers knowledgeable about the problems.

What the WSJ describes there (fraud, corner cutting, and executive shirking) is not Lean. Some organizations have moved away from Lean principles (or possibly didn't embrace them at all).

Giving workers more responsibility does not automatically lead to fraud and corner cutting. Don't blame the workers — look at the system and the culture. And management is responsible for that.

If your organization is copying Toyota (or a health system) only because they appear to be popular, maybe you're doing it wrong. Maybe you should be adopting principles that seem timeless and self-evident (like the “Kaizen” idea of engaging everybody in continuous improvement). And maybe you shouldn't just be copying either. Learn from others, be inspired, but then go improve upon what you've learned and create your own system.

The WSJ article also mentions the late, great W. Edwards Deming:

Powering Japan's industrial might was a manufacturing model forged after World War II, when its companies sought to rebound by improving products for global buyers. Executives relied on an American management consultant, W. Edwards Deming, who advised companies to boost quality by empowering factory-floor workers to constantly focus on fixing problems.

The approach married well with Japan's ethics of hard work and attention to detail, and was widely adopted.

Deming didn't just “empower” factory workers. He tried reminding executives that “quality starts in the boardroom.” Senior leaders are responsible for the system. Workers can't perform better than the system that's designed.

I've used this quote in training classes:

“There is not a day I don't think about what Mr. Deming meant to us,” Toyota's then-chairman Shoichiro Toyoda said in 1980. “He is the core of our management.”

