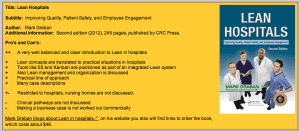

Dr. Jaap van Ede, a Dutch journalist and researcher on business improvement methods (such as Lean, Six Sigma, TOC, QRM, and TPM), has posted a summary and review of my book Lean Hospitals. The review is titled “A well-balanced introduction to Lean in hospitals.” His summary can be viewed at left (click for a larger view) or visit his website for the entire review.

One piece of constructive criticism is that I didn't lay out a clear business case for Lean, or at least directly so, in the book. Fair enough, and I'll address that here in this blog post.

I appreciate the kind words, including:

What I liked in particular is the practical line of approach. There are many inspiring examples, but Graban explains that you should experiment – of course without jeopardizing the quality of the care – to find out what works in your ward, laboratory etcetera. Typical Lean objectives like zero waste and creating a One Piece Flow should only serve as a direction for improvement, and the application of tools like 5S should not be exaggerated. It should always be kept in mind that the primary goal is more value for the patient. Lean tools are useful if these solve problems and reduce waste, with interfere with patient care.

But, Lean thinkers tend to focus on the gap between an ideal product or service and the actual condition.

Dr. van Ede writes:

There were only two things I missed in this well-written book: The concept of creating clinical pathways for patients with similar symptoms, and making a business case for Lean.

I tried to make conditions between patient pathways and the Lean view of value streams. For introductory Lean efforts, the focus is usually on mapping the current state, looking for opportunities to improve. Creating new clinical pathways might be part of the future state creation… but I can see where my book probably does a better job looking at the current state than it does making any recommendations about better future states.

On the business case question, this is a difficult one to address in a book that is read in so many countries (and is being translated into eight different languages). The “business case” in healthcare so often depends on the payer system and the dynamics in a particular country. Are “cost savings” realized by the healthcare provider or the payer? Are there truly opportunities to increase revenues by increasing throughput and capacity if the country pays a fixed sum based on population numbers?

I do try to share a wide range of benefits and data in the book, including:

- Quality improvement (whether traceable back to resulting cost reductions or not)

- Patient safety improvement (again, maybe tied back to cost)

- Cost reduction

- Revenue increase / capacity increase

- Prevention / reduction of capital spending

- Improved flow / reduced length of stay

The article shares this data:

[CEO Dr. Patricia] Gabow estimates that utilizing lean has yielded up to $127 million in financial benefit without the organization having to lay off any of its 5,400 employees.

While the articles, including this one, usually cite quality and patient care improvements, it's the cost savings that gets the headlines. Healthcare is far too expensive in the United States, so that's understandable. The cost of care is increasing more quickly in the other first world countries more quickly than they would like (and often rising to a point that seems unaffordable).

But I'd encourage the business case to take a more balanced view, such as the Lean / Toyota mantra of SQDCM:

- Safety

- Quality

- Delivery (meaning waiting time or access to care)

- Cost

- Morale

The general public knows costs are too high. What's less widely known is that quality, safety, and access can be dramatically improved through Lean… and improving staff morale (by engaging them in improvement) is often the path for getting there.

How does your organization make or measure the business case for Lean? Is it all about dollars (or your currency) or is it a balanced group of measures?

Thanks again for the review — Dr. van Ede's websites are www.procesverbeteren.nl (Dutch) and www.business-improvement.eu (English).

Please scroll down (or click) to post a comment. Connect with me on LinkedIn.

Let’s build a culture of continuous improvement and psychological safety—together. If you're a leader aiming for lasting change (not just more projects), I help organizations:

- Engage people at all levels in sustainable improvement

- Shift from fear of mistakes to learning from them

- Apply Lean thinking in practical, people-centered ways

Interested in coaching or a keynote talk? Let’s talk.

Join me for a Lean Healthcare Accelerator Trip to Japan! Learn More

But it does raise an important issue in terms of healthcare. The business case isn’t necessarily as strong as it is in other environments, and the reason, as you point to, is the payer system. The system isn’t set up as a healthcare system, but an unhealthy-care system. There are low incentives to keep people healthy, or to get them healthy. Profitability depends on doing more to patients. It’s not that people are acting unethically (although that’s true too), it’s just that the incentive is a bit inverted. Although, this shouldn’t prevent anyone from doing what they know to be right. It just makes it harder to get everyone on board and aligned.

Jamie F

You’re right about those disconnects, Jamie. Healthcare is still trying to wean itself off of a piecework “fee for service” model. In this model, let’s say Virginia Mason Medical Center reduces the waste of overprocessing by not automatically giving diagnostic imaging (CT/MRI) to every E.D. patient who presents with back pain. The medical evidence shows that physical therapy is better for the patient and it’s less expensive. The payers reap the benefits of that improvement that was initiated by the Lean work of VMMC. So, sadly, there are cases where a Lean hospital doing the right thing gets hurt financially.

It will be interesting to see if new approaches in the U.S., such as “accountable care organizations” (ACOs) will help encourage that coordination of “healthy care.”

John Toussaint has blogged about this, including:

http://www.createhealthcarevalue.com/blog/post/?bid=260

If “unhealthy care” is heavily non-value added from a broad social perspective, what would happen to these massive institutions if (by some miracle!) we were to get it right and live healthier lives and deploy healthcare resources more effectively? There would be some pretty big changes.

On the one hand we bemoan the cost of healthcare and on the other we love it as a growth sector in the economy! Communities love the economic activity that comes with major healthcare centers. Genuine improvement will be disruptive.

So, to your original question, maybe we shouldn’t be talking about a business case for lean in healthcare here in the U.S., given our current system of incentives and payers, but a social case – a case for the good of society and the individuals needing care.

I don’t see how “massive institutions” lead healthier lives… isn’t that an individual decision? Neither hospitals nor the government can force people to eat right or live healthy (although some would love to try).

The social case is certainly something that society should be talking about. Hospitals, especially those that are non-profit status, have a very deep and meaningful societal purpose and human mission that goes beyond making money. That’s one reason the “business case” for Lean has to include more than hard dollars.

That said, the expression “no margin, no mission” does apply, as a hospital or health system that doesn’t have positive cash flow won’t be around to serve patients forever.

I guess I wasn’t clear – when I said “if we were to get it right and live healthier lives” I meant “we” as society (the aggregate of lots of individual decisions), not the institutions or those of us focused on reforming healthcare. Certainly not suggesting that healthcare institutions could force that.

Comments are closed.