In recent years, there's been a movement away from having first-year residents work such long grueling hours – 24 hour shifts or longer, multiple days in a row on call, etc. The idea was that fatigued residents were making poor decisions and mistakes, leading to patient harm. It seems reasonable, since who performs really well when tired? And, that includes nurses at the end of a 12-hour shift.

In recent years, there's been a movement away from having first-year residents work such long grueling hours – 24 hour shifts or longer, multiple days in a row on call, etc. The idea was that fatigued residents were making poor decisions and mistakes, leading to patient harm. It seems reasonable, since who performs really well when tired? And, that includes nurses at the end of a 12-hour shift.

A recent study suggests that error rates have gone UP with the shorter resident shifts… can we really conclude that from the available data?

As summarized on the TIME blog: Fewer Hours for Doctors in Training Leading to More Mistakes.

First off, we have to be careful about confusing correlation and causation. Does fewer hours LEAD TO more mistakes? Some argue it does, since the residents are receiving fewer hours of training, there are more handoffs, and hospitals aren't adding more residents to pick up the gap left by shorter shifts.

From the article:

In 2011, those hours were cut even further, but the latest data, published online in JAMA Internal Medicine, found that interns working under the new rules are reporting more mistakes, not enough sleep and symptoms of depression. In the study that involved 2,300 doctors from more than a dozen national hospitals, the researchers compared a population of interns serving before the 2011 work-hour limit was implemented, with interns working after the new rule, during a three-month period. Those in the former group were on call every fourth night, for a maximum of 30 hours, while the latter group worked no more than 16 hours during any one shift. They gathered self-reported data from on their duty hours, sleep hours, symptoms of depression, well-being and medical errors at three, six, nine and 12 months into their first year of residency.

“In the year before the new duty-hour rules took effect, 19.9% of the interns reported committing an error that harmed a patient, but this percentage went up to 23.3% after the new rules went into effect,” said study author Dr. Srijan Sen, a University of Michigan psychiatrist in a statement. “That's a 15% to 20% increase in errors — a pretty dramatic uptick, especially when you consider that part of the reason these work-hour rules were put into place was to reduce errors.”

Let's reflect on the scale of the numbers for a moment — roughly 20% of interns REPORT committing an error that harmed a patient. How many interns did NOT report such harm, given healthcare's problem with the underreporting of errors? There's bound to be a tendency to underreport even in an anonymous survey, as pride and one's unwillingness to admit errors coming into play.

The study, as broad as it was, was a simple before and after study. That means TWO data points. Two data points do not make a trend (as I've written about before, in the context of consulting firm before and after studies).

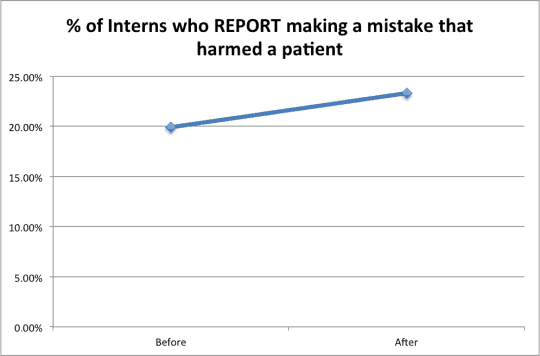

Here is the comparison in a simple two-point chart:

If you're somebody who was pre-disposed AGAINST the shortened work hours, this data (the two data points) would certainly seem to “prove” your case.

All we know is that the second data point is higher. We don't have a longer time series of data that would allow us to evaluate a trend or make a more statistically meaningful conclusion through the use of a Statistical Process Control chart (see a webinar I did on this topic for Gemba Academy).

If we viewed each data point like a political poll, they would report a margin of error, such as +/- 2%. With the above patient harm data, if the “Before” number was understated and the “After” number was overstated, then it's POSSIBLE that the level of patient harm is flat or that it's even decreased a touch with the shorter intern hours.

