In November 2012, I had the opportunity to visit Japan for the first time as part of a Lean healthcare study mission. It was fascinating to compare notes with colleagues from the U.S., Belgium, and Holland as we visited factories, including a Toyota plant, and two hospitals that are using the methodology – at least to some extent.

In November 2012, I had the opportunity to visit Japan for the first time as part of a Lean healthcare study mission. It was fascinating to compare notes with colleagues from the U.S., Belgium, and Holland as we visited factories, including a Toyota plant, and two hospitals that are using the methodology – at least to some extent.

One interesting takeaway from the trip was a better understanding of the differences between Toyota's company culture and the typical Japanese business culture. People in the U.S. often complain that it is hard to embrace Lean or to have a “kaizen culture” of continuous improvement because it somehow goes against our national nature, including our tendency to be individualist “cowboys.” Toyota and Japanese Lean companies have different challenges to overcome.

One cultural aspect that fits well with Lean is that Japanese workers, generally speaking, are more willingly follow the routines, or kata, they are taught without questioning things or deviating from them. I was taught that Japanese store clerks all tend to follow the same kata even if they work for different companies. It's basically standardized work, in a Lean context.

However, one Japanese host said, “Kaizen does not come naturally to us.” That statement would probably shock most people, but a similar statement was made at the hospitals we visited. What are the cultural barriers to kaizen in Japan? First is the high value placed on harmony in Japanese society. This leads to organizational cultures where people are afraid or unwilling to speak up or stick their necks out – the tallest blade of grass gets cut. Toyota and other companies have had to work hard to create a climate where people can and do make waves – in a constructive way. It is, in a way, easier for a worker to reach up and pull the physical “andon cord” that hangs over an assembly line than it would be to speak up.

The two hospitals we visited did not have andon cords, but they had some Lean practices and, more importantly, some aspects of Lean culture that they, like Toyota, were working hard to create.

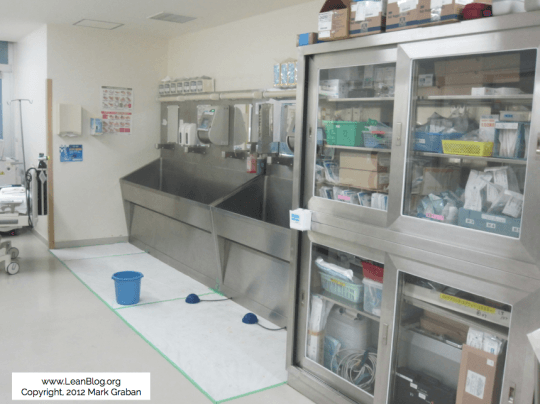

The first hospital we visited had what appeared to be a tools-driven approach to Lean. Their primary focus was on 5S, although it was by no means naturally occurring or consistent across all departments. Some departments, like the operating rooms, looked as messy as any “pre-Lean” hospital in the U.S. (see below).

However, the inpatient units and pharmacy had made a number of improvements in workplace organization. The CEO of the first hospital took inspiration from factories, where workers “have everything they need for their job when they need it.” The CEO set a good example by first 5S-ing his office and by participating in bi-annual 5S audits around the hospital.

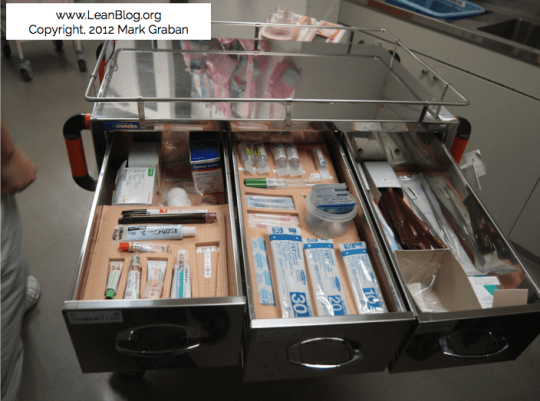

Nurses had used 5S to better sort and organize crutches, cables, and other equipment. Drawers in regular supply carts, crash cart drawers, and the nurses' station desk had foam cutouts or clearly marked areas for each tool or medication, making it easy to see if anything was missing (which could be a matter of life or death in the case of meds).

