A woman has the wrong side of her brain operated on. The headline features the hospital's name and the surgeon's name. It seems the “name, blame, and shame” process has begun.

SSM Health Care St. Louis, Dr. Armond Levy face lawsuit after wrong-side brain surgery

In complex systems, like healthcare, is it overly simplistic to blame the surgeon? Probably. One could say the hospital system owns responsibility for the overall process and outcomes… but surgeons are often not employed by the health system, which complicates things.

Are we focused on learning and improvement, or blame and punishment?

From media accounts, what happened to the patient, Regina Turner?

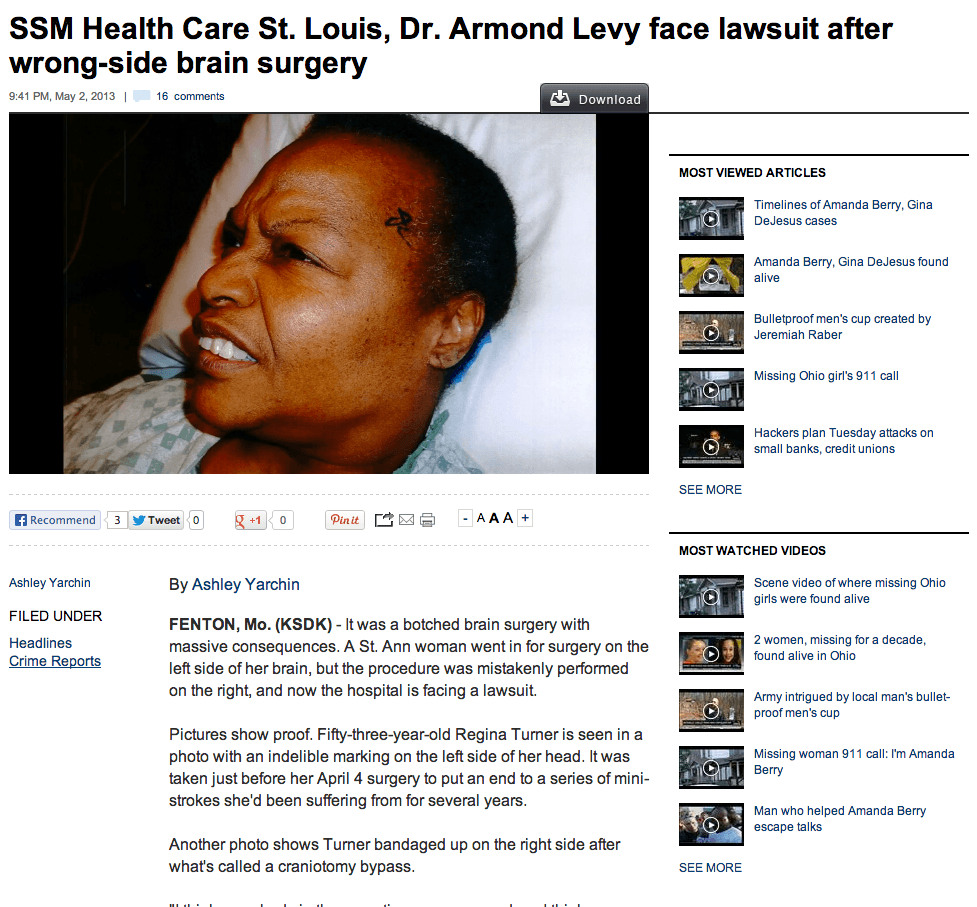

A St. Ann woman went in for surgery on the left side of her brain, but the procedure was mistakenly performed on the right, and now the hospital is facing a lawsuit.

This definitely falls in the category of a so-called “never event” – a wrong-side/wrong-site surgery. They are called never events because they SHOULD never happen… but they do happen, sadly. If we had good processes and systems, errors like this would never happen.

So, when they do happen, do we shake our heads and say, “ah, human error… we're human, so we can't expect perfection… errors will happen.” Or, do we punish that “bad apple” so that individual can't make the same error again? Would we strip the surgeon of their license? Throw them in jail? Either of those actions would probably result in a huge loss to society, removing a skilled surgeon who was involved in one mistake.

Writing “involved in” might sound like passive voice abuse… but the surgeon does not work alone. It seems overly simplistic to automatically attribute an error to a single person working in a team.

