Continuing my series of blog posts about my July trip to China, today's post is about my first significant walk through a hospital during the trip.

My group had a chance to visit the First Affiliated Hospital of Chongqing Medical University.

It's, of course, located in the city of Chongqing, which we reached via a flight from Shanghai. Chongqing is a fast-growing city with an urban population of about 18 million, located in the western part of the country.

The view from our hotel showed clusters of the lookalike high-rises I mentioned in my first post (as seen in other cities and in the middle of nowhere). You can also see one of the major bridges across the river:

Out the other direction, I would see what looked like a very traditional shrine… next to a huge pit that will probably be another high rise:

The Hospital & Medical School

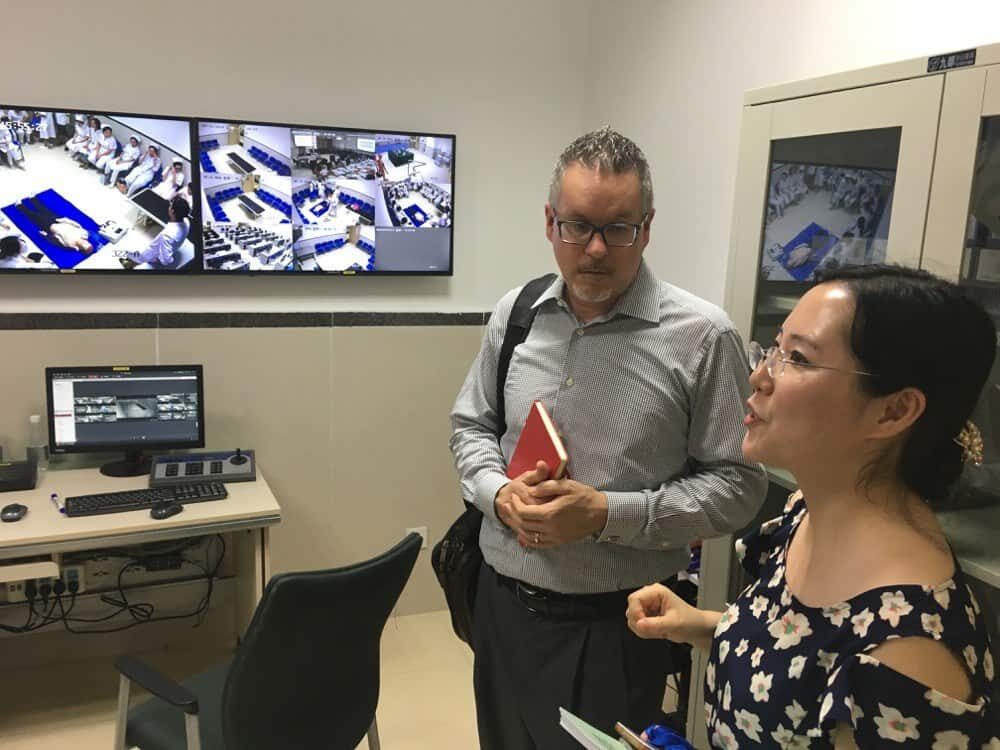

The newest hospital tower was built in 2013, but the medical school and the original hospital date back to 1957. The new tower (19 stories) was very modern and impressive, as were the modern training, simulation, and telemedicine spaces, as seen below:

