Mark's Note: I'm away on vacation through November 6… there will be some guest posts in this spot during that time. Today's post is by Richard Campos, who I met when he took my “Healthcare Kaizen” class in Denver back in April and we've kept in touch since then.

By Richard Campos

“Let us go down and there confound their language, that they may not understand each other's speech”

Genesis 11:7

Think back to the time when you first worked in quality improvement. You remember the amazing leaders who really taught you how to solve problems. You learned fast, had your successes, and got ready for the big world of process dysfunction. Then, one day, a shocking discovery: what you learned wasn't the only way to succeed. You decided to learn the other ways. You might as well have signed up for a language class.

Language has been around for a very long time. In his fascinating TED talk, evolutionary biologist Mark Pagel describes language channeled through speech as a “neuroaudial technology for rewiring other people's minds, without either of you having to perform surgery.” Language is our vital way to quickly spread ideas and accumulate social learning.

This “most potent trait” turned out to be too much for its own good. In the Tower of Babel story, people are scattered by language and spend their days, well, babbling. If you think it's challenging just to get ideas across in one language, can you imagine two? The set-up cost of going between languages feels like a neural switch between worldviews. So, it's humbling to realize that the world today has upwards of seven thousand languages.

People have also solved problems for a very long time. The road is well travelled: diagnose, treat, repeat. We observe symptoms and determine causes. We apply remedies to the causes. We study the results and try again, if symptoms persist. In our 20th Century version of the Babel story, we inherited Lean, Six Sigma, Shainin, Theory of Constraints, Global Eight Discipline, and more problem solving approaches. We think there are less than seven thousand of them out there. Let's take three examples: Lean, Six Sigma, and Shainin.

Just as language has symbols, syntax, and cultural context, a problem-solving approach has tools, roadmaps, and management ethos. Let's see how the analogy, with some allowance, helps highlight some key points.

1) Languages change.

Languages evolve to fit the places and the times. In a fascinating project, the Globe Theater of London performed Shakespeare in original pronunciation to reveal surprising results (video). Looking further back to Old English gives an idea of just how much the language has changed.

Lean, Six Sigma and Shainin have also changed over time. In Lean, autonomation techniques predated those for production leveling. The original Six Sigma roadmap did not include a “Define” phase. In the Shainin System, multi-vari analysis predated the Red-X method.

Besides tool additions or roadmap modifications, there are also terminology adaptations. This is particularly so for Lean, where instruction can get obscured by romanized Japanese terminology (isn't ‘waste' instead of ‘muda' sufficient for English audiences? For a range of opinions see this article from LEI). Taken all together, these changes bring flexibility as structured problem solving moves from the manufacturing floor to the office floor, the operating room, the design room, and beyond.

2) Languages are distinct.

Although some language mixing is inevitable, no one has adopted Spanglish or Franglais as an official language of the United Nations. “Lean Sigma” falls into this trap, occasionally pulling me along. What Lean Sigma speakers are really speaking is Six Sigma with embedded Lean tools, but it's not Lean any more than Spanglish is Spanish.

The missing component in Lean Sigma is the management ethos of Lean, which promotes an accessible and pervasive culture of continuous improvement principled on respect for people. For Lean speakers, the reverse situation is also true, as the embedding of DMAIC tools into A3 reports does not make it Six Sigma, just Lean with embedded Six Sigma tools. This may in turn miss a pervasive culture of structured validation and verification principled on financial and statistical thinking.

3) Languages are mistranslated.

The inevitability of translation error is immortalized by the Italian wisdom “traduttore, traditore!” (translator, traitor!). Some translations are funny, and some are fatal: “our wines leave you nothing to hope for” (This, and many other beauties, are collected in this article).

Translation errors also occur in the problem-solving world. Examples include the translation of ‘Kaizen' as meaning only “Kaizen Events” that are done as part of Six Sigma belt projects; or the translation of the DMAIC ‘Measurement Phase' as just a gathering of process data for quality circles. When we translate our problem-solving concepts, we owe it to ourselves and our audiences to verify the closest meaning of terms.

4) Languages interrelate.

