Last week was an amazing week of learning and networking. I was in Dallas for the Lean Healthcare Transformation Summit (as I wrote about). As I mentioned yesterday, it was also my wife's five year reunion from her MIT master's program. As I also mentioned, I nerded out and sat in on a number of lectures that were part of the weekend.

I'll also blog later about Steve Spear's lecture (you likely know him from the Lean community), but I also really enjoyed a lecture by MIT professor Zeynep Ton, from the Sloan School of Management (she's formerly of HBS… and also an industrial engineer, like me).

Prof. Ton gave an engaging lecture on her book The Good Jobs Strategy: How the Smartest Companies Invest in Employees to Lower Costs and Boost Profits. I had heard of the book but hadn't yet gotten to the Kindle sample that I downloaded, yet alone the full book. The Kindle version is only $5.99, by the way, or it's free if you have a “Kindle Unlimited” membership.

I've finally read the book and I highly recommend it.

Bad Jobs

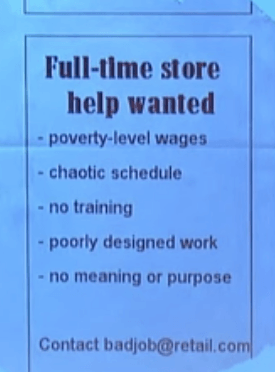

Ton framed the problem in retail workplaces as a “bad jobs strategy” that is, sadly, the norm in retailing (the area in which she has focused her research). This strategy causes many problems for employees, as well as for us, as customers. In bad jobs, people are treated like robots… or they're not trained and they're left to fend for themselves in chaotic environments. In bad jobs, people aren't certain how much they're going to work or earn in a week… and they're not able to really hold down a second job because of their changing and unstable schedules.

A realistic ad for a bad job might look like this (from this video of Ton):

See a post I wrote in 2007 about complaints about Walmart's scheduling practices that try to chase demand with staffing levels in 15-minute increments. Their approach might minimize waste, but is it respectful of the people doing the work and their lives?

In bad jobs companies, people say “We are throwaways. A dime a dozen. Human robots.”

This strategy is bad for workers, but it can also be bad for companies (although she says a company CAN make money with the “bad jobs strategy” – it's just at the expense of workers and/or customers.

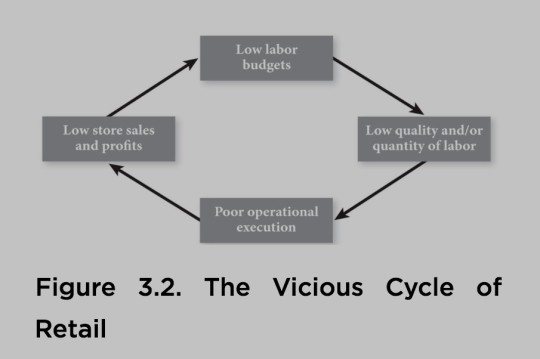

She describes a “vicious cycle” that could also be called a “negative reinforcing loop” for those who have studied system dynamics, where things get worse and worse as you keep going through a cycle.

The diagram is a bit more clear in the book:

It's not clear to me where the cycle starts necessarily… maybe it depends on the organization. As Ton pointed out, too many retailers view employees as a cost, a line item to be managed in budgets and the P&L statement.

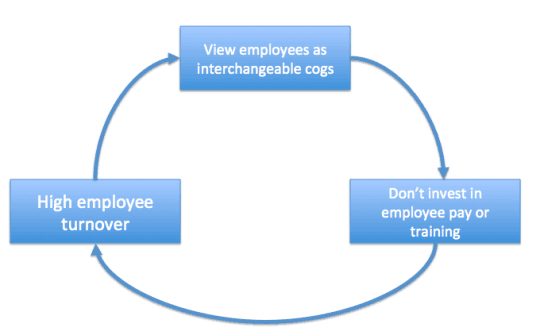

Ton said that many retailers who pursue a “low cost strategy” (think Walmart, for one) might convince themselves that the only way to be a low cost retailer is to pay low wages, to staff stores at a bare minimum level, and to not invest much in employees. There's probably a different vicious cycle related to that (my drawing, not hers):

Ton points out that there ARE organizations that choose a different path, something she calls “the good jobs strategy.” There are retailers who manage to compete in low-cost industries that invest in their employees and don't treat them like mindless cogs in a machine.

Listen to Mark read the post (subscribe to the series):

Are Hospitals Mostly Pursuing the “Bad Jobs Strategy?”

