If this post is a bit of a rant, I apologize. The problems here are avoidable and fixable. That's one reason I get so fired up about patient safety. Patient harm is not an unavoidable natural disaster, like a hurricane. It's a man-made problem… and people can solve it. See this recent post and these examples. That's my passion… more so than pushing Lean as a solution… I want us to solve the problem of harm and death caused by preventable medical errors, which are caused mainly by bad processes and bad systems…

I was on the road yesterday and picked up the business traveler's hometown paper, USA Today.

Here was the headline that greeted me and I wasn't surprised… my thought was “which hospital is being highlighted this time?” Again, I'm reminded of the line from the movie “Fight Club” — it's a major one. I also thought, “There was room for an ‘s' at the end of the headline… why are they singling out one hospital when this is a widespread problem?

What's noteworthy here is that it's MedStar Washington Hospital Center. I guess systemic patient safety problems are supposed to matter more when it's a hospital that treats D.C.'s political elites.

Patient safety caused by preventable error is a national problem, if not a global one, when you look at the stats.

Here is the online version of the article, with the headline:

“Official trauma hospital for D.C. power brokers cuts costs amid sewage leaks, safety problems”

Here is a video with a retired trauma surgeon talking about how good their reputation was (was that ever really the best indicator of quality and safety?), construction that may have led to the sewage problems, and how cost cutting and layoffs can lead to quality problems (the latter being an issue I have blogged about a lot).

Being overworked (and/or understaffed – same thing) is going to hurt quality and fatigue and overwork are going to lead to safety issues for staff or patients. The same is true in an auto factory (look at complaints about Tesla) or a hospital.

Lean is about reducing waste and making work easier. It's not about cutting staff and making people figure it out (or letting them struggle). I don't know much about “Lean” efforts at MedStar, but Christina Saint Martin, who is well known in Lean healthcare circles, formerly of Virginia Mason, was there at MedStar from 2015 to 2017 and recently left to join Baylor Scott & White in Texas). It's far from the most important aspect of this situation, but I hope nobody there would blame Lean for their problems. It wasn't mentioned in the article.

Lean should be part of the solution to situations like this, of course.

Even at full and proper staffing levels, poor processes and systems can lead to medical error and harm. Understaffing is like throwing gasoline on a fire.

From the article:

“Sewage that leaks down the walls and on the operating room floors is among the many problems at the go-to hospital for Congress and the White House, according to interviews and documents obtained by USA TODAY.”

Sewage leaks aren't the typical problem I see or hear about. That makes patient safety risk seem like a rare event. Not every hospital has sewage leaks. But, I'd say most every hospital has daily risks that are less visible (or harder to smell).

It seems that the hospital and its leadership failed in addressing the sewage problem quickly and effectively. It smells like there were more workarounds than root cause solutions.

“Buckets have been used to catch water leaks from ceilings at least twice during surgeries. These were the same ceilings through which sewage leaked.”

A bucket to catch the leak is, at best, a “short-term countermeasure.” There might have a been a bad system design choice to put some ORs in the basement below bathrooms, but not every bathroom leaks sewage. Was that a construction issue, as suggested by the surgeon in the video, or was maintenance not done properly?

In another example:

“Portable fans were used to eliminate strong “porta potty” odors in the operating rooms and to dry them more quickly, even though federal studies show fans can spread bacteria in the air.”

That sounds, again, like firefighting instead of good problem solving. And, it seems like an example of a countermeasure that caused at least the risk of another problem.

Quite literally, the shit hit the fan…

The hospital now says:

“all pipe issues have been corrected.”

I hope that means, then, that the sewage problem has been corrected.

Other than sewage leaks, the article describes the type of process breakdowns and poor problem solving that you might see more frequently in other hospitals:

“Employees in “protective” foot coverings scurried back and forth between sewage-soaked operating rooms and surgical instrument storage areas into hallways as patients passed on gurneys and lined the halls.”

This is something that bothered me since the very first time I was able to spend time in a surgical area. I was taught and shown “proper” protocol about changing into scrubs and what to do with head and foot coverings. I was told not to wear shoe covers out of the surgical area.

But, I constantly saw experienced O.R. staff wearing their head and foot covers throughout the hospital, including the cafeteria. What were they tracking out of the O.R. with them? Did they always change into fresh covers when they re-entered the surgical area? There was an apparent breakdown of process and standards. Who was managing that?? Who was responsible for maintaining standards?