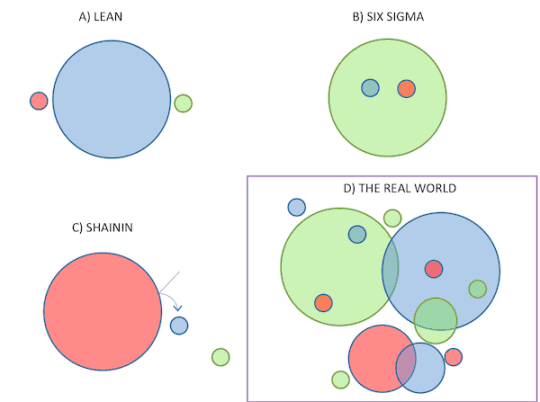

Quebec's Bill 101 is an instructive relational model of language coexistence bursting with cultural passion (see here). Cultural passions can also burst between problem-solving practitioners with ‘language' preferences. In practice, our workplaces are already more like Quebec than London or Paris. Interrelational models from the perspectives of Lean, Six Sigma and Shainin, are illustrated in Figure 1, where Lean is represented in blue, Six Sigma is in green, and Shainin is in red.

Figure 1(A) shows Lean as “Jupiter” the gas giant with Six Sigma and Shainin as nearest moons. Gravity pulls Six Sigma and Shainin tools in when they are needed.

Figure 1(B) shows Six Sigma as “Pacman”. It gobbles both Lean and Shainin tools and burps Lean Sigma.

Figure 1(C) shows Shainin as “Superman”. It's impenetrable to Lean and Six Sigma tools on its Red-X trajectory.

Finally, Figure 1(D) shows the real, interesting, convoluted and beautiful world of problem solving. This reminds me of coexisting perspectives, as one might find in cubist art. When we are open to different models for problem solving, we arrive at physicist Niels Bohr's wisdom: “the opposite of a profound truth may well be another profound truth.”

5) Language conveys meaning.

It's worth keeping the end goal in mind. The purpose of problem solving is to solve problems. As LEI's John Shook points out, we solve “little ones, big ones, wicked ones, sticky ones, concrete ones, fuzzy ones.” When we apply Lean, Six Sigma, Shainin or something else, it pays to remember the Babel story. No one approach will solve all problems, all the time. Each company has to figure out the relational model that works best for its business. Isn't that what our customers expect us to do?

What are you doing today to grow your team's problem-solving agility?

Richard Campos is a Business Improvement lead for a medical device company based in New Jersey, focusing on Lean and Six Sigma implementation in transactional and operational work environments. Richard started his journey in 2006 as a Six Sigma black belt and has grown in roles within various industries as he actively promotes a daily improvement culture. Richard doctored in Applied Physics from Columbia University and welcomes discussion about how science and art impact our lives. Richard invites you to connect with him via Twitter (@RCamposMBB)

What do you think? Please scroll down (or click) to post a comment. Or please share the post with your thoughts on LinkedIn – and follow me or connect with me there.

Did you like this post? Make sure you don't miss a post or podcast — Subscribe to get notified about posts via email daily or weekly.

Check out my latest book, The Mistakes That Make Us: Cultivating a Culture of Learning and Innovation:

Richard;

Perfect point about each company finding what fits best. The organizational culture and current state must be realized before beginning to develop problem solving. We have certainly been in the middle of this change for the past couple of years. With a specific focus on influencing a deeper level of cross-functional collaboration between functions, we’re working on being efficient with 5-why’s. We’re making ground but found out early on that we needed to simply and work developing a culture of reflection first before digging into using the other tools. Really enjoyed the post.

Rick, thank you very much for the comment, glad you enjoyed the post. I appreciated the insight you gave into your setting and the importance of reflection in your organizational journey. Deming was up to something good when he put the study between the doing and the acting…

Hi Richard

You make some great points about language and attitude issues, I feel I am far more a promoter of Continuous Improvement, as opposed to promoting any one branch of it. In fact I feel that under the proper culture and organization can apply many different tools, using those that best apply to the current problem at hand. There really shouldn’t be a competition between the tools, after all does a hammer and a wrench compete, no they both have their jobs to do, and sometimes they actually even work together, so should we people.

Hi Robert, thank you for the comment, great that you are promoting tool use flexibility. I find that lookbacks are also very useful to learning agility… ‘was THAT the best way to the effective countermeasure?’. Mark Graban has a great post on analysis paralysis (Sept 10 2013 – “Don’t let looking at data blind you…”) which is a good case study. The comments are very good reads as well. Even the improvement professionals have their improvement cycles..