My wife is a leader in a business (not GE) that does aircraft engine “MRO” work – maintenance, repair, and overhaul. I've been able to visit her shop floor (her “gemba”) and we noticed similar parallels between their work (bring engines back to prime “health”) and what's done in healthcare. This parallel was also explored in this recent article from GE Healthcare that was published by The Guardian in England: “What lessons can healthcare learn from industry?”

My wife is a leader in a business (not GE) that does aircraft engine “MRO” work – maintenance, repair, and overhaul. I've been able to visit her shop floor (her “gemba”) and we noticed similar parallels between their work (bring engines back to prime “health”) and what's done in healthcare. This parallel was also explored in this recent article from GE Healthcare that was published by The Guardian in England: “What lessons can healthcare learn from industry?”

There are interesting and sometimes humorous parallels between engine MRO and human healthcare:

- Engines need regular preventive maintenance, inspection, and repair during their life cycles (something people should get, as well)

- Appointments are scheduled for the engines with a list of ways in which the engine is “ailing,” but there is a lot of variation in the work because “every engine is unique,” as they might have the same design and the same parts, but each one wears a little differently (just like people).

- Each engine gets assessed to discover what other work should be done – the engine is “admitted,” some parts are x-rayed, and sometimes a tiny camera is inserted deep inside the engine via a long, flexible tube (ouch!).

- Quality should be the first priority, as it can be a life-or-death issue if the work is not done properly.

The main difference, of course, is that the engine (as the “patient” in an MRO shop) doesn't have feelings to be aware of and to address, but emotions can run high if the customer doesn't get their engine discharged to them on time.

GE Healthcare, in their article, writes about how NHS organizations in England have learned about Lean and Six Sigma by visiting a GE engine MRO site (and a GE Healthcare site) in Cardiff, Wales.

I would agree that there's a lot to learn from a well-managed industrial site and I'd add that there's much for industry to learn from visiting a well-managed hospital (for example, some manufacturers have gone to visit and learn from my friends at ThedaCare).

One key cultural lesson that is valuable and transferrable, as expressed by GE:

“We reward our employees for flagging any quality issues, even if they have been at fault themselves. If there's a quality issue, whatever the reason, we want to know about it, and we'll applaud that. A blame culture is the last thing we want when we're dealing with something as critical as aircraft engines.”

Many organizations in the “Lean Healthcare” community, along with those in the modern patient safety movement, emphasize the need to move from a “name, blame, and shame” culture in healthcare. When people are under pressure to cover up problems, patients suffer. We can't fix the system and prevent future problems if current (and potential) problems are not discussed openly.

Another quote from a GE leader:

“Kevin Gauci, production manager at the Life Sciences facility said “With this sort of size and scale, the right sort of leadership is imperative. A collaborative leader operating with humility and respect is key. I like to think of it as a reverse pyramid – the guys on the shop floor are the priority – they're the heartbeat. Everyone else needs to help those operators who are touching the products to do their jobs and get these products through the system. I guess there are parallels there with the nurses, doctors and surgeons on the front line with the patients every day.”

ThedaCare, for example, uses the servant leader reverse pyramid model, as I saw again last week. Their CEO, Dr. Dean Gruner, is listed at the bottom of the organization chart since he supports people doing the work, instead of being a top-down “command and control” leader.

An NHS leader (from a hospital I was able to visit with LEI and Dan Jones in 2009) said:

Deborah Burrows, head of transformation at Portsmouth hospital explained “We have tried to implement Lean at Portsmouth, so this visit gave us the opportunity to see Lean operating in a different environment and to look at the processes, without getting sidetracked by all the healthcare going on around us! I've been very impressed by the standard metrics GE uses, so everyone reports in the same way and it's all understandable and transferrable between departments.”

I cringe a bit at the phrase “implementing Lean” because it sounds like we're installing a new countertop in a kitchen instead of working on an ongoing culture change and transformation. “Implement” isn't a good word, because it seems to imply being “done” at some point, instead of continuing to manage in a new way and always improving.

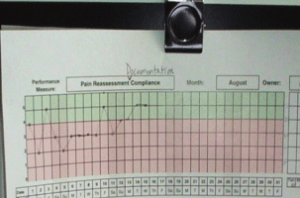

The other thing I'm not crazy about is the whole “red/green” business, as a visitor commented on:

“how GE manages operational performance day to day, saw the scorecards and dashboards used to keep metrics ‘in the green'

Unfortunately, I see a lot of this in Lean healthcare, even some very well known hospitals. Once you understand Statistical Process Control and common cause variation, the overly simplistic comparison against a goal (red = worse than goal and green = better than goal) just doesn't hack it anymore. If average performance is right at or near the goal, having to “find a root cause” for every red data point is generally a waste of time since the red data points are often just caused by normal variation or noise in the system. Improving this sort of system requires fixes to the everyday system, not reactions to specific data points.

Unfortunately, I see a lot of this in Lean healthcare, even some very well known hospitals. Once you understand Statistical Process Control and common cause variation, the overly simplistic comparison against a goal (red = worse than goal and green = better than goal) just doesn't hack it anymore. If average performance is right at or near the goal, having to “find a root cause” for every red data point is generally a waste of time since the red data points are often just caused by normal variation or noise in the system. Improving this sort of system requires fixes to the everyday system, not reactions to specific data points.