I'd call that a “leadership problem” not a “bad staff” problem. A “Lean” organization would have better adherence to process. When they see a standard not being followed, they'd start by asking “why?” instead of blaming staff. They'd work together to ensure staff can do the right things the right way.

Back to MedStar:

“Flies are a regular problem in operating rooms and the insects landed on open wounds at least twice and often elsewhere on patients.

“This describes a hospital that is out of control,” says Lisa McGiffert, director of Consumer Reports‘ Safe Patient Project.”

The surgeon in the video talks about their reputation. Is that really a patient-focused mindset?

You hear the pride in the CMO's comments:

“In an interview, the chief medical officer, Gregory Argyros, described MedStar Washington as “the most important hospital in the most important city in the most important country in the world.”

Pride cometh before the fall, as they say?

This “most important” hospital gets very bad scores from CMS Hospital Compare (2 stars out of 5) and Leapfrog Group (a “D” grade). That hasn't harmed their reputation?

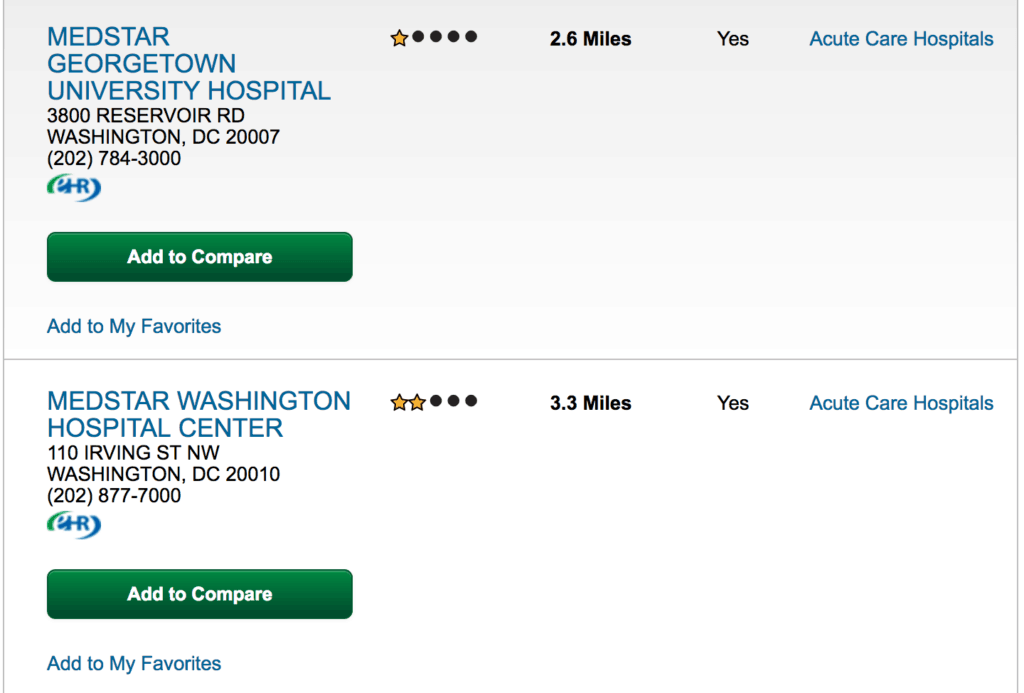

MedStar Georgetown scores worse with CMS:

Some of their surgical quality measures are “no different” or “worse” than the national rate and a lot of the infection rate data seems missing.

The Leapfrog Group page for the hospital says they declined to participate, so I'm not sure where USA Today gets the “D” grade from. Maybe that was from previous years when the hospital DID participate?

The hospital has been in cost cutting and layoffs mode. And, nurse turnover is pretty high… not a good indicator for quality and safety:

Against this backdrop, Washington Hospital Center was grappling with a $16 million shortfall after the most recent fiscal year ended in June, which prompted a memo alerting department heads that they need to cut millions from their budgets. Physicians, including anesthesiologists, left the hospital under confidential agreements although Argyros denied layoffs affected anyone involved in direct patient care.

About 400 nurses out of 1,780 left their jobs last year — up from about 300 a year between 2010 and 2015, according to data compiled by National Nurses United, which represents them. That comes to about a 22% turnover rate, compared to the 14% rate provided by hospital spokeswoman Donna Arbogast.”

Hospitals always say “patient safety is our top priority” and they always say layoffs “won't affect patient care.” Do those statements always ring true?