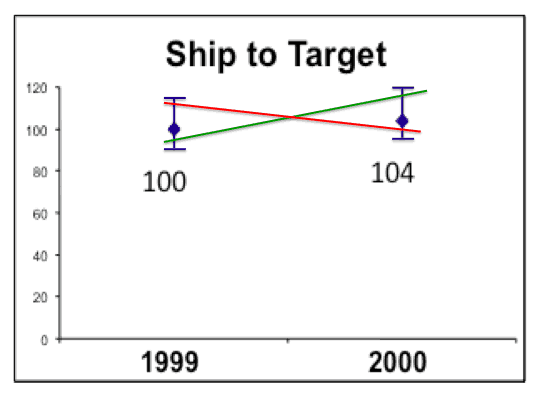

I make a similar point in my SPC talks about simple year-on-year before/after data from my time at Dell Computer:

Looking at a reasonable margin of error (based on monthly variation, which I had access to) in this normalized “Ship to Target” number, it's possible “the number” went up or it went down. The annual number of 104 for the year 2000 wasn't definitively higher than the 100 value for the year 1999. Yes, 104 is higher than 100, but not necessarily, when you consider the variation in the data. Showing two data points often simplifies things in a number of ways. The same idea applies to the patient harm data.

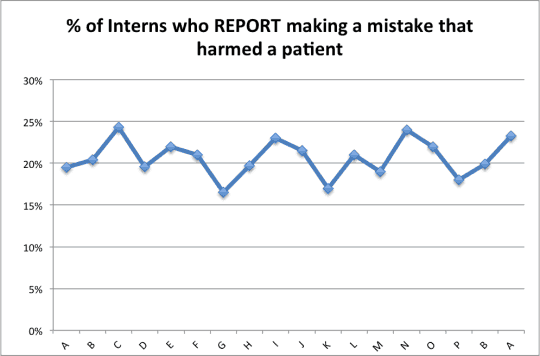

It could be that the “pretty dramatic uptick” (as it was called) in the data is really just part of noise in a fairly stable system. If we had more studies looking at 3-month periods over time, we might see a chart like the one below (with TOTALLY made up data, other than those two 19.9% and 23.3% data points, the last two in the chart):

That jump between the last two data points (from 19.9% to 23.3%) might be “pretty dramatic” but it might also not be unusual. It could be “common cause” variation in a system. Without more data, we don't know. I'd be VERY curious to see the next data point, if this was studied for another three months. If the 23.3% data point were part of the noise in the system, the next data point could be just as likely 18%…

People seem to be making a “special cause” assumption – shortening the hours resulted in higher reported error rates, or at least the headline assumes that.

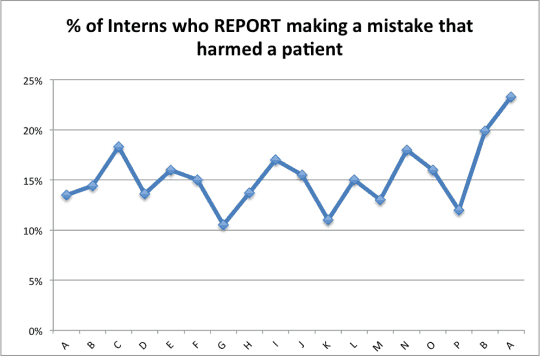

With different made up and assumed data, the chart could look this… which might imply a special cause data point that's at least a bit out of line with the history:

There COULD be higher reported error rates… but let's also keep in mind that hospitals, medical schools, and the broader healthcare community have been placing much more emphasis on not covering up errors or problems — more honesty and transparency and less “shame and blame” punishment.

Higher REPORTED rates of harm doesn't mean more ACTUAL HARM is occurring.

So we do we know from this study? We know that shorter working hours doesn't seem to be a panacea, as the interns aren't reporting benefit:

Although the trainees working under the current work rules spent fewer hours at the hospital, they were not sleeping more on average than residents did prior to the rule change, and their risk of depression remained the same, at 20%, as it was among the doctors working prior to 2011.

Another possible cause of the possible increase in reported harm – handoffs.

Another source of errors came as one intern going off duty handed his cases to another. With fewer work hours, the researchers say the number of handoffs has increased, from an average of three during a single shift to as many as nine. Anytime a doctor passes on care of a patient to another physician, there is a chance for error in communicating potential complications, allergies, or other aspects of the patient's health; that risk is boosted when the transition occurs several times over.

If handoffs are error prone, then I'd say we need to FIX handoff communication process. We shouldn't have a knee-jerk reaction to doing fewer handoffs. We can do them better, with Lean and Six Sigma process improvement methodologies.

