TL;DR Summary: “Employee 1” (the guy who pushed the “wrong” button) got fired. But the FCC report says: “The report finds that the false alert was not the result of a worker choosing the wrong alert by accident from a drop-down menu, but rather because the worker misunderstood a drill as a true emergency. The drill incorrectly included the language “This is not a drill.” So, the language from the drill didn't meet the standard for what the drill language is supposed to say. So, how is it fair to fire the worker who heard “this is not a drill?”

Hear Mark read this post (subscribe to the podcast):

Last month, I blogged about the false “inbound missile” warning that was sent in Hawaii.

Since early reports involved confusing or poorly designed software screens or menus, the situation screamed “systemic problem” to me. As I wrote about, I hoped that the resolution to this scenario wouldn't involve simply firing somebody and saying “problem solved” as so often happens in healthcare and other settings.

Yesterday, we saw news stories about the formal inquiry and report that was released.

You can read the report titled “FALSE BALLISTIC MISSILE ALERT INVESTIGATION FOR JANUARY 13, 2018“ as a PDF.

You can also read this CNN story: “Hawaii false missile alert ‘button pusher' is fired“

When I saw the headline, I thought, “Oh no, they fired somebody and blamed them.” It seems like that's sort of the case, but not exactly. That's not the whole story. You have to read beyond the headline.

From CNN:

“The Hawaii Emergency Management Agency employee who triggered the false ballistic missile alert earlier this month has been fired, the state adjutant general said Tuesday.”

Why was he fired?

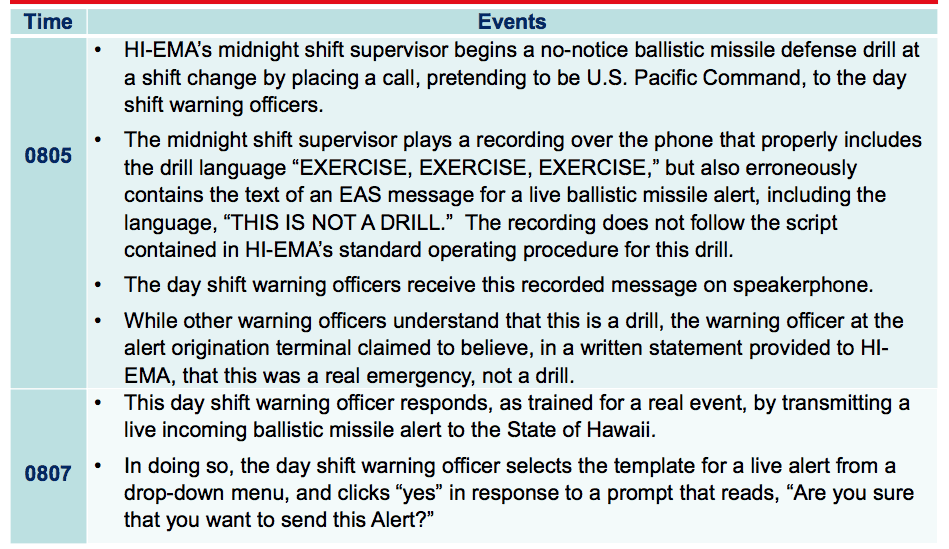

“The unnamed employee said he didn't know it was an exercise, even though five other employees in the room heard “exercise, exercise, exercise, which indicates that it is a drill,” an investigating officer told reporters.”

Why didn't the employee know it was an exercise when the others did? Was he distracted? Out of the room? Had headphones on?

