As I've mentioned before here on the blog, I played drums for four years in the Northwestern University Marching Band (NUMB) from 1991 to 1995 (graduating just before the amazing Rose Bowl season).

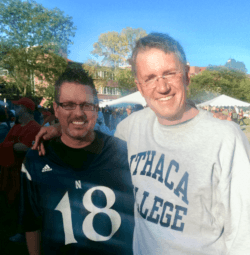

The director of NUMB at the time was Dr. Stephen G. Peterson. He later became the director of bands at Ithaca College and we crossed paths at a Northwestern vs. Syracuse football game maybe about 8 years ago in upstate New York, as pictured above. He's now the director of bands at the University of Illinois, a famed, historic, and influential band program.

I was an industrial engineering student, but had always been a pretty dedicated musician (or you could make the joke that drummers aren't musicians, ha ha). I learned so much, during those four years, about leadership and excellence and much of it came from the marching band experience. To me, Dr. Peterson was a fantastic leader for many reasons, one of which was his commitment to helping us be the best we could be.

That's the red arrow pointing at me, a photo from about 1993. Yeah, I wasn't bending my knees as much as I should have been there (we didn't normally march or stand crouched down like that).

Recently, I was happy to find a podcast discussion with Dr. Peterson, from the “Bandmasters” podcast (which is, of course, geared toward band directors and students who want to follow that career path).

Here is a link to the full podcast episode:

There were two parts of the discussion that were particularly compelling to me about the type of work we do with Lean and Continuous Improvement.

Here are his comments below (with my thoughts in bold italics).

Hear Dr. Peterson's remarks and Mark's comments (subscribe to Lean Blog Audio)

Unimportant Details?

“Dr. Stephen G. Peterson: Just another really weird example that I use with young teachers… I have been going into positions where, in my early teaching, there was a strong marching band tradition.

They would do things a certain way. Even simple things like how you call yourself to attention (see an example of this). Things that are completely unimportant — really unimportant — but important to those students because it makes them who they are.

To go in and completely change things like that for what might be a good reason but really isn't is silly. It puts you in a bad light.

Go in and learn. Figure it out and make your decisions and your choices wisely and slowly based on what you learn over a period of time.”

Do Lean practitioners face similar challenges when it comes to the existing practices of an organization? What if your approach flies in the face of the existing “Lean culture,” if one has already been starting to form?

Do unimportant details, like the exact format of an A3 template or the exact words on a Kaizen card really matter that much? What if you came into an organization and tried to change that or said that a huddle board had to look a certain way and only that way?

Would that “put you in a bad light,” as Dr. Peterson says? Would that make your efforts to engage people more challenging than they need to be?

A musical interlude from 1996, when Dr. Peterson took NUMB to the Rose Bowl:

Better and Good

Dr. Peterson continues:

Dr. Peterson: “I'll get off of my soapbox here for a second and say we have this epidemic amongst, not just teachers, but you name a profession — any profession in the world — where we just tend to settle. We tend to settle for something.”

Is the same true sometimes in healthcare, when we hear leaders talking about, for example, the way certain hospital-acquired infections or errors are just inevitable? How many leaders settle for mediocre performance instead of aiming for zero, as leaders like Paul O'Neill have done?

“A couple of things that really get my back up are when conductors say something like, “That's good enough.” In music, it's never good enough. There's always a place we could be better. Always, always, always, it's never good enough. We're always chasing that by training.”

That sounds like the practice of Kaizen, or continuous improvement. We're always chasing a better way (or we should be). Toyota talks about the continuous pursuit of perfection. We did the same thing under Dr. Peterson in the marching band, even if perfection was unlikely.

“[Perfection] just doesn't happen. Sure there's no such thing as a perfect performance, at least not in my experience. We are always looking for that. The other term that I think will bring us down someday is when band directors say something is good when it just isn't.

“That's good.” “That sounds good.” “No, it doesn't.”

Interviewer: [laughs]

Dr. Peterson: It sounds better. Better is the best word that ever came along for a music teacher because I can acknowledge improvement. I can acknowledge that things are getting better without calling something good.

