Yesterday, Thomas Eric Duncan, the first person diagnosed with Ebola in the U.S. died in a Dallas hospital.

As I've been following this story, I keep thinking about bad systems and bad processes. Sometimes, there's a lack of planning and sometimes it's a lack of proper execution, it seems. I'm not spending much time asking “who screwed up?”

Liberia, where Duncan traveled from, had airport checks that relied on voluntary disclosure (Duncan lied) and temperature checks (he was not yet symptomatic).

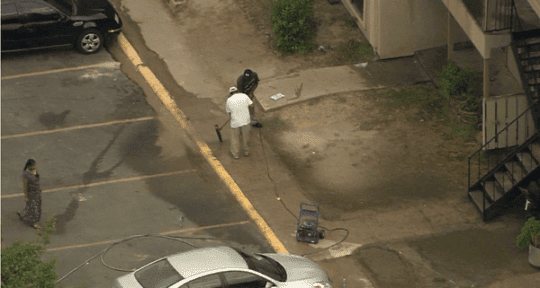

Cleaning crews (without proper protective gear!) eventually cleaned up Duncan's Ebola-laced vomit from outside an apartment building (it had sat there for days)… see below (and read about it).

The people Duncan stayed with were left in that apartment for days, with armed guard outside (to keep them in and keep them safe), but they complained that nobody was bringing them food. Students who had been exposed to Duncan weren't removed from school for a few days. The CDC didn't send a proper clean up crew for days… the sweat-stained sheets from Duncan were still inside the apartment. The family didn't know what to do with the sheets and mattress. They were cleaning the apartment themselves with bleach. Officials argued about the method needed for disposing and transporting the waste.

Bad systems? Poor planning? It sure seems so. See “Five blunders US made in treating country's first Ebola patient.”

And, at the hospital, there were stories about problems with systems… later retracted by Texas Health Resources.

Initial reports came out about Duncan being discharged from the emergency department, even after telling a nurse he was from Liberia. The doctors supposedly didn't hear about the Liberia connection and thought he was just a guy with stomach pains, decreased urination, and a low-grade fever. They didn't assume Ebola. They sent him home… only to have him get worse, expose a bunch of people, and end up coming back in an ambulance.

News reports blamed the Electronic Health Records (EHR) system and “workflow problems.”

I was happy that individuals weren't being blamed and thrown under the bus, for once. It was good to be happy about something related to this case.

In the facility's electronic health record (EHR) system, though, nurse and physician workflows were separate. That means the travel history the nurse entered into the hospital's Epic Systems EHR didn't automatically appear in the physician's standard workflow, the hospital said in a statement summarized by Healthcare IT News.

The hospital statement read, in part:

Protocols were followed by both the physician and the nurses. However, we have identified a flaw in the way the physician and nursing portions of our electronic health records (EHR) interacted in this specific case. In our electronic health records, there are separate physician and nursing workflows.

The documentation of the travel history was located in the nursing workflow portion of the EHR, and was designed to provide a high reliability nursing process to allow for the administration of influenza vaccine under a physician-delegated standing order. As designed, the travel history would not automatically appear in the physician's standard workflow.

As result of this discovery, Texas Health Dallas has relocated the travel history documentation to a portion of the EHR that is part of both workflows. It also has been modified to specifically reference Ebola-endemic regions in Africa. We have made this change to increase the visibility and documentation of the travel question in order to alert all providers. We feel that this change will improve the early identification of patients who may be at risk for communicable diseases, including Ebola.

The hospital said they had corrected or updated the workflows and wanted other hospitals to learn from their problems (I didn't think any EHR/EMR system had ever been updated that quickly before). It's a “teachable moment,” said the CDC head.

In response to questions raised about Mr. Duncan's first visit to the hospital emergency department on the night of September 25th, we have thoroughly reviewed the chain of events. In the interest of transparency, and because we want other U.S. hospitals and providers to learn from our experience, we are, with Mr. Duncan's permission, releasing this information.

But, late Friday, the hospital put out a new statement saying the workflow hadn't been a problem and physicians should have seen the travel information on their screen in the system:

We would like to clarify a point made in the statement released earlier in the week. As a standard part of the nursing process, the patient's travel history was documented and available to the full care team in the electronic health record (EHR), including within the physician's workflow.

There was no flaw in the EHR in the way the physician and nursing portions interacted related to this event.

So how did this happen? Bad processes? Bad planning? THR had received Ebola information before Duncan arrived. But, they didn't put the pieces together and they sent him home.

What's your take on this situation? Can we get better at anticipating problems and improving workflows, processes, and systems in advance? Can we learn from each other to avoid having to all make the same mistakes? How can we better protect caregivers, first responders, and the public? Or are we just not very good at systems and processes… at being proactive?

What do you think? Please scroll down (or click) to post a comment. Or please share the post with your thoughts on LinkedIn – and follow me or connect with me there.

Did you like this post? Make sure you don't miss a post or podcast — Subscribe to get notified about posts via email daily or weekly.

Check out my latest book, The Mistakes That Make Us: Cultivating a Culture of Learning and Innovation:

There are many bad processes involved, sadly.

But the most serious to me, is we have unrealistic proposed processes for dealing with an epidemic. This is potentially catastrophic but I know of no serious efforts to find realistic strategies. I am sure there are plenty of smart people working on things in isolation.

But the huge amount of waste on security theater and trying to spy on everyone would be much better spent on things that will actually make us a safer society. I don’t think the answers are simple, but if we don’t take seriously how critical it is to plan better to cope with epidemics we will be sorry. And the money in the billions is there to do so – all we have to do is stop spending money on the atrocious things the Department of Homeland “Security” is spending money on now.

