Following up on yesterday's post that talked about “the old GM” putting cost ahead of quality, I sometimes I get flashbacks to my days working for General Motors.

I've been in healthcare for 8.5 years now, but at the start of my career, I was an entry-level industrial engineer at the GM Powertrain Livonia Engine plant from June 1995 to May 1997. This plant was in my hometown, Livonia, Michigan and was located exactly 1.3 miles from the house where I grew up. The factory opened in 1971, two years before I was born. The factory closed in 2010 due to the GM bankruptcy and sits empty today as part of the “rust belt” (here is a picture I took fairly recent of the plant and the old sign that used to say GM Powertrain):

Please indulge me with this story that I'm going to tell. I often think about this story, usually when hearing somebody talk about a situation where they are not being allowed to make quality the first priority in their workplace. I recently cringed when I heard GM CEO Mary Barra remind employees that the customer comes first. In my experience, most of the front-line employees knew this – it was leadership who needed to be reminded.

Sadly, people often complain about not being able to make quality the first priority in healthcare. Well, I complained about it when I worked in manufacturing. I have to write the story to get it off my chest (Warning, it's loooong).

An Unbelievably Miserable Setting

I sometimes hold back my GM stories because they might seem unbelievable (like this one I wrote about in 2007). If you find this story unbelievable or suspect my memory is unreliable, let's just call this “fan fiction” or whatever the opposite of “fan” would be. I remember this all pretty clearly, as it was a pivotal moment for me.

The story here, in a way, does seem a bit unbelievable to me, looking back 18 or 19 years… picturing the young, well-intended, if not naive college graduate entering this dark, sad workplace. People working here were pretty miserable. To even be there each day as an hourly worker meant you had at least 35 years of seniority. Those with lower seniority were allowed to stay home or to sit in the cafeteria wasting away as part of the infamous “Jobs Bank.” It seemed backward… those with the most seniority should have earned the right to not work, since those who “had” to stay home still received 90-95% of their pay.

Maybe that's why the workers who had to work were miserable. They were generally tired and worn down by decades in a broken GM factory culture, yet they were there. Many of the salaried employees were miserable, whether they had worked there four weeks or forty years.

It was so dark each day, it was if the factory issued you a personal little dark cloud to hang over your head. So, if it was sunny outside, you'd still have a dark cloud following you around all day to darken your mood. Occasionally, your day would be worse than usual and this cloud would rain on you or throw lightning bolts at your head.

By the way, our plant had pretty much no windows, so you could go an entire five days without seeing the sun in the winter (arriving to and departing from work in the darkness), which added to the depression.

This miserable workplace is why Ive committed myself to the idea that people shouldn't hate coming to work. We spend too much time at work for that. We might not always love it, but we shouldn't hate it every day. Before I started at GM, I had been exposed to the work of Dr. W. Edwards Deming (thanks to my dad, who attended his famous four-day seminar) and I believed strongly in his ideal that people should be able to feel pride and joy in their work, not misery.

Connecting Rods < Engines < Cadillacs

As an industrial engineer, I was assigned to two machining departments that fed parts to the engine assembly line – blocks and connecting rods. There was one block per engine, and there were eight rods per engine. Even with all of our quality problems, I'm certain each engine left the plant with eight rods.

For those who aren't familiar with a rod, these were good solid hunks of metal (solid enough that one hourly employee assaulted another employee with one once).

Now, when I say we “fed” parts to the assembly line, that was certainly the intent and the goal. We were supposed to have plenty of inventory sitting there after our department, a “buffer,” so that the assembly line wasn't “starved.”

The rods would sit on racks, waiting to be consumed by the assembly line a few hundred yards away.

If we had enough rods on hand, everything was fine. We'd pretty much be left alone – me, the process engineer, the hourly workers, the “team coordinator,” etc.