The goal is not “keeping metrics in the green” (as this can be done by cheating or fudging the numbers) – the goal is meeting customer needs and working continuously toward a state of perfection.

I'm going to write about this again in a future post.

Please scroll down (or click) to post a comment. Connect with me on LinkedIn.

Let’s build a culture of continuous improvement and psychological safety—together. If you're a leader aiming for lasting change (not just more projects), I help organizations:

- Engage people at all levels in sustainable improvement

- Shift from fear of mistakes to learning from them

- Apply Lean thinking in practical, people-centered ways

Interested in coaching or a keynote talk? Let’s talk.

Join me for a Lean Healthcare Accelerator Trip to Japan! Learn More

Having worked in the MRO industry I can say that there are many similarities not the least of which is dealing with ambiguity on a daily basis. On the other hand there was a deep respect for process and standards in the MRO industry that healthcare institutions could learn from. Early in my career we got notice of a passenger airplane that had lost an landing gear at take-off. We tracked its progress on CNN as it plan flew to its home base. Before the plane landed we had pulled the repair documents (charts) to see if we had missed a key operation. Fortunately the plane landed without harm of life. It turns out that a field maintenance process had not been followed.

One big difference is that MRO organizations can set components aside to deliberate the best approach for special cases without causing further damage. Healthcare institutions generally can’t afford to do that with patients.

Thanks for pointing out one of the differences, Bart.

Hi Mark

You make several very good points, first there are often parallels and ideas we can draw from other types of businesses, and by doing so we may be able to come up with new ideas to solve our problems.

The next is that for a culture to truly support continuous improvement, they have to stop finger pointing and blaming each other. By shifting the emphasis from blame to cooperative problem solving you empower and drive change and improvement, because you have eliminated fear.

Another is that leaders need to consider that they exist to support the rest of the organization and not the other way around.

Lastly is that any metric can be used for good or in reality become a problem in and of itself. I have seen SPC used early in a process improvement effort do great things, then latter on it became the single biggest problem they faced, because it was wasting their time chasing after ghosts. Common sense needs to be applied so that metrics keep working for us and not against us. But blindly chasing any set of numbers is just plan dumb, and can in fact lead to you doing many things that are counterproductive.

Thanks, Robert.

I’d argue that SPC, done well, is exactly the method that’s supposed to prevent people from “chasing their ghosts” and overreacting to every common-cause variation data point in a chart.

Robert,

Can you explain how SPC caused people to be “wasting their time chasing after ghosts”? I’m really interested in the answer since, as Mark says, SPC should do the opposite. I’m always keen to find the limits of any method.

Rob

Dear,

I find the quote from GE very interesting: “We reward our employees for flagging any quality issues, even if they have been at fault themselves. If there’s a quality issue, whatever the reason, we want to know about it, and we’ll applaud that.”

Can anyone share how she/he reward people for flagging a qualityt issue?

regards

Geert

I’d like to think that the times when “they have been at fault themselves” would be a relatively small percentage of the time (most problems being caused by the system).

I wouldn’t give people a cash bonus as a “reward” for flagging problems. I’d think of it more in terms of 1) not punishing them and 2) giving them recognition in a way that encourages more of that behavior (again, probably NOT cash or money rewards).

While it is not a “reward” per se, our organizational leaders are trying to practice giving 5:1 feedback in order to build a highly reliable culture of safety in our hospital. We want to recognize positives five times for every one time corrective feedback is given over time (not all in one conversation).

Positive “catches” are reporting things such as safety near-misses, practing safe behavior, or alerting about defects passed on in a blame free. Saying thank you and treating problems as treasures and gems that lead to improvement.

The red/green thing has some pluses and minuses for us. We use it on the team’s Continuous Improvement Action Sheets, which capture the ongoing improvements. A meaningful due date is given, with an owner for accountability, of which many of the team members throughout the organization are inputting the action for themselves. If it is late the cell turns red and on time it turns green. In our situation, the goal is to provide an overall snapshot if we’re being consistent in finishing the tasks in a timely manner. Yet, we have some that still believe that green is the goal and not improving customer value by completing the action. Once a month, I report out on our on-time/late tasks as a basic, “what is the current state,” and those not watching or following up on their actions all of a sudden go into paranoid mode. Our culture is a work in progress. The green/red is to keep a little “tension” but not “stress” as our friend, Jamie Flinchbaugh shares in the “Hitchhiker Guide to Lean.”

We continue to find that a positive attitude that focuses on the process, while authentically showing gratitude to the team members, who bring up issues, has a great effect upon a no-blame culture.

Hi Rick-

I’m not against all things red/green.

What you’re describing is different than what I was talking about. I was talking about red/green zones in charts.

My concern with any red/green is that we have to be careful that the culture is one where, when somebody is “red” on something, that leaders react with a “how can I help?” attitude instead of a “you’re being held accountable, ahem, in trouble.” Like you said, it has to be a no-blame culture, or people pad due dates, etc. to make sure nothing is ever red (some Alan Mulally dealt with at Ford when he arrived: LINK.

Mark

Comments are closed.