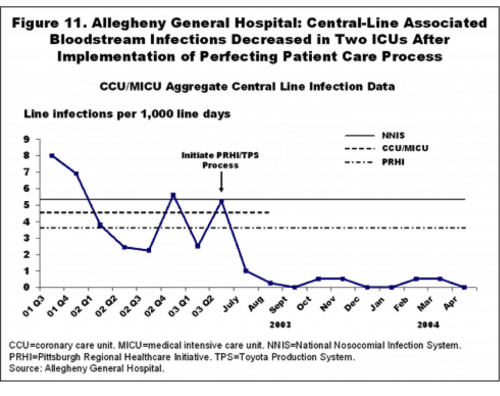

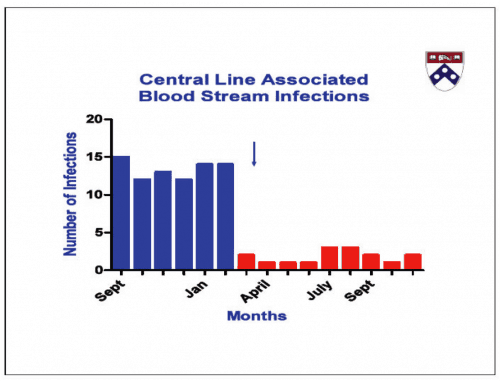

When I recently interviewed Paul O'Neill and Dr. Richard Shannon about the amazing improvements in patient safety that had been made in the Pittsburgh Regional Health Initiative organizations, they each seemed a bit frustrated that these simple, yet effective, methods for reducing hospital acquired infections (HAIs) hadn't spread more widely, more quickly. Dr. Shannon has repeated his results in Philadelphia (see the second of the two charts below, with the first being the improvements achieved when he was at Allegheny General in Pittsburgh).

This article (“Effort To End Surgeries On Wrong Patient Or Body Part Falters”) talks about how simple proven methods to reduce surgical errors aren't being adopted very widely.

Dr. Shannon was making dramatic improvements in 2002. The story has been published in journal articles, books, and DVDs. How long will it take for YOUR hospital to achieve these results? What are the barriers? Surely, they are managerial, not technical…

From the article:

What seemed pretty straightforward in 2004 now seems more complicated. “I'd argue that this really is rocket science,” said Mark Chassin, a former New York state health commissioner and since 2008 president of the Joint Commission, which has issued refinements to the 2004 directive. Chassin said he thinks such errors are growing in part because of increased time pressures. Preventing wrong-site surgery also “turns out to be more complicated to eradicate than anybody thought,” he said, because it involves changing the culture of hospitals and getting doctors — who typically prize their autonomy, resist checklists and underestimate their propensity for error — to follow standardized procedures and work in teams.

So what are we doing to change the culture? How long will it take? What still remains to be done?

Another quote from Dr. Peter Pronovost, a leader in this area:

“It's disheartening that we haven't moved the needle on this,” said Peter Pronovost, a prominent safety expert and medical director of the Johns Hopkins Center for Innovation in Quality Patient Care. “I think we made national policy with a relatively superficial understanding of the problem.” Pronovost suggests that doctors' lip service to the rules, which he calls “ritualized compliance,” may be a key factor. Studies of wrong-site errors have consistently revealed a failure by physicians to participate in a timeout.

How can we change the culture from an old automotive industry style “make the numbers” culture of a “safety culture,” like they have in aviation?

“Health care has far too little accountability for results. … All the pressures are on the side of production; that's how you get paid,” said Hopkins's Pronovost, who adds that increased pressure to turn over operating rooms quickly has trumped patient safety, increasing the chance of error.

So it's not as simple as that “stupid little checklist,” eh? Adopting the new tools without the changes in management mindsets and culture are going to get you the same results. This was true in a car factory and it's true in a hospital. So what do we do?

What do you think? Please scroll down (or click) to post a comment. Or please share the post with your thoughts on LinkedIn – and follow me or connect with me there.

Did you like this post? Make sure you don't miss a post or podcast — Subscribe to get notified about posts via email daily or weekly.