I guess I'd agree with the conclusion of the piece (which is far less definitive than the headline):

Figuring out the right balance between humane work conditions that promote the best learning environment for residents and the highest quality of care for patients may still be a work in progress. More research is needed to pinpoint what's driving the uptick in medical errors and determining the best strategies for improving resident training to bring these rates down.

And I'd add, “Be careful about drawing strong conclusions from just two data points!”

Also worth reading are the comments to the post, including the stereotypical doctor response (generations have been trained this way, I did it, and this generation is soft) and allegations of lying about the number of hours worked to keep under the regulation limits.

I'll be blogging tomorrow about other examples of people fudging data to make things look good – in education and in healthcare.

What do you think? Please scroll down (or click) to post a comment. Or please share the post with your thoughts on LinkedIn – and follow me or connect with me there.

Did you like this post? Make sure you don't miss a post or podcast — Subscribe to get notified about posts via email daily or weekly.

Check out my latest book, The Mistakes That Make Us: Cultivating a Culture of Learning and Innovation:

Senior MD friends of mine observe that, fundamentally, the new rules guarantee that new docs have obtained much less breadth and depth of experience by the time they hit the streets than in the past. Which tells me that as a consumer, I will be subject to green doctors who previously would have still been under “adult supervision” let loose to practice on me with essentially no oversight, let alone self-reporting of errors. Is anyone looking at the big picture?

Thanks for your comment. I’d be curious if these senior doctors have data to back the claim that the younger doctors aren’t as well trained – or is that an opinion? It’s got to be possible to provide good training or better training in less time if the training methods are improved. I’m glad there are doctors and medical schools looking at better ways of training doctors, rather than just spending more time on it.

Some of the complaints from older doctors sound similar to fraternities defending a tradition of hazing… we worked long hours and put up with abuse from the attendings, so the younger docs should do that too. Is there evidence that working 36 hours straight really makes you tougher and calmer under pressure to then be able to make better decisions?

I’m just an engineer, so I’ll leave that to innovators in the medical schools.

I can tell you the two data point comparison doesn’t convince me the current work rules make things less safe.

In the future, we CAN sadly look forward to increased shortages of physicians. There’s data to back up that statement.

I confess I haven’t demanded their data. It was pretty basic math: if in the old system they would have seen an average of X cases by the time their medical training was completed, it will now be X times a fraction of that, and the fraction as I recall it was not 0.999, more like 0.6 or 0.7 (I could be off but you get my point.)

So of course the new MDs should be making fewer errors if they are getting fewer opportunities to do anything at all.

New MDs graduating with significantly less experience than before is a problem. To your point and that of Anonymous, the med schools need to creatively lean out their training programs to make room for more actual learning with the reduced work time and resources, and that keeps patients safe.

PS: I never heard even the hint of, “if I had to do it, so should they,” from the senior MDs to whom I was referring.

The number of patients is roughly the same, so the “opportunities for error” are probably the same. If there are fewer intern hours, they might be rushing their rounds and evaluation, which could lead to poor quality decisions… it’s not my gemba, but I don’t trust the simplistic reporting of the two data points.

Maybe the answer is shorter hours but longer internships. I can’t believe that forcing information into a tired mind helps much. The number of hours in a day is not the only variable that can be adjusted.

One of the likely causes for the increase in reported errors identified by the researcher was more frequent hand-offs. Hmmmm. If that were true, should hospitals make nurses, hospitalists, and intensivists work longer shifts in order for better outcomes. I think quite the opposite is true where there are numerous studies that suggest even 12-hours shifts cause more errors. So, if in fact more hand-offs are the cause of more errors then is the problem how hand-offs are done and not the length of the shift?

True enough, shorter shifts over the same amount of time results in less training. My observation of one rotation of a residency program is that 35% of the time the residents were waiting for a response from the attending physician before they could proceed. The point is that medical education has a lot of opportunities to improve the density of learning but this will require some significant rethinking of the whole process.

Mark,

I think I would frame the question differently. I would not look at this as a trend question. I would look at it as a question of comparing two populations, as in “Does population A with access to clean drinking water have a statistically significantly lower disease rate than population B without access to clean water?”

But to the point of higher defects, it doesn’t pass the smell test. It could simply be that the non-fatigued interns were more aware of the mistakes they were making. As you mentioned, self-reporting in this case could be adding bias.