Healthcare and other industries talk a lot about “best practices.” How do we know something is as good as it can be? Should we talk about “better practices” and leave it at that? In our own improvement efforts, many small incremental improvements might make a process or system and its performance “better” but it might not be “good.”

Of course, Dr. Peterson has his own specific definition of “good” and it sounds like he uses it consistently… and his students are probably calibrated to that. I'm sure some leaders out there call everything “good” even if it isn't, and maybe that confuses people or sets the bar too low?

Do leaders need to make sure they acknowledge improvement without somehow stifling further improvement by making it seem like things are perfect?

I'm not going to label something as good until it sounds pretty darn good. The world's full of us lowering the bar in the band world, you name it, computer world, it doesn't matter. We just settle. “That's good.” “No, listen. Did you just hear that phrase? That phrase isn't good because of this, this, this, and this. It's still happening. It's still not right. Let's fix this thing.”

Using my rehearsals, when I'll say, “That sounds good,” it's always very quiet because everybody knows there's going to be another half to that statement, like, “That's really good, but now oboes. We need to…”

Or, “That's really good, but did you hear that…” whatever. There's always something else. Those directors who are really successful are the ones who hear that first of all, and are good communicators — there's a lot of other things — and are able to isolate and find the problems, and are not afraid to go after them.

Too many band directors are willing to say, “Your flute, that's really out of tune. You've got to fix that,” and leave it at that. What good is that? That doesn't help anybody. No one's going to get any better.

I think Dr. Peterson is pointing out the difference between criticizing and coaching. Is it enough for a manager or executive to say something like, “Patient falls, that's too many. You've got to fix that?” Will they get better as a result of the manager just pointing out a problem? Probably not. Dr. W. Edwards Deming would have asked, “By what method [will you improve]?” You need more than a target. Leaders and Lean coaches can be more helpful than just pointing out the fault.

To have a culture of continuous improvement, do we need leaders (not just Lean specialists) and staff who are better at isolating and finding problems… and not being afraid to “go after them?” We can “learn to see” problems through practice, but we can't just tell people to not be scared… we have to make change small (as discussed in this podcast).

Unless maybe at my level, maybe here with the Illinois Wind Symphony. When I tell a flutist, “That's out of tune,” I've got some pretty good players. They know what to do to fix that. If I go back and I say — I'll do this often — “We need to do letter F again so the flute's going to have another chance to listen to each other.”

We'll do it again, and they'll make it better. If not, I'm going to go back and I'm going to help them even more, isolate wherever the issue is.

In most high schools, you got to help. What I believe is most directors either have given up and they just, “That's good enough,” or they really, honest-to-God don't hear themselves. My advice to those folks is, if you really do want to hear it, then you got to do a few things.

You got to work a little harder. You got to record your rehearsals more often until the point comes when you feel confident that you're actually hearing things. It took me a long time.

Have some healthcare leaders given up? Do they realize patients are falling, and that it's bad, but they think it can't be better? Maybe they think they've tried to improve, but they were just putting the data up and making people feel bad. A leader has to do more… not just work harder, learning how to find new ways of analyzing, improving, and leading.

Part of that is being vulnerable in front of your students and saying, “Let's do that again because I'm not exactly sure,” or, “Can I just hear the oboes here because I'm not sure who's sharp, who's flat. Let's see if we can figure this out.”

To me, that sort of vulnerability is like humility (an important leadership concept for Toyota and Lean practitioners). If an employee comes to a manager with a problem, they often expect the manager to have an answer or a solution. In Kaizen coaching, we talk about leaders not giving answers but instead challenging and coaching employees to come up with potential solutions that they can test. Managers might not have the best answer… or they might not have any. It makes a manager (and especially a senior executive) vulnerable to say “I don't know,” but that's often what they need to do.

The people who are willing to stop and go back and get to the root of the problem, both for the students' sake, to teach them, and especially for their own sake, to teach themselves how to get better at that, they are the ones who're going to succeed.

“Getting to the root of the problem” is, of course, something we do in the Lean methodology. That allows us to truly get better instead of firefighting all of the time.

I did not mind when I was very young, when I was first teaching, putting it out there in front of my students, and acknowledging that I was going to make mistakes too. Honest-to-God, I think that's one of the best things I ever did.