It sounds more complicated than that:

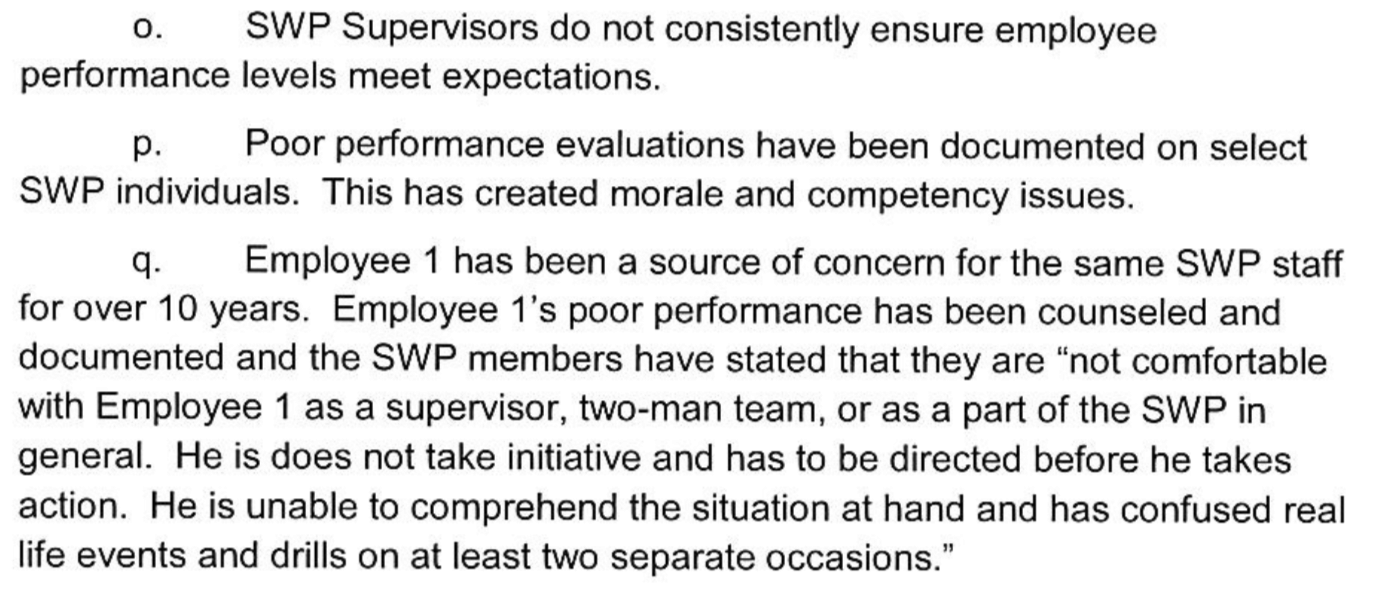

The employee “had a history of confusing drill and real-world events,” Oliveira said.

Was This a Known Problem Employee?

So if that's the case, that the employee had a bad “history,” why was the employee still kept in that position? There are possible reasons for why they couldn't easily fire him (union protection, etc.) but it seems he could have been reassigned to something less risky.

If leadership's not properly addressing a “problem employees” then that makes it a systemic problem. To me, it's the same way it becomes a systemic problem when hospital leaders know a surgeon has a long history of being abusive or they know an anesthesiologist is diverting drugs… but the leaders don't do anything about it.

If the fired employee was that unfit for duty, why weren't Hawaii emergency management leaders more proactive? You can't just fault the individual, you also have to look at the system.

The original reports made it sound like the problem was what medicine would call a “slip” or a “mistake ” — clicking the wrong place on the screen. The new report makes it sound like what you might call an intentional act, albeit it the incorrect one, which is a form of “mistake.”

“Slips can be thought of as actions not carried out as intended or planned, e.g. “finger trouble” when dialing in a frequency or “Freudian slips” when saying something.

Mistakes are a specific type of error brought about by a faulty plan/intention, i.e. somebody did something believing it to be correct when it was, in fact, wrong, e.g. switching off the wrong engine.”

