Out there in the Lean and quality improvement communities, you sometimes hear some silly things. Sometimes, I want to attach the “Lean As Mistakenly Explained” (or L.A.M.E.) label to what's said when it really seems off the mark from what Lean is really all about. Davis Balestracci, a columnist for Quality Digest, passed along something he heard from a “Lean guru” (whatever that means):

“In my opinion, any approach should also involve the use of data in some way, shape, or form. I once had a lean sensei (local “guru”?) vehemently make the point that lean does not involve data at all.”

What?? Read his entire column here. I asked Davis, in a comment, if he had misunderstood the speaker. I was trying to give the speaker the benefit of the doubt, given the oft-repeated quote from Toyota's Taiichi Ohno:

“Data is, of course, important in manufacturing,” Ohno often remarked, “but I place greatest emphasis on facts.”

Ohno wasn't saying to ignore data. He was saying to not rely on reports – today, that would be spreadsheets and “dashboards.” Reports and data can be skewed (intentionally or inadvertantly). Ohno was saying we have to go to the Gemba (get out of the office) and see what can be verified with our own eyes. I've never heard anybody say that data isn't important in Lean.

I *have* heard Six Sigma people say, incorrectly, that Lean is just qualitative and Six Sigma is the only “data-driven” methodology. That's false.

I was taught to use data in Lean improvement work and that's certainly the message sent by Toyota – to use data (and statistics!) when appropriate and helpful. Not everything can be quantified (a key Deming principle), but we certainly look for data and measures where we can, rather than relying on feelings and opinions. Did patient satisfaction improve? “I feel like it did.”

Wait – how do we know that it improved? Do we have data that back up that claim? I recently found a Toyota publication that was (probably somewhat sketchily) shared on a Chinese website. It says, in part (drawing on Masaaki Imai and his book KAIZEN, which is cited in footnotes): The principles of Kaizen are:

- the most important company assets are the people

- evolution of processes will occur by gradual improvement rather than radical changes

- beneficial changes are to be implemented immediately where possible

- improvement recommendations must be based on statistical and quantitative evaluation of processes

I don't know who is running around saying “data doesn't matter” in Lean (unless it's, like I might suspect, a “Lean Sigma” person who learned some sort of claptrap about Lean not being “data-driven,” instead of somebody who has learned directly from Toyota and its people). You can't fault individuals if they've been taught badly (even if that person is a professor).

Related post from 2013:

Does Toyota think data should be involved? More evidence, from the document:

“The Check is the measurement of the Do. This means that the countermeasures implemented must be measurable. If they are not, there has been a failure in the planning section. As is understood, if you can not measure it, it is not worth doing.”

Here is a point where Toyota strays from what Dr. Deming taught them about things being measurable:

“… the most important figures that one needs for management are unknown or unknowable (Lloyd S. Nelson, director of statistical methods for the Nashua corporation), but successful management must nevertheless take account of them.”

That's an interesting divergence of thought. those two equally valid opinions or a difference between right and wrong? Is it possible to prove or disprove either statement (“if you can not measure it…” or “the most important figures… are unknown or unknowable…”)? Seems like two different opinions. I'd align myself with Dr. Deming, based on my own experiences.

Does “Plan Do Study Adjust” Jump to Solutions?

I also hear some loud voices that say PDSA (Plan – Do – Study – Adjust) is a flawed model because it supposedly starts with the “Plan” to implement a certain solution. That is, of course, hogwash and you realize it as such if you've been taught or mentored on PDSA/PDCA from a Toyota person.I've been lucky to have that sort of coaching. And, that information is available in books, too.

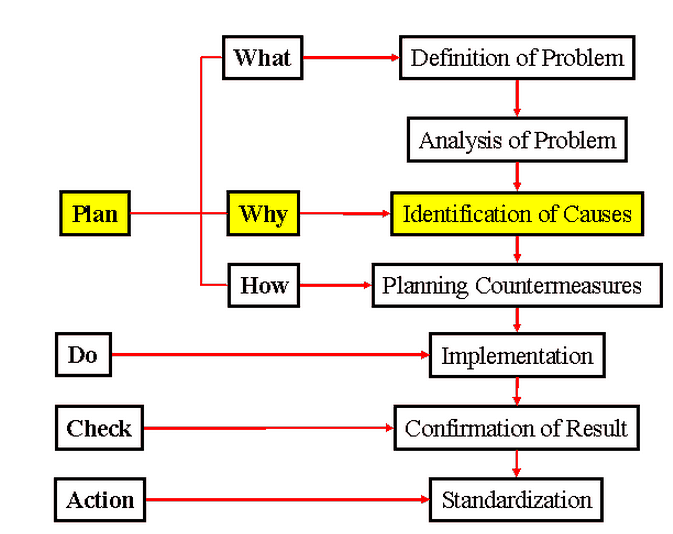

“Plan” actually begins with studying and understanding your system and the problem. We have to, in “Plan” properly define a problem so we can then understand causes and root causes… long before every thinking about countermeasures to test in the “Do” phase of PDSA. Here's a diagram from that same Toyota publication:

