I wrote an article for LinkedIn yesterday about the recent GM ignition problem controversy and recall. I commented mainly on the video put out by new CEO Mary Barra (which I encourage you to watch).

As a former GM employee, I reacted (at a gut level) to a few things in the video. The main thing was her admonition that, basically, quality is everybody's job and that everybody needs to put the customer first.

If I still worked there, I'd find that offensive. When I was an entry-level Industrial Engineer at GM, my default was to put employee safety and customer quality first. That wasn't always well received, to say the least. I shared one of those stories in the article and I might share more here.

As Dr. Deming taught, quality begins in the boardroom. If Barra thinks she has to remind the employees to put the customer first, maybe she and the board should look in the mirror and think about their role. It's hard for individuals to do quality work when the culture (management's responsibility) gets in the way.

You can read my article here. Or the full text is below. Feel free to comment here (for a Lean audience) or on LinkedIn (for a more general business audience), depending on what you'd like to say.

Thanks for reading!

The Article:

If you, the reader, ever started a small business, I'll give you the credit that you'd start off with a passion for your customers, whether this means delivering a product, a service, or an app that solves a problem for them and delights them in some way. Without customers, we have no business. In the early days of the auto industry, Henry Ford realized this in 1914 when he wrote:

…for of course it is not the employer who pays wages. He only handles the money. It is the product that pays the wages.”

And, of course, the money ultimately comes from the customer… a satisfied customer, something Ford paid attention to for the entire life of a car:

A manufacturer is not through with his customer when a sale is completed. He has then only started with his customer. In the case of an automobile the sale of the machine is only something in the nature of an introduction.”

But, 100 years later, far too many large companies somehow manage to lose sight of the customer and get more focused on internal matters and their finances. The same thing happens, unfortunately, at many hospitals and healthcare institutions.

GM, Quality, and the Customer

I grew up near Detroit, I worked for GM in the mid 90s, and I still root for the company. I have also been rooting for their new CEO, Mary Barra, not because she's a woman (an important first for the industry), but because she's an engineer and a “car guy” (as the legendary Bob Lutz dubbed her). For better or for worse, she has worked there her entire career, since 1980.

In the midst of the current controversy and GM's recalls over faulty ignition switches (and the 12 to 303 deaths that are alleged to be a result), Barra put out a video statement to employees that was also released to the public.

In the video, Barra says, in part:

We need to continue on the path of putting the customer first in everything we do. It's not something that only gets decided by senior leadership. We all have to own it.”

It's a shame when leaders feel they have to remind their employees that the customer comes first. Do the world's best companies really have to do this? Do leaders in the world's best companies (or even a local small business) think their employees have forgotten this?

Hospital leaders have been doing the same thing in recent years, talking about and promoting a seemingly new-found discovery that “patient-centered care” is important. Now that I work in healthcare, friends of mine from other industries often ask, quizzingly, “What else would healthcare be, if not patient centered? Why are they bragging about that?” Of course, the nurses and other front-line staff never forgot that healthcare is about the patients… but many executives have.

To their credit, hospitals are using Lean and other methodologies to truly put the patient first, instead of designing things around the needs and preferences of physicians or the hospital.

To her credit, Barra is talking about putting the customer first. But why wasn't that happening? Are they really “continuing to” put the customer first or merely “starting to?”

Barra says “we all have to own” putting the customer first, meaning all employees. Tell that to the GM engineer who warned about these “flimsy” ignition switches back in 2001 before anybody got hurt. Was the customer put first? If not, whose responsibility is that?

Where Does Quality Start?

The late great Dr. W. Edwards Deming famously said, “Quality starts in the board room,” with the policies and decisions of the company's most senior leaders. Can we hold employees accountable for quality when the culture doesn't allow for quality and the customer to be a priority? Dr. Deming would say, “Hold everybody accountable? Ridiculous!”

Barra can remind employees all she wants, but chances are the engineers and front-line employees of GM never forgot that quality and the customer come first.

When I worked at GM, I continually saw my factory's top management make decisions that directly undermined quality. Pick on the UAW all you want, but most of the UAW workers wanted to put quality first and management wouldn't let them. It was as simple as that.

In just one very specific example, the operators in the engine block machining line were supposed to, per the engineered and agreed upon “process control plan,” stop the line to check the critical dimensions of an engine block every hour or so. When production was behind schedule, and it often was, managers told the workers to let the machine keep cranking out parts without workers doing the proper checks. Management decided to put production numbers (quantity) over quality.

And, when there were many quality problems (such bad engines being discovered at the end of the car assembly line or, even worse, reaching a customer), management had the nerve to blame the workers in written memos that were distributed throughout the plant.

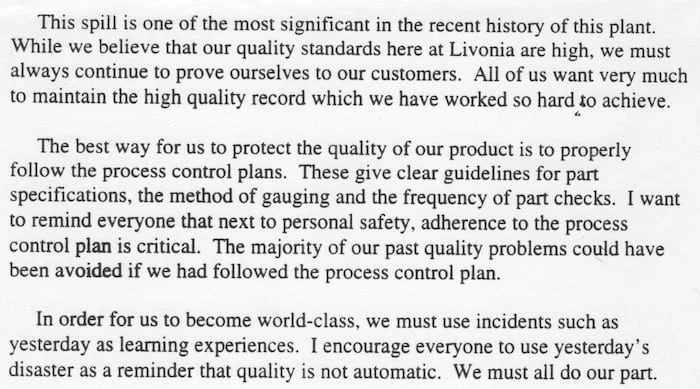

Part of that memo from 1996 reads (yes, I kept a copy):

“All of us.”