My observation is that most hospitals, unfortunately, have chosen the “bad jobs strategy” — and patients and medical professionals suffer as a result (which arguably hurts their bottom line). Hospital jobs usually rank high in having meaning, but they might be bad jobs for other reasons.

It's a fact that labor costs are the highest single line item in a hospital's annual budget and spending. It's typically 60-70% of the budget. It's natural that executives would look first to trying to reduce or minimize labor costs as a way of boosting their bottom line.

But, are they also getting into that vicious cycle that Ton describes? Even if the hospital offers competitive wages, the number of labor hours is usually prescribed to a number that is measured and managed on a daily basis. Being understaffed leads to poor quality work and worsened outcomes for patients.

Hospitals also make choices that undercut their ability to improve workflows and processes. The typical game plan for a hospital is to look at the amount of direct work to be done – such as the patient census or volumes – and then adjust staffing accordingly. Nurses rightfully complain about being sent home early when census is lower than expected. The hospitals say things like they “have to send nurses home,” but it's really a choice.

The alternative choice would be to pay nurses or other staff to do indirect work, such as process improvement. Too many hospitals send a message that they only value a nurse for their ability to do direct patient care, but they do not value their creativity or ability to help improve patient care. That can create job dissatisfaction and turnover, which can lead to other problems.

The issue of having your schedule changed too frequently (being sent home or having to be “on call”) can be a dissatisfier, as well. Hospitals might typically say they “have to” match staffing to demand (or workloads) because it seems like the fiscally responsible thing to do. It's easy to see how much you save by sending somebody home. It's much harder to see the cost of employee dissatisfaction and the resulting quality and service problems that might result from making employees mad because they aren't able to earn a full day's pay as they expected.

In the book, Ton explains how Costco might ask for volunteers to take a few hours off if demand is lower than expected. If nobody volunteers, Costco “eats the cost” and they're able to use employees' time in other ways since they are generally more broadly cross trained than employees at most stores.

The Good Jobs Strategy

What what is this better strategy that's used by retailers like Costco, Trader Joe's, and other very successful companies?

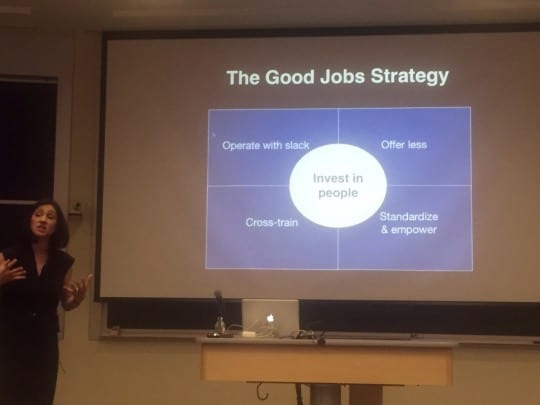

The components are:

- Offer less (don't try to sell all things to all people)

- Standardize AND empower (have standards, train people well, engage them in improvement)

- Cross train (another way to invest in people that pays off for the company and customers)

- Operate with slack (don't insist that everybody is busy all of the time)

- Invest in people (pay them well, treat them well, train them well)

As Ton points out, this is a SYSTEM, where you can't pick and choose just one or two of these strategies. That should remind you of Lean, by the way. This strategy works because it all works together in a very interconnected and mutually supportive way.

You can read more about this in her HBR article: “Why “Good Jobs” Are Good for Retailers” (or buy the book, of course).

As I say all the time about Lean in healthcare, this strategy benefits everybody: customers, employees, and company. In healthcare, it's patients, employees & physicians, and health system. Everybody wins.

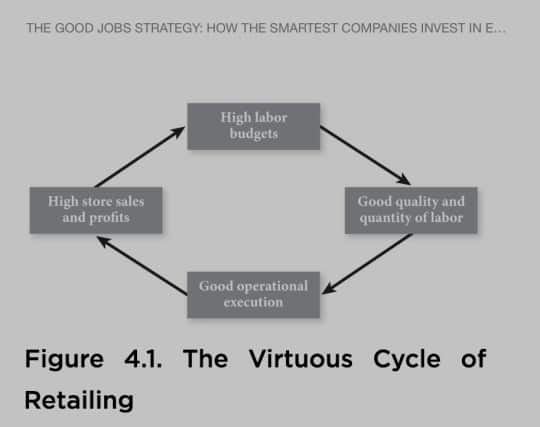

As Ton illustrates, a “virtuous cycle” gets created (a “positive reinforcing loop”):

I could write a blog post on each of the five “Good Jobs” points (and I've already written about them a lot on this blog), so let me focus on…

The Importance of Slack

Being overstaffed is bad if we're spending money and employees aren't accomplishing anything of value. Yet, trying to keep everybody 100% busy means either that we create long waiting times for customers (or patients). Or, we create disgruntled workers when we jerk around their schedules or send them home early.

