tl;dr: The article explores the compatibility between Lean methodology, Deming's principles, and modern accountability frameworks. It argues for an integrated approach that emphasizes systemic improvement, continuous learning, and a culture that moves away from blame, thereby uniting these philosophies more effectively.

Today, I'm spending the day with a health system and their quarterly management retreat, which includes about 200 managers from the C-level on down.

One of our topics, prompted by some feedback from a management survey, is accountability. This is a really rich and interesting topic and I will barely scratch the surface on it in this post, but I wanted to share some thoughts from my preparation for the discussion and to get your comments, as well.

When I hear leaders say, “We need to hold our employees accountable!,” I usually have to ask, “So, what, specifically do you mean by that? Give me an example and a scenario.”

Far too often, “accountability” means “blame” and finger pointing – and I don't think that's really accountability in a Lean management system context.

One dictionary definition of accountability talks about the obligation or willingness to accept responsibility:

Accountability is something you take on voluntarily… it can't be forced on you. You can choose to be accountable. How can leaders create an environment where people CAN be accountable?

A dictionary definition of responsibility talks about “the person who caused something to happen.”

There are many cases where people are “held accountable” (having this accountability forced on them) when it's unfair because they aren't at all responsible for what happened.

Let's say a senior leader sees a nurse go into a patient room without using foam cleanser on their hands. “Let's hold them accountable!”

As Dr. Deming said, this is “ridiculous!”

Dr. Deming said, “Fix the processes, not the people.” Great advice.

Deming wrote (in The Essential Deming, a great read):

“The boost in morale, and in production as well, of the production worker in America, if he were to perceive a genuine attempt on the part of management to improve the system and to hold the production worker responsible for only what the production worker is responsible and can govern, and not for handicaps placed on him by the system, would be hard to overestimate.”

This statement applies to healthcare professionals, not just “production workers.”

Can we hold nurses and other staff accountable for not always following proper hand hygiene procedures when coming in and out of patient rooms?

Let's say the foam canisters are empty outside a few rooms in a row (something I've seen recently). We can't hold the nurses accountable. This is a system problem. “Writing up” or punishing the nurses would be counterproductive. We need to ask why the canisters are empty? Is there somebody to hold accountable for not restocking the canisters? Maybe not – what if it's a bad process, where there's no “standardized work” and no clear cut assignment of who refills the canisters (“everybody?”).

Are we more willing to “hold accountable” a surgeon who chooses to not follow the supposed “universal protocol” timeout procedures before a case? This might be a CHOICE on the surgeon's part… they are probably more solely responsible than the nurse who didn't disinfect their hands. But, there might be extenuating circumstances for the surgeon even. Before we jump to blame, we have to ask, “Why wasn't the protocol followed?”

We can ask:

- Is it a case where the person CAN'T do the work properly?

- Do they not know how? This might be a systemic training problem. The individual can't be held accountable for that.

- Does the person not have the right resources? Maybe they WANT to do it right, but they just can't. Leadership needs to help eliminate those barriers.

- Is it a case where the person WON'T do the work properly?

- Is the situation one where the person truly has a choice and they made a bad choice?

As Dr. Robert Wachter has written about so well, not leaping to blame and punishment doesn't mean we NEVER hold people accountable.

David Marx writes, in the context of the “Just Culture” methodology:

“No one can afford to offer a ‘blame-free system' in which any conduct can be reported with impunity—as society rightly requires that some actions warrant disciplinary or enforcement action. It is the balancing of the need to learn from our mistakes and the need to take disciplinary action (that must be addressed).”

As Wachter says, we have to find balance.

This “Incident Decision Tree” flowchart (PDF), developed in the NHS, provides some good guidelines, I think. It very often leads to a conclusion that the accountability rests with the system (the responsibility of management) not the individual.

One other thought that comes up in these discussions of accountability is that senior leaders are often trying to leap to hold front-line staff accountable for their actions. But, front-line leaders are pretty far removed from the actual work and their actions might just be tampering or interference.

I'd suggest that senior leaders should focus on creating a culture of accountability through their own actions:

- C-level executives demonstrate the right behaviors (always, and I mean ALWAYS, following hand hygiene protocols when entering a unit or a room)

- C-level executives can hold VPs accountable for behaviors (which includes learning how to remove barriers and look at systemic factors)

- VPs can hold Directors accountable

- Directors can hold Managers accountable

- Managers can hold Staff accountable (working together to solve systemic problems, not just blaming and punishing)

And the accountability goes both ways… leaders have to be accountable (choosing to be accountable) to their employees. There's “mutual accountability” and “tiered accountability” in a Lean culture.

From The Toyota Way Fieldbook:

“I learned you need to keep the [employees] accountable to the plant manager who is accountable for the implementation of the culture shift that we're trying to achieve.”

Without mutual accountability that starts at the top, a CNO might complain that nurses are not doing hourly rounding. Instead of just saying, “Hold them accountable!,” leaders need to work together. Instead of just assuming the rounding will be done, front-line managers can VERIFY that rounding is happening by being out in the workplace and doing checks (and sometimes rounding with a staff member). This can be done in a supportive and collaborative way.

