As I wrote about last month, I love newspapers, so I felt like I fit into the culture last week when I spent five days of my vacation in London, a city I really love. People in England seem to be avid readers, based on the number of newspapers on sale and the number of ads in the Tube stations for various books, including many ads for Dr. Atul Gawande's latest book Being Mortal. Newspapers seem important enough to the culture that the competing BBC and Sky News channels on television each have a full program each evening that previews the next day's papers.

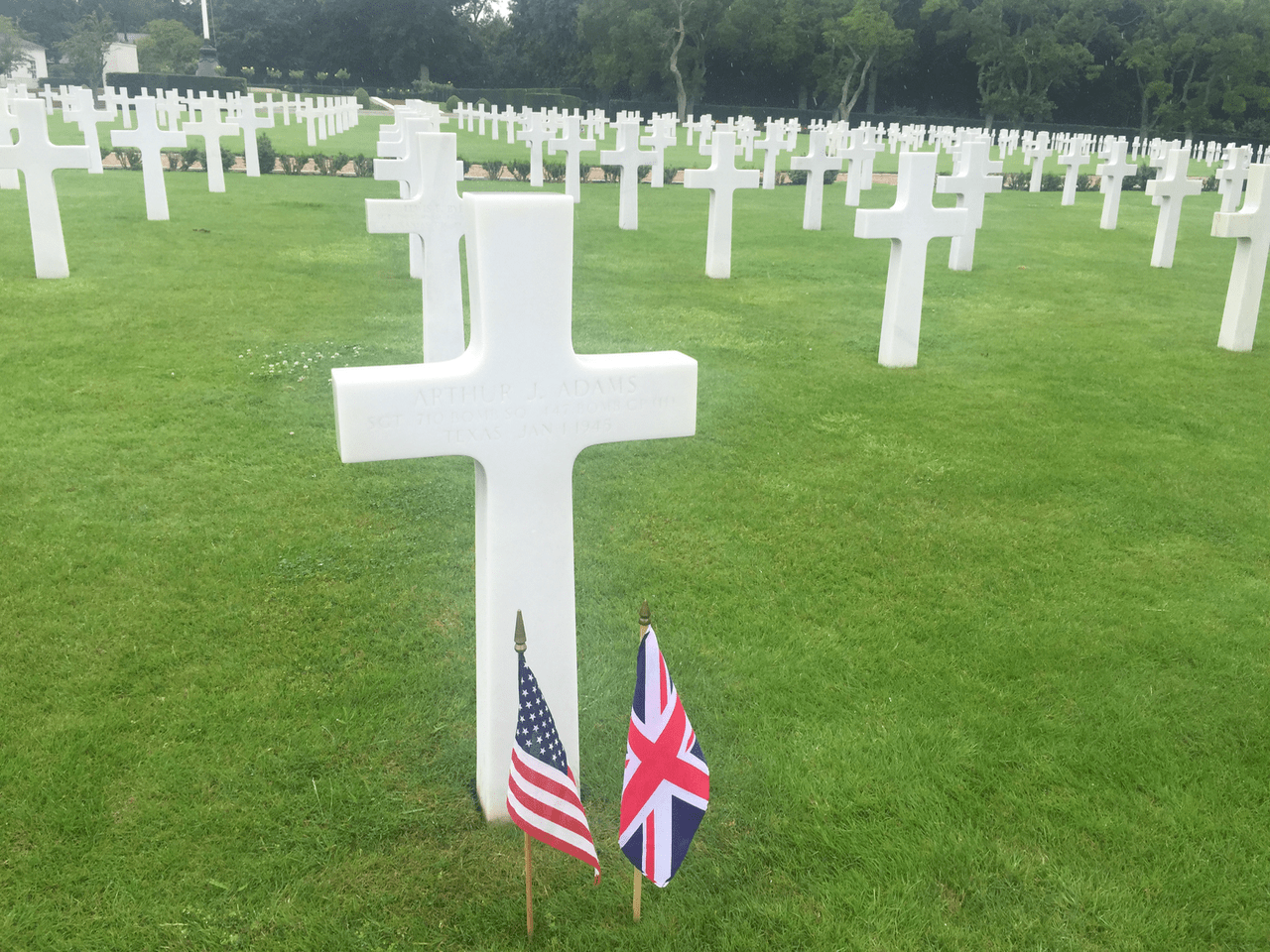

So, I make it part of my routine to read a few newspapers each day in London, over breakfast or while on a long train ride, such as our trip to Cambridge to visit the American Cemetery, which has some special meaning to my father-in-law.