That's the same advice I give to leaders in the context of Lean or Kaizen. If you make a mistake (and you will, because you're human), it's better to own up to it and admit it. If an employee comes to you with an idea and you shoot them a look that says, “That's dumb,” then admit it and apologize for it (and hopefully you or a coach notice that you did that). Leaders set an important tone for an organization, when they admit they aren't perfect that, perhaps ironically, helps us all get closer to perfection over time as a team.

I didn't think about it that way, I was wired that way. Some of us are not wired that way at all. Some of us have so much armor up around us that we can't possibly allow our students to think that we're not perfect. That's unfortunate for those people.”

It's unfortunate for those leaders in healthcare (or startups, factories, or any setting) who think that way.

What are your thoughts on Dr. Peterson's comments? Were any of you also fortunate to learn lessons from your time in the marching band?

What do you think? Please scroll down (or click) to post a comment. Or please share the post with your thoughts on LinkedIn – and follow me or connect with me there.

Did you like this post? Make sure you don't miss a post or podcast — Subscribe to get notified about posts via email daily or weekly.

Check out my latest book, The Mistakes That Make Us: Cultivating a Culture of Learning and Innovation:

What I like about this story, and what I find a lot of leaders get confused on, is the value and importance of real time feedback. Having a director/leader with a clear view of the ideal state in their mind is so critical, and that they can communicate it clearly and consistently equally so – and just as important is the ability to get real time feedback as the process is running/music is playing from the customer. Dr. Petersen was doing that in the band context – the band plays, he hears it, he does it quick comparison to what he expects, he calls out exceptions, problem solves, and they do it again, and he hears the results again.

Too often, I find that one of those three pieces are missing – the leader doesn’t have a clear view, or they can’t communicate, or the feedback isn’t real time or consistent. Some process lend themselves to that – a band, an artist, a production line with andon – leaders get the feedback immediately. Other processes, like a 24 month development cycle don’t give that feedback. Hospital borne infections from a medical error may take hours, days, or weeks/months to show up. Part of my work is around how to get that feedback faster, to the right leaders, so they can take action right away. I wish everything was as clear as a missed note in an orchestra!

Thanks for your comment, David.

I agree that anything we can do to speed up cycles of learning is helpful, whether in the “Lean Startup” sense or Kaizen/PDSA improvement in any setting.

When can we do small tests of change or pilots to test an idea, instead of waiting for the end of a 24-month cycle? I’m fascinated by concepts and methods from the Lean Startup methodology that get customer feedback and input sooner rather than later.

Can we do the same with improvement ideas in healthcare? Instead of huge projects and committees, can we get faster, smaller-scale improvement that then scales?

My high school band (Mark knows–down the road from his in Livonia) was very competitive and very successful–and had a strong culture of never settling. My college band was… different. In high school we were taught to come to attention by inhaling–filling the lungs and raising our posture on that breath of air. The air and the position of attention were synonymous. In college, they shouted “1-2”–which was just fundamentally wrong to me. (I need air to come to attention, not to shout it out!) But you go along. Then one summer, our band director read a book about—true story–Total Quality Management. He decided to change our “1-2” shout to “T-Q!” to remind us all that we needed to have “total quality” in all that we did.

Needless to say, the whole band thought it was a complete joke.

I waited the prerequisite month or two for the excitement about TQ to wear off, and used my role as a drill instructor to ask the director what he thought about changing the call to “V-U”–the initials of the university.

It stuck. They still shout “V-U” to this day. Change… with a reason.

Of course, they still don’t look as good at attention as my high school band. ;-)

What an epic story, Andy. I had no idea that a band leader would get into TQM.

That should have been a chapter in the book “Why TQM Fails.” ;-)

A former boss of mine was fond of saying “Best is the enemy of better” – loved that line – I believe he heard in a seminar – strikes me that “good” can also be that enemy.

Fun to read this. I was in the Phoenix Central High band the last year of Dr Peterson’s student teaching there, and first two years of his taking over as Director. We were an award winning marching band under his direction. Interesting to hear his perspective on his early years. We certainly strove to please him! And he did expect us to excel, which we did.