Most visibly, each nurse had a bag on her hip with the most frequently used items, including hand gel and tape. The bags, when not worn, were hung neatly on designated pegs.

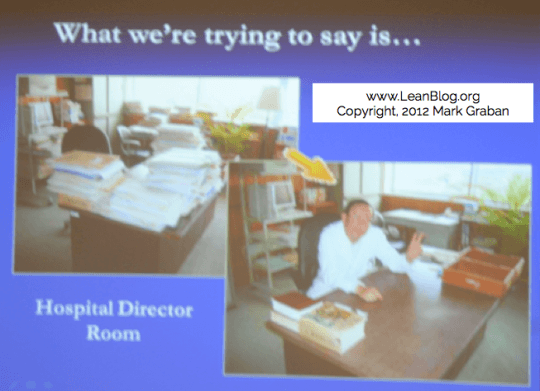

The second hospital we visited had more of a CEO-driven quality culture, with a “Medical Quality Improvement” methodology that had incorporated elements of TQM, Six Sigma, and Lean over time. The CEO emphasized the need to “change minds, including top management” if the organization was going to change. He said, humbly, “We're not sure if we are doing a good job, but we are serious about it.” The hospital, over 20 years of the CEO's leadership, went from bankruptcy to having enough money to build a new hospital. Most Japanese hospitals are losing money today, said the CEO.

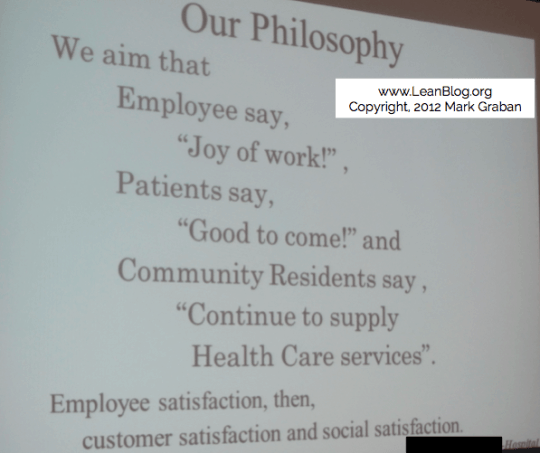

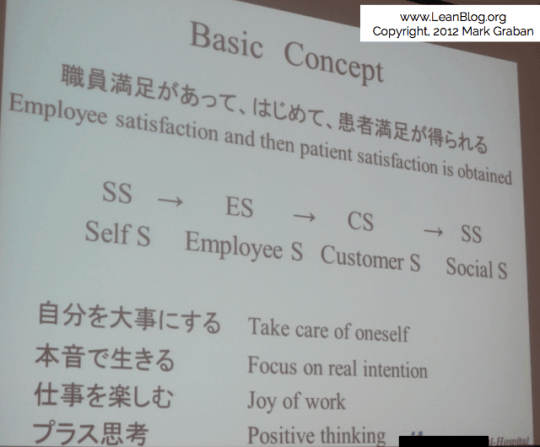

The hospital's philosophy in a few pictures:

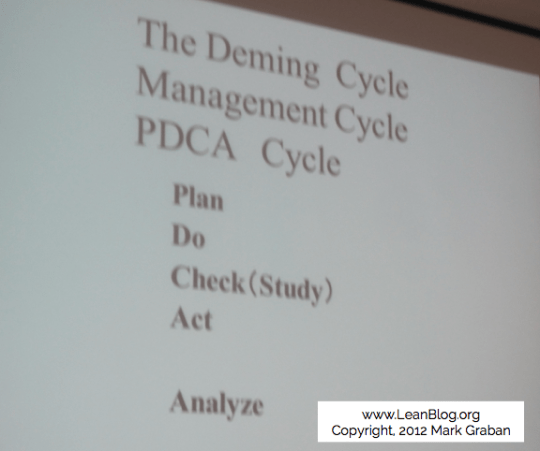

The hospital encourages quality improvement teams to work in annual cycles and each team is required to recruit a physician to participate. The teams, such as one that reduced waiting times for walk-in patients, are taught to follow the scientific method and the PDCA cycle, or the Deming cycle.