What is “Plan,” according to Toyota? Define the problem, analyze the problem, identify causes, AND plan countermeasures. There is no “jumping to solutions” in this approach. You see the same thing in the Toyota “8-step problem solving model” and its mapping to PDSA (and its mapping to the Six Sigma DMAIC model) from the “Kaizen Factory” website.

So, if you ever hear these statements:

- Lean is not about data

- Lean would say “kick the patient out of the room because their time is up“)

- PDSA says jump to a solution without first studying the problem

I think you can definitively say, “WRONG!”

Sometimes, we have different opinions… and that's OK. Sometimes, things are factually incorrect.

Please scroll down (or click) to post a comment. Connect with me on LinkedIn.

Let’s work together to build a culture of continuous improvement and psychological safety. If you're a leader looking to create lasting change—not just projects—I help organizations:

- Engage people at all levels in sustainable improvement

- Shift from fear of mistakes to learning from them

- Apply Lean thinking in practical, people-centered ways

Interested in coaching or a keynote talk? Let’s start a conversation.

Mark,

Nice post. As regards the words in PDCA/PDSA (I prefer Study over Check) I don’t think that the model is flawed, in fact the opposite, but I do think that the words: Plan, Do, Study, Act are misleading. People hear “Plan” and they think “project plan” and they spend weeks or months planning a change. They hear “Do” and that sounds like “enact the plan”, as in implement it as if it were the solution. They hear Study but frankly they have all ready planned and done for months and they haven’t got time for any studying and it doesn’t get done. And “Act”? What’s the difference between that and Do? We already did the Act in Do!

My reformulation is HELP: Hypothesis, Experiment, Learn, Put into Practice. I think that takes it back closer to the scientific method that PDSA is based upon and my experience is that people understand it better. They get that Hypothesis is an idea to be tested, it is explicit that Experiment is something that tests the idea, Learning is easier since by design, the experiment is small enough to learn from and Put into Practice is self-evident (of course depending upon what you Learn, you may decide not to put anything into practice).

After a little bit of feedback I am toying with changing the H from “Hypothesis” to “Have an Idea”. What do you think?

Hi Rob-

Thanks for your comment. I have also shifted to using PDSA generally… “check” runs the risk of sounding like “confirm you got the results you predicted” as opposed to an open and honest evaluation of the test.

You’re right that “Plan” and “Do” can get misinterpreted.

I’ve sometimes wondered if Plan-Test-Study-Adjust wouldn’t be better terminology.

HELP is an interesting framework. I would prefer “Hypothesis” because that sounds more like a test. “Have an Idea” sounds like jumping to a solution.

That’s why, in Kaizen, I emphasize identifying a problem AND having and idea. See this template for that structure… this card is meant to model PDSA.

PDSA is most definitely not a jump-to-solutions approach. Not only does an individual PDSA cycle include the analysis steps that Mark mentioned in the Plan phase, but if we zoom out to see an individual PDSA cycle as one small step in a larger improvement cycle (i.e. the Improvement Kata), then we see that additional planning/analysis precedes the use of PDSA. This pre-PDSA planning/analysis ensures that we understand the bigger systemic issues prior to launching PDSA to address process-level issues, and is further evidence that PDSA is not a jump to solutions approach.

Furthermore, when PDSA is utilized properly as a means of hypothesis testing, then even if we bypassed all the planning/analysis steps (not advisable, but in the real-world this happens) we would still not be jumping to solutions because we would be completely willing to revise our hypothesis based on the evidence (i.e. modify the countermeasure or choose another one to test). In other words, it’s not jumping to solutions if you’re just testing potential countermeasures. One might say that this is an inefficient approach, but that ignores the incredible value of the learning that is produced through multiple cycles of hypothesis testing.

At the 2014 Lean Transformation Summit, there’s a presentation about Toyota (the TSSC) helping the Food Bank for NYC.

They all made it clear that data was important… looking at measures was a key way of figuring out if you have improved.

But, of course, it wasn’t all about measures… it was also about provide the right service in the most dignified way.

See my notes:

[…] a great guest post by Karen on Mark Graban’s blog about PDSA vs. PDCA, and another spirited post by Mark himself on the […]