A couple of people have asked me to comment on what's happening at Whole Foods. Or, I should say what's reportedly happening.

I've shopped a few times at the Whole Foods in Colleyville, Texas and haven't see the problems described in the two news articles I'll discuss here. But, that doesn't mean the problem isn't there in at least some stores.

The first story appeared in January:

‘Entire aisles are empty': Whole Foods employees reveal why stores are facing a crisis of food shortages

The reports say that many stores have “a crush of food shortages” that are frustrating customers and employees. Some jumped to blame Amazon for the problems after they acquired Whole Foods last year. But that's unfair.

Hear Mark read this post — subscribe to Lean Blog Audio

From Business Insider:

“But Whole Foods employees say the problems began before the acquisition. They blame the shortages on a buying system called order-to-shelf that Whole Foods implemented across its stores early last year.”

Employees are hoping Amazon can fix the problem.

There's an interesting Lean connection between Toyota and supermarkets. After World War II, Toyota leaders visited the United States and were fascinated by supermarket, particularly the “Piggly Wiggly” chain. Read this article about this bit of history.

Toyota was impressed by what we'd now call a “pull system,” where supermarket shelves were restocked from a back room and that back room was restocked from suppliers. This led to the kanban card system and intermediate inventory locations in factories are often called “supermarkets” since workers come and pull parts as needed.

It sounds like Whole Foods is trying to bypass the backroom and reduce the amount of time employees spend bringing food from the back room out to shelves.

“Business Insider spoke with seven Whole Foods employees, from cashiers to department managers, who asked to remain anonymous for fear of retribution.”

More about fear later…

Either the OTS system is badly thought out or they need to work out the kinks.

“At my store, we are constantly running out of products in every department, including mine,” an assistant department manager of an Illinois Whole Foods told Business Insider. “Regional and upper store management know about this. We all know we are losing sales and pissing off customers. It's not that we don't care — we do. But our hands are tied.”

It's good to reduce excess inventory, especially when it spoils. But, as I learned almost 20 years ago from a Japanese sensei, the first job of “just in time” is to make sure customer demand is met. The secondary goal is low inventory. I took that to mean we should have enough inventory but no more. Easier said than done.

Too many companies have really hurt themselves by thinking “just in time” means arbitrarily slashing inventory levels. That can get you in a lot of trouble. You need to have systems and supply chains that can support lower inventory. My MIT master's thesis was born out of a situation where a Kodak semiconductor operation really hurt itself and its premium digital camera business by reducing inventories to levels that were way too low to meet demand. They were also losing sales and pissing off customers (photojournalists).

“The company's executives have described the changes as cost-saving, and employees acknowledge that they have helped reduce food spoilage in stock rooms.”

Cutting costs but losing revenue doesn't seem like a good strategy. If your primary objective is minimizing food spoilage at all costs, you would have an empty store. Classic “Economic Order Quantity” (or EOQ) equations are meant to balance the cost of excess inventory with the cost of lost sales. Things are meant to be kept in balance. Neither extreme (too much inventory or not enough) is a good place to be.

And, yes, the back room is smaller: “25% of the size it was before the implementation of OTS,” the BI report says. But you need the processes to support that.

When I joined Dell Computer in 1999, they were about to build a new factory. A VP of manufacturing and supply chain declared, “The factory will have no warehouse!” Easier said than done. But, we had a team of people with almost a year to get the processes and technology in place to make that vision a reality.

The old Dell process was to have a factory warehouse that could send parts to the kitting areas or assembly lines. Now, the warehouse was small and Dell was famous for low inventory, but having ZERO warehouse was a challenge.

We designed a process we called Pull-To-Order, which reminds me of Order-To-Shelf. Except we all made it work with relatively few hiccups. Parts were pulled from a “Supplier Logistics Center” (SLC) or a shared warehouse that was just down the road from the plant. Dell forced suppliers to keep inventory nearby so it could be pulled every two hours based on KNOWN and SCHEDULED customer demand. I should write a longer blog post about our work at Dell sometime. I ended up being named on two business process patents through this work (here is one).

Update: To clarify my original post… the “known” demand was for those two-hour schedules. Orders were prioritized from the backlog of actual customer orders that were deemed “ready to build” because all parts were available. From the broader supply chain perspective, material was shipped from suppliers to the SLCs based on forecasts – a bigger challenge.