From this case, the news reports say:

- There was a surgical site marking (a good practice)

- The marking was done on the WRONG SIDE (so we'd then ask why this occurred… and how could we error proof the system to ensure this doesn't happen again).

I thought the best practice was for the surgeon to personally mark the site. The surgeon should be familiar with the patient and the case, as to know whether they are supposed to operate on the left or right side of Regina Turner's head. It's easy to see where errors are more likely to occur if the surgeon is not involved, if the marking is done by a nurse.

I've thought it seems smart to also mark “NO” or “WRONG SIDE” in addition to marking the surgical site. Markings sometimes get wiped away or washed off during surgical prep (which gives us another “why?” to ask and another countermeasure to find).

Turner's attorney said:

According to the Journal of Neurosurgery, Wolff pointed out, there have been 35 documented cases of wrong-side craniotomies ever in the U.S.

If the hospital and surgeon have a standard process that says the surgeon IS supposed to mark the site, and they did not, we'd want to ask “why?” The surgeon might have been under time pressure. But, surgeons and physicians have a lot of power and relatively high levels of autonomy, so I'm less forgiving of a surgeon who feels pressured into rushing or cutting corners. I'm more forgiving of a nurse or somebody lower in the traditional hierarchy.

In the Turner case:

“Sometimes the x-rays can be flipped,” he explained. “Sometimes the doctor doesn't look at the medical records. Sometimes the surgery comes off late and everybody's in a rush. Sometimes, if a doctor has a whole lot of surgeries, let's say he's got eight knees to do that day, and he's got four right knees and four left knees, and the first knee cancels and they start moving everybody up, the wrong knee goes in the wrong room.”

Some of the errors:

- X-ray was flipped — why? Can this be prevented through process or technology?

- Sometimes MD doesn't look at the medical records — why?

What's the right balance in “holding the MD accountable” and recognizing they work in a system?

- Sometimes things run behind schedule and “everybody's in a rush” — why are things behind schedule? why is everybody in a rush?

- If a patient cancels, is there a good process to ensure that everything else stays in sync to prevent wrong-patient mixups??

Whose responsibility is it to make sure people don't rush? I had outpatient surgery a few years ago and things were running at least three hours behind schedule. The surgeon apologized, but I agreed that it's better to do quality work on all the other patients, as I didn't want the surgeon rushing through my case either.

If the “rush” is driven by the behavior of an individual surgeon, we might hold them more personally accountable.

But, what if the “rush” was driven by something more complicated? Maybe the department had targets or incentives (or punishments) that resulted from on-time case starts or some other metric? What if the scheduling template wasn't realistic and cases weren't scheduled with enough time? What if the surgeon had been yelled at previously for taking too long in the O.R.? Does management ever get held accountable for their behavior that might cause people to rush and cut corners?

This could be far more complex than “bad surgeon.”

The patient's attorney said:

“I hope everybody who is operating on people pays a lot more attention because more healthcare providers are really, really good,” Wolff added.

I agree that healthcare providers are generally outstanding people – smart, caring, motivated, and hard working. I disagree that asking people to “pay a lot more attention” is a good root cause countermeasure. We need to design better systems, not just say “be more careful” with warning signs and slogans.

As I blogged about yesterday, the patient is a victim here, but the surgeon and the entire surgical team might be “second victims,” as well.

The system issued this statement:

“St. Louis SSM Health Care and SSM St. Clare Health Center sincerely apologize for the wrong-site surgery in our operating room. This was a breakdown in our procedures, and it absolutely should not have happened. We apologized to the patient and continue to work with the patient and family to resolve this issue with fairness and compassion.

“We immediately began an investigation. We have since taken steps to be even more vigilant to prevent such an error from happening again.

“Medicine is a human endeavor, and sadly, people and systems are not perfect. When an error occurs, it is tragic for the patient, their loved ones and the medical team.

“Our SSM St. Clare Health Center team is made up of dedicated health care professionals who are devastated. We can and will do better. That is our commitment to the community.”

I hope the system understands why there was a “breakdown in procedures” so it can be prevented in the future. I hope those steps include process improvement and not just greater “vigilance.” Dedicated, vigilant professionals are a good start – but not wholly sufficient.

We can and must do better. What has your hospital done to ensure that wrong-side / wrong-site / wrong-patient surgeries cannot occur? How does your words about commitment to your community manifest in process improvement actions?