In the book, Ton describes the benefits of being a bit OVER-staffed. But, again, this is often the right long-term strategy. In retail, being understaffed might mean you're throwing away revenue as customers balk at long lines. In healthcare, understaffing can hurt patient satisfaction or, more importantly safety and quality — what does THAT cost you?

Also see my previous post about why it's not a good idea to try to keep people 100% busy.

I love a book that is all about the need to not be 100% busy: Slack: Getting Past Burnout, Busywork and the Myth of Total Efficiency.

Alan Robinson and Dean Schroeder wrote about the need for “slack” in their ASQ article “The Role of Front-Line Ideas in Lean Performance Improvement,” highlighting a Scania truck factory in Sweden:

“To ensure workers have enough time to implement the improvements, every team has built-in slack; it is deliberately “over staffed” by two positions. If additional resources or authority are needed for a specific idea, it is escalated up to the idea board of the next level of management.”

Slack time can be used in many productive ways:

- Training in your existing speciality

- Cross-training in new tasks, roles, or areas

- Participating in continuous improvement

- Providing better service or care to your patients

Just as no organization was ever “forced” to lay off employees in a bit of a downturn, no organization is “forced” to send people home early.

I Got Cited…

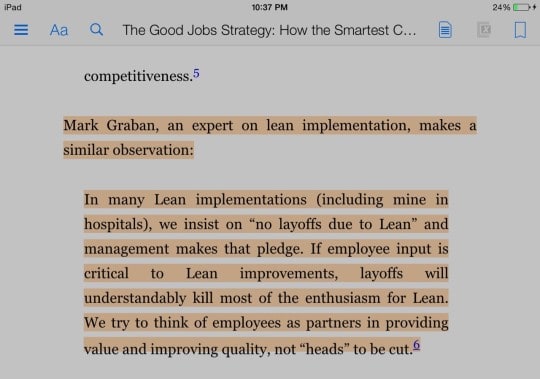

When I introduced myself to Professor Ton after class, she recognized my name and that I'm a graduate of the MIT LGO program. She said, “I quoted you in my book!”

That's not the only reason I bought the book that day, of course. I will admit to using the Kindle search function to find my name and the reference before going back to Chapter 1 to start.

The excerpt:

She was citing this blog post — To Layoff or Not To Layoff — That Really is a Question.

There's so much I could say about the book and this approach. Readers of this blog might be “the choir” in terms of “preaching to the choir” on these topics, but I hope you'll check out the book.

Also, you can see this TedX talk for an introduction. Maybe watch this video at a leadership team meeting and discuss how this strategy can benefit you, even if you're not a retailer:

Let's create more “good jobs” environments in healthcare!

Do you think your organization is more of a “bad jobs” or “good jobs” environment? If it's a “bad jobs” environment, how do employees and customers (or patients) suffer? Can you see a financially successful future in which “good jobs” are the norm for your organization?

What do you think? Please scroll down (or click) to post a comment. Or please share the post with your thoughts on LinkedIn – and follow me or connect with me there.

Did you like this post? Make sure you don't miss a post or podcast — Subscribe to get notified about posts via email daily or weekly.

Check out my latest book, The Mistakes That Make Us: Cultivating a Culture of Learning and Innovation:

Here’s a new interview with Prof. Ton that appeared in The Atlantic:

“Good Wages Are Not Enough”

In part, something that reminds me of Lean:

And an article about “toxic” retail jobs for more background on this topic:

“I work in retail, and ‘on-call’ scheduling makes it toxic”

[…] Zeynep Ton (see my post on her book The Good Jobs […]

[…] see the book The Good Jobs Strategy for stories of retailers who do things the right […]

Here is Prof. Ton being interviewed on CNN last weekend. Watch the segment here.

Ton and the host talk about “the Toyota revolution.”

[…] Ton give a lecture at an MIT alumni event back in June and immediately bought and read the book (read my blog post about the book and parallels to Lean and healthcare). I highly recommend it and I wish more […]

[…] Visiting MIT, Learning about “The Good Jobs Strategy” for Retail (and Healthcare?) […]