Hospital “defenders” (some might use the word “apologists”) say it's unfair to blame them for high infection rates. But, I'd say you CAN blame a hospital for bad process.

“In an internal memo to staff after an earlier USA TODAY story about the hospital, MedStar's David Mayer, the vice president of safety and quality, said it is improper to link in any way someone shot with a “dirty bullet from a dirty gun on a dirty ball field” with a hospital's high overall infection issues with a hospital.”

Referring to Congressman Steve Scalise, who was shot on a baseball field. Scalise did get an infection. Who knows why.

The “our patients are sicker” argument is a pretty common excuse in healthcare.

Leapfrog has a different view on the hospital:

“Our data suggests that patients are more likely to be harmed or die unnecessarily from an infection at this hospital than most other hospitals in the country,” says Leapfrog CEO Leah Binder.

The CMO talks a better game about aiming for zero harm:

“Argyros, who says the hospital is on a “high reliability journey,” confirmed the four retained foreign objects and said they included a sponge, a rubber retractor, a piece of a catheter and a “tiny piece” of a drill bit.”

“We need to accept no less than no patient harm,” Argyros said in a recent interview at the hospital. “It's really all about the outcomes. If outcomes are not good, we haven't met the mission.”

He says it's about the outcomes. Sure… but maybe focusing more on the process and better problem solving are some of the keys to achieving better outcomes?

The article mentions many examples of process breakdowns:

“A 102-page D.C. health department inspection report from last September highlighted examples of nurses failing to wash hands after treating wounds and not wearing protective clothing. Under a negotiated corrective plan, the hospital was required to develop a policy to prevent infections, including guidance for employees on things including how to keep their hands clean, use gloves and carry trays into patient rooms.”

I wonder how effective the “policy” countermeasure is.

The article also alludes to a culture of fear, which, again, is not good for quality and safety:

“As Scalise's operating room was being closed off for sterilization two days after his last surgery this summer, a doctor who asked to remain anonymous for fear of retribution said he saw liquid stool mixed in with other sewage on the floor. That suggested to the physician that the leak didn't just happen. As the room was being cleaned, a surgical procedure was taking place about five feet away in room No. 12, the doctor added and a document reviewed by USA TODAY indicates.”

Does anyone know how to get a copy of the 102-page report that the USA Today reviewed?

What are your reactions to the article and the situation? To me, it seems like a pattern of a splashy headline that asks “what's wrong with THIS hospital?” instead of “what's wrong with hospitals, more generally?”

As an aside, some of you might remember that I did a podcast interview with a filmmaker who was working with MedStar to make a documentary about IMPROVING patient safety.

I contributed to the Kickstarter campaign for the film. The film has not yet been completed. They are trying to get more funding, now from PBS. They might need to update their film, you know, because of the hospital's “reputation?”

Please scroll down (or click) to post a comment. Connect with me on LinkedIn.

Let’s build a culture of continuous improvement and psychological safety—together. If you're a leader aiming for lasting change (not just more projects), I help organizations:

- Engage people at all levels in sustainable improvement

- Shift from fear of mistakes to learning from them

- Apply Lean thinking in practical, people-centered ways

Interested in coaching or a keynote talk? Let’s talk.

Join me for a Lean Healthcare Accelerator Trip to Japan! Learn More

There is so much to react to in this.

We once had an office get drenched due to a water pipe burst. It took out a couple computers and soaked some clothes and papers.

In our pursuit of being a high reliability organization, having situational awareness over something so uncommon was not on our radar. Building structural risks is not something assessed every day by our clinical team. I would bet the surgeons and or nurses don’t have processes to check either.

From a systems perspective I wonder how the building and engineering department had preventative maintenance and inspections of the facility. I have heard situations where support teams like Engineetin are overburdened because all funding go to direct care providers. Those decisions add risk or extra work on clinical teams.

However – smell and visible liquid or debris is something they could have reacted to as an abnormality. I don’t understand why they would continue when something was clearly different. Sometimes the desire to care for patients inspires folks to continue despite the risks. Clearly a case of good intentions still risking harm for patients.

Revenue drivers could also be a systemic pressure to continue surgeries despite the risks. A hospital of that size I’m sure has more than one OR. I can’t tell if all were effected instead of just one or two.

Interesting how much emphasis is put on reputation data. That is only good to get people in the doors from a marketing perspective. What truly counts is the outcome data for patients.

The article does say they shut some rooms for some period of time. But it also implies the problem wasn’t really solved before they reopened them.