Please scroll down (or click) to post a comment. Connect with me on LinkedIn.

Let’s build a culture of continuous improvement and psychological safety—together. If you're a leader aiming for lasting change (not just more projects), I help organizations:

- Engage people at all levels in sustainable improvement

- Shift from fear of mistakes to learning from them

- Apply Lean thinking in practical, people-centered ways

Interested in coaching or a keynote talk? Let’s talk.

Join me for a Lean Healthcare Accelerator Trip to Japan! Learn More

Hi Mark

It kind of strikes me that often in healthcare there is a lack of redundancy. In most manufacturing we have some way of backing up most critical checks. Take the food industry each sensor requires two back up sensors, each human reading requires at least one other person to take the same reading with a different device.

The same holds in the commercial aircraft pilots and mechanics each have backups that recheck their work and have to sign off (co-polit and another mechanic).

Yet in most health care matters people rarely even seek a second opinion in reality, and there is no automatic back up system to ensure the results are correct. Duplicated checks do add cost, but they prevent a great many problems.

Mark: My wife Judy died a preventable death Sat 29-Sep-2012 following what a medical colleague refers to as a ‘catalog of errors’. The errors in that catalog ranged literally from a) to z), as follows:

a) The 1st error was when the surgeon even attempted laparoscopic gall bladder removal surgery knowing from previous x-ray and MRI images that the: “…neck of the gall bladder was ill-defined…” (we now know from medical experts that such information should have indicated general surgery under controlled conditions);

b) The surgeon punctured Judy’s duodenum at approx 9:00 AM Thu 27-Sep during what should have been ‘routine’ laparoscopic gall bladder removal surgery. Unfortunately, that was compounded by:

c) Bile leakage from an approx 5 mm dia hole that wasn’t observed during a pre-close video inspection and started flooding Judy’s body cavity with toxic fluids;

d) While in the recovery area, even though Judy was experiencing excruciating pain requiring multiple Dilaudid doses, she was cleared for discharge from a day surgery campus Thu 27-Sep at 1:45 PM after a 1 hr 45 min delay to administer additional pain killers (ie: just under 6 hours following surgery);

e) Judy was discharged from that day surgery campus without having ingested fluids or voiding (contrary to the campus’ published guidelines);

f) The discharge nurse’s response to our questions about the pain Judy was experiencing was to describe it as: “..normal..”;

g) The discharge resident’s solution to Judy’s excruciating abdominal and chest pain – that doubled a woman with a ‘high’ threshold for pain over in agony – was to provide a prescription for Dilaudid;

h) We then had to find a pharmacy to fill that prescription – not an easy task for such a drug – that gave no relief whatsoever when administered to Judy at 4:00 PM;

i) As soon as the Dilaudid had been administered at home, we checked the Laparoscopic Surgery Patient’s Guide provided by the Campus where we found that the only reference to chest pain/abdominal pain suggested that some patients might experience this and that it might indicate heart issues [subsequent research finds that most other hospital’s Guides make reference to the risk of sepsis];

j) When, at 7:00 PM, 911 was called because Judy was literally ‘climbing-the-walls’ in agony and, when checked by the first responder, her pulse was 50% higher than normal and she was breathing in short gasps (what we now know to be tachypnea) [BTW: both of these vitals we now know to be acknowledged precursors to septic shock];

k) Even though Judy was deemed to be not at risk for heart attack, the paramedics who had arrived shortly after the first responder were sufficiently concerned about her condition that they transported her to Emergency;

l) At 8:00 PM when she arrived at a full-service campus Emergency dept, she was registered but not triaged immediately, even though I had taken Judy’s file with me and shown the registration desk nurse the day surgery campus Discharge documents from 6 hours before;

m) Against my quiet protestations, Judy was then left in the Emergency dept corridor for 2 hrs 45 mins under the watchful eye of the paramedics [who, in accordance with Campus policy, couldn’t be released until Judy was admitted];

n) Every 30 minutes or so, if I saw medical staff, I asked when Judy would be attended to but got no satisfactory reply and felt obliged to not get too agitated [the ever-present signage describing the Campus’ “zero tolerance to abuse policy” convinced me that I would be of no use to Judy if I were thrown out];