“We must all do our part.”

These are empty words.

Management said in the memo, “adherence to the process control plan is critical,” when the guy who wrote the memo was often the one refusing to let workers stop the line. Management wasn't allowing workers to follow the process control plan, yet they blamed the workers… repeatedly. Ridiculous!

The author of the memo wasn't stupid, so he must have seen the irony in this… but he couldn't admit responsibility in the “Old GM.” He had to blame the workers.

Marry Barra and other manufacturing CEOs say, “We all have to put the customer first.” The employees likely say, “Yeah, we know. Please let us.”

The hospital CEO says, “We all have to put the patient at the center of everything we do.” The nurses roll their eyes and say, “We know. Please let us.”

GM can talk all they want about the customer coming first. But, old habits die hard. Is the “New GM” really different than the “Old GM?” I certainly hope so.

Are they putting the customer first? Are you and your organization? Who needs reminding about quality and the customer – the workers or your senior leaders?

What do you think? Please scroll down (or click) to post a comment. Or please share the post with your thoughts on LinkedIn – and follow me or connect with me there.

Did you like this post? Make sure you don't miss a post or podcast — Subscribe to get notified about posts via email daily or weekly.

Check out my latest book, The Mistakes That Make Us: Cultivating a Culture of Learning and Innovation:

“If Barra thinks she has to remind the employees to put the customer first, maybe she and the board should look in the mirror and think about their role.”

Not uncommon to find execs who created or were part of the problem admonish others for the problem.

John Chambers, CEO of Cisco, whose failed experiment with a new management structure ca. 2009-2011 resulted in a reversal in which he told employees in a letter dated 4 April 2011: “…we have disappointed our investors and we have confused our employees. Bottom line, we have lost some of the credibility that is foundational to Cisco’s success..”

In all three instances, “We” actually means John.

Great example, Bob. Ah, the royal “we.”

Reminds me of the CMO of Cedars-Sinai beating his chest after the Quaid twins were overdosed with heparin. He said:

I’m quite certain that procedures were not be followed all the time, not just that unlucky day for the Quaid twins. That’s a system problem.

Who is responsible for “the system?” Management. But, they rarely take responsibility.

Who should have been ensuring that procedures were being followed? That they *could* be followed in a chaotic workplace? Management, including the CMO and other Chiefs.

There’s more evidence of top-down blaming here.

What keeps a hospital CEO up at night? I’d like to think that the poor quality and patient harm would keep a CEO up at night above all else. There are so many risks and so much patient harm, I wouldn’t be able to sleep.

There’s a comment in the piece:

This sounds like blaming the nurses and doctors. Why aren’t they following best practices? Do they not know about them? Do they not have the time to do the properly? Are hand gel or foam dispensers empty (as I often find them)?

This is a system problem that can’t just be dumped on nurses and doctors. Everyone needs to work together to solve it… but leadership is responsible for creating the culture and systems that make it possible.

Yes, senior leaders can get insulated in the administrative suite. A former CEO in an organization I have just become familiar with lectures accross the country on the concept of patient first, accountability, and mutual respect. My own experience is that the senior leaders in this organization sincerely demonstrate these values to a high degree amongst themselves. On the other hand, there are areas of the organization where patient focus in trumped by expediency, mutual and downward respect is demonstrably lacking and there is an almost total absence of accountability. Unfortunately, it took an outside consultant to point out the reality of all this. Things are changing but it is difficult to stop 25 years of polishing the false facade and get your hands dirty.

Three pairs of Nike Michael Jordan shoes fell apart on NBA players. Jordan himself called to apologize (well, called an agent).

In healthcare, studies show that after a medical error, if the MD is honest and apologizes, they are less likely to get sued by a patient or family.

I wonder if Mary Barra or Akio Toyoda personally call the family members who die in accidents caused by defective products (or Alan Mulally from Ford). If so, would it be a sincere apology or an attempt at positive public relations?

What would you do? Would you call the families?

I read today that Barra and GM created a new job in response to the ignition switch crisis…

link

Does that impress the public that they’ve created a new job for a GM lifer who is supposed to be responsible for global vehicle safety?

I was impressed with her common sense about earlier changing the GM dress code policy from ten pages to two words:

“dress appropriately“

In this column in USA Today, the columnist praises Barra for taking ownership of the problem.

link

He writes, of CEOs in general:

So maybe she isn’t just blaming employees or blaming others.

100% agree. There is a huge disconnect between the Corporate level and the worker level. It seems every time there is an accident/recall/issue, the first response is to blame the culture or add additional steps to ensure policies and procedures are being followed by everyone. No one takes the time to identify the reason why employees quit following the policies or procedures. While I am fairly new to the LEAN game…I never implement anything until I understand the root cause. This has concept has served me well in the military and now the healthcare industry. An employees attitude and performance are a direct reflection of their leadership.

Quality never takes a day off!

Thanks for your comment, Vernon.

That’s the right question… to understand why processes aren’t being followed.

I’ve worked with a retired military medicine leader who would ask the civilian hospital lab staff where he now worked if there are legitimate barriers to doing your work the right way. Is it a situation where people truly CAN’T do the right work the right way or is it their choice, as in they WON’T follow the procedures or standardized work.

More often than not, it turns out to be a system issue… such as being overburdened or being under pressure to hit unrealistic production targets, etc.

Leaders often need to look in the mirror at their own policies or decisions instead of just blaming workers… I think that’s what really helps spur improvement.