In this plant, “Team Coordinator” was a new term given to what used to be called a “Foreman.” There was a different title because our factory had a slightly different union contract, under a well-intended “Livonia Philosophy,” which was essentially the Deming Philosophy… except we didn't really practice it anymore and the philosophy was ironically just a bunch of posters and slogans that remained.

The “Team Coordinator” title was supposed to imply a number of things. Namely, that the department was supposed to be a team and the Foreman, I mean TC, was supposed to, I don't know, coordinate somehow.

Nobody really ever got that memo. The Foremen weren't trained to coordinate. They had no interest in that. Their old behaviors and old habits (which I remember as including a lot of chewing tobacco, drinking coffee, and yelling) remained even though the job title had changed.

Now, if we did NOT have enough inventory… then all hell broke loose. If our connecting rod machining equipment broke down and production stopped, our inventory would get depleted. As it got progressively worse, the Area Manager (the Foreman's boss) and the Plant Superintendent (the Area Manager's boss… he reported to the Plant Manager) would show up and start scowling, tapping their feet, and crossing their arms, as if that helped.

We'd get a lot of attention if we were in danger of stopping engine production… well, unless, say, the cylinder head department was having more trouble than us… if we were having a bad week, there was nothing like hoping and praying that another department would save you by doing worse.

Adventures in Bad Leadership & Bad Hair

If our inventory ran out completely, the yelling (now, with more cursing!) would really start. The Area Manager (who they never tried renaming to “Area Coordinator”) would stand there, mainly looking nervous because he was about to get yelled at. Bob, the Plant Superintendent (not a “Plant Coordinator”) would yell and scream and spit and curse (there was A LOT of cursing, even on the good days). He's be making such a ruckus that you'd almost swear his bad toupeé (almost this bad) would fall off. Sadly, it never did. It would have made for a priceless picture, but, again, we didn't have cameras with us in our pockets back in those days.

We had to laugh at what we could… and that include Bob's bad toupeé. The color of the rug never matched the color of the real hair that still existed on the back of his head. Letting Bob walk around like that was just one example of the organization not pulling the “andon cord” to point out an obvious problem.

Running Low on Inventory

With all of that buildup, here's what happened that led to my actions that might have gotten me fired. The primary problem that mattered was running out of parts and shutting down production.

This incident occurred maybe 10 months into my two-year tenure at GM. Later, in my second year, we thankfully got who I'll simplistically call the Good Plant Manager. This incident was near the end of the regime of the preceding “Bad Plant Manager,” before he got promoted (put out to pasture) into a job at Powertrain headquarters… after a quality catastrophe that occurred soon after this incident. I was pretty miserable. I was thinking seriously about leaving for grad school or maybe just quitting my job and joining the circus.

On this one day, the connecting rod line had a lot of machines broken down and was really messed up. I think things had gotten so bad that we had interrupted engine assembly and they were threatening to interrupt Cadillac car production. This, when it happened, was a VERY expensive event because GM counted every 50 seconds of downtime as a lost sale and lost profit (keep in mind Cadillac was still the “Cadillac of Luxury Cars” at that point and had relatively high sales, even if their customer base was aging quickly and dying off). As current CEO Mary Barra admits today, it was more of a “cost culture” than a “quality culture” that point.

It was tense. There was a lot of yelling and blaming, most of it directed toward the Foreman, maintenance managers and skilled tradesmen, and the hourly workers. I guess the industrial engineer wasn't expected to do much in a situation like this, so I wasn't being blamed. I could have run some calculations (or run a computer simulation) to show that our buffer should have been higher, given our frequent machine downtime and production variation, but that would have not been welcome input, nor would it have been helpful at that point. Unlike later in this story, I kept my mouth shut.