In our current system, “reputation” is still not a function of patient safety and quality data. I’ve pointed out before that US News & World Report hospital rankings still place too much weight on reputation. It’s circular logic. They aren’t necessarily famous because they’re safer. Being able to handle a complex trauma case is one form of quality. But that doesn’t mean they are good at other types of quality, including infection control.

As a former hospital CEO, and Lean practitioner, I can tell you, without reservation, as you (Mark) have said before, and I have said very often, this is a “leadership problem.” Why? because every problem in a hospital is a “leadership problem.” It also strikes me as a clear case of “the emperor has no clothes.” The leaders at this hospital have been so conditioned to believe their “reputation” that they forgot the basics. Now, they are focused on excuses. There are only two scenarios…The CEO and leadership team did not know, (leadership problem) or the did know and did nothing about it, (leadership problem).

There is another side to this. Every hospital has an Infection Control department of some sort. In most hospitals, everyone hates Infection Control. Why? Because they are always correcting staff and asking them to wash their hands, improve the use of Personal Protective Equipment and other “nit-picky” things. Clinical staff, especially physicians, hate to be told what to do and how to behave. So, it is incumbent on the CEO and Leadership team to ensure that Infection Control has priority.

CEOs, if they know what is good for them and their hospital prioritizes Infection Control.

If these blatant violations are happening in a surgical suite–IC unequivocally wants it shut down and fixed. Obviously, leadership did not shut it down! And now they are up to their eye-balls in…well you know what I mean. I guarantee somewhere in this hospital is an Infection Control nurse saying, “I told them this would happen!”

Here is the letter that the president of the hospital wrote to USA Today:

I cannot find it online.

Their “commitment to quality” is represented in their two-star CMS rating and Leapfrog “D?”

The president says the sewage incident was “handled immediately.” Is that what he was told? The article suggests this was an ongoing problem.

It’s not factually correct to say the Joint Commission inspects “every inch” of their hospital. That’s useless hyperbole.

He blames the paper and gives platitudes… not exactly owning the situation, eh?

Here is the hospital’s “Open Letter to Our Community.”

They blame “transparency” for the reporter painting an unfair picture.

This same transparency leads them to NOT participate in the Leapfrog Group ratings process?

BRAVO!, Mark.

Putting this situation in a Deming context, it sounds like hospital(S) are “perfectly designed” to have things that “shouldn’t” happen…happen:

https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/you-perfectly-designed-have-things-shouldnt-happen-davis-balestracci?published=t

But, as is obvious from the article, one has to be very careful how that message is delivered to defensive executives. And if one tries, “Dr. Deming says…” I guarantee you WILL get shown the door!

Education on how to respond appropriately to similar situations should be part of ANY MBA program (I’ve designed and taught a course for one):

http://www.linkedin.com/pulse/even-harvard-mba-coos-need-realize-its-all-variation-balestracci?trk=mp-author-card

If you say “As Dr. Deming says,” the response might be “Who?”

So you, too, are noticing that his reputation and philosophy seem to be, in hospital parlance, “circling the drain”? :- ) [but, really :- ( ]

Actually, his philosophy is sound…and robust. I stand by it in my consulting, but I rarely (1) invoke his name in hushed tones, (2) opine about the “profundity” of his System of Profound Knowledge (which comes across as too pretentious for words to an audience), or (3) (Sorry, Mark) do the Red Bead experiment (as in “never”).

Davis – I wouldn’t go so far as to say “circling the drain.” I think Dr. Deming is pretty much a non factor in most of today’s hospitals. People have heard of him and they’ve been taught about PDCA/PDSA (whether they are encouraged to practice it or not)…

Dr. Deming was incredibly influential on a generation of healthcare quality leaders like Dr. Don Berwick and they’ve passed along some of his lessons, but I don’t think the Deming name has much caché, sadly.

I agree his philosophy is sound and robust.

I agree the SoPK name is off putting…

Why don’t you use the Red Bead Experiment? I get consistent feedback that it’s eye opening… I use it as a way to introduce some very practical methods like Process Behavior (SPC) Charts… so it’s not just a standalone exercise.

I read something from 1986 the other day where Dr. Deming himself called the Red Bead thing “a stupid experiment” — but “one you will never forget.”

Regardless of the audience, people realize they have “red beads” in their own workplace… and they need to find new ways of managing and improving systems instead of just demanding better performance.

