My friend Ryan, who works at a hospital in Canada, sent me a few pictures of an Industrial Engineering textbook that he used almost 20 years ago.

My friend Ryan, who works at a hospital in Canada, sent me a few pictures of an Industrial Engineering textbook that he used almost 20 years ago.

He wrote:

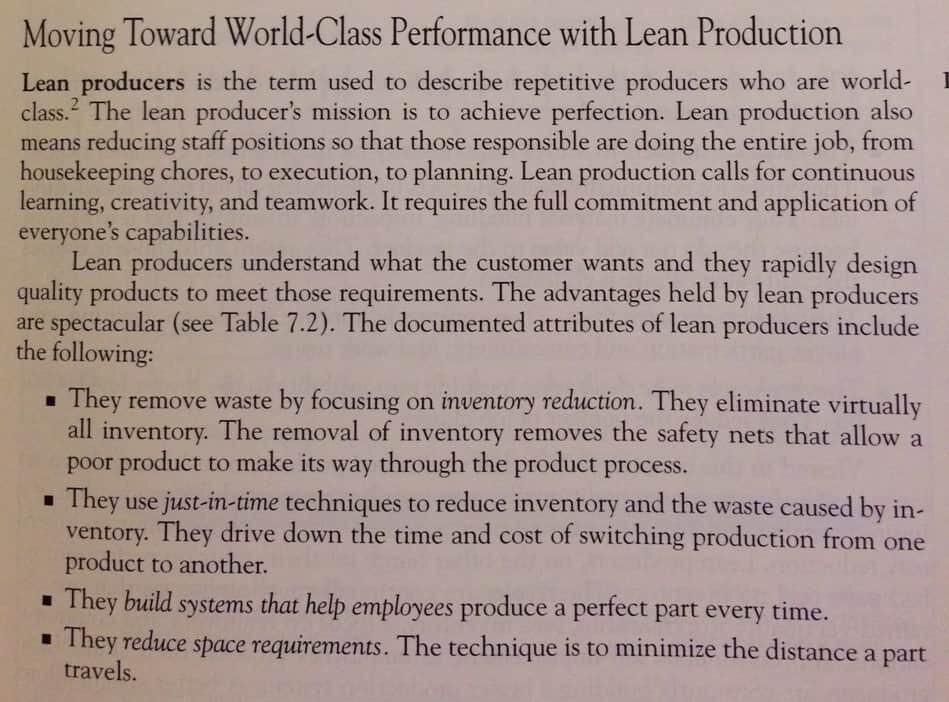

“I was cleaning up my upstairs when I came across a textbook from 1996 from my Industrial Engineering undergrad studies. On a hunch, I wanted to check their views on lean.

Overall, they define some of the principles well. What caught my eye was the third sentence:”

Hmmm… the first sentence about “repetitive producers” doesn't seem very accurate to me. Sure, Toyota builds approximately 1000 cars or trucks a day in a plant, but each one isn't the same. There are many lower volume / high mix manufacturers who use Lean methods. When you define Lean as a management system and a culture, it's widely applicable (including in healthcare, of course).

Sentence two — The mission is perfection. Sure… the 5th principle of Lean in the book Lean Thinking is the ongoing and never-ending pursuit of perfection. That's fine.

The third sentence… “reducing staff positions” — that's off to bad start. Do they mean reducing the number of employees or reducing the number of roles and job titles? That's not written clearly.

Yes, it's true that Lean organization usually needs fewer employees, but it's well known that using Lean to drive layoffs will really hurt morale and crushes any chance you have of people participating in meaningful continuous improvement. That's why many of the best Lean healthcare organizations have some form of “no layoffs due to Lean” commitment. See my blog posts about this, including this recent one about the CEO of Scripps Health.

It's possible to use attrition to reduce headcount levels over time, but that's an end result of process improvement, not the primary goal.