o) At 11:45 PM when Judy was finally admitted to Emergent, I then repeated the process of presenting the day surgery campus Discharge documents from 10 hours before;

p) After sitting with Judy for almost 2 hours with no apparent intent on the part of medical staff to attend to Judy [and having asked nursing staff every 30 minutes or so when Judy would get attention], Judy let me know that she was in significant discomfort due to not having voided, at which I point I helped her to the bathroom;

q) When, at 1:30 AM Fri 28-Sep, Judy returned and explained to the nurse that she had been physically unable to void, the nurse inserted a catheter;

r) Immediately prior to this, Judy had attempted to drink fluid, but was unable to swallow any, at which point the nurse set up a fluids intravenous drip [we now know that the inability to drink fluid and void is an indication of septic shock];

s) A further 2 hours passed by with still no attention other than a cursory visit and examination by a junior resident at which point I said to the nurse that, if they continued to not administer pain killers, I would go home to get the Dilaudid prescription collected earlier and administer them myself [which I followed through on at 3:30 AM];

t) In my absence, at approx 4:00 AM, Judy was taken for x-rays & then ‘admitted’ to a hospital ward between 5:00 and 6:00 AM Fri 28-Sep;

u) I had asked my step-daughter to take my place with Judy and shortly after she arrived, the surgeon who performed the laparoscopic surgery at the day surgery campus the day before stopped by the room and, without acknowledging or making eye contact with my step-daughter, told Judy that: “…it’s entirely possible that your duodenum was ‘nicked’ during the surgery due to the neck of your gall bladder being ‘ill-defined’ and stomach fluid is trickling into your body, so we’ll take an MRI to determine the extent and then you’ll need to be operated on in general surgery some time this morning to repair the damage…”, this being said to a woman who by this point was almost unresponsive;

v) After receiving a text from my step-daughter describing this exchange to me, when I arrived at the hospital just after 7:00 AM Fri 29-Sep, I asked the attending nurse when Judy would have an antibiotics drip inserted, to which the nurse responded that: “..the meds haven’t arrived from the pharmacy yet..” and this process was repeated on at least 15 minute intervals for the next 90 minutes with the same response;

w) From the time that Judy was put in the ward bed to the time when she first became unresponsive, there was absolutely no vitals monitoring attached to Judy;

x) At 8:30 AM, the duty surgeon for that day stopped by and when I learned that his specialty was as a pancreo-hepatic surgeon, I was overjoyed because I saw this as Judy’s saving grace, but my joy was short-lived because he explained that Judy was #3 in the operating room schedule and also explained that, although an MRI had been ordered, he wouldn’t wait for it because he was pretty certain what he would find [I could tell from the surgeon’s body language and expression that he was very agitated that Judy had been left unattended so long];

y) At 9:15 AM as I was sitting holding Judy’s hand, talking with her and telling her that her Dad sent his love and best wishes, as I squeezed her hand, it was completely limp and I realized that Judy was unresponsive, at which point, because there was absolutely no vitals monitoring attached to Judy, I went running down the corridor yelling for nurses to rush to Judy’s assistance; and,

z) After some nurses from a nearby ward worked on Judy, at approx 9:25 AM Fri 28-Sep, an ICU resuscitation team arrived – just as Judy ‘crashed’ for the first time – and resuscitated Judy, kept her as close to stable until a surgical team arrived, and then took her to the operating room sometime just before 10:00 AM.

The Outcomes:

The pancreo-hepatic duty surgeon told us 90 minutes later that he had opened Judy, lavaged her body cavity, but determined that there was such serious intestinal and organ damage that her chances of survival were minimal. Between 11:30 AM Fri 28-Sep and 11:30 AM Sat 29-Sep we now know that Judy was essentially on life support – it had been necessary for the surgeon to ‘pack’ Judy’s surgery site because he had been unable to close her up following the general surgery, this was because the damage was so severe and because Judy had ‘crashed’ a second time on the operating table. For the remainder of her time, Judy was hooked up to 16 devices [intravenous drips, a breathing machine, a dialysis machine, etc]. To be clear, the resuscitation team from the ICU; the duty surgeon and his team; and, the subsequent ICU teams did everything humanly possible to retrieve the situation.