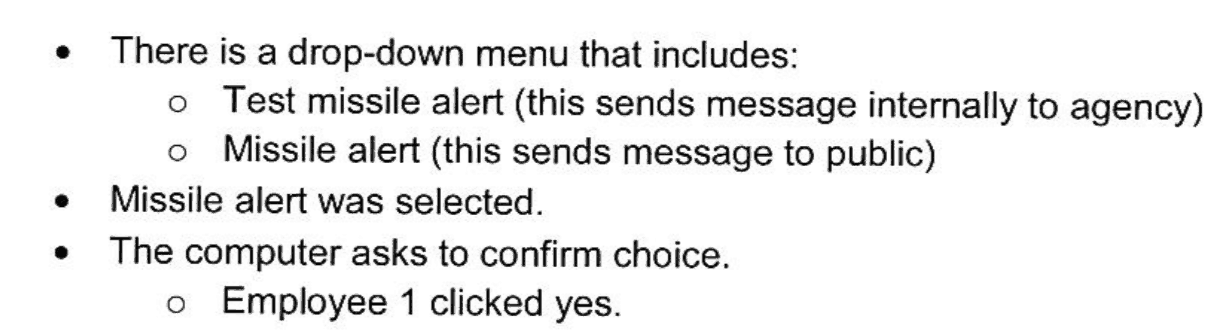

From the report, they describe the intentional (albeit mistaken) action:

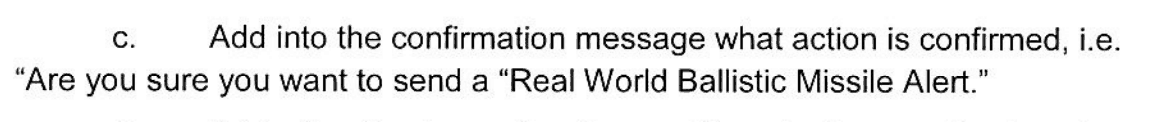

The report, by the way, recommended making the vague “are you sure?” message into a more specific “are you sure you want to send an alert?” American Airlines, at my suggestion, made a similar improvement to its flight cancelation confirmation messages.

So, again, it wasn't a case of “I meant to click test and accidentally clicked alert.” It was more like “I meant to click alert, but for incorrect reasons.” That's a different type of “human error.”

Was It a Drill or Not?

The fired employee claims they heard “this is NOT a drill” being announced, but nobody else working with him heard that.

This NPR story says that the recording played by the supervisor DID say “this is not a drill.”

The report finds that the false alert was not the result of a worker choosing the wrong alert by accident from a drop-down menu, but rather because the worker misunderstood a drill as a true emergency. The drill incorrectly included the language “This is not a drill.”

Why would you blame Employee 1 for hearing “this is not a drill” and then acting accordingly?

If anything, there was confusion and Employee 1 can't be blamed for that.

The FCC report (which I hadn't seen when I first wrote this post) says definitively that “this is not a drill” was said.

Why did the recording not follow the standard? Who created that video? If we're going to blame anybody, do we blame them? Do we ask WHY the recording didn't follow the standard? How wasn't that detected previously?

Blaming Employee 1

The employee was a known problem, according to the report:

Beyond the employee's alleged problems, there are management problems galore there – not having a performance evaluation or management system. Why didn't management act if other team members had zero confidence in him?

But There are Systemic Factors

The report cites systemic factors, as well:

“that insufficient management controls, poor computer software design and human factors contributed” to the alert and a delayed correction message

The leader, Mr. Miyagi, has resigned:

Maj. Gen. Joe Logan, Hawaii's state adjutant general, said Vern Miyagi, administrator of the state emergency management agency, resigned Tuesday.

Miyagi accepted full responsibility for the incident and the actions of his employees, Logan said.

It's good to see a leader take responsibility for the system they created or oversaw, unlike leaders at Wells Fargo and the VA who only blamed employees and threw them under the bus.

Employees claim, in the report, that training on their new system (installed in December 2017) was insufficient (another systemic problem that belongs to leadership):

Training was required, but there are no formal records of who was trained. The fired employee supposedly completed the course. But, having a course doesn't mean the training was completely sufficient. Does the training follow the proven “Training Within Industry” methodology that includes steps to ensure and confirm that the student has really learned and is actually capable of doing the work properly? That probably wasn't used.

Bringing it back to hospitals again, a lot of training is “done” (check the box) but isn't really effective. I hear similar complaints about EMR/EHR training all the time.

Back to the Hawaii case, other employees are being punished, which again makes me wonder… again from CNN:

Another employee is in the process of being suspended without pay and a third employee resigned before any disciplinary action was taken, Logan said.