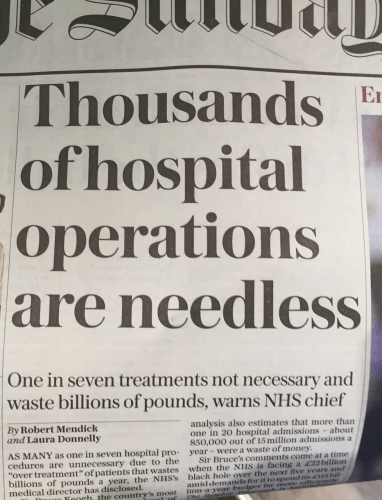

One morning, I picked up the Sunday Telegraph and had a bit of breakfast while my family slept in. I read the main headline from the paper:

Here is the article online:

One in seven treatments not necessary, warns NHS chief

The most senior doctor in England has described the level of NHS waste as ‘profligate' as officials admit £1.8 billion spent on unnecessary operations and medicines

Unnecessary care is a problem in the United States, as pointed out by people like Dr. Gawande, the Institute of Medicine, and others. Unnecessary surgeries, duplicative testing, and the like are often blamed on a lack of coordination or “defensive medicine” and some point to greed in a fee-for-service reimbursement model, where surgeons and hospitals get paid for what might be deemed “unnecessary.” I've always thought the problem was far more complicated than simple greed.

Global problems: One in seven treatments not necessary, warns NHS chief Share on XIn the NHS, surgeons are paid a salary, which you'd think would reduce any financial incentive to do work that doesn't add value to a patient's life. As this article says:

“NHS contracts pay them for their time, regardless of the numbers of patients they treat. They know that working slowly means that more patients will be sent to nearby private hospitals, which employ those same surgeons to undertake operations on a case-by-case basis.”

Unlike Canada, there is a separate private healthcare track that exists outside of the government hospitals. But, I believe this analysis of unnecessary surgeries is pointed at the NHS, not private surgery centers.

From the Telegraph:

Sir Bruce Keogh, a former cardiac surgeon, said that “a substantial proportion” of spending in the NHS was wasted on ineffective care, and he estimated that ten to 15 per cent of medical and surgical treatments should not have been carried out on patients.

His officials at NHS England said unnecessary operations and medication were now costing the NHS up to £1.8 billion a year. That would be enough to pay the wages of all ambulance staff for three years.

Needless operations can also place patients in danger, putting them at “high risk of adverse events” for surgery they didn't need.

The reasons for overuse of treatment include a lowering of thresholds for interventions in such conditions as cataracts, the most common operation in the NHS; people being offered expensive treatments when cheaper alternatives are available; and misdiagnoses of illnesses

Listen to Mark read the post (learn more):

It's not just surgery, but also inpatient admissions:

The NHS England analysis also estimates that more than one-in-20 hospital admissions – about 850,000 out of 15 million admissions a year – were a waste of money.

Even without the context of huge budget pressures, I agree that we should all look for waste and that there's no shame in admitting a problem – that's the first step in solving any problem.

“We also have a massive duty to look into all our organisations and to look into the waste. The waste is profligate in our system. I don't think we should be ashamed of pointing that out and certainly we shouldn't be ashamed of dealing with it.”

Instead of any “greed” factor, there seems to be the “other peoples' money problem” at work (which is also part of the complexity of the American healthcare waste problem):

Sir Bruce told a conference of senior doctors and managers: “Historically, doctors and to a lesser extent nurses have felt that the money is someone else's problem … I think we need to collectively challenge that because we are in a tax-funded system which does as well as our economy does and when the economy sneezes the NHS catches a cold – and at the moment the money is relatively stagnant for the foreseeable future.”