“Fallen Soldiers”

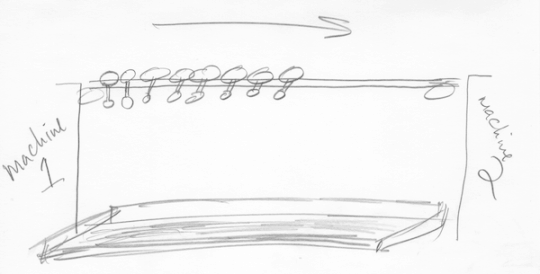

I can't find a good picture, but the connecting rods moved along from machine to machine on long rails that lurched forward, backward, and then forward again in a single piece… so the connecting rods would “march” or hop along, burping forward an inch at a time toward the next machine. The rails also held “work in process” (WIP) between each machine, so if one machine broke down, the whole system didn't stop because WIP would be consumed from the preceding rail.

When a WIP rail was full, the rods would butt up against each other real close. The picture below somewhat shows how they'd press against each other (ignore the one rod laying across the top):

The drawing below is my terrible and lazy attempt to try to draw out what this looked like as they soldiered on between machines.

In the bottom of the drawing (boy, the drawing requires a thousand words to decipher) is what we called a “Drip Pan” (not a “Drip Coordinator”).

The parts were, with no offense meant to them, greasy. By that, I mean they dripped grease, even on a good day. The drip pan generally caught said grease (somebody was happy to do their job!) and prevented it from joining the rest of the grease that was normally on the floor from other sources, known and unknown. I should have drawn some floor grease. You'll have to imagine the floor grease and imagine me falling down in it and hitting the floor, as I did once (without creating a lost work time injury). OSHA reportable? Sure. Reported? Nope.

Anyway, I believe it must have been against UAW rules to clean out the drip pan or something. The “Drip Pan Coordinator” role had been negotiated away in the last contract… OK, I made that up. But, the pans were full and nasty (like Bob, after lunch). A few years worth of grease had accumulated and who knows what microbes were living and mutating down there in the pit.

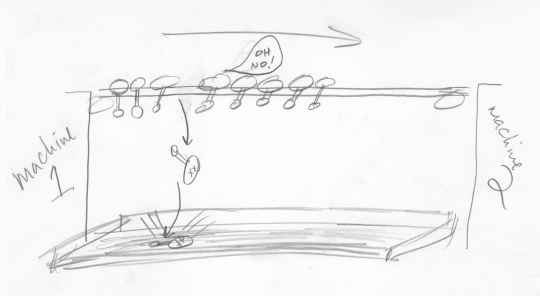

The workers were miserable. The equipment was uncooperative. To the best of my knowledge, the parts were not sentient… but some of the rods apparently couldn't face the idea of being in one of our engines. Every so often, a few of the rods would get pinched together on the conveyor rail and one rod would basically pop up off the rails and take a sad plunge down into the depths of the drip pan, as pictured below:

There were a bunch of fallen rods living (and probably mutating) down in the Drip Pan. Some had been there for years in that filthy muck.

Digging for Gold, er, Greasy Rods

So, anyway, you remember me mentioning that inventory was low. The inventory racks for the finished rods were empty. The last machine in the line was still running, so the Foreman and others were pressuring the workers to put all of the WIP through that last machine so we'd at least have something in inventory. It would delay the yelling and cursing for a bit, at least.

I distinctly remember seeing one of the hourly workers reaching into the Drip Pan muck (ew, no gloves!) and pulling out what looked like rods.

I asked, “What are you doing, Rodney?”

Rodney said, “Scott told us to find all the parts we could find down here.”

“To do what?,” I asked.

“To run 'em through the machine,” said Rodney, being a cooperative southern gentleman, who generally did, with a smile, what the Foreman asked him to do.

Now, I was just an industrial engineer, but this seemed like a REALLY bad idea to me. The rods were likely dinged up from their plunge down into the muck and the hard surface at the bottom (or from hitting other fallen rods). I'm pretty sure the formal quality plan didn't say it was OK to wipe off fallen rods and then run them through the machine.