It's unclear why those other employees were being punished.

One factor in the delay for getting the “all clear” message out was this fired employee refusing to respond:

At one point, one employee directed the fired employee to send out the cancel message on the alert system. But the fired employee “just sat there and didn't respond,” the timeline said. Another employee seized the fired employee's mouse and sent out a cancellation message.

The FCC also points to other systemic factors (things that are owned by senior leaders, not frontline workers):

The state “didn't have reasonable safeguards in place to prevent human error from resulting in the tranmission of a false alert,” the statement said. The second main problem, Pai said, was there was no plan of action if a false alert went out.

What's the Just Outcome?

So, I'll again raise the issue of whether it's “fair and just” to have fired that employee. What do you think?

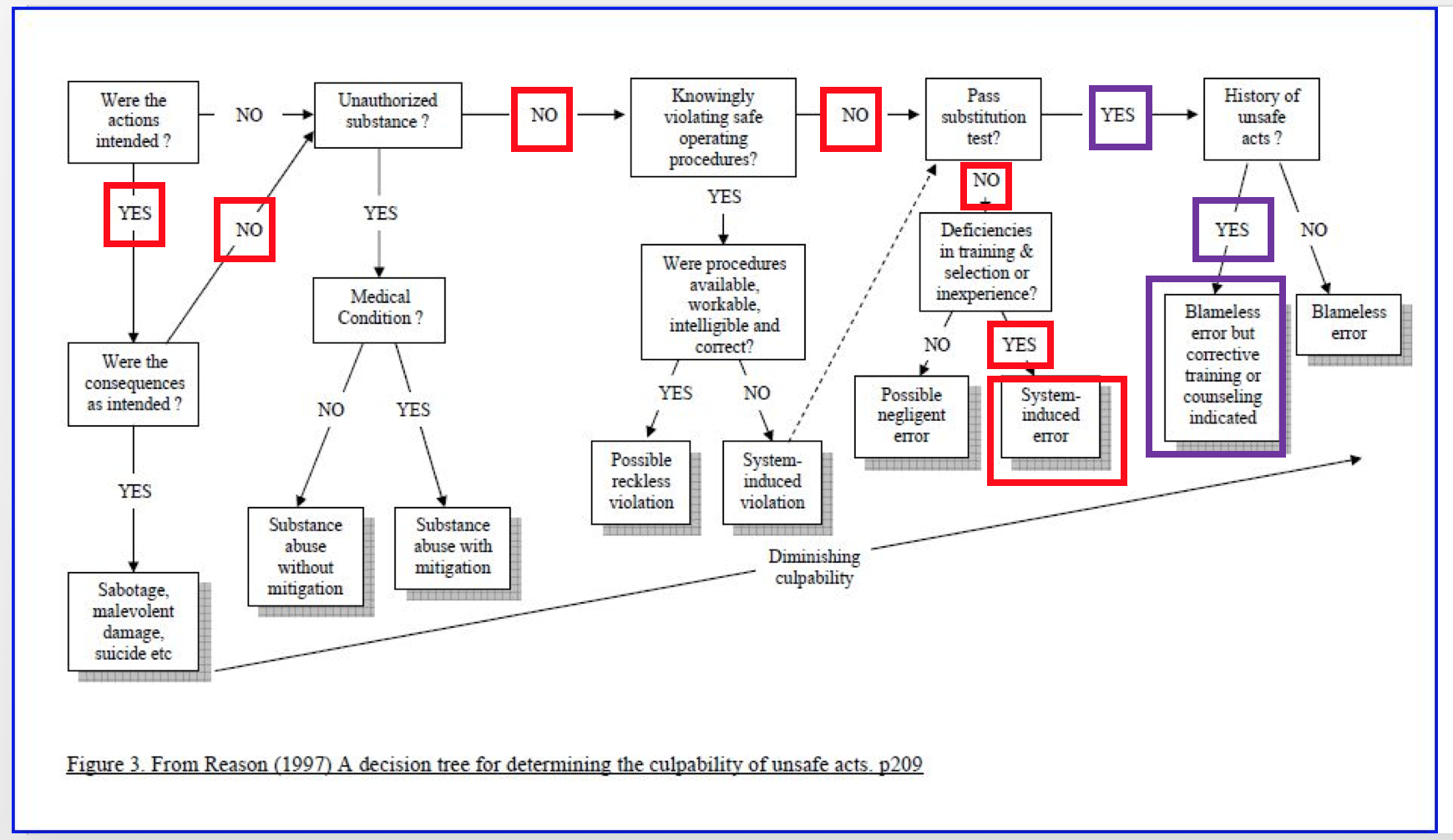

What would happen if you used the flowchart of the “Just Culture” algorithm?

The red boxes are my attempt at answering the flowchart questions… until the “pass substitution test?” when the red and purple boxes diverge into the less obvious answers. Neither outcome of the flowchart really points to firing being a “just” outcome.

In my best guesses from the report, it seems like it WAS an intentional act, but was NOT intended to erroneously cause panic. If there's no substance issue, it doesn't seem like he “knowingly” violated procedures. Something caused him to think the scenario was real.

If the answer to the “substitution test” is “no” (meaning a colleague wouldn't have done the same thing), and there are training deficiencies, the Just Culture algorithm would call this a system error. But, it sounds like the employee's incorrect and strange behavior was more than a training situation. But, if there had been a “history of unsafe acts” (or other strange behavior), is that primarily a system issue?

Clearly, there's something strange about the whole history and the behavior of that employee. But if it was a known problem, on some level, why wasn't it addressed?

Why was the drill run during shift change when, as the report says, there was “confusion of who is in charge and which shift is executing the checklist actions.” Maybe it's a good thing to test and simulate if somebody really does launch an attack during shift change. Hopefully, they can improve that aspect of the system going forward.

