Paul Levy, the former CEO of Boston's Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, is a long time friend of mine and this blog (read his ongoing blog here although he's no longer “Running a Hospital”). I've been meaning to blog about it for a while… it's still a relatively new book that Paul has published (a few months ago) called Goal Play!: Leadership Lessons from the Soccer Field (available in paperback and Kindle formats).

Paul weaves together management lessons from his previous industries, including government and healthcare, with lessons from coaching youth soccer. Books like this run the risk of being corny in making analogies between sports and something in work life, but the girls' soccer analogies are used smartly to tee up the points of each chapter — I've really enjoyed reading his book.

There's a great story in chapter 1 about organizational inertia and the dreaded phrase “it's always been this way.”

The Boston Parks and Roads Commission had just assumed that it just had to be that one truck a week would hit the Mass Ave bridge that goes over Memorial Drive (sorry, “Mem Drive” for the locals) and Storrow Drive. The new leader of the Commission asked why it was inevitable and unchangeable that one truck a week would hit the bridge, causing delays, repairs, and congestion.

He was given a lot of answers about how efficient the process of cleaning up after this weekly accident had become. I guess that's example of doing the wrong thing better — or not doing the “righter” thing… actually preventing such accidents.

To his credit, the leader asked what they could do to actually prevent the accident.

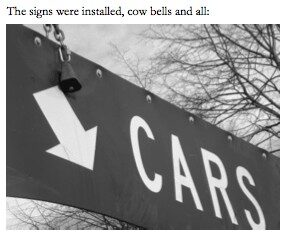

While being told it wasn't possible, he pushed and prodded until they found a clever countermeasure that worked – it involves rubber signs and cowbells (!). The cowbell provided an auditory warning that the driver had hit the rubber sign… as an indicator that they would hit the less-flexible bridge if they didn't stop.

The number of accidents fell from one a week to just one a year.

There are, of course, great parallels to leadership and improvement in healthcare.

Is it just inevitable that a certain number of patients are going to get hospital-acquired infections? Or fall? Or have the wrong side operated on? Do we need to just get better about cleaning up the problems (or apologizing for them, as some Massachusetts hospitals are doing)? While apologizing for an error might be the downright decent thing to do (better than lying or stonewalling), shouldn't we do more to PREVENT healthcare harm?

Leaders like Paul Levy (and Paul O'Neill, listen to my podcast with him) challenge organizations to work toward perfection as the goal. We can't settle for “the way it's always” been.

What do you think? Please scroll down (or click) to post a comment. Or please share the post with your thoughts on LinkedIn – and follow me or connect with me there.

Did you like this post? Make sure you don't miss a post or podcast — Subscribe to get notified about posts via email daily or weekly.

Check out my latest book, The Mistakes That Make Us: Cultivating a Culture of Learning and Innovation:

Nice to see cowbells gaining constructive use other than ’70’s rock classics (see “Don’t Fear the Reaper,” Saturday Night Live, More Cowbell sketch).

Seriously, though, an error-proofing method was also in the news this morning. A young father had forgotten his toddler in his car for over 2 hours – I’m sure you’ve heard of this happening before – and passersby eventually noticed. The legal authorities were talking about a court appearance for the father, blaming and shaming him to death. When the broadcast transitioned to the weather, ABC Weather Director Sam Champion offered a good method to PREVENT this from occurring, which is for caregivers (parents, whomever), to place important items that are required for your next stop next to the child in the seat, such as briefcases, laptops, iPads, etc. Kudos to Sam for offering an error-proofing method as opposed to the usual blame and shame scenario, and not accepting that, “this will always happen.”

Good example of error proofing. Not having children, I won’t judge somebody who forgets a baby.

When leaving home, I put items I need to remember either next to my iPhone or my car keys… pretty effective (if I remember to place things there).

It’s an interesting commentary that somebody is less likely to forget an iPad than a baby! You’d think the likely problem would be in reverse… I often forget my iPad, so I put it next to the baby…

In the case of the father (or medical situations) it’s easy for people to judge and say “well, they shouldn’t have done that.” It’s called “human error” for a reason – because we’re human and eminently fallible… hence the need for good system design.

Mark – interesting point you made on being less likely to forget an iPad than a baby. I believe, but am not sure, that the child’s mother normally takes the child to daycare, so it wasn’t a routine for the father to do this. The habit he had been used to was just to grab his work items and go into his office – his child wasn’t normally with him. Knowing that lean thinking involves developing the right habits to make work flow, the father’s normal “right habit” was to simply grab what he needed for work and go in. Taking the child to daycare was an exception. And, if the child wasn’t making any noise, and was in the back seat, as child seats should be, the father’s habit of grabbing only his work materials and going into the office just took over…

Once when my children were gradeschool age, both my wife and I were at some community baseball fields watching our kids play ball and play on some playground equipment. Since we had arrived in separate cars (not the norm for us) we both left for home thinking the other had the kids with them. Neither of us did. Thankfully it was a quick drive back! “Normal” for us was to be at our kids’ activities in one car, making forgetting the kids very unlikely. Arriving in 2 cars threw us off.

That completely makes sense that being thrown out of one’s normal routines causes mistakes. After moving to San Antonio and still having things not settled in, I started making travel mistakes I don’t normally make – forgetting my GPS unit before leaving for a client trip, etc.

I wonder how many medical mistakes have “we were thrown off of our normal routines” as at least a contributing factor? Things like delays, new team member, other causes of confusion or fog?