Their annual theme for improvement was, “Think for yourself, then act.” The high level process they taught was:

- What is the current situation?

- What are the reasons behind these problems?

- Where are some possible solutions?

- Try out the solutions

- Check – were the solutions effective? What were the results?

- If things improved, then standardize and prevent backsliding

As different as things are in Japanese hospitals, it was all very familiar to the international visitors. As a hospital leader said, “Ideally there would be no Lean or Kaizen program… we'd just do it naturally.”

Let's Go to Japan

I've had a brief chat with Jon Miller from Kaizen Institute and they are considering organizing another Lean Healthcare study tour in late 2014. I'm hoping to go again. Are you interested in joining me and the group? Contact me and we'll send you more information.

A version of this post, without pictures, originally appeared in the ASQ Lean Enterprise Division newsletter. Reprinted with their permission.

Tweet of the Day

"Imposing [14 day goal] before ascertaining resources required… represent an organizational leadership failure," http://t.co/mIi5QnLCAW

— Mark Graban (@MarkGraban) June 10, 2014

What do you think? Please scroll down (or click) to post a comment. Or please share the post with your thoughts on LinkedIn – and follow me or connect with me there.

Did you like this post? Make sure you don't miss a post or podcast — Subscribe to get notified about posts via email daily or weekly.

Check out my latest book, The Mistakes That Make Us: Cultivating a Culture of Learning and Innovation:

There is more than nationality involved in differences of “willingness to comply”.

I was speaking with a highly experienced safety consultant yesterday and he indicated that serious safety events are much more likely to occur because of non-compliance in the healthcare industry than any other he has worked with including nuclear, defense, manufacturing, and aerospace.

I think ambiguity and lack of standards drives much of this difference. Pity the poor nurse who has two call lights going off at the same time and is late with giving meds or changing a dressing. Out of necessity, this nurse must decide which requirement to take on first and which must be delayed.

It even goes much further up the org chart. In much of US manufacturing, failure to comply means the jobs go to Mexico. Not much discussion needed. Many lean leaders get to effectively use command and control based on clear consequences.

In healthcare, it is not always clear who the customer is or even what the customer really wants. From day-to-day, senior leadership is saying that patient satisfaction, patient safety, improved clinical quality (yes, this is different than patient safety), reduced length of stay, EHR implementation, employee satisfaction, or Joint Commission readiness, is the most important thing. Some of this is the nature of the industry but most of this is the failure of hospital leadership to establish priorities (true North).

I have seen lead leaders from manufacture transition to healthcare and are miserable leaders because they lack the sophistication or the ability to decipher what is important.

Much of the problem in healthcare (not just limited to the U.S.) is “inability to comply” rather than “unwillingness.”

Like you said, when a nurse has too much work to do at any one time, that’s a huge problem. That’s a systemic part of the job design and hospitals far too often put staff in a bad situation where they have to cut corners. The nurses are making an educated guess about which work they can blow off or delay while creating the least risk or least harm.

It’s the nature of the industry. It’s fixable, but old habits die hard. We can’t just keep blaming “bad” nurses and “bad” pharmacists.

I don’t think any Lean leader, in any industry, should be using “command and control” to force people to comply or force them to participate in Lean, etc. That’s in and of itself not Lean to do that.

I should have clarified. In some lean manufacturing environments the threat of closure/relocation is so omnipresent that leaders rarely have to justify or explain the reasons why. So when they give direction, the culture is that it will be followed without explanation or a second thought. I am not saying that is always the case or this is the way things should be done. Philosophy aside, in most stable, lean manufacturing environments, the organization with the most inventory turns wins. Most everything else is subordinate at all times. So successfully managing/leading in such an environment doesn’t necessarily translate well to healthcare where there is not a singular focus.

You’re right that there’s more “do or die” competitive pressure in manufacturing. Not too many hospitals around the country are going to be closed because they can’t compete with ThedaCare.

I’m working with Kaizen Institute to do another Lean Healthcare study trip to Japan, the week of November 17. 2014.

Contact me if you’re interested in learning more.

[…] company. So, is it a factor of management, government, or Eastern societies? See previous posts here and here on that […]