Again, if it's true that the supervisor or the recording said verbally “this is NOT a drill,” then blaming Employee 1 is totally unfair and unjust to them.

Firing and punishing people alone won't prevent future problems, as evidenced by all of the recommendations in the report about improving processes, software, management systems, and culture. Firing or punishing somebody is certainly easier than improving systems. But, improving systems is more effective.

What do you think? Please scroll down (or click) to post a comment. Or please share the post with your thoughts on LinkedIn – and follow me or connect with me there.

Did you like this post? Make sure you don't miss a post or podcast — Subscribe to get notified about posts via email daily or weekly.

Check out my latest book, The Mistakes That Make Us: Cultivating a Culture of Learning and Innovation:

Thank you so much for your play-by-play of this incident and the “Just Culture” flowchart. I ran a recent work scenario through the flowchart and found it enlightening.

Could you offer some thoughts on what sounds like “Lean-gone-bad” at Whole Foods.

http://www.businessinsider.com/how-whole-foods-uses-scorecards-to-punish-employees-2018-1

Thanks, Oscar.

That sounds like a really bad situation at Whole Foods.

I haven’t seen the word “Lean” used to describe what they’re doing.

Scorecards or checklists should be used for improvement, not for punishment.

This does sound like “just-in-time” that’s poorly understood and badly implemented:

‘Entire aisles are empty’: Whole Foods employees reveal why stores are facing a crisis of food shortages

I plan on blogging about this more. I should go to my local Whole Foods store this weekend.

Here is my blog post on Whole Foods, Oscar:

https://www.leanblog.org/2018/02/whats-going-whole-foods-doesnt-sound-like-lean/

From the WSJ:

Former Hawaii State Worker Says He Thought Missile Attack Was Real

Ex-Hawaii Emergency Management Agency worker says he didn’t hear that call was a drill when he sent false alert

This all screams “system problem.” If Employee #1 was confused and unresponsive after sending the alert, maybe it’s because he thought they were about to be nuked.

If he was really THAT much of a liability, then shame on the agency for keeping him in that job.

From the Washington Post:

‘I’m really not to blame’: Fired Hawaii worker says false missile threat was ‘system failure’

There is video embedded in that link above.

Another story, with video from NBC:

Hawaii emergency management worker who sent false missile alert: I was ‘100 percent sure’ it was real