So, you see, the ‘catalog of errors’ spanned the entire alphabet and the outcome was that, at 11:30 AM Sat 29-Sep, our family had the unenviable task of agreeing to remove life support from my dear wife who only 48 hours before had been a vibrant contributor to our family, our church, her work in public health, and her countless friends. At 1:00 AMJudy died following the incremental removal of life support.

In reality, Judy’s life ended the second time she ‘crashed’ when in general surgery sometime around 11:00 AM Fri 28-Sep, that being just 26 hours following her initial laparoscopic surgery. We now know that what we had assumed was drowsiness induced by pain killers was more likely to have been somnolence – being the body’s natural reaction to being poisoned by acidic, corrosive stomach fluids gradually sucking the life out of Judy.

We are now aware of the damage that sepsis and septic shock cause, whether the patient survives or dies. We are now aware that a patient’s chances of survival reduce (empirically) at a rate of 13% per hour following spread of infection, indicating that – as a consequence of no attention to her – Judy’s body would have been fully compromised between 6:00 and 9:00 PM Thu 27-Sep. Ironically, this empirical data was developed from epidemiological studies by a research scientist colleague of Judy’s in her role as coordinator for the Infection Control Division of a National Public Health Agency and is regularly cited in scientific papers and medical journals. As a family, we have commenced becoming advocates of awareness and proponents of procedures to reduce preventable death, particularly related to sepsis.

Mel – I’m so sorry to hear about your tragedy. Among other things, it illustrates how delays and waiting times (in overly busy ERs, pharmacy, imaging) can cause such harm. Efficiency and quality go hand in hand.

My deepest condolences. I’m glad you are working to help prevent tragedy’s like Judy’s from happening to other families.

Mark

Mark, I want to thank you for shedding light on such an important topic. This is a conversation that everyone needs to have, and awareness needs to be drawn to such horrific mistakes.

Agreed. Such a tremendously important discussion that I hope generates real change in the system. Tragedies like this are indeed preventable. They need to be addressed.

As an afterword, the system is still failing us because the autopsy hasn’t been officially released and the Coroner’s Report can’t be published until it is – a full 34 weeks following Judy’s death.

Mel –

My sincere regrets and I hope you are able to get some closure by receiving the response you deserve.

Regards,

Chad

a catalog of errors right from ER to OR. This fiasco should have and could have been prevented

I was present when Judy left us every one on staff knew that this was a situation that should have been avoided

” to every thing there is a season, and a time to every purpose under the heaven”

we miss you daily Judy

Claude

Hi Mel,

I am so sorry for the suffering Judy went through as a result of this surgical error. I am so sorry for the suffering you and your family are enduring in the loss of Judy’s life. There are processes in place to find these things and clearly the process was not followed. Also, the level of pain Judy experienced, along with the fact that she should not have been discharged when the hospital staff were not assured that her system was back up and functioning properly. Too many errors here. I hope that justice is done so that this doesn’t happen again.

How can “the system” fail so badly and so repetitively in one person’s care?! Reading this full breakdown of what actually transpired is like a vicious kick to the mid-section. It is almost beyond my ability to make sense of.

There is definitely trouble “in the trenches” of healthcare. My wife spent many years as an RNA in numerous hospitals and has enough horror stories of mis-management, insensitivity and negligence to write a fair size novel.

Those who manage and mandate operations and policies need to wake up to the fact that things are broken and on the verge (in some cases) of total collapse.

Stories like Judy’s should ring like a huge klaxon throughout their offices; calling them to roll up their sleeves and dive into the current mess. It’s time to dig in, people. It’s time to fully admit where we’ve come to, recognize all of the shortcomings and start making the changes that will help restore our collective faith in health care. It’s simply too important not to.

Every life, is a precious life. Here’s hoping that those entrusted to care for us can fully embrace their role as active and passionate protectors of those lives.

Hi Mel,

I’m so sorry for your loss. I hope this tragedy brings awareness to to all hospitals’ staff and helps them improve their systems so this doesn’t happen again.

Regards,

Jaime

Not a day goes by that we don’t wish for Judy to be back with us, just for a few more minutes, to tell her one last time how much she is loved. I cannot think about this whole incident without thinking that it’s just one big nightmare. None of these mistakes should have happened, let alone all of them. We can’t stay silent any longer. As a society, we believe that doctors are higher beings, because they quite literally have our lives in their hands at times, but they still have to be held accountable for their actions. Every single person who failed Judy can say ‘sorry’, but that doesn’t undo what they did or didn’t do, and it doesn’t make the loss of Judy loss even the littlest bit easier. The fact that Mel still hasn’t received the Autopsy Report is absolutely reprehensible. That is just another failing of the system.