It was really late in the day (into second shift, I think) and I don't think the Quality Manager was around.

I asked the Foreman about this and he just glared at me with the look of a guy who had been yelled at way too much that day and was just itching to take it out on somebody else (and/or he just really needed a cigarette). Scott always needed a cigarette.

I went to the Area Manager and said, “Hey, I don't think we're supposed to be doing this. Some of those rods seriously look like the last model from a few years ago, they aren't even the same.” The shell-shocked manager (let's call him “HBS”) stammered something about having to make the production numbers and to build inventory back up.

“Quality is Job One,” was Ford's slogan at the time. GM's slogan was basically “Quantity is Job One.” Move the metal. Make the numbers. Ship it!

I was getting nowhere in my pleas for quality there at GM. I was trying to put the customer fist. Part of me said, “Hey relax, if they are the wrong rods, they won't fit into the engine and the assembly line will see that.” Oops, I was getting infected a bit with that GM way thinking.

My Conundrum and My Messy Choice

I had a choice… did I speak up and complain about some of these rods possibly being dinged or damaged (the ones that were the correct model year) or did I just keep quiet? If the parts fit into an engine, but were damaged and that was being covered up (or not investigated), would that cause problems for a customer in the engine of their new Cadillac? We all received a weekly voice mail message with the field service incident reports that informed us about engines that failed in brand new cars. This was happening far too often and our quality reputation couldn't take any more hits, given the previous two decades of GM production.

Feeling like I didn't really care if I had this job anymore, I decided to speak up. I decided to put the quality and the customer first. Why not? What did I have to lose?

I decided to walk over to the main office area (which was pretty far from the shop floor, of course) to talk to my boss Sid, the Industrial Engineering Manager (and one of the really nice, thoughtful people working there).

When I told him what was happening, I was pretty frustrated and was spitting out random words, shouting, “Muck pit… rods fell… wiping off… back into the machine… wrong year???,” I don't think I was making a lot of sense. He sort of gave me a resigned shrug and implied it wasn't my problem to worry about.

Youthful Petulance & Splattering Grease

In a fit of youthful petulance, I stomped back out (being careful not to slip and fall in the normal, everyday floor grease) to the connecting rod area. I reached into the muck (ew, no gloves) and grabbed one of these fallen rods.

I stomped (again, careful, safety first) back to my manager's office. I was dripping grease all over the place (well, I was probably sweating and the rod was dripping grease). None of this was an issue until I was back into the carpeted office area (which, to their credit, were not normally greasy).

I walked into Sid's office and slammed the greasy connecting rod down on his desk, splattering grease onto some papers that were scattered about.

“Oh crap…. this might get me fired,” I thought. I swallowed and asked Sid, “Would you put this into car? Really? Would you sell that?”

To his credit, Sid looked at me… looked down at the part… looked over at the grease spatter and said, “Let me make a call.” I figured I had done all I could and I stomped out into the afternoon darkness to go home.

The next day, I got a bit of grief for not cleaning up the grease, but I learned that somebody had intervened and made it clear to the Area Manager and Foreman that any parts that had fallen into the muck could not be cleaned up and used.

I heard some lame, muttered rationalizations about how “we wouldn't have really used those, anyway.” But it sure sounded like they were going to try. What would have happened if I hadn't made a fuss? What would have happened to those connecting rods? To those engines? To those Cadillacs? To those customers?

I really hope the “new GM” has really put the “old GM” ways behind them… their customers (and their remaining employees) deserve it. I hope the new GM isn't putting their hourly workers, engineers, and managers into a bad position where they can't really put the customer and quality first.

Please scroll down (or click) to post a comment. Connect with me on LinkedIn.

Let’s work together to build a culture of continuous improvement and psychological safety. If you're a leader looking to create lasting change—not just projects—I help organizations:

- Engage people at all levels in sustainable improvement

- Shift from fear of mistakes to learning from them

- Apply Lean thinking in practical, people-centered ways

Interested in coaching or a keynote talk? Let’s start a conversation.

