As I'm reading the new book by Eric Ries, The Lean Startup: How Today's Entrepreneurs Use Continuous Innovation to Create Radically Successful Businesses, I'm reading it with an eye for concepts that can be applied more broadly than traditional startup settings.

There's a segment on page 21 (readable via Google Books) that talks about driving a car versus launching a rocket ship. Ries writes that driving a car includes a feedback loop between the driver and the steering wheel that's “so automatic that we often don't think about it.”

Is starting a planning a Lean program for your organization more like driving a car or launching a rocket?

Ries continues with his car analogy in writing that “if I asked you to close your eyes and write down exactly how to get to your office… you'd find it impossible. The choreography of driving is incredibly complex when one slows down to think about it.”

In describing rocket launching (and Lean is decidedly NOT rocket science), Ries writes that a rocket ship requires precise planning and calibration, that “it must be launched with the most precise instructions on what to do: every thrust, every firing of a booster, and every change in direction.” He adds that the tiniest error at launch can lead to catastrophic results.

In a thought that could maybe apply to an organization's planning for the launch of a formal Lean program, Ries adds:

“Unfortunately, too many startup business plans look more like they are planning to launch a rocket ship than drive a car,” including too much “excruciating detail” and too many assumptions.”

I've seen many organizations that want to be able to plan a 3-year or 5-year “Lean journey” in such excruciating detail, as if the perfect plan (often lifted from another organization's Lean history) will prevent error or the risk of failure. Following from the idea in Mike Rother's book Toyota Kata: Managing People for Improvement, Adaptiveness and Superior Results. Rother writes that organizations need to be “adaptive” in their approach, realizing that we can't have or know a precise plan to get from where we are to where we want to be.

Similarly, Ries argues that a startup needs to be like driving a car. You “always have a clear idea of where you're going” and you “don't give up because there's a detour in the road or you made a wrong turn. You remain thoroughly focused on getting to your destination.”

So it seems neither Ries nor Rother are saying “just wing it” or “don't have a vision.” I think they're in agreement that you can't plan every detail in advance like the launch of a rocket ship. We need to be adaptive and flexible. We need to persevere. Maybe time spent learning to be adaptive and resilient is better than time spent planning the perfect plan since that plan will necessarily change as we go?