Judy, we love you and miss you.

Mel, you obviously have a dilemma – a coroner too busy to do his work in a timely manner.

On his routine, but long overdue, report hangs your next few steps. Deciding those steps depends on that report. Probably the coroner’s name needs media publicity and soon.

Should you and Judy’s friends make a case to the public in hopes of averting another death at the hands of the same doctor and a variety of medical errors at 2 Ottawa hospitals?

Clearly the first doctor must be properly re-assessed and not allowed to bury her “accident”.

Have the doctor’s colleagues submitted their own reports? Are they supporting a proper inquiry? Do you expect a copy of their documentation soon?

Clearly Ottawa Civic and Ottawa Riverside procedures were inadequate and clear contributors to Judy’s death. Will more unsuspecting people die before more malpractice preventions are in place?

You need an administrative team that will bombard hospital leaders and board members with the frustrations created by one coroner and the potential of their involvement in a ramped up media exposition of Judy’s treatment at the Riverside and Civic campuses.

Probably funding a legal team should become a focus as you enter the media world with your documentation.

You have many friends standing beside you! We are ready.

Mel,

While I realized that Judy’s passing had to do with a failure of our health care system, I had no idea that the mistakes made were so bad.

This is really disheartening.

I know that Judy is in a better place and at the same time, I support your efforts, Mel, and admire your courage in asking of the health care system questions that they otherwise will like swept under the rugs. Yet, these problems need to be addressed.

Canadians should not need to fear going to the hospital for a surgery that should have few attendants complications, and not the titanic type of problems that Judy experienced.

I still cannot fathom why a patient returns to the emergency unit of the same hospital where approximately 6 hours earlier had been discharged after an abdominal surgery, and will then have to wait for 10 hours to be re-admitted.

Something went very wrong.

For the hospital not to take a good and transparent look at such an elementary issue of quick re-admission after surgery, means something is still very wrong with this hospital, and there is a responsibility to put pressure on the powers that be to fix it.

I am very much with you on this, Mel.

Dele Ogunremi

Nice article. It is unforgivable if a surgeon marks the wrong side of the cranium and perform a surgery or perform an operation on a wrong eye quoting time pressure as a reason. These kind of negligence reflects primarily on the quality of the knowledge and their questionable smartness. A little bit of thinking and better communication goes a long way.

Shyam –

These systemic errors have nothing to do with the education level or “smartness” of the people involved. That’s exactly why we need better processes and systems – to prevent good people from making bad mistakes.

Mark

While I agree with the better process and systems, it still rely on the human performance and carefulness. How a surgeon would perform a surgery blindly without knowing the case history. That is certainly not smartness. Better process can certainly help but at the end, it is human error and not the process error.

Let’s say a surgeon does 1,000 surgical procedures and THEN has a wrong-site surgery. Did they suddenly get dumb? Are they suddenly unskilled?

A hospital and an operating room is a complex environment with many moving pieces. When things go wrong, it’s not because of one bad person.

Mark, I am not diagreeing with you. Having worked with some highly skilled ophthalmic surgeons, I know any responsible surgeon would first confirm with more than one source than just x ray assuming that x ray film was flipped. They glance atleast for a minute on the clinical details before they touch the knife. Patients are not products waiting in assembly line. If there is any failure in any of the life support system or operating machines, that could be a process mistake, but not when a surgeon has no seconds to check the clinical details to confirm. An intelligent surgeon all along who does the mistake of not checking before starting, is actually dumb no matter how he has been performing all along, because patients are not products of assembly line to take it for granted.

Even in mass surgical procedures for simple cataract removal with huge waiting lines in hospitals, they do ensure and have to ensure especially for bilateral organs.

Be careful with assembly line analogies – as assembly lines deliver better quality than hospitals.

Exactly..because the precision is mechanically controlled in assembly lines and that is exactly why same process control may not work in hospitals. In assembly lines, if something goes wrong, the loss is comparably lesser than the loss from a surgeon open the wrong side of the cranium or operating a wrong eye or removing a wrong organ that is in functional form. It will cost the hospital more, besides possible career black mark to the surgeon, other than the human suffering. So ultimately, in hospitals where there is more human intervention, process control is also dependent on humans, no matter how much of an expertise the doctor has, he has no choice than being careful at all times, because each patient is unique and different. My analogy is to bring the contrast.