The science seems pretty clear that ebola is not going to be a series epidemic in the USA. But something else may well be and we are pitifully prepared to cope with it. We continue to increase the odds of such an event with very bad antibiotics practices http://engineering.curiouscatblog.net/2013/03/08/cdc-again-stresses-urgent-need-to-adjust-practices-or-pay-a-steep-price/ and foolishly failing to take vaccines creating the perfect conditions for epidemics.

Even worse though is how poorly we (as a global society) dealt with the initial conditions in Africa and our continuing efforts. We had poor processes in place. We didn’t commit funds early enough. We got behind and are not doing enough now. Lots of people are taking heroic action in Africa but without good processes it isn’t enough.

Thanks for the comment, John. Part of the “bad system” in Africa is a lack of proper supplies — a lack of gloves, soap, and basic things that are needed for treating any illness, yet alone Ebola. I guess the causes and root causes of that could be debated for a while and we could ask what the role or responsibility of the West is.

There’s some “Ebola theater” going on where Dallas schools are installing infrared temperature sensors to detect kids with fevers… but some say the technology doesn’t work (reminds me of the TSA airport scanners). Some airports in the US are installing this same technology.

What the USA’s role should be in helping people outside the USA is indeed a tricky question.

Even if you take the position those in the USA don’t believe other people are worth protecting (which I don’t believe) just a purely selfish government with an understanding of science and epidemics understands the risks of external disease vectors.

Just like those failing to use vaccines create a risky health system that everyone suffers from when things go bad, ignoring disease until it strikes your body is a bad way to protect yourself.

Plus when rich countries like the USA show disregard for people living elsewhere that drastically increases terrorism risks. Coping with that by allowing frustration to grow feeding crazy people’s use of terror and then trying to spend hundreds of billions on weapons and the like is a lousy strategy.

It isn’t like this is some shocking idea. Pretty much everyone that studies this understands that link. In the Bush administration they talked a lot about it and did some things especially with Karen Hughes. But even forgetting any terrorism concerns or humanitarian feelings, allowing dangerous virus and bacteria to infect lots of people (anywhere in the globe) is hugely dangerous for rich countries health. It is just a hugely foolish (looking at it completely selfishly and even when doing that ignoring positive externalities of action and negative externalities of inaction) to stand by while dangerous epidemics grow.

I believe the first reason to act is because all people matter, not just those inside your border. But even for people that don’t care about that the completely selfish reasoning means not acting is foolish. And an understanding of disease makes it obvious you need to act a long time ago. Yes after failing to act more sensibly for a decade or more we should have acted drastically a few months ago. But even that would have been too late. Though actually for Ebola from a 100% USA selfish perspective it might not be too late – because it is likely like to become a huge problem in the USA. But something similar easily could and we have failed to prepare (which in this instance means failed to make sure the larger global health system is much better able to cope).

Two headlines from Spain:

“Spanish nurse Ebola infection blamed on substandard gear and protocol lapse”

“Ebola outbreak: Spanish doctors at Teresa Romero Ramos hospital only had ’10 minutes training’“

I was fascinated with the video about this Ebola killing robot that some hospitals are using to clean rooms as part of their housekeeping. I really liked the error proofing in the video too.

http://www.dailymail.co.uk/sciencetech/article-2783407/Ebola-killing-ROBOT-destroy-virus-minutes-Little-Moe-uses-flashes-25-000-times-brighter-sunlight-kill-diseases.html

In Spain:

“The Spanish nursing aide infected with Ebola believes she might have caught the virus by touching her face with a gloved hand after treating a missionary brought here from Sierra Leone, a doctor said Wednesday.”

LINK

Authorities will blame “human error” but this sounds like a systemic problem:

“Other medical workers have said their training on the protocol had been inadequate. In August, authorities at Carlos III hospital called in staff to explain how to put on and remove protective gear, one worker in the quarantine unit said. Many who, like herself, were on vacation were later briefed by colleagues but got no formal training, she said.”

And from this article:

“Maria Teresa Romero Ramos, a Spanish sanitary technician who became the first case of Ebola transmission outside of Africa, said she followed all the appropriate protocols when entering the room of an Ebola patient at Carlos III Hospital, but she acknowledged that she may have made a mistake when removing her protective suit.

“I think the error was the removal of the suit,” she told Spanish newspaper El País by phone. “I can see the moment it may have happened, but I’m not sure about it.””

New headline from Texas… with no discussion of how or why the nurse got Ebola:

“Texas nurse tests positive for Ebola, would be 1st Ebola transmission in U.S.”

“It’s not clear whether the health care worker in the second Ebola case contracted the disease during Duncan’s first visit to the hospital or after he was isolated.”

As I suspected, a “breach of protocol” in Dallas.

CDC director: Second case of Ebola in US result of ‘breach of protocol’

How do we better protect humans against human error? What can we learn from this? Why was the protocol violated?

An article on the preparation (or lack thereof) and some of the drills hospitals are running:

LINK

Another good read:

“American nurse with protective gear gets Ebola; how could this happen?”

Triple gloving seems like an example of “best efforts” that aren’t really the right protocol. Who is educating nurses and other clinicians about what NOT to do? Are they doing enough to teach and supervise protocols that they should be following?

Another article:

CDC head criticized for blaming nurse’s Ebola infection on ‘protocol breach’

I don’t hear the nurse being scapegoated anywhere. I hear talk about system problems. Maybe some in the general public say “bad nurse,” but I don’t

Yes, these are system problems. A lack of training and a lack of preparation… those are system problems that need to be fixed.