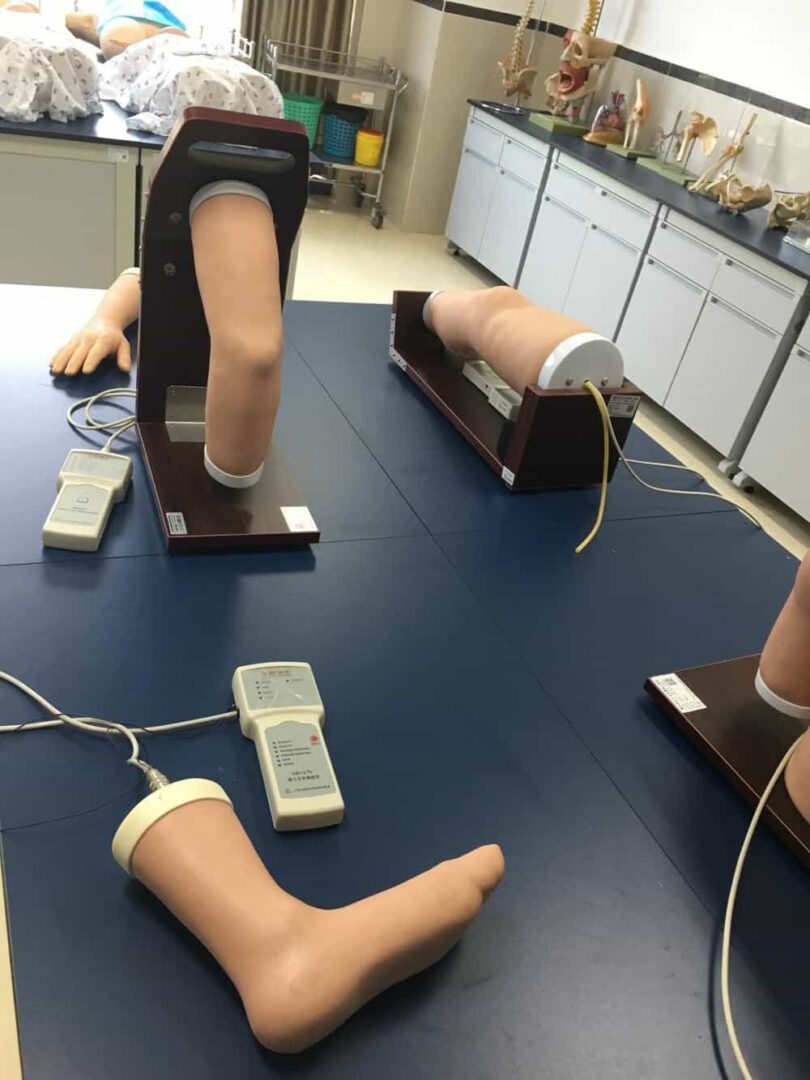

And there were training feet and many simulated body parts (of ALL body parts, in different areas):

Some simulators allowed students to practice doing sutures and searching for lumps beneath the skin surface.

Telemedicine is helpful here because they have a network of 95 hospitals across the western part of the country, including many rural areas, as shown in the map:

They offer remote radiology, pathology, and cardiac diagnosis through these rooms:

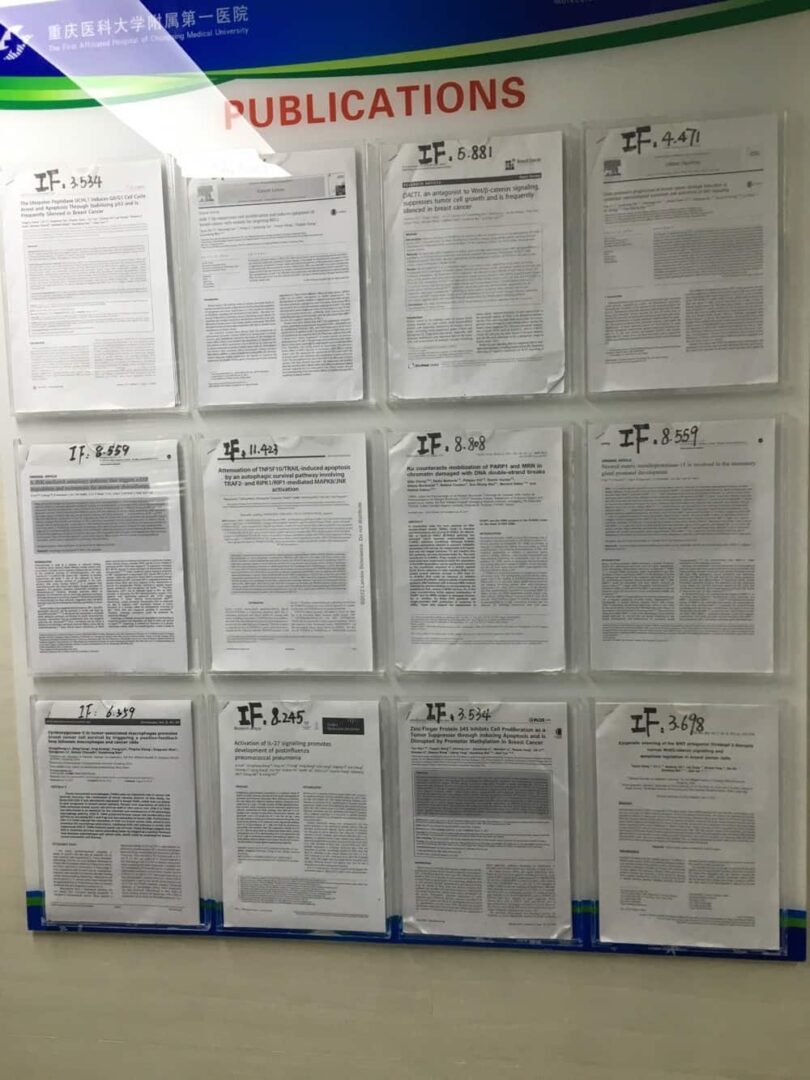

As we walked through a molecular oncology lab, we saw many publications on the wall, and one of our Chinese hosts commented, with a chuckle, that they must “publish or perish,” which seems like the academic environment in other countries. They were proud of their research and publishing:

A Modern Facility Doesn't Mean Lean Thinking Follows

We had a chance to visit their clinical laboratory. It was a new, beautiful space with all of the latest equipment. Unfortunately, it was the typical modern non-Lean laboratory where the flow is disconnected with different rooms.

For example, “Specimen Reception” was its own room, instead of being incorporated into the analytical testing flow.