Mark, I pretty much agree with you about SoPK,that and many things in TNE and the 3 editions /revisions that came out in the year after his deathward construct of the folks “hovering ” around him those last few months,With the global bloom of Scientific Management that is at the root of organizations today that excluded “Humanity” . When Uneo brought it to Japan in 1911returning from Harvard “humanity was intrinsically included because of the paternalism in the culture,

I view designs work as providing the humanity,example joy/pride in work/7deadly diseases.

I was at gemba with the Lean Director of a client hospital. I noticed some equipment staged in front of a hand-washing station so I asked her about their hand washing initiatives. She said (and I’m tryouts by to quote as accurately as possible), “we tried something with that a couple years ago, but it didn’t stick”.

I’ve heard VP’s adamantly swear they were committed to clinical excellence, but feign helplessness when a patient had to wait a month and a half to get an appt to get a pre-cancerous mole examined. Some people, CEO’s and lean leaders alike, have no business being in healthcare.

But lean alone isn’t the answer. High-performing “lean” hospitals still struggle with clinical quality and patient safety. Thedacare is in the bottom quarter of hospitals for HAC’s, approx bottom third for VBP, and barely top half for serious complication rates. As the commenter above said, a culture that embraces infection control rigor and mandatory compliance to safety measures can separate a patient between a clean bill of health and sepsis

It’s easy to say “we are committed to clinical excellence” or “patient safety is always our top priority” — but those are far too often empty words.

What data are you looking at for ThedaCare? CMS data?

You say “Lean alone isn’t the answer” – maybe even the vaunted ThedaCare isn’t yet at Toyota like levels of performance? Wouldn’t a truly Lean culture “embrace infection control rigor?”

I don’t know if mandating compliance is the right mindset, as opposed to engaging people and making it easy for them to do the right things… again, it seems effective Lean thinking would lead to lower infections rates.

That said, I think we have a lot to learn from complementary methods like “just culture,” aviation safety practices, and other methodologies.

Lean isn’t a magic silver bullet, but I still don’t know if we’ve seen the ultimate in Lean systems in healthcare yet. Even Virginia Mason doesn’t measure up in some ways.

I don’t know…

“Mandatory” is a key theme of Studer’s approach and it’s had some success. Yet, like Lean and other philosophies, it’s stickiness is still a function of many cultural and organizational factors.

I’m all about enabling the right behavior and outcomes (Influencer Model is a great approach). Technolology has also become a powerful tool to drive clinical quality and patient experience (RFID tags in surgical sponges, Beacon for wayfinding and asset tracking, Continuous Patient Monitoring/Rothman Index for earlier identification of patient deteriation, etc). But our systems are always going to be the result of the things we tolerate. Do we tolerate a clinician not handwashing in and out of rooms? Do we tolerate less than 100% time-out compliance? Do we tolerate unsanitary plumbing issues? If so, we’re accepting Sepsis, RFO’s, and HAC’s by proxy.

And I use Definitive for Hospital performance benchmarking (mostly reported via CMS but it also has some other additional performance info).

Mark, your passion for safety really comes through and is inspiring! I’ll limit my comments to share a timely connection to the recent media reports of poor care and unsafe facilities in the VA Healthcare system (Manchester, NH most recently, they also had flies in their ORs). It hits close to home for me as I was their Lean Program Manager for almost three years before the access problems hit the fan in 2014. Yes they have serious problems, but the media in this case missed the enormous opportunity to say this is not unique to VA healthcare, and challenge the presumption of pundits and politicians who have responded by calling for elimination of the VA system in favor of private healthcare…because it’s supposedly so much better (except for this one system in DC, of course). I’ve worked in 3 private systems, and can say without hesitation there isn’t a problem in the VA system that I haven’t seen in private healthcare. And I agree with you and others here, it’s a leadership issue.

Thanks for the comment, Tom.

Here’s one news story about the ongoing situation in Manchester.

I think USA Today also missed an opportunity to point out the problems at this hospital aren’t necessarily unique other. We have safety problems everywhere… and leadership issues, too.

There are safety and access problems in other countries too. This isn’t a uniquely American problem, either…

Sadly, passion for patient safety doesn’t always lead to much progress. Hospitals reach out to talk about Lean and efficiency, cost, and patient flow. Not to sound whiny, but nobody reaches out to ask for help with patient safety and quality.

As it said in this blog post:

“..you have to persuade [your audience] to let go of their status quo. That may not be endearing to them.”

Comments are closed.