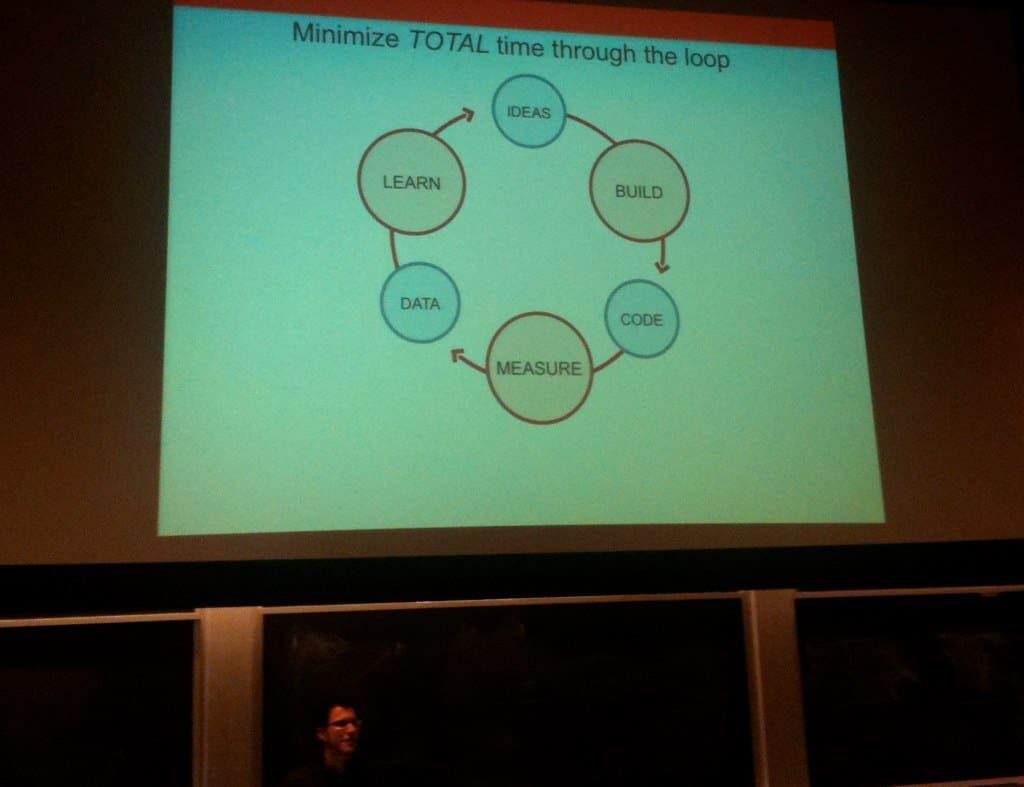

Can a hospital, at the start of a Lean journey starting today, really predict the external factors that will change in the next 3 to 5 years? Can they predict what adjustments they'll need to make in their Lean journey? Ries says, “Build – Measure – Learn” (as a loop similar to PDCA/PDSA) – see this photo I took at his MIT talk in late 2009.

Maybe Lean journeys need to be seen in a similar loop. You start somewhere. You measure progress and gauge what works well and what doesn't. You Learn. You apply those learnings to your previous steps and you incorporate those learnings into your path forward in other departments and value streams.

What do you think?

Please scroll down (or click) to post a comment. Connect with me on LinkedIn.

If you’re working to build a culture where people feel safe to speak up, solve problems, and improve every day, I’d be glad to help. Let’s talk about how to strengthen Psychological Safety and Continuous Improvement in your organization.

Nice comments Mark.

I am total agreement with you and have recently seen in a LinkedIn thread where someone suggested using the A in PDCA as Adapt vs. Act. I thought that was interesting.

I prefer to draw a big PDCA loop and than have a staircase in the middle with each step being a small PDCA loop. That serves for a better analogy for me knowing that we have an overall goal/destination but the flexibility to get there.

In a Franklin-Covey workshop once they used the analogy of an airplane. The destination was quite precise but during the journey they never were on course, always constantly adjusting. I always found that a helpful visual.

I also like the term Adapt. Anymore, I prefer PDSA – Plan, Do, Study, Adjust as the continuous improvement framework.

“Act” in PDCA sounds so certain and deterministic. “Adjust” sounds so much more adaptive and flexible.

I like the car/rocket analogy. It reminds me of a quote I heard some time ago that, to paraphrase, says if you wait for all the traffic lights to turn green, you’ll never start your trip. We need to start somewhere, because if we wait for all green lights, we’ll stay in the driveway.

The breakthrough for me in making the transition from seeing just the value stream (horizontal view, value creating processes) through the lens of lean to seeing the whole organization (horizontal and vertical) was the teaching that “a manager’s job is to practice and teach PDCA”. Simple words to live by!

Ries is telling us that the lean start-up leader’s job is to practice and teach PDCA.

And, as you observe, there couldn’t be a better framework to initiate and sustain the transformation of an organization.

I think you touched on an interesting point. So often, Lean consultants will tell clients to not let “perfect be the enemy of the good” yet agonize over trying to make a “perfect plan” for moving the organization along the journey. Liker’s new Continuous Improvement book discusses how a fully mechanistic approach to Lean doesn’t help get the results people are seeking. Workplaces are not closed systems where humans behave in an engineered way like a rocket might, so having the adapatability to be a little more organic will help in a major way.

Thanks for sharing, Brian. I’m looking forward to that new Liker book.

Mark

[…] Lean Blog: Infographic – Infographic -The Hazards of Hospitals Wow I don’t want to go to the Hospital except to help them on there needed lean journey. Automation is Not Always the Answer, in Retail or Healthcare Analogy from “The Lean Startup” for any Lean Journey? […]

[…] Analogy from “The Lean Startup” for any Lean Journey? dal Lean Blog di Mark Graban: Pianificazione lean: Guidare la macchina o lanciare un razzo nello spazio? (traduzione automatica) […]