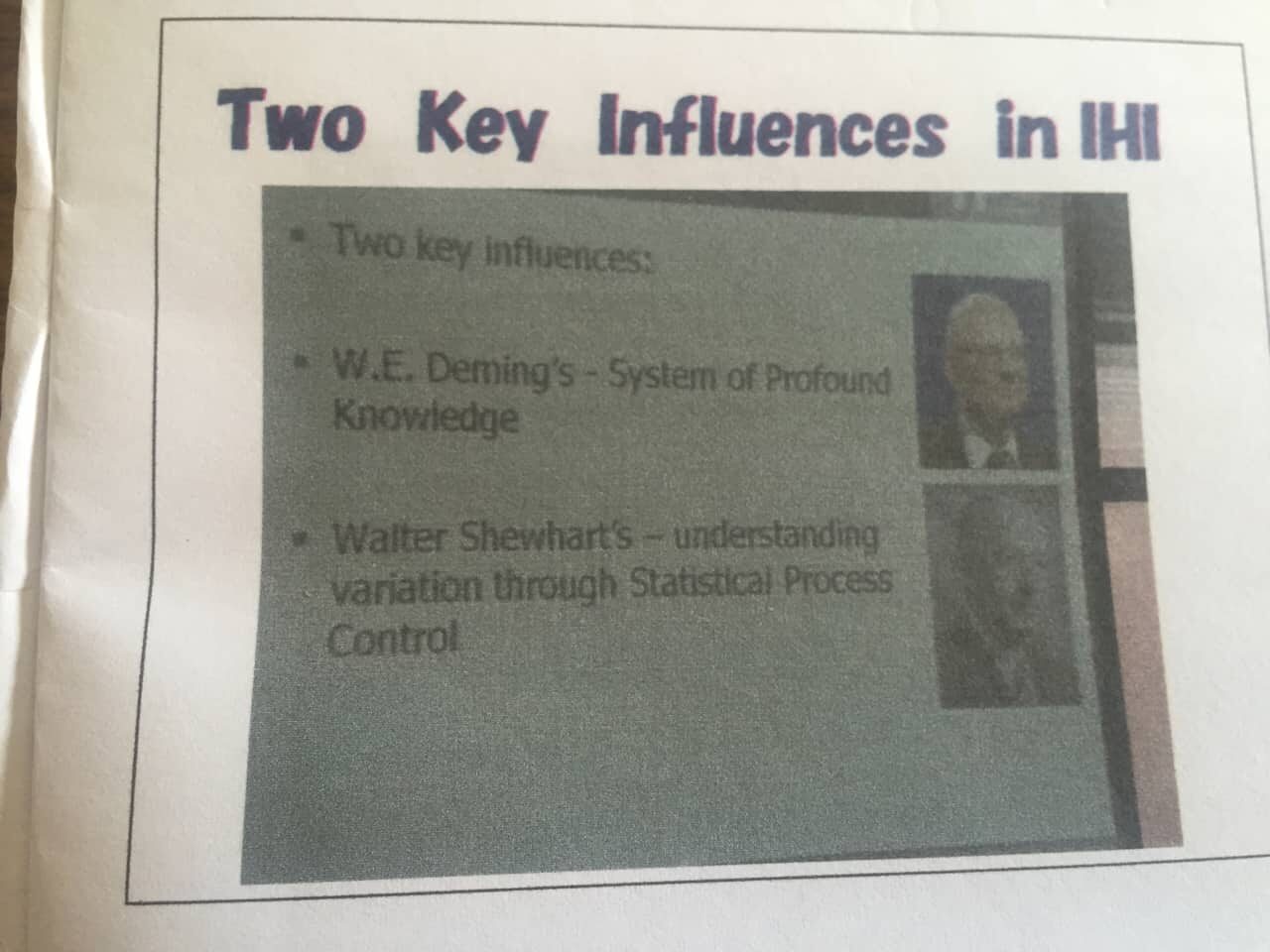

One Japanese hospital CEO I met in 2014 acknowledges this connection to Deming, as the hospital layered Lean practices on top of decades of TQM practices:

A clearer view of the slide:

When I worked for General Motors from 1995 to 1997, the Livonia Engine Plant supposedly lived by Deming principles that had been adopted a few years earlier.

But, they were no longer living by those principles (if they ever did). That doesn't invalidate the principles!

Final thought: It's my goal to honor the legacy of Deming and Shewhart, and what I've learned from them, in my upcoming book Measures of Success (that I'm currently writing).

Please scroll down (or click) to post a comment. Connect with me on LinkedIn.

Let’s work together to build a culture of continuous improvement and psychological safety. If you're a leader looking to create lasting change—not just projects—I help organizations:

- Engage people at all levels in sustainable improvement

- Shift from fear of mistakes to learning from them

- Apply Lean thinking in practical, people-centered ways

Interested in coaching or a keynote talk? Let’s start a conversation.

Tom Ehrenfeld also wrote this for the LEI “Lean Post:”

Is there a crack in the model of continuous improvement?

Thanks for citing my Planet Lean article on Japanese and Lean culture not being the same. One of the biggest takeaways for me from living in Japan for 18 months, and subsequent visits, is that not all Japanese companies have a kaizen mindset, and certainly the Toyota culture is unique.

I remember talking to Mr. Isao Yoshino, John Shook’s first manager at Toyota, two years ago about some recent scandals at Toyota and issues faced by other Japanese manufacturers. He told me that one of the biggest differences with Toyota is that it has a practice of “hansei” or deep reflection. The test for Toyota would be how it *learned* from its mistakes. He was not so sure the other companies had as deep of a practice of humility and reflection.

Yoshino’s reflection on these various issues across different Japanese companies was:

“If you believe you are perfect, you won’t find the answer. If you don’t believe you are perfect, then you are open to finding the answer. Once you are ready to accept that mistakes can happen, then you are okay because you will learn.”

(More found here: https://kbjanderson.com/toyota-leadership-lessons-part-5-if-you-believe-you-are-perfect-you-wont-find-the-answer/)

Your post got me thinking about my recent trip to Japan and was the basis of reflections in my latest blog post: https://kbjanderson.com/a-reminder-from-a-recent-visit-to-japan-lean-is-not-inherently-japanese/

I concur Mark. I posted this on the WSJ and sent a note to the two reporters, but they did not respond. Here was my comment. “Unfortunately, this article is mixing apples and oranges. Anyone who has deeply investigated highly effective improvement practices would know that MOST Japanese companies were never something to be emulated. Just like in the U.S. and all other parts of the globe, there are only a handful of companies that are highly effective at improving. Most do an average mediocre job of improving. While many companies use the same improvement tools as the elite, like having workers identify and act on problems, going to the Gemba, etc. Very few use these tools in a highly effective way. Even the elite struggle from time to time with doing this well, as Toyota has periodically experienced. There is a lot leaders can learn about what is really happening if they do go to the Gemba (where the action is) and see what is happening. Unfortunately this is also a challenge as our biases often hide the reality. I’ve written about these issues over the years. If interested you can find it.”

[…] The WSJ Overgeneralizes about The “Japanese Model,” Not All Companies Are Toyota by Mark Graban […]