Growing grapes and making wine is certainly an art… but when you look into it there's a lot of process involved. As I wrote about a bit last week, my wife and I recently spent two days in Sonoma County and two days in Napa County, California. She would cringe if I called these “gemba walks,” but you learn quite a bit about not just the wines, but also how they are made.

And, as I'm pretty bad at vacationing, I saw many things through a Lean lens that I thought were interesting… maybe there's something here that's helpful or thought provoking to you. Or, maybe you like wine, as well. Click on any of the photos for a larger view.

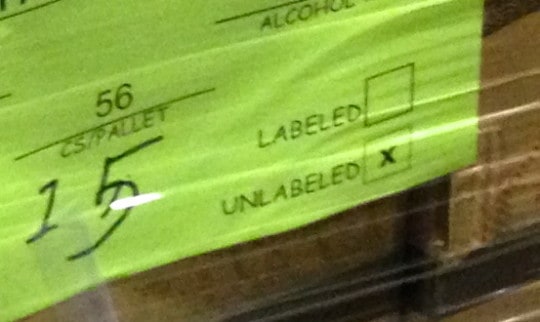

Delay and Rework on Labeling Bottles

One winery (name withheld and obscured in the photos) was taking us through their warehouse and pointed at some cases of wine that had just been bottled a few days earlier. The problem wasn't so much the inventory (they weren't holding it that long), but rather the amount of rework that was going to be involved.

Somebody in our tour group asked why the green sheet had an “X” next to “UNLABELED.”

The guide said, ‘Oh, those bottles don't have labels on them.”

Well sure, that seemed pretty obvious. My wife asked “why?” (see, she's a Lean thinker too). The wine clearly needs a label to be sold legally (and for it to look right to customers).

The guide explained that the labels hadn't arrived from the printer in time for the day when the winemaker decided it was time for the wine to come out of the aging barrels into the bottles.

If you're asking, “Why couldn't they do it right the first time?” as in waiting for the labels (and the guide indicated that this was a problem, not the norm). Ideally, they would bottle and label at the same time.

Well, the wine sitting in barrels is not inventory… it's undergoing a “value adding” process as the wine is being changed by the aging in the oak. If the wine bottling waited for the bottles to arrive, it might (in the winemaker's opinion and judgment) “overage.”

Well, the wine sitting in barrels is not inventory… it's undergoing a “value adding” process as the wine is being changed by the aging in the oak. If the wine bottling waited for the bottles to arrive, it might (in the winemaker's opinion and judgment) “overage.”

So, you have wine in bottles, inside of case boxes, on a pallet, wrapped in plastic. Once the labels arrive, they will now tear this all apart and put the bottles through the labeling line. There's certainly some extra work and some “waste” involved. You can see from the two check options that “UNLABELED” bottles must occur often it enough for it to be considered a standard option.

It happens enough that there's an industry term for this — “shiners.”

It seems like there might be a risk of unlabeled bottles mistakenly getting shipped onto a truck. It might be better error proofing if unlabeled bottles/cases had a bright red sheet instead of just relying on a check in a box and somebody potentially misreading it. There are important regulatory reasons to be concerned about this.

It seems that the wineries would want to err on the side of ordering the labels way early. It's better, probably to hold an inventory of labels than it would to have to perform this re-work on boxed bottles.

You might wonder, “Well, maybe they need to wait to see what the alcohol content percentage is going to be before getting the labels printed”? I think the winemaker can check the alcohol percentage some relatively short time before bottling and it's not going to change significantly. If the label printing lead time is three weeks, maybe you'd check the alcohol percentage in the barrel and then give the final number to the label printer? It would be good to have a “Lean label printer” near by with short lead times and predictable delivery.

(Note – some of this is guessing and speculation… if I owned a winery and were doing a real “gemba walk,” I'd ask enough questions to get real facts, but we were on a public tour and could only ask so many questions.

Preventing Grape Overproduction

During the grape growing process, the winemaker and vineyard managers at a number of wineries talked about being careful to make sure the vines aren't growing TOO MANY grapes. You might ask “what's wrong with producing more?”

There's a tradeoff between the volume of grapes and the taste or quality. Having fewer grapes on the vines means that flavors are concentrated and you get a better end result. They routinely prune the grapes, which then drop to the soil and become part of the fertilization and soil content. See the bottom of this picture:

Is the Customer Always Right? How Much Variation Can You Have?

There's a balance to be found between producing wines that customers want to buy (at the price you are hoping for) versus the winemaker's vision (and the owner's vision).

Some wineries work very hard to produce a very consistent wine each year (through careful blending). Some winemakers go with the annual variation in the soil, weather, and other conditions and produce wines that are different each year (within the same general style range).

A couple of winemakers said basically, “It's easy to make good wine in a good year… but the real skillful wineries can produce a great wine in a challenging year.”

OK, this post is getting long… more to come later this week.

Also see a post of mine from last year about visiting the Champagne region of France.

Cheers!

What do you think? Please scroll down (or click) to post a comment. Or please share the post with your thoughts on LinkedIn – and follow me or connect with me there.

Did you like this post? Make sure you don't miss a post or podcast — Subscribe to get notified about posts via email daily or weekly.

Check out my latest book, The Mistakes That Make Us: Cultivating a Culture of Learning and Innovation:

[…] Gemba Wine: A Lean Geek Visits Wineries, Part 2 […]