Inside that same paper was a big headline about patient safety and harm:

The article:

Medical blunders cost NHS billions

An analysis by The Telegraph shows 20 hospital trusts have paid out £1.1 billion for medical blunders in just five years. While below we tell the tragic story of a mother left severely brain damaged after giving birth to her daughter

Again, a similar problem to what we face in the United States (and every other developed country).

The article highlights not just the harm to patients, but the legal fees and settlements that are paid out.

This number was shocking to me:

The NHS LA estimates the money needed to settle all medical negligence claims is between £25bn and £30 billion – almost a third of the £115bn a year NHS budget in England. The huge sum is the amount the NHS would have to pay if all negligence cases, including ones lawyers have still to bring, had to be paid out at once.

One third, 33%, of their national healthcare spending on settlements from negligence cases? Good gracious.

Some seem to blame the lawyers, but as I've said about “tort reform” efforts in Texas and the rest of the U.S., the best tort reform is to reduce the number of torts. We reduce the number of torts by improving systems and reducing harm, not just by apologizing and admitting fault sooner.

The best tort reform is to reduce the number of torts. Share on XI agree with this statement:

“If the NHS wants to save money it should focus on reducing the number of medical errors so there are fewer innocent victims needing our help,” said Lisa Jordan, Partner and Head of Medical Negligence at Irwin Mitchell…

The official National Health Service (NHS) estimate of British patient deaths or serious injuries due to medical error is 11,000 cases a year (Parliament report, 2008).

In 2014, the NHS says the number is 12,500 British deaths per year (Nursing Times).

At the higher number, that puts the per capita rate at 12,500/64,100,000 or 0.000195. If 200,000 Americans die each year due to medical error, then our per capita rate is 0.000627 or about three times higher. Does that mean American healthcare is three times more dangerous, or do we have a data and reporting problem all around?

The next day, I saw this headline about waiting times:

The article:

That seems more like a Canada problem than an American problem, but in the U.S., if you don't have affordable healthcare, your “wait” might be no care at all.

From the start of the article:

Almost 3.4million patients are languishing on NHS waiting lists – the highest number in seven years.

They include more than 6,100 forced to wait at least a year for operations or treatment. In the worst examples the delay has been nearly three years.

The numbers are the highest since January 2008 and show the extent to which hospitals are struggling to meet the needs of the growing, ageing population.

Experts said the waits of weeks or months were extremely distressing for patients, some of whom are in considerable pain.

Read more: http://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-3158591/Hospital-waiting-lists-seven-year-high-3-4m-need-treatment-6-000-forced-wait-year-operations.html#ixzz3g3XvgDUL

Follow us: @MailOnline on Twitter | DailyMail on Facebook

The article talks about targets. Targets alone don't fix anything and they can cause a lot of dysfunction (see the VA scandal from the U.S.).

How can the NHS reduce waiting times without throwing money at the problem? Are they using Lean to increase capacity and throughput in a way that also improves quality? The recipe is “reduce waste.”

There's usually the need to improve three things in any industry:

- Quality

- Cost

- Speed

Traditionally, people would say you can get it “good and cheap but not fast” or some combination of just two of those things. Lean healthcare helps show that we can improve in all three dimensions simultaneously. We need “better, faster, cheaper” healthcare around the world and we need to go about it right way – improving systems rather than just cutting costs in a way that slows care or hurts quality.

Big challenges, global challenges.

Please scroll down (or click) to post a comment. Connect with me on LinkedIn.

Let’s build a culture of continuous improvement and psychological safety—together. If you're a leader aiming for lasting change (not just more projects), I help organizations:

- Engage people at all levels in sustainable improvement

- Shift from fear of mistakes to learning from them

- Apply Lean thinking in practical, people-centered ways

Interested in coaching or a keynote talk? Let’s talk.

Join me for a Lean Healthcare Accelerator Trip to Japan! Learn More

Mark: your audio blog really resonated with me when you cited that to reduce torts is to reduce the number of incidents leading to malpractice suits. For me, this was truly getting to the root cause as opposed to addressing the symptoms. Thanks for providing that eureka moment! Really enjoy your podcasts!

Comments are closed.