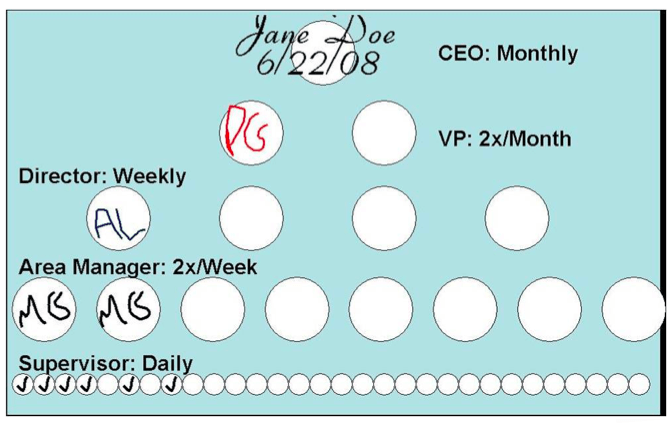

Directors can go and verify as well… and all the way up the chain, as they did in the NHS. Represented in this drawing I made, there's tiered checking of standardized work by all levels in the organization (or there's supposed to be):

In the example, the CEO had visited the unit on the 22nd. She could see from the check boxes that other leaders weren't doing all of the rounding checks (or it wasn't documented). The CEO can go round with others… and ask questions about the rounding checks. Asking questions emphasizes the importance without having to “come down on people.” When managers and directors realize, “This is important enough for the CEO to come ask about it,” then they're more likely to be accountable, if they are able to.

The CEO is demonstrating accountability by being there once a month as the visual plan indicates.

If the CEO isn't doing her monthly checks, the message is loud and clear to the others – that the rounding checks are optional.

When my wife, as a leader, wants her managers to be accountable for not screwing around on their Blackberries during meetings, she leads by setting an example. She leaves her Blackberry in her office. She can then rightfully ask others to be accountable to cultural norms that they pay attention and be present (and I'd admit I'm not always good at that… I need to leave my iPhone in my bag more often).

What does “holding people accountable?” mean in your organization? Is that definition changing over time? What are you learning from your study of Lean principles and Lean management? What else would you add to this discussion?

What do you think? Please scroll down (or click) to post a comment. Or please share the post with your thoughts on LinkedIn – and follow me or connect with me there.

Did you like this post? Make sure you don't miss a post or podcast — Subscribe to get notified about posts via email daily or weekly.

Check out my latest book, The Mistakes That Make Us: Cultivating a Culture of Learning and Innovation:

I forgot to mention that the Wachter article quotes my friend Paul Levy (@paulflevy) from his book “Goal Play”:

Hi Mark,

Great article. I think Paul is one of the only hospital CEO’s I’ve ever seen that understood what Deming taught- holding individuals personally responsible for errors in a complex system/process is ridiculous. Hospital leaders regularly make the fundamental attribution error- blaming the individual and not understanding the impact of the situation, process and system structure.

The other common problem I see with healthcare leaders and accountability is the problem of suboptimization in attempting to improve the value of patient outcomes. Improving the rate of hand hygiene or use of OR timeout protocols without measuring the value-based outcomes for the patient is a leadership failure. When protocols are instituted and followed, but patient outcomes are not improved, the solution is not to work harder at implementing the protocols, it is to recognize that suboptimization is occurring and to be accountable for improving the value of patient outcomes, not just documenting some process measures because they easy to quantify and/or are part of various reporting requirements.

Hi Mark

Great post.

Replacing the word “accountability” with “responsibility” can change mindsets and behaviors. The former tends to be more punitive while the latter has more possibility to be mutual. We tend to get better, less defensive responses to the question “What are your responsibilities as..?” or “What are you responsible for in your role..?” as opposed to “What are you accountable for?”

Responsibility is given and accepted. Accountability is pressed upon others. I accept responsibility while I am held accountable.

Nuances perhaps, but words affect thought, thought affects action, actions create artifacts which in turn create environments that create culture.

Jon

Posted on behalf of Ron Phipps, with his permission:

Unfortunately, too often management uses the punitive version of accountability. As Deming and Just Culture state, the individual is rarely the true root cause (sabotage, negligence, incompetence, etc.). Leaders also too often do not recognize this and do not pursue systematic corrective actions. How many times have we just retrained the one who “did it” instead of determining how the process allowed the user to make the error?

Dictating individual accountability is really “lazy leadership”- driven either by a disregard for the known lack of controls in the process or by an unwillingness to investigate how the systems are allowing the issues to occur, and ensuring that future states can be created by implementing the needed systematic controls (better yet, providing the confidence and resources to empower employees to investigate, etc. themselves).

When leaders want to “hold someone accountable”, they are missing the opportunity to create trust, empowerment and a better process.

Team accountability sounds like a step up, but does that really work? Doesn’t that just provide incentive to not report issues for fear of letting the team down? Also, as the saying goes, if everyone is accountable, no one is.

The need for positive, shared accountability should not be understated. Employees certainly see this reality in finger-pointing situations (“if only the leaders were more aware of the issues, asked for our input, and listened to our ideas…”).

