Some of the best lessons I have ever learned for my career are from Donald Wheeler's brilliant book Understanding Variation: The Key to Managing Chaos. One idea is that data without context is meaningless. The other is the application of statistical process control (SPC) to management decision making.

In one hospital a while back, I saw they had some performance measures posted in the lobby for the public to see. That's a good example of transparency and the attempt (or the thought) should be applauded. Unfortunately, the data likely didn't have any meaning to the general public (or to hospital employees, I would imagine).

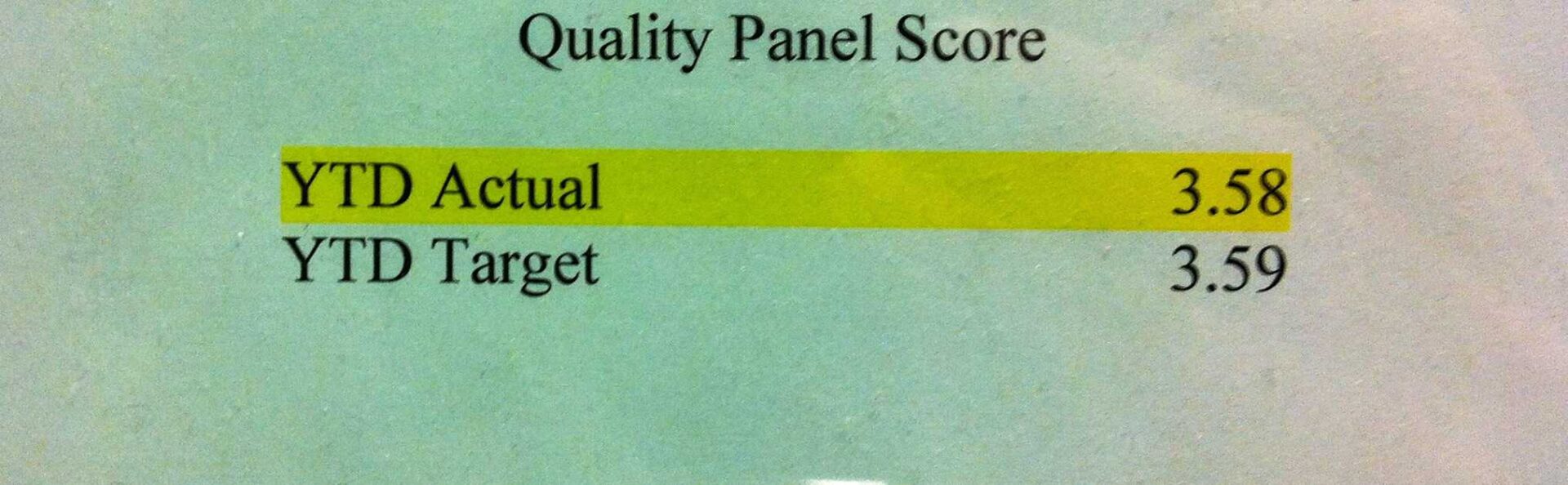

The one piece of data (and the chart) that stood out in particular:

So what do those numbers mean to the general public?

What context is missing?

- What is a “quality panel?” Is this like American Idol?

- What's the maximum (best) score? Out of 5 or out of 10?

- What is the trend over the past few years (not just comparing actual to “target”)?

- How does this score compare to other hospitals? Is 3.58 a good score or a bad score?

- This score is indicative of what risks to patients?

I'd also ask, why was the “target” set as 3.59? Did they plan to have less than perfect quality (whatever perfect would be)? Why is the actual so suspiciously close to the target? Are people gaming the numbers? Why do they even need a target? Would the lack of a target hamper people's efforts at delivering the best patient care? How does the target help improve quality? If the target were 4.5, would the actual be 4.49?

Is the hospital really helping or informing anybody through the posting of these numbers?

It would be much more helpful to plot this quality panel in a run chart or a proper SPC chart (as talked about in this post). Having some context about how this score compares to other hospitals would help (although our goal should be perfect quality, not beating benchmarks or targets).