Check out my latest book, The Mistakes That Make Us: Cultivating a Culture of Learning and Innovation:

Thank you for this, Mark! I had the honor to have been “present at the creation” with Dr. Shannon in Pittsburgh, and to have written with him about the CLAB improvement for the American Journal of Medical Quality back in 2006, and then again in my first book in 2008. Dr. Shannon’s work foreshadowed Dr. Pronovost’s CLAB work in Michigan, which replicated the results across that state.

There was never a moment’s doubt that Rick Shannon’s techniques would work at Penn, too, because he relied on 1) standardizing procedures (including checklists) and educating everyone; 2) getting real-time data, not last quarter’s stale results; 3) relying on nurses as the frontline eyes and ears (he called them the “guardian angels of the central line”); and 4) giving those guardian angels the authority to stop a procedure. Dr. Shannon ushers in culture change by marshaling the forces that make people care–that is, by putting the emphasis squarely on the patient–and by giving everyone in the care chain a stake in the outcome. Staff members obsess over the data because they know that behind each number is somebody’s family member.

The checklist is woven into process change which is woven into culture change. It’s not rocket science, but you can’t pick off pieces of it, either.

Mark, it could be another essay, but there’s the sustainability business too. Dr. Shannon’s work at AGH, some said, was successful mainly because he is personally so charismatic (and because he bought Chinese lunches for the staff every week). If that were true, when he left AGH, things should have fallen apart, right? Well, the work at AGH continues to this day, at least in the pilot unit and the other units that took up the charge, with results sustaining at or near zero. And what an amazing side-effect: ICU deaths overall are down by a quarter. So while it helps to be Rick Shannon, a charismatic doc who buys food, culture change relies on the message more than the messenger.

When will these techniques take off widely across American hospitals? In the latest healthcare cliche, we seem to need a “burning platform,” meaning some deeply threatening situation (usually financial) to spur us to action. Said platform never seems to ignite because of the data at hand–you know, like 100,000 Americans who die each year from hospital-acquired infections. Does anyone smell smoke? (Maybe what we need are “burning shoes,” which will stand as my nomination for the next healthcare cliche.)

Thanks for putting these thoughts together, Mark! Great job as usual.

Thanks, Naida, for sharing your thoughts….

Readers should definitely check out Naida’s outstanding book:

The Pittsburgh Way to Efficient Healthcare: Improving Patient Care Using Toyota Base… by Naida Grunden

I see the major challenge is to get senior nursing and physician leaders on board. Most CNOs and CMOs would say their organizations have very high quality and patient safety but I bet very few could readily demonstrate it. I would also guess that efforts to improve patient satisfaction scores are consuming more of clinical management’s time and clinical support resources than reducing hospital acquired conditions.

Yeah, I think patient satisfaction is important, but not a higher priority than safety and clinical quality.

There are always plenty of reasons “why not.” Naida and Anonymous shared some of them. A fundamental issue that I’ve observed: healthcare professionals don’t acknowledge / recognize that they have a problem. To wit: a pharmacy manager recently said to me that a 1% defect rate (in a process that we were analyzing) was as good or better than all the pharmacy benchmark data that he had seen. As a result, he saw no reason for action. Note–this was a core customer service process we were working on. 1%. So many other industries have long ago abandoned the notion that 99% is an acceptable level of quality. Not so for many hospitals it seems. The education and culture change task we need to accomplish is sizable. Yet the success stories you’ve shared show it is possible–and incredibly worthwhile. (BTW I won’t get started on the risks of benchmark data.)

The training material that ValuMetrix Services that used to use (or still does?) that illustrated the fallacy of “99% quality” was insightful and powerful. So many of our everyday systems (like the power grid and mail service) have reliability so much higher than 99%.

Paul O’Neill said, in our podcast, the thing that’s lacking is leadership. It takes real leadership to set the bar higher than “being as good as everyone else.”

I hate to think that sort of leadership is really that rare…

[…] poco publicaba Mark Graban los datos de las impresionantes mejoras logradas en la “Pittsburgh Regional Health Initiative […]