Leaders should not be surprised when this top-down accountability is not well received or does not provide sustainable results. In order for a closed loop system for risk management, corrective action and continuous improvement to thrive, it needs frequent and real feedback from staff.

Changing a culture is not a project, it is much more than that. However, providing an environment of trust (including presence, actions and employee engagement opportunities) through projects can empower people, changing how people feel about their control and impact. This in turn can create a new desired culture with shared accountability.

If you are willing to consider that employees ARE the system and accountability is a mindset not a program, an effective way to frame accountability so everyone lives it is possible. Accountability is a mindset. Treating people as capable, able and accountable is threatening to leaders; it creates not being needed as ‘managers’. “Shared” accountability is dangerous. Total personal accountability on the part of each individual is the solution regardless of position or role in the organization. Role clarity and authority level clarity are vital on-going. Personal accountability is, was, and always will be the difference between an organization that needs lots of system fixes and those that don’t. To deliver high quality, lower costs and a need for fewer people to work around the non-accountable, low performers that need to be managed, personal accountability is the foundation. Want to be lean? Be accountable, individually and collectively. “Being accountable” is answering for the results produced good or bad without fault, blame or guilt.

Yes, accountability is a mindset.

Yes, managers should treat people as capable, able, and willing to be accountable. This should not be threatening to managers if we have a culture, led by senior leaders, that reinforces this consistently (in words and actions).

I don’t see how individuals have accountability when they work in a really bad system. When a nurse is asked to do 80 minutes of work in an hour, they can’t held accountable or responsible for a mistake that occurs when they’re frantic and harried.

So, I don’t really understand what you’re saying, Linda. Are you working from a different definition of “accountability” than the one I posted above? I see where people can accept responsibility for their own actions (are they acting ethically and to the best of their ability) but they can’t be held responsible for the results of a bad process – therefore, they shouldn’t be blamed or faulted as individuals.

Mark,

Great stuff! I posted an extended response on my blog in an attempt to reinterpret your analysis through the language of promise-based management.

http://amielhandelsman.com/accountability-reliable-promises/

I welcome your thoughts here or on my blog

Amiel

Mark – Great post. I especially like the mirror you point back at leaders. Accountability is the last step in a long leadership process, and in a truly lean environment is internally assumed rather than externally imposed. The following elements must proceed before accountability even enters the discussion: defining Expectations (std work), Equipping (provisioning resources and skills training as necessary), Enabling (emotional preparation to own the task), Empowering (delegating both responsibility and authority to complete the task or process), and Embracing (providing support as requested)

A few thoughts –

Yes, words are important, so rather than “hold people accountable” lets use the the verb form, as a question: “How do you account for this?” It’s right out of the “lean handbook” if you do it that way: the manager asks “Help me to understand… ”

Second, another verb form: accounting. Visual accounting in the workplace allows for constructive accountability. If we do a good job with visual controls, visual tracking of activities and performance, and visual workplace in general, we have a foundation for a daily or ongoing accountability process that is not about blame, but simply about “how are we doing?” or “where are we departing from the standard?” or “where can we improve?”

Finally, on the topic of mutual accountability, I really appreciate the teaching of Patrick Lencioni’s “Five Dysfunctions of a Team”. Mutual accountability can only occur when we have made unambiguous commitments to which we then can hold one another accountable. We can only reach clear commitments if we have aired (and sufficiently worked through) the relevant conflicts. We can only do that effectively if we have trust in one another (no fear). The flip-side, dysfunctions 1 – 4, read like this: No trust means fear and conflict avoidance. Unaddressed conflict leads to ambiguity of intention and commitment. Lacking clear commitments, there is no basis for mutual accountability. A key distinction is that commitments are made by the individual accountable, so they set the bar: “Here’s what I’m going to do!” It strikes me as highly consistent with Deming’s teaching and a workplace culture of respect for people.

Great post and comments.

It seems most managers talk about accountability, but few have an accountability process. David Mann, in his book Creating a Lean Culture includes accountability as an essential element of a “Lean Management System”.

An accountability process enables a team to efficiently fix and prevent problems. This includes quickly identifying, communicating, assigning, tracking and closing the scores of problems an organization may encounter every day. If their accountability process is clumsy, not followed, or non-existent, a team can soon drown in its own problems. That is what a culture of firefighting looks like.

Mark Edmondson

Great article and great comments. I’m afraid that in large, highly hierarchical, organizations accountability finger pointing will remain directed from the top down. The hierarchy itself is a big part of the process that creates this effect. This article caused me to look up accountability and led me to this great quote by Viktor Frankl from his book Man’s Search for Meaning:

“Freedom, however, is not the last word. Freedom is only part of the story and half of the truth. Freedom is but the negative aspect of the whole phenomenon whose positive aspect is responsibleness. In fact, freedom is in danger of degenerating into mere arbitrariness unless it is lived in terms of responsibleness. That is why I recommend that the Statue of Liberty on the East Coast be supplemented by a Statue of Responsibility on the West Coast.”

I think that sums it all up well!