Whole Foods is dealing with UNKNOWN customer demands, even though I'm sure they have forecasts and data that help guide those decisions. But, variation can be painful.

“A reduced back stock means that any unexpected increase in shopper demand or a product-shipment delay can result in out-of-stock items across every department, multiple employees said.

“If a truck breaks down and you don't get a delivery, then you have empty shelves,” an assistant manager of a Chicago-area Whole Foods said.

My MIT master's thesis looked at three types of variation for inventory planning purposes:

- Demand variation

- Production lead time variation

- Quality / yield variation

Whole Foods might suffer from all three types of variation.

With all of the shortages and complaints, I'm glad that nobody has called this approach “Lean.” Nor have they referred to it as “Just In Time.” There's no evidence that any of this OTS approach is inspired by Lean or Toyota. Because it doesn't sound like Lean to me.

Employees fear the “write ups” and “militaristic” approach that is taken by managers (and I'm glad nobody is calling this a “standard work audit” because, again, this doesn't sound like a Lean culture to me.

“Whole Foods gets stores to comply with OTS by instructing managers to regularly walk through store aisles and storage rooms with checklists to make sure every item is in its right place and there is no excess stock. If anything is amiss, or if there is too much inventory in storage, the manager in charge of that area of the store is written up. After three write-ups, they can lose their job.”

It sounds like “excess stock” and “too much inventory” aren't the problem.

Threatening to fire people isn't the Lean approach. Lean leaders design systems that allow people to be successful. And those leaders collaborate to help people improve processes instead of threatening them.

Sounds like a big disconnect:

Another worker explained: “We think of it as punishment. They think of it as a way to correct errors.”

This article explains more:

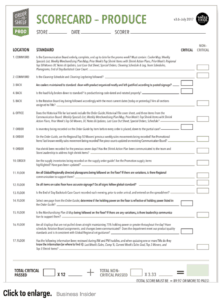

‘Seeing someone cry at work is becoming normal': Employees say Whole Foods is using ‘scorecards' to punish them

Process checks, audits, scorecards, and metrics should be used for understanding and improving, not punishment.

They say many employees are terrified of losing their jobs under the new system and that they spend more hours mired in OTS-related paperwork than helping customers.

I'm not sure how this helps Whole Foods in the long run:

“The OTS program is leading to sackings up and down the chain in our region,” said an employee of a Georgia Whole Foods. “We've lost team leaders, store team leaders, executive coordinators and even a regional vice president. Many of them have left because they consider OTS to be absurd. As an example, store team leaders are required to complete a 108-point checklist for OTS.”

Click on the article to view the audit sheet.

It's good for leaders to walk the process and to check to see if standardized work is being followed. But, if there appears to be a problem, leaders should be asking “why?” and “how can I help?” instead of asking “who” gets in trouble.

I hope they can get this fixed. I hope nobody, including the WSJ as they tend to do, starts blaming “Lean” or “JIT” for this. Some articles use the word “lean” as a synonym for “not enough inventory,” but that's not what “Toyota Lean” is all about.

I hope Lean (or attempts at Lean) aren't causing problems like this in your hospital or factory.

What do you think? Please scroll down (or click) to post a comment. Or please share the post with your thoughts on LinkedIn – and follow me or connect with me there.

Did you like this post? Make sure you don't miss a post or podcast — Subscribe to get notified about posts via email daily or weekly.

Check out my latest book, The Mistakes That Make Us: Cultivating a Culture of Learning and Innovation:

Perfect example, Just in Time means having the material ready when it is needed at the moment the CUSTOMER wants it. It doesn’t mean ZERO inventory but rather knowing what drives demand and responding to it. Kanban sizes should be adjusted regularly based upon customer demand patterns.

Thank you for your excellent comments about the Whole Foods situation. Other chains face similar problems. I’m looking forward to reading your comments again and following the links in it. True Lean production is valuable to know and do!

It’s a sad situation, especially when I think of WFM in the early days as a place where employees seemed very happy and engaged. Far too often, when organizations start looking to reduce costs, they get so focused on it that they start to think of cost-cutting as their purpose. WFM’s mission statement refers to setting the standard of excellence for food retailers. I can’t think of anything that dissatisfies customers as a “standard of excellence.”