Last weekend, I watched a show on the Smithsonian Channel that was an interesting contrast to the CNN show I blogged about yesterday (“A Lean Guy Watches “CNN's 25 Shocking Medical Mistakes“). The Smithsonian show was about aviation safety: “AIR DISASTERS: FATAL DISTRACTION” about the famous 1972 crash of Eastern Airlines flight 401, the first crash of a “widebody” jetliner, a Lockheed L-1011 Tristar 1.

As with many medical errors, this crash was eminently preventable. The aviation industry arguably has done more to learn from its mishaps than has healthcare (though this is changing?). Rather than blaming an individual “bad pilot,” the problem solving (and countermeasures) focused on systems and prevention.

Long story short, the plane crashed in the Florida Everglades after being sent into a holding pattern around Miami at 2,000 feet, as the flight crew (three plus a dead-heading pilot) all investigated a burnt out cockpit indicator. They weren't sure if the nose landing gear was fully engaged – it was a problem with the gear, the light, or possibly both.

The autopilot functioned properly (it was considered very advanced for its time). They knew it worked fine because investigators actually installed the autopilot from 401 into a different plane to test it. This was part of their methodical investigation to rule out possible causes.

They were lucky to have the black box and they were lucky the pilot survived long enough to tell his story to investigators.

As aviation safety expert John Nance (author of the excellent book “Why Hospitals Should Fly“) was on the show talking about the system errors that led to the crash.

Everybody in the cockpit was working on the light… nobody kept their sole focus on flying the plane. That was a lesson learned. As Nance said, “they weren't trained properly.” In hindsight, it seems like common sense that SOMEBODY needs to focus on flying… but this was a new situation and they had a bit too much faith in the advanced autopilot system of Lockheed.

So, while the captain was distracted (and sort of arguing with the rest of the crew about troubleshooting the light), the pilot turned and (they think) bumped the switch that disengaged the auto pilot. So the plane started losing altitude and they didn't notice until it was too late to pull up. The pilot didn't hear the warning chime (which was confirmed to be working) because the chime occurred when the pilot was yelling at another crew member (investigators know this from time stamps on recordings and the black box).

Ironically, the autopilot system was designed to be EASY to disengage – to save time. Nance pointed out that this was, again, a system issue because the pilots weren't trained to avoid disengaging the autopilot. Nance said, “the way we handled things in the cockpit wasn't safe.

This incident, along with the famed Tenerife airport disaster, lead to the development of Crew Resource Management training – a method has dramatically improved airline safety (and is being used increasingly in healthcare today).

As Nance discussed, two key points of CRM included:

- Specific delegation of tasks in the cockpit

- A climate with less fear of the captain

It's cultural and systemic improvements like this that make me feel pretty confident when flying. In fact, I'm writing this post on a flight.

While CNN's Elizabeth Cohen kept recommending that patients basically inspect and double check the work of hospitals and physicians (a notion I think is really silly and unfortunate), I don't recall John Nance or other experts recommending that I ask the pilot if they've done their checklists when I board. I'm not admonished to ask if the first officer is afraid to speak up to the pilot. The aviation world has improved and managed its systems in a way that healthcare is still learning.

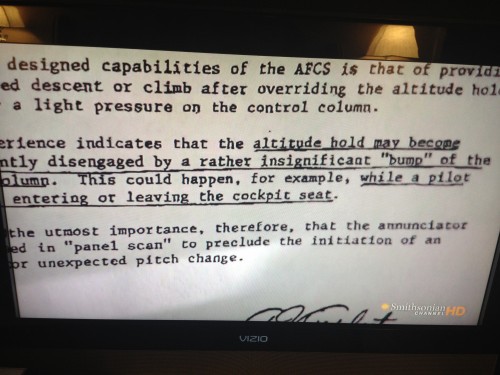

One thing from the aviation show that reminded me of healthcare, unfortunately, was one of the aviation world's reactions to the Eastern disaster. They (the airlines and the FAA?) posted a bunch of memos for pilots saying that they should be careful about not bumping the autopilot, as shown below. A better system fix would be to redesign the autopilot switch/button — which I assume they did over time.

Healthcare still tends to rely a bit too much on “be careful” signs, as I've blogged about in a side project and done keynotes about.

You see signs reminding staff to not enter the wrong dosage into a badly designed pump. I've seen signs reminding staff to double check medications… to not forget to wash their hands. These signs and reminders aren't the most effective way to prevent errors.

Safety is the result of culture and systems. Highly trained professionals (like pilots, nurses, or doctors) are a good start. But asking good people to be careful isn't enough to ensure high reliability and safety).

Please scroll down (or click) to post a comment. Connect with me on LinkedIn.

Let’s work together to build a culture of continuous improvement and psychological safety. If you're a leader looking to create lasting change—not just projects—I help organizations:

- Engage people at all levels in sustainable improvement

- Shift from fear of mistakes to learning from them

- Apply Lean thinking in practical, people-centered ways

Interested in coaching or a keynote talk? Let’s start a conversation.

If you go over the cockpit transcripts from Sully’s landing on the Hudson, you will notice a key learning from the Eastern crash woven right into his case. You’ll hear Sully say, “My airplane,” and you’ll hear F/O Skiles respond, “Your airplane.” Skiles had been the pilot in command at takeoff, but when Sully determined they were in trouble, the FIRST order of business was to assign the task of flying the airplane–in this case, to himself. You can draw a straight line from the Eastern everglades crash to this exact moment. Difference between aviation and healthcare? Aviation learns.