The second primary lesson from Wheeler and SPC is that managers need to avoid overreacting to every little up and down in the data shown in a run chart or an SPC chart. If you're reacting to noise (aka “common cause variation”) and looking for simple answers to the question of “why were laboratory turnaround times longer than average yesterday?” you might be wasting a lot of time.

There was an insightful letter to the editor in the Globe & Mail paper here in Canada where I am visiting this week (see “Put on a happy face” on this page).

In part:

Every time there's a precipitous dip in the markets, you use a photo of a guy cradling his head in his hands, as if the world were coming to an end. It's tiresome, and points to a trope in the news industry that you and your readers buy into, that one or two bad days in the market is some kind of monetary natural disaster. It isn't; it's cyclical.

Great point. Not every single day downturn in the stock markets is indicative of any major event or major trend. Sometimes there is noise in the system. Up 200 points, down 200 points. No need to celebrate or get depressed with every up and down in the data. I wonder how many investors use SPC in making investment decisions, to help separate signal from noise?

If the hospital in the first example plotted their monthly quality panel score, they would do well to not overreact to every small blip up and down in that chart.

Please scroll down (or click) to post a comment. Connect with me on LinkedIn.

Let’s work together to build a culture of continuous improvement and psychological safety. If you're a leader looking to create lasting change—not just projects—I help organizations:

- Engage people at all levels in sustainable improvement

- Shift from fear of mistakes to learning from them

- Apply Lean thinking in practical, people-centered ways

Interested in coaching or a keynote talk? Let’s start a conversation.

Mark:

This reminded me of a friend’s father who worked for one of the major rail lines for his entire career.

He drafted only three memos for his superiors: one explaining why they were below targets; one explaining why they were on target; and one explaining why they were exceeding targets.

In a conversation with him he told me that he sent the very same memos (with the appropriate numbers entered) for his entire 30-year career.

Deming called it “meddling”, to react to ups and downs without knowledge. You can’t use SPC with the stock market because all the ups and downs are caused by meddling. It is not a stable system, nor is it in control. The values represented by the Dow are just someone’s “valuations”. They bear little basis to actual monetary value. How can a blue chip be worth 20% less one day versus the next? Nothing has changed 20% except perception. Now, in bulk, there might be enough meddling such that it cancels itself out over the long run, but trying to explain any variations day to day in that chaos is futile.

I think the term Deming used most often was “tampering.”

There might be some stocks that so have a trading range that’s in statistical control for some period? You’re right that statistical control (a stable system?) would be a requirement for using SPC in investing. But that sounds like the sort of “trading” that is done based on people just analyzing charts instead of truly investing based on knowing something about a company.

Excellent post! I could not agree with you more. All to often organizations will post metrics without context. I teach a statistics course at a local college and always advise students that charts must be self explanatory. Far to often data gets left in conference rooms or displayed without context. The data and charts must speak for themselves. Great post!

Mark,

Excellent points. Among other things, lean performance metrics must be able to pass the simple, “So what?” test. Without context (and with that trends – apparently missing from the example), relevance, and actionability, it’s just wallpaper. Sometimes it’s dangerous wallpaper.

Mark, I think this is a vital point. I hate the phrase “In God we trust, all others bring data” because it basically assumes that data is inherently good. Data is not king. Meaning is king.

Very recently I was coaching a team on their daily performance management meeting that had a wall-full of data. But all of it was highly variable absolute numbers. In the end, it told you nothing. I ever heard people say “it feels like there is a trend here” but they couldn’t tell because the numbers they were using were useless.

How we decide to measure something doesn’t reflect how it is, it reflect how we think. We can also use data to help us draw conclusions within our current framework of understanding, but it doesn’t often help us CHANGE that framework.

I was back at this hospital again and the metrics board is no longer on display in the lobby.

So they’ve gone from a confusing display to no display at all…

[…] where data was displayed or used “without context” as Wheeler […]

[…] Mark Graban of LeanBlog.org, where I started guest blogging long ago, writes Data without context isn’t very helpful. I love this because people think data is king, but it’s not. It’s meaning that is […]