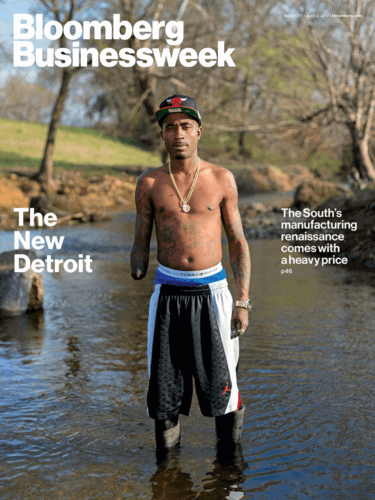

A few of you sent me this article… and you were correct to think I would be interested:

“Inside Alabama's Auto Jobs Boom: Cheap Wages, Little Training, Crushed Limbs

The South's manufacturing renaissance comes with a heavy price.“

The cover photo is of a man, Reco Alan, who lost his arm in a press that plant management allegedly knew was dangerous.

From the article, as a summary of the horror stories from auto plants in the southern United States:

“The files read like Upton Sinclair, or even Dickens.”

I remember reading Sinclair's book The Jungle in college and I was appalled that safety could be so abysmal in the meat-packing plants of the day. The book was published in 1906.

We've heard horror stories about poor safety and bad working conditions from factories in Asia in recent years, but one would think things would be better in the United States where you have, in theory, OSHA and other regulatory agencies looking out for workers.

But I guess that hasn't been the case in the new (and mainly non-union) factories of the south.

Hear Mark read this post — subscribe to Lean Blog Audio

The article opens with the story of Regina Elsea who was killed when she was impaled on a robot that wasn't properly “locked out.” She worked at a factory run by Ajin USA in Cusseta, Alabama. They are a South Korean supplier to Hyundai and Kia.

This accident should have never happened. It was totally preventable.

Hell, even in my horrible GM plant 22 years ago, they had a proper “lock out / tag out” program. I even had a lock with my name and photo on it that was supposed to be used to protect me if I had to go inside equipment.

It seems like Ajin didn't take proper precautions, didn't train workers, and allowed pressure over production numbers to make safety a low priority.

From the article:

“On June 18, Elsea was working the day shift when a computer flashed “Stud Fault” on Robot 23. Bolts often got stuck in that machine, which mounted pillars for sideview mirrors onto dashboard frames. Elsea was at the adjacent workstation when the assembly line stopped. Her team called maintenance to clear the fault, but no one showed up.

A video obtained by the Occupational Safety and Health Administration shows Elsea and three co-workers waiting impatiently. The team had a quota of 420 dashboard frames per shift but seldom made more than 350, says Amber Meadows, 23, who worked beside Elsea on the line. “We were always trying to make our numbers so we could go home,” Meadows says. “Everybody was always tired.””

They were probably tired over the pressure to hit a number (420) that didn't seem possible if they “seldom” made more than 350.

“After Elsea's death, Ajin issued a statement saying all employees were being retrained in safety procedures.”

Ah, retraining as a countermeasure. Hospitals are guilty of that approach too, after a patient safety incident. It sounds like they are blaming workers for not being properly trained, which is silly. I never hear management asking why initial training wasn't done or why it was ineffective to begin with.

I'm not blaming the auto workers… I'm blaming management for (most likely) creating a high-pressure “make the numbers” environment (one that I remember from GM and other manufacturers I worked for). I'd also blame management for not creating a culture of safety like Paul O'Neill did at Alcoa. I'd also blame them for not working with workers to improve the system in ways that would have made it possible to hit production goals.

She entered the robot enclosure without ensuring that it was “locked out” and powered off:

“After several minutes, Elsea grabbed a tool–on the video it looks like a screwdriver–and entered the screened-off area around the robot to clear the fault herself. Whatever she did to Robot 23, it surged back to life, crushing Elsea against a steel dashboard frame and impaling her upper body with a pair of welding tips. A co-worker hit the line's emergency shut-off. Elsea was trapped in the machine–hunched over, eyes open, conscious but speechless.”

The story continues where, sadly, nobody knew what to do after the accident occurred. She later died at a hospital.

Again, don't blame the worker… blame the company:

“Ajin, according to OSHA, had never given the workers their own safety locks and training on how to use them, as required by federal law. Ajin is contesting that finding.”

The article does mention a Toyota supplier being fined for safety problems, so it's not fair to paint this as a South Korean business problem.

It's disappointing to hear of such problems from any auto maker in this day and age. It's been almost 20 years now since I quit GM to go to grad school. It seems that most auto factories had closed the gap in quality and productivity with Toyota… and I would have hoped they would have gotten safer.

Does Toyota Do Better?

When you visit the Toyota plant in San Antonio, you see evidence of a focus on safety (or what appears to be such a focus).