That’s all the more reason to have good process in healthcare – so much is at stake. No human can be “careful at all times.” That’s why we need management system controls – things like checklists AND a culture that ensures they are always used, that people aren’t rushed, that people behave properly, that people have a way to speak up when they see a problem, etc.

It’s not as easy as mechanical error proofing, but assembly lines are also social-technical systems with human beings… don’t assume how easy manufacturing quality is.

Patients are indeed on a “production line”, now it is a very variable one with little control of inputs. When the production line is over burdened we don’t rush or make mistakes. We get more resources, work overtime, or delay production. Now people are difficult to mistake proof, but better process with interactive confirmation by more than one individual is mandatory. I find that hospitals don’t have folks who understand process control, but rather are doctors. Standardized process can improve performance and generate many benefits as long as we use it.

Here’s an article from the BBC about 750 “never events” in the British NHS:

http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/health-22366147

In one case, a woman had a swab left inside her. Then, in the second surgery to repair the situation, they left a 7-inch forceps inside!

“My initial reaction was ‘no’. They can’t do it twice,” she said.”

The NHS says the risk of a “never event” happening to you is one in 20,000.

What can fix this? Culture:

It’s not just understanding the RESPONSIBILITY — it’s having a system that allows everybody to work effectively.

I have known cases where the surgeon accidentally dropped the intra-ocular lens (IOL) in the vitreous chamber of the eye and could not remove it, but placed another IOL intact. Can you imagine the plight of the patient and some of these cases are not even reported, to protect the hospital itself, where they come to an agreement with the patient within closed walls, later if anything happens.

That makes me ask why a surgeon would do such a thing? If you’ve made a mistake (humans drop things… we aren’t perfect), don’t compound it by CHOOSING to not report the problem. Dropping something is not a choice. Failing to report the drop IS a choice.

I totally agree that the work culture matters a lot in providing efficient patient care ultimately.

The main problem with health care settings is the variability existing among the health care provider themselves in providing quality care. While some take personal interest and care, some dont.

I agree with you totally that there are no easy answers to these challenges. Its more of an individual cultural change that alone can bring a mass change in the work process.

There has to be a collective effort consciously.

Virginia Mason Medical Center is a great example of a health system that’s using systematic training methodologies to help improve the reliability of care – good for the patients and it doesn’t put staff members in a bad situation:

http://virginiamasonblog.org/2013/04/24/training-within-industry/

Thank you Mark for bringing attention to this situation. These events are tragic. People need to be aware how often human errors or process errors happen, so that they can be corrected or eliminated.

[…] In the case of serious surgical errors, it’s apparent how warning signs would probably not be effective. If they were, we could just post a bunch of signs everywhere, including one that says, “Warning! Don’t operate on the wrong side of the patient’s brain” – as errors like this occur all too often. […]

Judie’s ordeal was simply high-way robbery, murder. I don’t buy overbooked ER’s, overtaxed systems, etc. What I do know is that everyone thinks they are a doctor in a hospital. It’s time to have a serious wake-up call. There’s a lot of humbling to be done.

I like the NHL approach. If you can’t score goals you are sent back to the Pee-Wee’s. Jack Kitts has a lot of work to do. His insane annual bonus should be based on how many actual, measurable, tangible people were saved. Enough with the politicking get some work done or move aside.

I scream every time some “walk the fence or middle of the road” person starts talking statistics in an attempt to sound smart or look reasonable. This is so OTTAWA, let’s not rock the boat. I witnessed first hand the Medical Coroner walk-in and leave 5 minutes later.

When it takes 6-7 months to obtain a report, someone’s butt is being covered. In addition, the person in authority does not want to commit. Hence, another butt is being covered. This is starting to stink.

I personally had surgery in Cornwall 3 years ago to repair a grade 5 shoulder separation. At first, I went to the Ottawa Hospital. The doctors were on vacation and scheduling was up to 6 months later. I got fixed by Dr JF Lemoine within 8 days. The Ottawa Hospital called me 6 months later, but I had already had my second surgery to remove the pins, screws and plate.

