Two pet peeves of mine are hearing people say things like “Lean is all about reducing waste” and or “Lean is all about cost cutting” (and thankfully others are also trying to dispel that myth). Another pet peeve is people drawing conclusions off of two data points, but we'll come back to that later in this post.

Lean is not “all about” waste — we also focus on providing the right “value” to the patient or customer (doing the right thing the right way at the right time and the right place). Reducing waste is a big part of Lean, but it's not the only thing.

Of course, we know that reducing waste is not exactly the same as “cutting costs.” Reducing wasteful activity in a process or value stream will often lead to lower cost, but it also leads to better flow and better quality, among other things.

Hospitals have often focused on cost cutting, which often means layoffs, since 60 to 70% of a hospital's budget might be labor. Lean, of course, provides an alternative to layoffs. “Cost cutting” might actually increase waste (and often increases costs, ironically).

This article from Becker's Hospital Review caught my eye:

Lean management for cutting costs and a happier hospital

It's a good article, as it helps dispel the myth that “Lean = cost cutting.”

When many people think about lean management, one thing comes to mind: cutting costs. However, by looking at lean management from a broader perspective, healthcare organizations can achieve much more than cost savings.

If many people think that, then they would be wrong.

If “many people” think that Lean is about “cutting costs,” then there's been a failure to communicate. My book (and others) make it clear (or so we think, as authors) that Lean is not about simple cost cutting. But, how many people profess Lean expertise without having read much about Lean?

The article talks about Mountain States Health Alliance, under the guidance of Simpler Consulting, and how they improved care and created a better workplace.

Before beginning its transformation, Mountain States identified three goals to be achieved: improve patient outcomes and satisfaction, increase team member satisfaction and reduce turnover, and provide better value for patients.

That's a more accurate set of goals for Lean than “cost cutting.”

The health alliance has been involving patients in Lean improvement events, a great practice:

Mountain States has even had patients participate in some of its lean transformation events, which allows patients the opportunity to have their voices heard. “It is also an invaluable opportunity for us to see the patient perspective first-hand — a fundamental principle of lean in healthcare,” says Mr. Wampler.

Two Data Points Are Not a Trend

The only thing that gives me pause is the use of simple comparisons of two data points (something I've written about before related to consultant case studies). Sometimes, a simple before and after, with two data points, can be misleading.

The article says Lean “led to patient satisfaction scores in its ED rising from 80.8 percent to 83 percent.”

Without seeing the rest of the data, we don't know if that's a statistically significant increase. We know 83 is higher than 80.8… but that's all we know. How much “noise” was there in the previous patient satisfaction scores over time?

See this recent blog post about how run charts or “control charts” are better than two data points.

I don't mean to pick on Simpler or Becker's. Maybe it's hard to present time series data in an article like this, although they could show a chart.

My point is that when we see two data point comparisons in our own organizations, we should speak up and ask to see more data. Going from 80.8 to 83 might just be part of the “normal variation” or “common cause variation” in the system. Maybe ED satisfaction will go back down to something like 81.3 or 79.5… that's possible given the type of normal month to month variation we'd normally see in data like that over time.

Two Data Points in the NFL

While much of the recent off-field focus around the NFL has rightfully been on the scourge of spousal abuse and child abuse, concussions and the health and safety of players are still an important problem that hasn't been solved.

I recently saw this headline: “League report says concussions down 13 percent.”

Again, that's just two data points between last season and the previous year. Is this part of a trend?

We have to ask for more than just two data points.

Those are one-year-numbers, but the league's hoping it's a valuable trend.