There was a specimen sorting machine that spends a lot of time automatically doing, in a more time-consuming and complex way, what a human could do — putting different colored specimen tubes into different racks. That's a classic example of automating the wrong type of work. In a Lean lab, those specimens would flow almost immediately to the analyzers without spending time being gathered and batched.

They had a modern “flow track,” which is (as I've seen labs across North America and Europe) a fancy way of automating the waste of transportation. In this lab, the “core lab” high-volume analyzers for chemistry and hematology were a very long distance from the specimen receiving area. A Lean lab would have a more compact layout and wouldn't need the track necessarily (some Lean labs have taken out the tracks because a Lean layout leads to faster turnaround times).

The hospital also has a separate “emergency lab” near the emergency department. This is a common non-Lean reaction to the main lab returning lab results very slowly. When you reduce the batches and delays and tighten up the core lab layout, a good Lean lab can outperform the typical “stat lab” in an emergency department — faster clinical lab results and a lower cost.

I don't mean to be critical of our Chinese hosts. My point is that, even with the talk of Lean culture and improvement, there are still many opportunities to incorporate Lean thinking into the design of spaces. The same is still true in many American hospitals.

Outpatient Care

When we got to the outpatient clinic, it was in the late afternoon, so it was far from the busiest time of day. They have 10,000 outpatient visits per day at the main hospital for 17 specialties.

You can see some of the technology that's used for different purposes, such as signs that tell patients which room to go to when it's their turn (up high in the photo):

And the kiosk, which you can see in the photo above, is also shown below. It's used for patients to make appointments, check in, pay for services, etc. I believe a kiosk is just an option, as people can also stand in a queue to pay (labeled “Registration Fee Place”), and they can book appointments using WeChat on their mobile phones (or by calling the old-fashioned way).

Our young translator giggled a bit when I mentioned American hospitals and doctors using fax machines :-)

The outpatient center takes up five floors of the facility. Only about 25% make appointments and the rest walk in and wait.

The hospital is enormous, with 3200 beds, 120,000 discharges, and 80,000 surgeries per year.

The CEO is a surgeon and I had a chance to talk with her the next morning when we had some conference presentation time, as we had in the other cities.

The City and Our Chongqing Conference

We learned, the next during a lunch discussion at our conference in Chongqing, that the hospital is doing “quality circle” improvement projects (as I saw in Japan), with everybody (or most everybody) being involved in one.

But, before the conference day, we had a traditional “hot pot” dinner, a speciality of the area. It's sort of like cooking food in a large fondue pot with regular broth and a VERY spicy broth.

The city's lights were beautiful, as we saw that evening after dinner across the river from our hotel.

The next day, it was 95 degrees and we all decided to go without suit coats. We had stopped wearing ties as an initial countermeasure to the heat in previous cities. None of the Chinese physicians, leaders, or conference attendees were wearing ties, unlike American hospitals :-)

At the conference, I've never had a podium with such beautiful flowers:

Here's my name card, with a Starbucks that they brought for me:

As I had mentioned in my first post, the hospital CEO sat in the front, had already read my book, and asked the first question:

She asked about practical things that leaders can do to help in a Lean transformation.

I also had a nice chat with Allan, who plans on studying healthcare policy at MIT (and he asked me to sign his book):

During lunch, we had a great discussion with some physicians and the head nurse.

One person brought up the topic of incentives, asking how we can get people to want to improve. Improvement has traditionally been, for them, something that managers “tell us we have to do” (sounds familiar).

A physician brought up the power of intrinsic motivation, which is what I often do.

“We should want to improve.”

We also discussed “fire fighting” (this was difficult for our translator), and they described situations where they “solve” the same problem “over and over.”

Again, that sounds very familiar.

I want to thank my Chinese hosts for a very interesting visit to the hospital.

What do you think? Please scroll down (or click) to post a comment. Or please share the post with your thoughts on LinkedIn – and follow me or connect with me there.

Did you like this post? Make sure you don't miss a post or podcast — Subscribe to get notified about posts via email daily or weekly.

Check out my latest book, The Mistakes That Make Us: Cultivating a Culture of Learning and Innovation:

With the huge volumes they have and no way to stabilize it .Wondering if you asked what the error rate in that lab was using technology.I am thinking that injecting the human element was a variable they chose not to have in the system.

It is an amazing place .Is there anything of that size in America

The largest hospital in the U.S. is about 2300 beds.

See this list.

The old approach in Chinese manufacturing was to “throw people at the problem” since labor was so cheap. I bet the new hospital wanted to have the “latest and greatest” and the lab equipment vendors convinced them that a “state of the art” lab would have automation like this (the vendor makes more money selling automation instead of selling a Lean process).

When I worked for J&J, our lab group helped people create a Lean lab that didn’t require automation.

If somebody doesn’t have the Lean mindset, they’ll be wowed by fancy technology, just like Roger Smith was enamored with automation at GM.

I did not ask what the error rate was.