I’ve been hearing about hospital issues for the last 30 years. Guess what folks, they are still there

In healthcare, quality of care is more than just a CONCEPT! It’s essential for patient well-being and ultimately survival. In reading the detailed account of events that failed Judy, Mel and the rest of her family, it became obvious that even in today’s world with abilities that we possess through technology, the rigors training (academic and hands-on training), amongst other critical knowledge areas that there is still a significant level of deficiency that still exits in the delivery of quality of care in the Canadian healthcare system.

Understanding that the definition of ‘quality of care’ means there may be as many definitions as people, and differing definitions can and will lead to different priorities and different goals, depending on the perspective of the individual i.e. patients, their families, healthcare providers, regulators, etc, I am confident that all would agree quality of care was missing in this heartbreaking and devastating instance. The health care system has the ability to learn much from errors and near misses, and those learning opportunities need to be identified and capitalized on at the time they are realized. Unfortunately, in our society, it is difficult to create a blame-free environment without incurring legal liability for negligence. We need to continue to evolve and overcome this perceived threat.

Can you imagine losing your wife? mother? friend? as Mel and his family did with Judy… My hope is that the dedication from Mel and his family will result in a set of recommendations that will be considered at all levels within our healthcare system and ultimately contribute to invoke needed change .

God Bless Judy and God Bless change in our healthcare system.

Recommendation: The Ministry of Health should create a Center for Patient Safety within the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. The Center for Patient Safety should:

 Set the national goals for patient safety, track progress in meeting these goals, and issue an annual report to the Minister of Health on patient safety.

 Develop knowledge and understanding of errors in healthcare by developing a research agenda, funding Centers of Excellence, evaluating methods for identifying and preventing errors, and funding dissemination and communication activities to improve patient safety.

Recommendation: A province-wide mandatory reporting system should be established that provides for the collection of standardized information by provincial governments about adverse events that result in death or serious harm (if this doesn’t already exist). Reporting initially should be required of hospitals and eventually should be required of other institutional and ambulatory care deliver organizations.

Recommendation: Ontario should pass legislation to extend peer review protections to data related to patient safety and quality improvement that are collected and analyzed by healthcare organizations for internal use or shared with others solely for purposes of improving safety and quality. Set Performance Standards and Expectations for safety.

Recommendation: Performance standards and expectations for healthcare organizations should focus greater attention on patient safety.

 Regulators and accreditors should require healthcare organizations to implement meaningful patient safety programs with defined executive responsibility.

 Ministry of Health should provide incentives to healthcare organizations to demonstrate continuous improvement in patient safety.

If patient safety and healthcare quality is the moral and right thing to do, why should organizations need “incentives” to do work on patient safety and continuous improvement? Is “lack of incentives” really the cause of our poor state of quality and safety?

Hi Mark,

I’m defining Incentives as “what organizations put in place – above and beyond straight salary – to get people to do their jobs.” The definition is only partly tongue-in-cheek. As an example the most successful and progressive organizations in the world increasingly are embracing performance-based compensation and incentive programs. Why? Because most of the time, they meet a need and offer tangible benefits.

The need might be strategic: to attract and retain high-caliber professionals, manage risk from rising competitive pressures or lift the levels of productivity and performance across the organization. When I say will say that ‘incentives’ I’m not suggesting financial incentives in fact in not suggesting that I have a solution to what that would look like, but what I am saying is that motivating people to do better whatever it is they do requires some sort of ‘pay-off’ or incentive.

Plenty of broken and dysfunctional organizations have “performance”-based compensation and incentive programs too. General Motors, for example, had many “pay for performance” schemes on many levels.

It seems that organizations, in healthcare especially, do a lot to drum the intrinsic motivation out of people and then try to replace it with extrinsic rewards and the threat of punishment.

Check out the work of W. Edwards Deming or the more recent book “Drive” by Daniel Pink (my podcast with him here: https://www.leanblog.org/107).

Many people strive to do better because 1) they are motivated to do what’s best for patients and 2) they enjoy improving. If somebody needs a financial reward to improve healthcare quality and safety, they are probably in the wrong business.

[…] The headlines are out there, everyone has heard a story from someone they “know”, and Mark has blogged about surgical errors as recently as last year. I was pleased that, in several process steps prior to my surgery, I was asked by multiple people […]

Comments are closed.