![When Was the Last Time a Leader Around You Admitted They Were Wrong? [Poll]](https://www.leanblog.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/07/Lean-Blog-Post-Cover-Image-2025-07-01T212509.843-238x178.jpg)

[…] See on http://www.leanblog.org […]

Comment from Linkedin:

Yes, I’m definitely thankful for the lessons learned during my time at GM. That includes both my first year where things were very messed up AND my second year where we had better leadership and things started to improve.

Mark – great personal story. Unfortunately, your story is all-too-common and I’m sure many reading your story can relate to it, regardless of industry or even function. The overall tone of gloom and feeling like a cog is the norm in workplaces these days.

Great story and thanks for sharing it.

I’m personally very lucky that I haven’t had that gloomy “I’m just a cog” feeling in a long time.

But, I realize that many people working in hospitals have that feeling and I know how much it sucks. That’s why we’re trying to change things.

Well done Mark! What a great story. It has made you what you are today!

I can’t verify the story or not, but years ago, one of the car magazines had a reader write in and tell about his own Cadillac experience. It seems he had a rattle that wouldn’t go away in a door. The dealer eventually pulled the door panel off and found a coke bottle with a note to the effect of “hope you’re having a nice day you rich s.o.b”.

Actually, Cadillac is making some nice cars these days. A few years ago, their CTSV model set the fastest time of any production 4-door car around the Nurburgring. Let’s hope things have changed. Is the Livonia plant still around?

There are many many stories of workers sabotaging cars on the GM assembly lines. I’d never heard of a note like that. I think it’s important to ask why and how the culture in the company got to be so corrosive. I’m certain no UAW worker would have ever done anything that bad on their first day at work. How do people get to be like that over time? Being in a bad culture can really warp even the best people.

Many of the assembly workers at our plant drove Cadillacs, actually. They were paid well and got a nice employee discount. Was the electrician who made $100,000 thanks to lots of overtime a “rich SOB”? Maybe.

No, the Livonia plant is now closed – it was closed down during the GM bankruptcy a few years ago. The sign with the missing GM logo… that picture was taken after the plant closed.

When I worked at GM/Delco Electronics in Kokomo, IN, a similar thing happened. We had a batch of radios that had failed statistical end-of-line testing, and were in the QC quarantine “area” (locked, chain link fenced area). Weeellll, the third shift was way short on making quota one night, and it became obvious they were not going to make it. The shift supervisor had a millwright grab a pair of bolt cutters, cut the lock, and ship the entire contents of the QC quarantine area! Next day, Lansing assembly is screaming bloody murder, since every other car’s radio does not work.

You would think the 3rd shift supervisor would get fired? Nah, got a bonus for “quick thinking resulting in making shipment on time….”

They should have burned the RenCen to the ground……

It scares me to death to think that kind of defective management is now running our hospitals. Yet, now that the US Gov’t has injected itself directly into all of healthcare, it does not surprise me at all…….

Thanks for your story, Steve. It doesn’t surprise me that “making the numbers” (quantity) was the primary goal there, not quality.

Now… as to “defective” management thinking in healthcare (quantity over quality)… that was present LONG before the government got involved.

[…] hit their daily production goals. At the old GM, quantity was quite often prioritized over quality (as I wrote about here). At Toyota (and I’d presume at the new GM), safety and quality don’t take a backseat […]

I to worked at Livonia Power train from 1994 to the end in security. and saw things from that side and knew a lot of

the workers Uaw and none. I liked all of the people I knew and worked with. One fact I know of was the rows of intake

manifolds made by focus hope placed in back of waste treatment they were all new and scrap they were made wrong

as I remember. I all so got to follow a North Star laden gondola to the scrap yard witness and document the

destruction of the North Stars. I think the v8,s had a noise problem.