Good post, Mark. Two comments: 1) In one of my jobs in my early career as a clinical laboratory scientist, I worked on-call at a small community hospital that staffed its emergency department with residents who worked 48 and 72 hour shifts. There was only one MD working at any given time. Depending on the ED volume, they might be extremely well rested or running on pure adrenalin. I saw many mistakes happen when they were tired. Fortunately, most of them had the presence of mind to ask those of us supporting them to keep an eye out for possible mistakes due to how tired they were. But what a terrible position to put anybody in — whether patient, physician, or support staff. I’m not sure how much has changed since then, but it was a huge concern of mine.

2) I wish to goodness that healthcare would refuse to make ANY data about errors public. I’m serious. The only way healthcare staff will begin reporting the truth so we have good data to work with is if there is NO ramification for reporting negative data. Any time information is made public, there are ramifications. I realize that this is counter to my typical “we need transparency” mantra, but I believe this is one very important exception to the rule we need to adopt. When I work with hospitals to reduce medication errors, I go to great lengths to prepare leadership and staff alike that one of the metrics for measuring success is seeing the number of reported medication errors going UP. It’s a challenging journey, but a noble one worth taking. Same goes for physician errors. The only way to get to root cause is to get good data. Getting good data requires us to remove all barriers to getting good data. We have a lotta work to do in that regard.

1) I agree we shouldn’t be putting people in bad situations

2) I think the proper countermeasure is eliminating the ramifications, not eliminating the sharing of data. Patients have a right to know which organizations are most likely to harm or kill them and that data is sorely lacking. More transparency doesn’t HAVE to lead to more punishment or more ramifications.

There’s a lot of work to do.

While I agree that removing the ramifications is goal #1, until that’s done I vote for keeping the data private. The media and patients alike have no appreciation for the complexity involved in moving the needle and making the data public adds kerosene to a fire that needs water.

That said, the only way I’d accept “private” is if the org was VERY AGGRESSIVELY working to move the needle. Private is the reward for orgs who are “getting it” and doing something about it. Public humiliation should still exist to create the pressure and sense of urgency to shake complacent hospitals from their stunningly comfortable perches.

Well, the healthcare status quo generally agrees with you. Keeping data private/hidden hasn’t really helped. “Stunningly comfortable perch” is a great way to put it.

Cause and effect is important to consider. Is the lack of movement on the issue due to private data or just complacency?

I think the lack of transparency enables the complacency.

It’s a shame that we have to use data to shame any person or institution into taking appropriate action to save lives. But I still think that, once an organization begins to take serious steps to reducing errors, the public will NEVER understand nor tolerate numbers going up. There’s the conundrum. The numbers HAVE to go up to resolve this issue.

Sadly, the public isn’t paying attention. Or they fall into the usual blame-and-shame game (somebody must be punished!). There’s really nothing more dangerous that we might do in our lives than be admitted to the hospital. That’s not hyperbole.

The airline and airplane industries are very transparent on safety issues as a necessity of survival.

People have a choice to fly, but no alternatives for gall bladder surgery. Maybe this is the reason that poor quality is acceptable.

Karen makes a good case for not being transparent. I think this is largely due to a pervasive shame and blame culture internal to most healthcare organizations. What’s the countermeasure for blame and shame?

Perhaps flogging??? All kidding aside, it’s a VERY deep-seeded problem and why a whole lotta psychology has to be taken into account. Unless you’ve spent decades in the healthcare industry, it’s very difficult to fully appreciate the complexity–politics, litigation mitigation, financial ramifications, personality types of those called to serve, power structure, etc. etc. etc. The most “common sense” thinking around this issue may be, in fact, quite counter-intuitive.

This data strikes me as incomplete. From how I’m reading your post, the data is whether Intern A, B, C, etc. each self reported making at least one error that harmed a patient. It doesn’t sound like this data reflects the overall quantity of errors made before and after the change in policy, if so, then it is useless as a metric – people without systematic help will make errors. You’re only asking if they’re error prone not whether you’ve helped the error prone make fewer errors by giving them needed rest time.

I’m hoping that a more alert and well rested intern would make fewer total errors by learning from the few they do make (and report as 1 data point) versus the potential for a very tired intern to make a larger number of errors and still report as 1 data point.