Even a display robot in the visitor center has visual instructions posted about proper lockout/tagout procedures, as I shared here.

What About Hospitals?

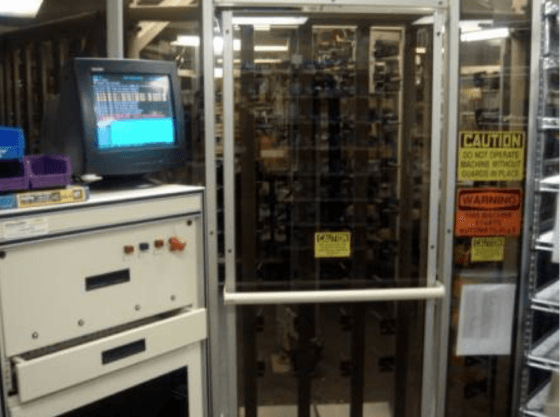

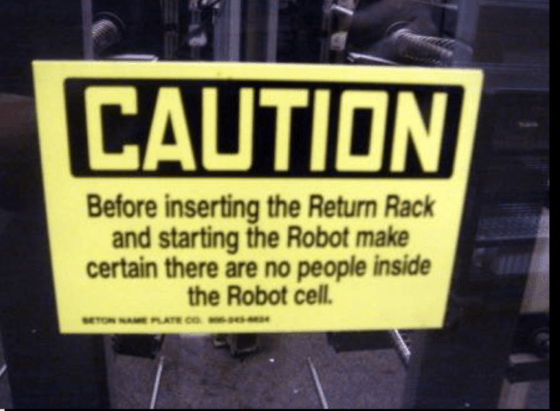

I've seen robots in enclosures in hospitals that didn't have such protection processes in place, such as this pharmacy robot that relied on a sign… a weak form of protection compared to a proper lockout/tagout process.

A sign saying “make certain there are no people inside” is not good protection.

I remember asking about a “lockout/tagout” process and I don't remember the pharmacy leader knowing what that was. Maybe I should have reported them to OSHA.

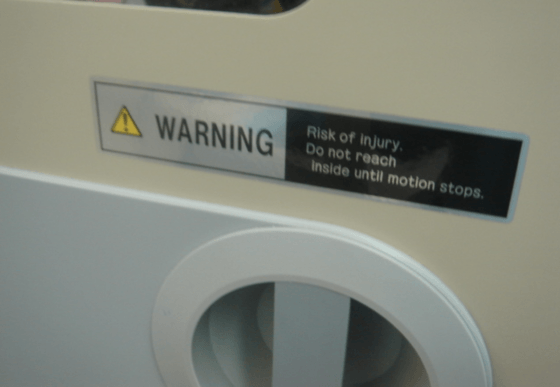

I also have a photo of this pharmacy automation and its warning sign:

As I've discussed in my “Warning: Signs!” keynote talk and my BeMoreCareful.com website, signs aren't a good substitute for error proofing.

That pharmacy equipment should be impossible to open if it's moving inside… that would be much better. It should be impossible to start it when somebody is reaching inside. That should have been possible to engineer.

So, factories don't have a monopoly on poor safety practices. Nobody was killed or injured in these pharmacy robots when I was around… but that might mean they were lucky. They both seemed like an injury waiting to happen.

How Does This Happen?

The Bloomberg article points out many management and culture problems that can lead to safety problems and harm, including:

- Pressure to hit unreasonable production targets

- “The focus of this plant is production at all costs.”

- Employees working long hours and lots of overtime

- Not receiving proper training

- Carmakers “squeezing suppliers too hard” on price, delivery performance, or financial targets

- Maintenance managers “being too busy” to write up proper lockout procedures

- Ignoring known safety risks and near misses (“Upper management knew all that. They just looked the other way.”)

- Not respecting and listening to employees, as one said, “They don't pay you no mind; they just want you to work.”

Are hospitals ever guilty of any of those bad habits or mindsets? Sometimes. And that's sad too.

I guess there's a reason that Toyota, while not perfect, feels the need to talk about “respect for people,” which includes a focus on safety (not just in their own plants, but for their suppliers).

As ThedaCare's CEO Dr. Dean Gruner says, if you can't do something safely, you shouldn't be doing it at all:

Why is it so hard to get factories or hospitals to focus on safety as a primary goal, beyond lip service?

What do you think?

Please scroll down (or click) to post a comment. Connect with me on LinkedIn.

Let’s build a culture of continuous improvement and psychological safety—together. If you're a leader aiming for lasting change (not just more projects), I help organizations:

- Engage people at all levels in sustainable improvement

- Shift from fear of mistakes to learning from them

- Apply Lean thinking in practical, people-centered ways

Interested in coaching or a keynote talk? Let’s talk.

Join me for a Lean Healthcare Accelerator Trip to Japan! Learn More