The rest of that third sentence isn't quite right in terms of Lean being about everybody doing everything. Sure, a Lean auto plant has less division of labor amongst skilled trades roles. Production workers would be allowed to do some light maintenance work that might have traditionally been done by a higher-paid skilled tradesperson. But, I wouldn't extend this definition of Lean to a hospital. I don't think nurses should be pulling double duty as housekeepers, for a number of reasons (but some hospitals are doing this).

For one, nurses are paid more than housekeepers. It makes sense to let nurses focus on patient care and nursing duties – for financial reasons and reasons of professional pride and a sense of accomplishment. It's easier to hire and train more housekeeping staff. Saving a bit of money by having fewer housekeepers might mean higher costs in other areas. If nurses don't have enough time for patient care, we might see a higher number of patient falls and pressure ulcers.

From the rest of that textbook definition, it's true that Lean “calls for continuous improvement, creativity, and teamwork” and that we get “the full commitment and application of everyone's capabilities.” Sure, there might be a moment when a nurse could help a housekeeper (in the name of teamwork) but I think nurses shouldn't have to do that all the time — so that we can fully utilize their nursing capabilities. If nurses are having to help housekeeping too often, maybe the hospital needs more housekeepers?

In their glossary, the first definition is totally worthless (what does “world class” mean?) but the second definition isn't bad:

Be Careful About Reducing Inventory

I think the textbook definition also errs in making is sound like inventory reduction is a primary goal. Lower inventory is the end result of better systems, better problem solving, higher quality (building in quality at the source), and improving flow (by reducing batches, etc.).

The admonition that “they eliminate virtually all inventory” was followed by some manufacturers and many of them got into trouble because they reduced inventory too much… they reduced inventory beyond that was necessary for their system, their customers, and their variation.

When I did a grad school internship at Kodak in 1998, their semiconductor fab had gone too far in eliminating finished goods inventories. They became an awful bottleneck in the supply chain for high-dollar professional digital cameras that were being purchased by photojournalists. Reducing inventory too much was leading to delayed or lost sales of $15,000 cameras. Oops. They had too much variation in the lead time and yield of the semiconductor image sensors to have such low finished goods stocks, so they were forever trying to play catch up.

The misapplication of “just in time” leads to publications like the Wall St. Journal constantly harping on the “risks” of JIT and Lean strategies. Yeah, there's a risk that you reduce your inventories too much… so don't do that! Read more about this topic in a past blog post.

Hospitals that are applying JIT principles to their supply chains need to be careful too (see this article). The sub-headline says it can be a “risky” strategy.

Just-in-time isn't without financial risk, however. The biggest — and the reason it took this type of inventory management a while to catch on in healthcare — is the potential lack of availability of a product under the system, said Spence. “Hospitals take financial risks everyday, but the one they don't want to incur is a patient event becoming a negative event.” For example, occasionally, situations arise where a patient procedure must be rescheduled because an implant, due to arrive the night before, is unavailable, said Spence. Then the surgery must be moved, which costs the facility more money.

“If you carry inventories under JIT that are so low that the product's unavailable because of one incidence, that can be hugely adverse in the hospital sector,” he said.

Right, so be careful NOT to do that. If a particular hospital supply is small and/or inexpensive, then you don't need to keep inventories or safety stocks that low. If an item is critically important, don't let inventories get too low, even if the item is expensive.

Lean isn't about low inventory at all costs. It's about the overall effectiveness of the system.

More than ten years ago, I had a Japanese sensei with me at another factory that had inventories that were too low.

He told me:

Job 1: Make deliveries to customers on time

Job 2: Low inventory

Wise words, for manufacturing OR for healthcare.

Please scroll down (or click) to post a comment. Connect with me on LinkedIn.

Let’s build a culture of continuous improvement and psychological safety—together. If you're a leader aiming for lasting change (not just more projects), I help organizations:

- Engage people at all levels in sustainable improvement

- Shift from fear of mistakes to learning from them

- Apply Lean thinking in practical, people-centered ways

Interested in coaching or a keynote talk? Let’s talk.

Join me for a Lean Healthcare Accelerator Trip to Japan! Learn More