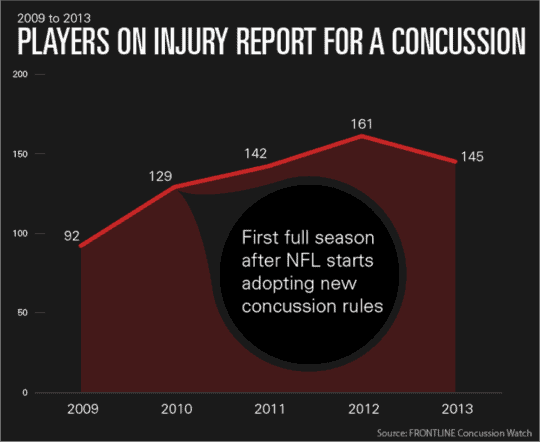

Instead of hoping, we need to look at data. PBS's Frontline shares a little more data on its website, including this chart:

From 2012 to 2013 was a 9.9% decline, going from 161 to 145. I'm not sure how 13% was calculated, unless the NFL's report used different data than Frontline.

Two data points from 2012 to 2013 shows a decline. Comparing 2009 to 2013 shows an increase.

There was a headline in 2010 that said “Concussions reported in NFL up 21 percent from last season.”

Is the problem getting better or is it getting worse?

Is the increase from 2011 to 2012 and the decrease from 2012 to 2013 just noise in a stable system? Or has the system been changing? Advances in new helmets and other rules and technology would represent a change to the system.

As Don Wheeler says in his book Understanding Variation, data have no meaning without context.

Part of the context with the NFL data is that concussions aren't consistently reported (a similar problem as we see with medical errors not always being reported). There might be a smaller number of ACTUAL concussions while the number of REPORTED concussions goes up.

The NFL claimed this was the case in the 2010 article:

“…the league considers [the higher number to be] evidence that players and teams are taking head injuries more seriously. Dr. Hunt Batjer, co-chairman of the NFL's head, neck and spine medical committee, calls the numbers “a great sign” because they show “the culture is changed.”

The same is often said about higher reported medical error rates. Some say it's not because healthcare is less safe, but because more people are honestly reporting problems, harm, near misses, etc. Seems reasonable, but the main point is taking action to then reduce the amount of harm. You can only fall back on “people are being more honest now” for a while before that wears thin.

This is all somewhat messy. The same is true at work. There are no easy answers, but we have to look beyond simplistic comparisons of two data points and we have to understand variation and solid statistical practices.

Please scroll down (or click) to post a comment. Connect with me on LinkedIn.

Let’s work together to build a culture of continuous improvement and psychological safety. If you're a leader looking to create lasting change—not just projects—I help organizations:

- Engage people at all levels in sustainable improvement

- Shift from fear of mistakes to learning from them

- Apply Lean thinking in practical, people-centered ways

Interested in coaching or a keynote talk? Let’s start a conversation.

Hi Mark,

People who know was Lean is can really relate to what you are saying. LEAN is first placing the client or patient at the center of the process, respecting individuals, third: researching and eliminating waste, fourth: standardize the processus, fifth: do continuous amelioration (Kaizen) and last mesure the results. So yes Lean is not only eliminating waste.

Martin.

Hi Mark

Lean is only really good at cost cutting during its early adoption, after you get your mess cleaned up and your work actually flowing, cost reductions pale in comparison to the potential increase in value production you find. In fact cost reduction should never be a goal rather the creation of the most value possible. There is a misconception that all costs are bad, when in fact costs that generate revenue are what you want to be spending money on. The only place cost cutting is worth while is in overhead expenses, because in reality most do not even support the generation of revenue.

Healthcare like any industry has to spend money in order to create value for the consumer, you never really want to reduce that expense you just want to increase they amount of value you provide for those dollars, by doing so you will also increase the revenue you bring in. Like wise overhead expenses that support the creation of value and thus support revenue generation, shouldn’t be cut much either as generally the more value you manage to create the more support functions are required to perform to maintain the revenue production capability. It is only the ivory tower expenses, that actually only eat up money that need to be controlled and cut when ever possible (accounting, finance, much senior management, and a lot of marketing).

[…] when two-data point comparisons (current versus target, current versus last month, current versus last year) where used in a way […]