I've been a big fan of Dr. Atul Gawande's writing for a long time (see previous posts about him and his work).

His latest article is out, which I was able to read last night. It just came out (or I first heard of it yesterday).

It's a well written piece that talks about the waste of unnecessary care in this country. Gawande cites the 2012 Institute of Medicine study that says “unnecessary care” costs the U.S. $210 billion a year.

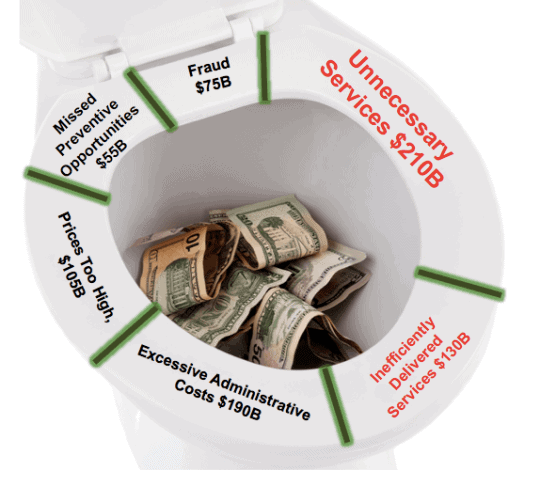

See this “toilet pie chart” that I made for a Gemba Academy webinar on waste a while back:

We are flushing money down the toilet.

Gawande's piece highlights examples of people who received unnecessary care (including his mother and one of his own patients) or almost did.

From the article:

“The researchers called it “low-value care.” But, really, it was no-value care. They studied how often people received one of twenty-six tests or treatments that scientific and professional organizations have consistently determined to have no benefit or to be outright harmful. Their list included doing an EEG for an uncomplicated headache (EEGs are for diagnosing seizure disorders, not headaches), or doing a CT or MRI scan for low-back pain in patients without any signs of a neurological problem (studies consistently show that scanning such patients adds nothing except cost), or putting a coronary-artery stent in patients with stable cardiac disease (the likelihood of a heart attack or death after five years is unaffected by the stent). In just a single year, the researchers reported, twenty-five to forty-two per cent of Medicare patients received at least one of the twenty-six useless tests and treatments.”

He writes about situations where the risk of a procedure doesn't seem to be outweighed by the benefits. There's one shocking story where the doctors gauged a procedure a success (“We're going to put this one in the win column”) even though the patient had suffered a stroke during the procedure and was like “the walking dead” afterward.

A lot of the unnecessary care increases risk and hurts outcomes (such as unnecessary CT scans causing higher cancer rates). Should every slow growing cancer (a “turtle”) be aggressively treated if the risks outweigh the benefits?

In the Lean methodology, value is defined by the patient (in terms of outcomes and quality of life, as Don Berwick has talked about). But, the doctors know more about medicine than we do as patients and they can be very influential in shaping our decisions, even if it's not really the right thing for us. This is one way healthcare is far more complex than you or me buying a car where we can more specify “value” by deciding what we're willing to pay for.

We often don't have to pay more for choosing more healthcare, which is one distortion in the system.

“The virtuous patient is up against long odds, however. One major problem is what economists call information asymmetry. In 1963, Kenneth Arrow, who went on to win the Nobel Prize in Economics, demonstrated the severe disadvantages that buyers have when they know less about a good than the seller does. His prime example was health care. Doctors generally know more about the value of a given medical treatment than patients, who have little ability to determine the quality of the advice they are getting. Doctors, therefore, are in a powerful position. We can recommend care of little or no value because it enhances our incomes, because it's our habit, or because we genuinely but incorrectly believe in it, and patients will tend to follow our recommendations.”

Gawande also revisits the excessively high healthcare costs in McAllen, Texas (which he wrote about in 2009). After the publication of the article, physicians focused on not recommending, for example, expensive home health care without considering the cost and tradeoffs. There were attempts to reduce outright fraud and other violations of the law. Also, Accountable Care Organizations (ACOs) helped reduce utilization by focusing on primary care and better chronic disease management, which has helped reduce costs and reduce mortality.

As Lean thinkers, we shouldn't just pay attention to the “inefficiently delivered” part of the pie chart. We should support the efforts of clinicians and others who are trying to reduce unnecessary care or what we might call the “waste of overproduction” in Lean speak. We shouldn't be trying to do the wrong things (provide the wrong care) righter.

What are your thoughts on the article? What is your organization doing to reduce unnecessary care? What more could be done?

Please scroll down (or click) to post a comment. Connect with me on LinkedIn.

Let’s build a culture of continuous improvement and psychological safety—together. If you're a leader aiming for lasting change (not just more projects), I help organizations:

- Engage people at all levels in sustainable improvement

- Shift from fear of mistakes to learning from them

- Apply Lean thinking in practical, people-centered ways

Interested in coaching or a keynote talk? Let’s talk.

Join me for a Lean Healthcare Accelerator Trip to Japan! Learn More

We recommend Gawande’s various books/articles to the legal professionals we work with. If there is one place with overproduction, it’s a law firm! The risks and benefits (and costs) are very different, but the essence of the problem is the same: lawyers tend to provide unnecessary services under the guise of “just in case.”

My wife, who is a physician at a major cancer center, tells me that one of the major drivers of unnecessary care is the lack of communication, coordination, and planning among family members. The patient himself might be happy to pass on a procedure, but the family feels compelled to do *everything* possible to help their loved one — even if the likelihood of success is near zero. She’s actually dealt with cases where she tells the family that the procedure will make absolutely NO difference, and they still ask her to do it.

By no means am I suggesting that Gawande is off-base; I’m only pointing out that irrespective of the information asymmetry, patients and their families bear some responsibility.

A different type of information asymmetry.

What is the obligation of a physician to refuse to do a procedure that, in their professional opinion, will not help at all? Do they open themselves up to malpractice suits?

Love Dr. Gawande’s articles. He really tells it like it is. Thanks for posting, Mark.

It would be great to see a list of the 26 tests he refers to, or some other aid to determine whether the tests doctors recommend are really necessary.

I would like to state Cindy Jimmirson study where she observed the system for 3 years day and night and found waste in healthcare is 60% and that is clinical and non clinical waste.

As for the oncology practice, it is only one aspect of many existing treatments and I know 1 doctor refuses giving unnecessary treatment even if the patient will go to another physician, but how many like him ?! And this is in my part of the world : lebanon

Sure… it’s possible that 60% of the work in certain areas is waste. Berwick and others estimate 30% of our spending is waste.

Comments are closed.